A Countryside of Concentration Camps: Burma Could Be the Site of the World’s Next Genocide

ASIA--PACIFIC, 27 Jan 2014

On November 19, 2012, Barack Obama visited Burma to keep a promise he made in 2009 to tyrants everywhere.

The promise: Stop being so tyrannical, and we’ll make it worth your while. “To those who cling to power through corruption and deceit and the silencing of dissent,” he said in his inaugural address, speaking to the Burmese military junta all but directly, “know that you are on the wrong side of history, but that we will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist.” Burma’s generals held up their side of things starting in 2010, by preparing for elections, freeing political prisoners, and relaxing controls on speech. Until then, Burma might have merited a spot on a junior varsity Axis of Evil, alongside such fellow totalitarian states as Cuba and Belarus. But in his address at Rangoon University, when the jackboot prints still hadn’t faded from the faces of the political prisoners, Obama said Burma’s “remarkable journey” toward freedom was on the right track, and he pledged U.S. support and money if reform continued.

In Obama’s heaps of praise for Burma, he buried a brief note of concern, expressed in the mildest language. In the months before his visit, riots in Arakan (also known as Rakhine), a poor coastal state on the border with Bangladesh, had killed 167 people and displaced nearly 100,000. Most of them were Rohingya Muslims, driven from their homes by Buddhist mobs. “There is no excuse for violence against innocent people,” Obama said. “And the Rohingya hold within themselves the same dignity as you do.” He praised diversity as a cardinal virtue of the United States and urged Burma to embrace its minorities. But he mentioned the Rohingya by name only once before returning, sunnily, to the subject of reform and Burma’s “potential to inspire” other formerly oppressed countries. Nice place, he said in effect, except for the attempted genocide.

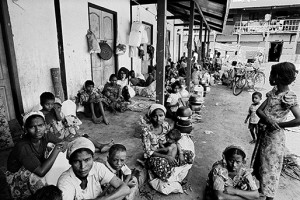

Photograph by Greg Constantine

A few displaced Rohingya set up a bike-repair stand for their fellow camp dwellers.

A year later on the streets of Rangoon, Burma’s Great Unclenching is a beautiful thing. The Burma I first visited in 1998 was a snakepit of secret police and muzzled dissent. But last fall, I heard people openly express love for the leader of Burma’s democratic opposition, Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. On every street corner, kiosks sold dozens of vibrant tabloids free from routine censorship. Burma’s economic isolation once forced foreign visitors to pack in bundles of crisp hundred-dollar bills. Now brand-new ATMs disgorge money just like in Paris or Buenos Aires.

But Arakan state looked a lot better when things were still clenched. Muslims and Buddhists who recently lived with each other peacefully now squat on opposite sides of barbed-wire fences and plot each other’s elimination. Old women and children too infirm to run from raiding parties have been speared or beaten to death in their homes. The fortunate ones are fleeing to other countries on overladen, leaky boats. In Sittway, the state capital, Buddhists have surrounded the old Muslim quarter, starving its residents into submission. “It’s a concentration camp,” a diplomat in Rangoon told me.

The U.S. government has sent diplomats to monitor Arakan, and at key junctures in the blossoming of bilateral relations, Obama has brought up the Rohingya issue. But the Rohingya are, so far, unlucky casualties of progress, and their ongoing ethnic-cleansing hasn’t been enough to sour Obama’s rapport with the Burmese president, Thein Sein. Nor, it seems, has it managed to stir the outrage of Aung San Suu Kyi, whose lack of comment has made activists, once piously reverent, now treat her as something between demoness and fool.

With Suu Kyi silent, and the international community collectively golf-clapping as Burma edges toward freedom, the Rohingya are nearly friendless in their displaced-person camps and grim ghettos, with few real champions other than a handful of Muslim countries (Saudi Arabia, Malaysia) not known for their capacity to deal with humanitarian crises. Obama closed his Rangoon speech on what he no doubt meant as a cheery note: “I stand here with confidence that something is happening in this country that cannot be reversed.” Increasingly, it sounds like a prophecy of doom.

Myebon, a town about 30 miles from Sittway, had seen little action since the Japanese left in 1945. The inhabitants who didn’t grow rice worked out of fishing boats in the Bay of Bengal. They were mostly Arakanese, the local Buddhist ethnic minority. But in June 2012, things in Myebon got nasty, in a way that was replicated in dozens if not hundreds of other places around Arakan at about the same time.

Recent Burmese history has been a series of tragedies and crimes—most of them Buddhist-on-Buddhist. Nine out of ten of Burma’s 53 million people are Buddhists, including the current president and all heads of state since Burmese independence in 1947. The generals who imprisoned Aung San Suu Kyi after she won the 1989 election were Buddhists, and the Burmese who stand to profit from the economic opening of the country (a powerful group of military-backed businessmen known as the “cronies”) are nearly all Buddhists. The opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), is led almost entirely by Buddhists, and its willowy leader, Suu Kyi, is famously devout—almost nun-like, her associates say, in her abstemious ways (“she eats a quarter of what a normal person eats”) and observance of early morning Buddhist meditation.

But this narrative of Burma as a Buddhist country, governed by competing Buddhists, elides a bitter history of rivalry between Buddhists and Muslims. The military government had kept tight control of this conflict, or at least had kept it out of the headlines, until late May 2012 when three Muslims allegedly raped and murdered a Buddhist girl in southern Arakan. That incident became the catalyst for a series of riots that the government at first made little effort to suppress, and indeed might have encouraged. Local Buddhists said the rape was just the latest Muslim-on-Buddhist sexual attack, and official news outlets whipped up hysteria by making the event a top headline—even though, statistically, it was probably not the country’s only rape that day.

The specifics of what happened next vary only slightly by account. On June 4, 2012, not long after the alleged rape, Buddhists stopped a bus and invited non-Muslims to get off. Then they let the bus go on a short distance, stopped it again, dragged approximately ten Muslim passengers onto the street, and beat them to death. After that, the violence against Muslims became organized and genocidal. Buddhists launched coordinated attacks against Muslim villages and neighborhoods all over Arakan state. Dozens of Muslims from across Arakan told me similar stories: Buddhist mobs, protected by police, showed up screaming anti-Muslim slogans and demanding that the Muslims flee. They brought guns and knives, and the Muslims who stayed behind—in some cases because they were physically unable to flee—were shot, speared, and hacked. Some of the rest made it to other countries to start their lives over, but most of the displaced are in the dozens of squalid camps across Arakan state. The penalty for leaving these camps is three months’ imprisonment—if a Rohingya is caught by the cops. If caught by the wrong civilians, it could be lynching. The Buddhists burned the Muslims’ abandoned homes and possessions to cinders. Some Muslims eventually retaliated, and a much smaller number of Buddhists died or were driven into camps of their own after riots across the state.

Arakanese Buddhists delighted in sending their Muslim neighbors away. Surprisingly, though, it appeared that Burmese Buddhists far from Arakan supported the violence just as fervently. Virtually every foreigner with extensive Burma experience I met told me a story of hearing ordinary Burmese—even friends and colleagues—speak openly about the “Bengali” problem. “We were just shocked that people we looked up to and championed, leaders of the democracy movement, turned out to be racist,” says Jennifer Quigley, executive director of the U.S. Campaign for Burma, the largest Burmese democratic activist group in the United States.

Photograph by Greg Constantine

Two members of a notoriously vicious Buddhist security force patrol a camp outside Sittway, the capital of Arakan.

And it wasn’t just pearl-clutching, I-wouldn’t-want-my-daughter-to-marry-one racism. A Burmese Buddhist who had lived in Europe for years—in places where sensitivity about human-rights issues is high and racial incitement illegal—held a dinner party not long ago, and one of the guests told me what happened when conversation turned to the Rohingya. This Burmese man knew the situation in Arakan state well and claimed to have a balanced view of the conflict. After a few drinks, he showed what “balance” looks like. He retreated to a back room, and when he returned, the conversation hushed, because he was brandishing a gigantic sword. “If any Bengali person comes to this country,” he announced, “I will cut off his head myself.”

