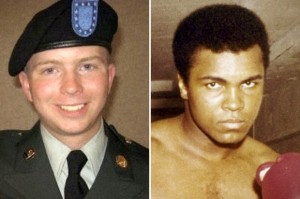

What’s in a Name? Chelsea Manning and Muhammad Ali

SPECIAL FEATURE, 26 Aug 2013

Almost 50 years ago, another big-name newsmaker shocked America with a new identity that challenged our prejudices.

Consider a polarizing political and cultural figure who is seen by many people as a hero and by others as a traitor – and who has a powerful symbolic importance to members of a persecuted minority. This person adopts a new name and a new identity, which transforms his or her relationship to mainstream culture and confuses both the media and many members of the public. Many people refuse to accept the new name and identity, or treat it as a nickname or a passing fad. At age 25, this person is prosecuted for an act of conscience-driven defiance against America’s war machine, one that arguably serves as a political turning point but also strikes many people as an unpatriotic or treasonous betrayal.

Obviously I’m talking about Chelsea Manning, at least in part. The Army leaker and whistle-blower, who was recently convicted on 17 charges of espionage and theft, declared this week that she identifies as female and no longer wants to be known as Bradley. It’s an event that feels, at this early stage, like a cultural touchstone of our young century. Among other things, as my colleagues Katie McDonough and Mary Elizabeth Williams have addressed, Manning’s “Today” show statement opened up an epistemological and taxonomical can of worms in the mainstream media, which seemed startlingly unprepared to deal with the identity preference of a high-profile transgender person.

For members of the general public to feel confused about the identity issues raised by Manning’s case, and to struggle with the question of how we decide what gender someone is – is it a matter of self-definition, of a legal piece of paper, of genetics or of physical anatomy? – is not especially surprising. That kind of confusion might even be productive, were it dealt with honestly and without hateful or dismissive rhetoric. But this is by no means a new issue for LGBT activists or media professionals; the gender transition of “Matrix” co-director Lana Wachowski (formerly Larry) was handled with far more grace last year. On the Manning story, major news outlets have appeared unsure whether to lead or follow. Most have continued to refer to Manning as a man named Bradley, although the Guardian, the Daily Mail, MSNBC, Rolling Stone, Slate, the Huffington Post and Salon were among the prominent exceptions. The current Wikipedia page is temporarily locked as “Chelsea Manning,” but was apparently changed back and forth five times within a three-hour period on Thursday. Debate continues to rage on the associated Talk page while a seven-day survey in search of consensus progresses. (Seriously, someone needs to preserve that conversation as a key historical document of 2013.)

But everything I said in that first paragraph applies not just to Manning but also to Muhammad Ali, who shocked the nation by claiming a new name and a new identity almost 50 years ago and went on, like Manning, to become an important figure in the domestic resistance to American militarism. After knocking out Sonny Liston and winning the heavyweight championship in February of 1964, the boxer until then known as Cassius Clay announced that he was a Black Muslim who was rejecting his “slave name” for a true one issued by Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam. That’s certainly not the same thing as a person who has previously lived as a man proclaiming that she’s a woman, but in the context of that time, it may have been even more startling.

Ali was stripped of one of his two heavyweight titles, on some outrageous pretext, and barred from boxing in numerous states. Most mainstream reporters and TV commentators openly mocked his new name, treating it as a bizarre affectation or, at best, adding it as an “aka” in parentheses. Many continued to refer to him as Cassius Clay into the 1970s. (One early adopter was Howard Cosell of ABC Sports, who parlayed his combative friendship with Ali into a long broadcasting career.) In Bill Siegel’s bracing new documentary “The Trials of Muhammad Ali,” Robert Lipsyte of the New York Times says his editors decreed that since Ali had become famous under his given name, that had to remain his name indefinitely. That’s exactly the same style-book rationale the Times invoked this week for continuing to call Manning “Bradley.”

I can already hear the Internet howling that it’s outrageous to compare a transgender Army private who leaked classified documents to a beloved star athlete. With the freshness and urgency of unexplored history, Siegel’s film allows us to set aside the goggles through which we view Muhammad Ali today, and see that the social forces that have pilloried and demonized Chelsea Manning in 2013 – not just flag-waving right-wingers, but mainstream politicians and pundits — did exactly the same thing to Ali in the 1960s.

It’s hard to imagine two more different individuals, at least on the surface: On one hand, the loquacious, extroverted star athlete who became the suave, trash-talking ideal of African-American masculinity; on the other, a shy and diminutive white kid from rural Oklahoma, gifted at science and computers, who evidently felt uncomfortable raised as a boy. (We need to be cautious in making assertions about Manning’s personality; she’s had little opportunity, either as Bradley or as Chelsea, to speak for herself.) But if we go a little deeper, some of the parallels between Manning and Ali, and maybe some of the differences too, are instructive. Both were talented and intelligent young people with limited formal education who grew up to be iconoclastic and enormously courageous adults, willing to make unpopular choices and face the consequences.

