Should Twitter, Facebook and Google Executives Be the Arbiters of What We See and Read?

MEDIA, WHISTLEBLOWING - SURVEILLANCE, 25 Aug 2014

Glenn Greenwald – The Intercept

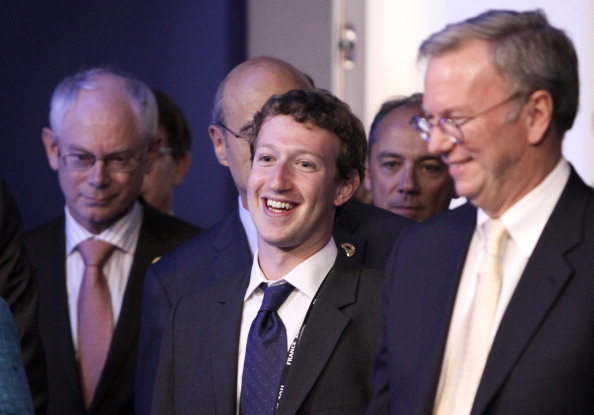

DEAUVILLE, FRANCE – MAY 26: (L-R) Herman Van Rompuy, president of the European Union, Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook Inc. and Eric Schmidt, chairman of Google Inc. arrive for the internet session of the G8 summit on May 26, 2011 in Deauville, France. (Photo by Chris Ratcliffe – Pool/Getty Images)

21 Aug 2014 – There have been increasingly vocal calls for Twitter, Facebook and other Silicon Valley corporations to more aggressively police what their users are permitted to see and read. Last month in The Washington Post, for instance, MSNBC host Ronan Farrow demanded that social media companies ban the accounts of “terrorists” who issue “direct calls” for violence.

This week, the announcement by Twitter CEO Dick Costolo that the company would prohibit the posting of the James Foley beheading video and photos from it (and suspend the accounts of anyone who links to the video) met with overwhelming approval. What made that so significant, as The Guardian‘s James Ball noted today, was that “Twitter has promoted its free speech credentials aggressively since the network’s inception.” By contrast, Facebook has long actively regulated what its users are permitted to say and read; at the end of 2013, the company reversed its prior ruling and decided that posting of beheading videos would be allowed, but only if the user did not express support for the act.

Given the savagery of the Foley video, it’s easy in isolation to cheer for its banning on Twitter. But that’s always how censorship functions: it invariably starts with the suppression of viewpoints which are so widely hated that the emotional response they produce drowns out any consideration of the principle being endorsed.

It’s tempting to support criminalization of, say, racist views as long as one focuses on one’s contempt for those views and ignores the serious dangers of vesting the state with the general power to create lists of prohibited ideas. That’s why free speech defenders such as the ACLU so often represent and defend racists and others with heinous views in free speech cases: because that’s where free speech erosions become legitimized in the first instance when endorsed or acquiesced to.

The question posed by Twitter’s announcement is not whether you think it’s a good idea for people to see the Foley video. Instead, the relevant question is whether you want Twitter, Facebook and Google executives exercising vast power over what can be seen and read.

It’s certainly true, as defenders of Twitter have already pointed out, that as a legal matter, private actors – as opposed to governments – always possess and frequently exercise the right to decide which opinions can be aired using their property. Generally speaking, the public/private dichotomy is central to any discussions of the legality or constitutionality of “censorship.”

Under the law, there’s a fundamental difference between a private individual deciding to ban all racists from entering her home and a government imprisoning people for expressing racist thoughts; the former is legitimate while the latter is not. One can, coherently, object on the one hand to all forms of state censorship, while on the other hand defending the right of private newspapers to refuse to publish certain types of Op-Eds, or the right of private blogs to ban certain types of comments, or the right of private individuals to refrain from associating with those who have certain opinions.

The First Amendment bans speech abridgments by the state, not by private actors. There’s plainly nothing illegal about Twitter, Facebook and the like suppressing whatever ideas they choose to censor.

But as a prudential matter, the private/public dichotomy is not as clean when it comes to tech giants that now control previously unthinkable amounts of global communications. There are now close to 300 million active Twitter users in the world – roughly equivalent to the entire U.S. population – and those numbers continue to grow rapidly and dramatically. At the end of 2013, Facebook boasted of 1.23 billion active users: or 1 out of every 7 human beings on the planet. YouTube, owned by Google, recently said that “the number of unique users visiting the video-sharing website every month has reached 1 billion” and “nearly one out of every two people on the Internet visits YouTube.”

These are far more than just ordinary private companies from whose services you can easily abstain if you dislike their policies. Their sheer vastness makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to avoid them, particularly for certain work. They wield power over what we know, read and see far greater than anything previously possible – or conceivable – for ordinary companies. As The Guardian‘s Ball aptly noted today in expressing concern over Twitter’s censorship announcement:

Twitter, Facebook and Google have an astonishing, alarming degree of control over what information we can see or share, whether we’re a media outlet or a regular user. We have handed them a huge degree of trust, which must be earned and re-earned on a regular basis.