At first, Myebon’s Buddhists tried a less confrontational way to drive their Muslims out of town: After the June riots, they just blocked the Muslims from traveling to the market, shutting off their main food supply. But some Buddhists pitied their neighbors and snuck them provisions, so the more extreme Buddhists of Myebon decided they had to try a firmer approach.

At 7 p.m., on October 23, 2012, Buddhists showed up at the edge of the town’s Muslim quarter, armed and ready to chase the residents away. “I lived side by side with Arakanese [Buddhists],” a 54-year-old teacher named U Khin Maung told me. “When they came, I was so surprised, I thought I was dreaming.” Some people resisted and others ran away. Five mosques, six madrassas, and 642 households were burned to the ground. “They left not even a cowshed standing,” U Khin Maung remembers.

At 9 a.m., the survivors ran onto a hill overlooking their former neighborhood, still in flames. The hill is small—just a few dozen feet higher than its surroundings—with a summit just big enough to fit all 4,000 of Myebon’s Muslims and give them a view of Arakanese coming from every direction, hauling big drums of gasoline.

A group of Muslims considered fighting back, but before they had a chance, favorable winds bought them time by blowing the fire back toward a Buddhist neighborhood. Even still, the Buddhists taunted them: “Come down, if you dare,” they screamed. So the Muslims of Myebon simply waited for the winds to shift back toward them and huddled with their loved ones, expecting to be burned alive.

A religious zealot holding a jerrican of gas in one hand and a lit match in the other is always and everywhere a worrisome sight, but not, of course, always and everywhere for the same reasons. Buddhists have, in some circles anyway, received a free pass from skeptics of religion, largely because of the good p.r. and fine examples of the Dalai Lama and his herbivorous Western celebrity proxies (Richard Gere, Uma Thurman). The last few years of resistance to Chinese occupation of Tibet have seen 124 self-immolations by protesting Tibetan Buddhists, and zero burnings of Chinese soldiers. By now the average American thinks that Buddhist extremists are less dangerous than Buddhist moderates (a pleasant contrast with certain well-known types of extreme Christians and Muslims) and that the most violent living Buddhist is Steven Seagal.

But violent Buddhist wack-jobbery is real—just ask the victims of Japanese fascism, which the Japanese Buddhist clergy supported rabidly—and in Burma it is flourishing. The country’s powerful clerics include a number of influential firebrands whose anti-Muslim alarmism sounds like the ranting of a saffron-robed Michele Bachmann. A Mandalay-based monk named Wirathu, the head of a Buddhist extremist movement known as “969,” appeared on a July 2013 Time magazine Asian-edition cover under the headline “THE FACE OF BUDDHIST TERROR.” “Now is the time to rise up, to make your blood boil,” Time quoted him telling his fellow Buddhists during the riots. The story called him “the Burmese Bin Laden,” a phrase that Wirathu-aligned monks I met in Rangoon seemed to think he should put on his business card.

The monks peddle implausible theories of how Muslims are slowly taking over Burmese society, by seizing land, marrying and converting women, and simply out-spawning Buddhists. The Venerable Ashinkumara, a monk in Rangoon, told me that the Muslim practice of polygamy allowed Rohingya to reproduce at astonishing speeds. (According to the United Nations Population Fund statistics, the percent of Muslim women in Burma who want another child in the next two years is actually half the percentage of Buddhist women who want another child in the same period.) He said Muslims required their Buddhist spouses to convert—this is true—and claimed that Buddhist women were changing teams at an alarming rate. And most interpretations of Islamic law prescribe death to apostates, so conversion from Buddhism is a one-way ticket. As evidence for the unidirectional nature of Islamic conquest, the Buddhists point out that, if Burma goes Muslim, it will not be the first ancient Buddhist civilization to do so. Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Afghanistan all started as Buddhist, and Bangladeshi Muslims have been persecuting the remaining Buddhists of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, just across the border from Burma, for decades.

Photograph by Greg Constantine

Thousands of displaced Rohingya lived at the unsanitary Thet Kay Pyin Zay Camp in 2012.

Most delirious with fear are the ethnically Arakanese Buddhists, who are a clear majority in Arakan state but nurse grudges like a brittle and oppressed minority. Against Muslims, they harbor the same theological and historical prejudices held by other Burmese Buddhists. But they’re also suspicious of Burma’s ethnic Burman Buddhist majority—the group that includes most of the generals and nearly all the leadership of the NLD, including Suu Kyi.

And the Arakanese don’t even need to resort to conspiracy to see ways in which the ruling party of Burma could use the Rohingya to their advantage, at Arakanese expense. One of the principal complaints of the Rohingya is that many of them have been stripped of citizenship, even those who have lived in Burma for generations. But in advance of the last election, in 2010, many Rohingya received temporary documents from the government allowing them to vote—not necessarily for the Burman-led ruling party, but certainly against the virulently anti-Muslim Arakanese parties. This drove the Arakanese nuts, and they fear that more Muslims will be allowed to vote when Burma next goes to the polls, in 2015. More generally, the Arakanese have complained that their state is a backwater, economically underdeveloped and ignored by Rangoon.

These feelings of neglect and victimhood led the Arakanese people I encountered to plead, with visible frustration, for me to see their side of things, and to agree that they—not the Muslims in camps all over the state—were the ones under attack. One was Myint Zaw, a smart young Arakanese businessman I met at a hotel in Sittway and who volunteered to be an unofficial spokesman for his people. Zaw radiated entrepreneurial zeal—he’s a contractor who works for Indian and Korean companies servicing Sittway’s deep-water ports—and I am sure that a thousand more Arakanese youngsters with his kind of energy would be enough to begin hoisting the state out of poverty.

“We are like Israel,” he told me over tea, in an attempt to explain the defensive mentality of his people: attacked on one side by Muslims and on the other by Burmans.

So far, so sane. But I never saw Zaw happier or prouder than when he told me about killing a Muslim. He did so, he said, long before it was cool. In December 2000, in a rice-trading boat off the Arakan coast, 16 Muslim pirates attacked his vessel with machetes and bows and arrows. He leaned in and brought my finger to his scalp, to feel the rough furrow of a scar from a machete. He boarded the Muslims’ boat, repelling the assault and killing one assailant.

“So you’re like Captain Jack Sparrow,” I said.

“Yes! All the Muslims ran away,” he said, beaming. “Ninety-nine percent of Muslims are thieves.”

He nevertheless said he admired their business acumen and wished his fellow Buddhists worked as hard for their people as Muslims did for theirs. He had a Muslim watchman at his business, and he said the man had torched the place last year before Buddhists cleared out the entire Muslim neighborhood next door. On his phone, he scrolled through the photos, which indeed showed the building in which we stood, reduced to its charred frame.

“Who is for the [Arakanese]?” he asked. “The Muslims have Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Al Jazeera. And we are alone.”

Homicidal intent notwithstanding, Zaw clearly believed in the factual basis of his prejudice. He loaded me into his van on the morning of the holiday of Pavaranna—the end of the three-month meditation season sometimes called “Buddhist Lent”—and drove me into Sat Roe Kya camp, for Buddhists displaced by the riots in 2012. Several aid workers urged me to see Sat Roe Kya, too, to counter the perception that foreigners don’t pay attention to the Buddhist side of the misery.

But Zaw’s tour only bolstered the case that the Muslims were more sinned against than sinning. Like all camps for displaced people, Sat Roe Kya was an unenviable home. Still, each family had its own quarters, with a water hook-up right outside. And most important, residents could enter and leave from the camp at will, without fear of arrest or attack. They could find work, and if they made enough money, they could depart Sat Roe Kya and resume their lives. But even in the camps, they had space and freedom enough for leisurely walks. On this morning, before the midday heat, Buddhists of all ages were on the roads headed to the local monastery, to say prayers for the holiday.

In Myebon, the Muslims who huddled on the hill survived only by the grace of the Burmese army, which arrived at the last moment to stop the violence. Over the next weeks and months, the Myebon Muslims moved into temporary camps and tense, terrified Rohingya neighborhoods that had somehow been spared the flames.

The Muslim ghetto in Sittway is called Aung Mingalar, and in many ways, burning it would be a mercy, since it would remove the pretense that it’s fit for habitation. Checkpoints and barbed wire keep Muslims from coming and going, except illegally or with coveted transit papers (obtainable, it’s said, for a bribe). And because no one can leave, no one can make any money from fishing or agriculture. No money means no maintenance of the buildings, now rickety and in disrepair, with nearly all the shops closed and many of the doors and windows broken or hanging crooked on their frames.

Everywhere in Aung Mingalar, men and women, young and old, accosted me with bitter tales of dispossession and violence. A man named Mohammed showed me his identification card and said he had previously worked as a driver for the Bangladeshi consulate. Now he couldn’t leave to report for duty. He needed medical treatment but feared going to Sittway Hospital to get it, because there were rumors that patients who went there tended not to return. (These rumors had basis. Soon after our conversation, the doctors at the hospital banished Muslim patients, on the grounds that Buddhists had threatened to kill them and the hospital couldn’t guarantee their safety, or that of the doctors who treated them.) A few blocks away, a woman approached me with crazy eyes, moaning about something while her brother tried to drag her away. Aung Win, a Muslim community leader, rushed to apologize for the bizarre interaction and told me the woman had seen her house razed and some of her neighbors speared. After the trauma, she hadn’t been the same.

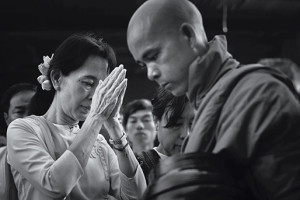

Getty

Aung San Suu Kyi won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. Now, some former admirers can’t decide if she’s a demoness or a fool.

Even a few hours in Aung Mingalar had been stifling: the heat, the misery, and the desperation all felt like they were sticking to me and the people around me, like a gritty film that would take days to wash off or forget. When I left, I passed a few armed men in uniform—they had scrutinized my permission papers on the way in—and they actually smiled and waved to me as I walked out, as if to congratulate me on leaving the area and finishing what must have been the hardest part of my day. And sure enough, the atmosphere changed as soon as I stepped past the barricades, from Muslim land to Buddhist. I immediately found a café filled with Buddhists, talking loudly while a television (playing Al Jazeera, ironically enough) droned in the background. There was not merely freedom right outside Aung Mingalar, but prosperity. I walked into a cell-phone shop that sold brand-new Samsung models more advanced than my own cherished device and for prices only a little higher than I would pay back home.

And then, a few miles down the road, I reached the next checkpoint, at a place called Bumi Junction. There the Buddhist rickshaw drivers stop, and any passenger credentialed to pass the roadblock has to walk a short distance and meet a Muslim driver on the other side. The city gives way to paddies and eventually the paddies give way to densely packed tents of displaced Rohingya. The land in other circumstances would be bucolic, with trees and water and sultry but tolerable weather. But with all these people, it reminded me less of a coconut paradise than of a Civil War–era POW camp.

The camps themselves varied widely in hygiene and sophistication. At the entrance to one that housed about 400 Rohingya, a huge public-health sign showed, via cartoons, how to deliver a baby at home without a doctor. (It warned that you should not have a man push down on your swollen belly to squirt out the baby.) The camps’ tents are constructed out of cloth, much of it reused from refugee camps built after Cyclone Nargis hit in 2008. The residents cook inside with open wood flames, risking infernos with every meal. Because of Eid Al Adha, the holiday that marks Abraham’s willingness to slit his son’s throat to appease God, the Muslims had meat, most of it donated by overseas Islamic aid agencies. The women hung thin sinews of lamb from wooden trellises that stuck up in the air above the tents, so they would dry without being spattered with mud by the naked children playing in the camp’s narrow alleys.

I met one woman, Sakina, a wispy 25-year-old mother of three who ended up there after all 230 homes in her village were burned. She stood five feet tall in dirty sandals and nervously eyed a cooking fire while we talked. When I asked how many people lived inside her tent, she had to count on her fingers to arrive at the correct number: ten. I tried to imagine all the refugees in there and felt pretty sure they’d have to sleep in shifts, or stacked on one another.

Still, Sakina said she wasn’t interested in going home; she’d prefer to pay a human-trafficker to take her far, far away—to Malaysia, perhaps, or Indonesia or southern Thailand. Nearly all the other Rohingya in the camps agreed. Not that the trip would be easy. The boats were soggy wooden dhows with unreliable engines and no life vests. Those who couldn’t afford a $100 ticket told me they’d just stow away, overloading the boats well past their maximum safe capacity, which appeared to be zero.

Just a couple weeks after I left, around 70 people trying to escape camps near Sittway drowned at sea. The tragedy surprised no one. Since the 2012 riots, dozens of vessels carrying Rohingya have capsized, killing hundreds. Others have stayed afloat but suffered motor failure, leading passengers into the gruesome predicament of having to wait to find out whether the drinking water would run out before the winds and tides pushed them to safety. And of course, being pushed to safety often means nothing more than a return to the hostile shores of their home country.

Burma’s problems—communal tension, pent-up rage against minorities—certainly existed in latent forms during the 1990s and 2000s. But during that period, the country’s democratic opposition blamed all its woes on the military dictatorship and offered the same solution to them all: Aung San Suu Kyi. Put the lady in office, and good government and ethnic harmony will follow.

Her party, the NLD, was perhaps the world’s most beloved political dissident group, and Suu Kyi a secular saint. During her nearly two decades of house arrest, Suu Kyi accrued moral credibility comparable only to Nelson Mandela, who coincidentally was released from his 27-year captivity just as Suu Kyi was put away. The government extended what amounted to a standing offer to let her leave Burma for permanent political exile, but she refused to budge from her home on Inle Lake, Rangoon, even as her two sons grew up out of her sight, and her husband, the British scholar of Buddhism Michael Aris, wasted away with cancer. With each year of confinement (which the government continued on flimsy pretexts until 2010), more Burmese came to admire her steely courage, and her international stature grew until Burmese and international human-rights activists came to view her as an almost messianic figure.

There were signs that a cult of personality was developing, but those signs were widely ignored. Mark Farmaner, the director of Burma Campaign U.K., recalls a time in 2010 when Suu Kyi called in repairmen to fix her leaky roof. At that very moment, the Burmese government was waging a war along the Thai border, and as many as 60,000 civilians had been displaced. Many were raped, killed, and mutilated. Few outsiders cared, but as soon as raindrops started leaking into Suu Kyi’s house, activists and journalists scrutinized the problem with the attention of Kremlinologists.

“When you look back on it now, the idea that someone repairing a hole on her roof would be considered a harbinger of possible political change in one of the most difficult dictatorships is laughable,” Farmaner says. “If we put out a press release about horrific human-rights abuses, no one would call us up. If we put out something about Aung San Suu Kyi, media were on the phone.”

In 2011, after the military junta transferred power to Thein Sein and Suu Kyi had emerged from house arrest, she registered the NLD as a political party under the government’s guidelines. With that one stroke, she acknowledged that the generals—the longtime captors of her and tens of thousands of other political prisoners—had the right to decide who ran the country. The move attracted muted criticism, but most Burmese still idolized her after it, and few foreigners had the time to revise and complicate their own opinions.

Now that she is free, Suu Kyi travels outside Burma frequently to accept baubles and plaques from human-rights organizations and international admirers. On those trips, activists and journalists have increasingly pressed her on the Rohingya issue. Her answers are noncommittal at best. The violence “is the result of our sufferings under a dictatorial regime,” she told a reporter in Belfast, declining to point out that the Muslims are far more oppressed. In November 2012, the BBC cornered her, and she maintained studied neutrality between the ethnic cleanser and the ethnically cleansed. “I do not think one should use one’s moral leadership, if you want to call it that, to promote a particular cause without really looking at the sources of the problems,” she said.

The most flattering possible interpretation of Suu Kyi’s silence is political expedience. She is pushing for a constitutional amendment that will restore her presidential eligibility, which she gave up by marrying a foreigner. If she is allowed to run in the 2015 elections and loses, the military-backed government will effectively get another five years of power—now with the credibility of having won an election instead of stealing it. “You have to realize that the generals are using the Rohingya issue to outmaneuver her,” a Burmese-speaking expatriate in Rangoon told me. They know that if she speaks out to defend Rohingya human rights, many Buddhists will hate her, and if she doesn’t, her old friends in Oslo might. Either way, her support will decline from its current heights. “Remember that these are people who plan military strategy for a living,” he continued.

But more and more, activists wonder whether even this interpretation gives her too much credit. “People are overanalyzing why she has been silent,” one longtime Burma activist—acquainted with Suu Kyi personally—told me. “People should be thinking about what is the most obvious reason for silence. If someone is not speaking about something like this, why might they not speak up?” He paused to let me think about this.

“Her father was a Burman Buddhist nationalist, and she’s from that background,” the activist continued. Perhaps, he said, she was simply her father’s daughter, and like most Burman Buddhists she views Burma as a Buddhist country, where Muslims and non-Burmans are merely along for the ride, like remoras sucking on the cheeks of a shark.

Since Suu Kyi’s latest BBC interview, Mark Farmaner says, people have privately told him that they now interpret her silence as simple prejudice against Muslims. “Certainly a lot of Muslims in Burma take that view,” he explained. In a statement that induced eyerolls within his organization, Suu Kyi suggested that Muslims might eventually be “integrated” into Burmese society—as if Rohingya haven’t been in Burmese society for centuries.

Suu Kyi now says that she isn’t a saint and never was. “I started out as the leader of a political party. I cannot think of anything more political than that,” she told reporters in Rangoon in December. Being “[an] icon was a depiction that was imposed on me by other people.”

In December, as part of Burma’s attempt to repair its image as a military dictatorship, it hosted the South East Asian (SEA) Games—a mini-Olympiad for the region and a showcase of the cultural dividends that openness has brought. For a few weeks, at least, people associated Burma not with ethnic violence but with chinlone, an indigenous form of hacky-sack that was included for the first time as an official SEA Games sport. All over Burma, billboards of the games’ cartoon mascot, the golden owl or zigwe, holding a torch, were posted to welcome participants. But now that the games are done, the rumor said, that torch will be used to reignite the conflict and push out the last stubborn Rohingya from Burmese soil.

The Palestinian example shows that conflicts like this can stay frozen for decades. And that may be one of the worst options of all. Those Rohingya camps, with their muddy impermanence and bored desperation, contain children and young people growing up full of resentment and grievance. The adults have few jobs, other than trafficking each other away, and they have dangerous amounts of idle time to mentally replay the stabbings of their neighbors and to plan comeuppance for Buddhists. More than one aid worker told me that the camps are fertile ground for terrorist recruitment. Wahhabism, the conservative, Saudi-backed flavor of Islam often associated with terror, is already present in Rohingya mosques. Some Arakanese assert that the Rohingya camps are lousy with Al Qaeda agents. That claim is outrageous and alarmist. But after another ten years of besiegement and subjugation, who knows?

The current priority is to avert imminent humanitarian catastrophe by keeping the communities separate and stopping angry mobs from attacking the Muslims, who are now conveniently clustered in vulnerable and flammable tents. There is little doubt that attacks would happen, if the Burmese military and police were not guarding them. But aid workers fear that, as the status quo persists, the lines between the two communities will grow indelible, and Rohingya and Buddhists will become used to living as separated, warring factions forever looking for revenge.

The two groups aren’t yet totally estranged. Buddhists still cross into the camps to sell things now and then, and everyone stands to profit if, as Obama hopes, Burma opens fully to the world and money gushes into the country the way it gushed into Thailand and Malaysia in the 1990s and 2000s. Residents of Arakan have doubts about whether the runoff from the money-geyser will trickle all the way to Sittway, or get absorbed by the cronies. But to ensure that Arakan gets its share, it will need to put aside the enmity and bloodshed of the last two years—for the sake of many more years of prosperity. Anyone who can figure out how to get Buddhists and Muslims to do that will deserve something much grander than a Nobel Peace Prize.

_____________________________

Graeme Wood is a contributing editor at The Atlantic. He traveled to Burma with support from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Center for the Prevention of Genocide.

Go to Original – newrepublic.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.