“The Trials of Muhammad Ali” reminds us that the Ali of the 1960s – a brash, handsome loudmouth who hung around with black radicals — has largely been lost to us through a kind of ex post facto beatification. Mostly silenced and immobilized by Parkinson’s disease in his later life, Ali has become seen as a kind of secular national saint. It wasn’t always that way. In a hard-hitting opening sequence, Siegel first shows us Ali being excoriated on television by talk-show host David Susskind, who was generally considered a liberal. This would have been after Ali’s 1967 conviction for refusing the draft (subsequently overturned by the Supreme Court on technical grounds), which was seen as spreading dangerous and un-American ideas in the black community. Susskind berates Ali as a fool, a traitor and a disgrace to his country and his race. Then we see the latter-day Ali of 2005 at the White House, receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush. I’m not saying that any such transformation is remotely likely for Chelsea Manning, but it’s entirely plausible that posterity will view her story differently than we do now.

There have been several memorable documentaries about Ali’s life and boxing career, including Leon Gast’s Oscar-winning “When We Were Kings” and the mid-‘90s TV movie “Muhammad Ali: The Whole Story,” which runs almost six hours in its home-video version. But Siegel, who co-directed the excellent historical documentary “The Weather Underground” (an Oscar nominee in 2004), draws on all kinds of file footage and illuminating interviews to reclaim Ali as an incendiary political figure and a social lightning rod. In exploring what drew Ali to the Nation of Islam, how he negotiated the split between Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X, and what led him to refuse military induction – instead of, say, taking a cushy job in the reserves or the National Guard, as athletes and entertainers often did — Siegel sheds fascinating new light on one of the most elusive and complicated public figures of the 20th century. Anyone who wants to understand what happened to America during those turbulent years needs to see this film, at least as much as they need to see “Lee Daniels’ The Butler.” And watching this story about how Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali, in the same week when Bradley Manning became Chelsea, strikes me as one of those cosmic coincidences that can’t be ignored.

After winning a gold medal at the 1960 Rome Olympics, Cassius Clay had a clear opportunity to become an all-American hero in the mold of Joe Louis. By the time he beat Liston – still one of the biggest upsets in sports history – it was clear that he had chosen a different path. Reporters and boxing insiders understood that Clay had already become a member of the Nation of Islam, but promoters did their best to squelch the story. They convinced him not to adopt a Muslim name and to stay away from Malcolm X, then the Nation’s leading intellectual, until the fight was over. Much of the pre-fight coverage was infused with a barely concealed racial anxiety. Liston had long been depicted in the mainstream press as a thuggish, fearsome ex-con – “the big Negro in every white man’s hallway,” as James Baldwin put it. But Clay’s brash, motor-mouth intelligence, and his association with what was often described as a “white-hate group,” suddenly seemed far more dangerous.

So if Cassius Clay was not quite the Bradley Manning of 1964, he was already a divisive figure who pushed a lot of white people’s buttons, well before he “came out” as a Black Muslim. The uproar that followed that announcement, as we see in Siegel’s film, had much of the same consternation, bewilderment and doublespeak we saw this week around Manning. In both cases, many people seemed to feel personally insulted or attacked by this shift of names and identities, although the reasons why are not immediately apparent. It costs us almost nothing to address another person by the name (or the gender) he or she has chosen, and can be viewed as no more than common courtesy. Do we really believe that anyone would make such a major life decision frivolously?

Then as now, some people have tried to insist on legal documents or court orders as the basis for how we name someone. In the film, Lipsyte notes that nobody ever demanded those technicalities from John Wayne, whose legal name from birth to death was Marion Morrison. But John Wayne and Tom Cruise and Snoop Dogg and all the other manufactured showbiz identities carry no hint of political or cultural rebuke. They don’t threaten ingrained and unquestioned ideas about race and gender and the immutable nature of identity quite the way that Muhammad Ali and Chelsea Manning do. We only ask the question “Does that person have the right to call themselves any damn thing they want?” when the answer makes us uncomfortable.

A man who rejects his birth name as a poisonous remnant of slavery might also refuse to fight an overseas war against a people who, as Ali observed, had never hurled racial slurs at him. A person who releases secret documents exposing American war crimes, and is willing to go to prison for it, might also claim the right to live openly under a new name and her true gender identity, and expect us to respect that choice. One of those rebels we have not merely forgiven for his declaration of freedom and his acts of resistance, but chosen to honor and venerate. The other one faces a long and lonely wait. Chelsea, we will not forget.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.