It’s an imperfect analogy, but, given this extraordinary control over the means of global communication, Silicon Valley giants at this point are more akin to public utilities such as telephone companies than they are ordinary private companies when it comes to the dangers of suppressing ideas, groups and opinions. It’s not hard to understand the dangers of allowing, say, AT&T or Verizon to decree that its phone lines may not be used by certain groups or to transmit certain ideas, and the dangers of allowing tech companies to do so are similar.

In the digital age, we are nearing the point where an idea banished by Twitter, Facebook and Google all but vanishes from public discourse entirely, and that is only going to become more true as those companies grow even further. Whatever else is true, the implications of having those companies make lists of permitted and prohibited ideas are far more significant than when ordinary private companies do the same thing.

Another vital distinction is between platform and publisher. As Ball explained, companies such as Twitter have long insisted they are the former and not the latter, which means they are not responsible for what others publish on their platform (just as AT&T is not responsible for how people use its telephones). Demanding that Twitter actively intervene in what speech is and is not permissible blurs those lines, if not outright converts them into a publisher. That necessarily vests the company with far greater responsibility for determining which ideas can and cannot be aired.

If, despite these dangers, you are someone who wants Dick Costolo, Mark Zuckerberg, Eric Schmidt and the like to make lists of prohibited ideas and groups, then you really need to articulate what principles should apply. If, for instance, you want “terrorist groups” to be banned, then how is that determination made? There is intense debate all over the world about what “terrorism” means and who qualifies. Should they use the formal lists from the U.S. Government, thus empowering American officials to determine who can and cannot use social media? Should they use someone else’s lists, or make their own judgments?

If you want these companies to suppress calls for violence, as Ronan Farrow advocated, does that apply to all calls for violence, or only certain kinds? Should MSNBC personalities be allowed to use Twitter to advocate U.S. drone-bombing in Yemen and Somalia and justify the killing of innocent teenagers, or use Facebook to call on their government to initiate wars of aggression? How about Israelis who use Facebook to demand “vengeance” for the killing of 3 Israeli teenagers, spewing anti-Arab bigotry as they do it: should that be suppressed under this “no calls for violence” standard?

A Fox News host this week opined that all Muslims are like ISIS and can only be dealt with through “a bullet to the head”: should she, or anyone linking to her endorsement of violence (arguably genocide), be banned from Twitter and Facebook? How about Bob Beckel’s call on Fox that Julian Assange be “assassinated”: would that be allowed under Ronan Farrow’s no-calls-for-violence standard? I had a long dialogue with Farrow on Twitter about his op-ed but was not really able to get answers to questions like these.

None of this is theoretical. It’s the inevitable wall people run into when cheering for the suppression of speech they find “harmful.” Indeed, even as they were applauded, Twitter refused to follow their edict through to its logical conclusion when they announced they would not ban the account of the New York Post even though that tabloid featured a graphic photo of the Foley beheading on its front page, which it promoted from Twitter. The only rationale for refusing to do so is that banning the account of a newspaper because Twitter executives dislike its front page powerfully underscores how dangerous their newly announced policy is.

There are cogent reasons for opposing the spread of the Foley beheading video, but there also are all sorts of valid reasons for wanting others to see it, including a desire to highlight the brutality of this group. It’s very similar to the debate over whether newspapers should show photos of corpses from wars and other attacks: is it gratuitously graphic and disrespectful to the dead, or newsworthy and important in showing people the visceral horrors of war?

Whatever one’s views are on all of these questions, do you really want Silicon Valley executives – driven by profit motive, drawn from narrow socioeconomic and national backgrounds, shaped by homogeneous ideological views, devoted to nationalistic agendas, and collaborative with and dependent on the U.S. government in all sorts of ways – making these decisions? Perhaps you don’t want the ISIS video circulating, and that leads you to support yesterday’s decision by Twitter. But it’s quite likely you’ll object to the next decision about what should be banned, or the one after that, which is why the much more relevant question is whether you really want these companies’ managers to be making such consequential decisions about what billions of people around the world can — and cannot – see, hear, read, watch and learn.

________________________________

Glenn Greenwald is a journalist, constitutional lawyer, commentator, and author of three New York Times best-selling books on politics and law. His fifth book, No Place to Hide, about the U.S. surveillance state and his experiences reporting on the Snowden documents around the world, will be released in April 2014. Prior to his collaboration with Pierre Omidyar, Glenn’s column was featured at Guardian US and Salon. He was the debut winner, along with Amy Goodman, of the Park Center I.F. Stone Award for Independent Journalism in 2008, and also received the 2010 Online Journalism Award for his investigative work on the abusive detention conditions of Chelsea Manning. For his 2013 NSA reporting, he received the Gannett Foundation award for investigative journalism and the Gannett Foundation watchdog journalism award; the Esso Premio for Excellence in Investigative Reporting in Brazil (the first non-Brazilian to win), and the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Pioneer Award. Along with Laura Poitras, Foreign Policy magazine named him one of the top 100 Global Thinkers for 2013. He lives in Rio, Brazil.

Go to Original – firstlook.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

MEDIA:

- The Media Navigator (2025)

- Zuckerberg and Musk Have Shown that Big Tech Doesn’t Care about Facts

- BBC Middle East Editor Collaborated with CIA, Mossad

WHISTLEBLOWING - SURVEILLANCE: