Gaza: One War, One Family. Five Children, Four Dead

PALESTINE - ISRAEL, 29 Dec 2014

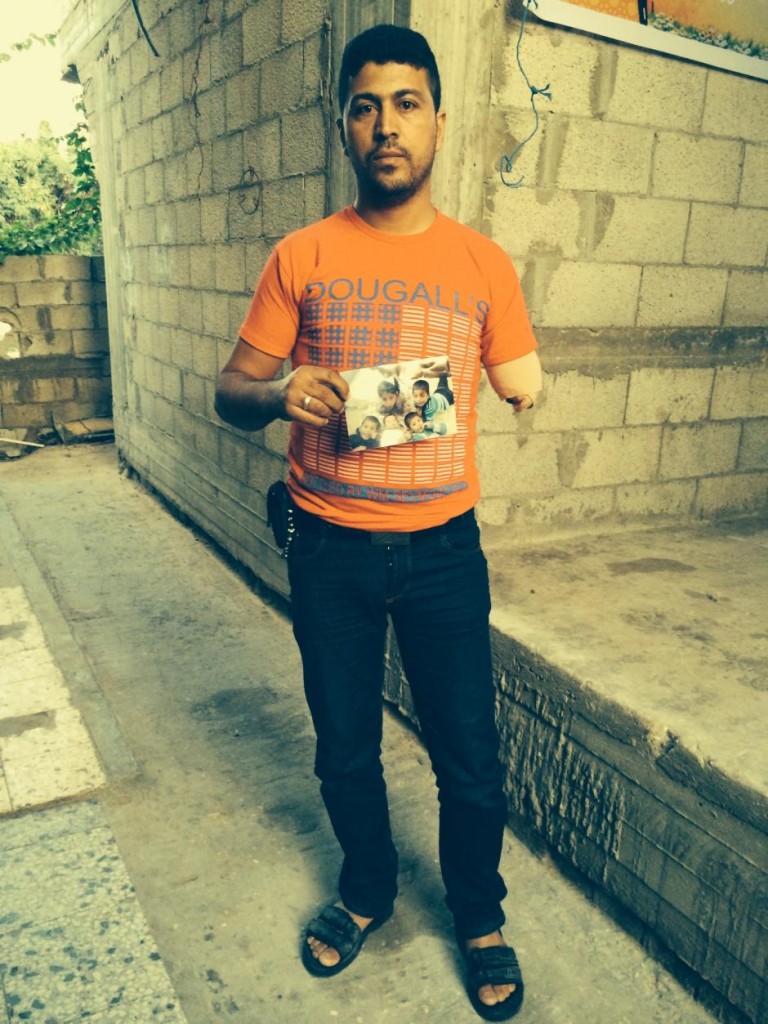

12 Dec 2014 – In a house in Rafah in southern Gaza, near the Egyptian border, Nabil Siyam, aged 34, slowly lays out pictures of his family. He only has one arm, the other was blown off by an Israeli bomb during the summer war. The pictures show his wife, Shireen, and their children – Mustafa, 9, Ghaida, a girl aged 8, Abdul Rahman, 6, Badruddin, 5 and Dalal, also a girl, aged nine months. All but Badruddin were killed by the same bomb; the little boy lost a kidney and now plays on his father’s lap. Also killed were two of Nabil’s brothers, two of his brothers’ wives and three of their children, who lived in this house.

Staring ahead with bloodshot eyes, Nabil, a vegetable farmer, says that when war broke out in July the family felt safe here. Gazans nearer the border came to this area to flee shelling where they lived. Nobody could escape into Egypt, which had closed its crossing at Rafah, and obviously it wasn’t possible to escape across the Israeli border into the line of fire. On the other side was the sea. “Everyone was trapped.”

On 21 July, Israeli rockets hit the house next door and, at 6am, Nabil and his terrified family fled. “We ran into the street, children were with mothers. We got 10 meters away when I heard a drone. I heard the sound of the bomb – it is a special sound – and looked up. The Israelis must have seen us. Drones see everything. The next thing I knew was a cloud of dust and I looked around for my children.”

Nabil picked up his phone and we were suddenly staring at scenes of the slaughter. “That was Ghaida,” says Nabil, playing the phone video over again. We looked away. He showed more photographs, including the whole family together on a beach. “It was taken here by the sea at Rafah a week before the war,” he says. By now everyone in the room is crying.

Broken Families: Nabil Siyam holds a photo of his five children, four of whom died in bombings Sarah Helm

As well as the 12 members of Nabil’s family, who died outright in the bomb, two cousins were badly injured, including 15-year-old Mohammed, who lost a leg and was transferred to a Palestinian hospital in east Jerusalem for surgery. Fighting for his life he was transferred again, this time to Turkey, so doctors could remove shrapnel from his lung. “If I die I want to come home to be buried with my family,” Mohammed told his grandfather, who accompanied him to Turkey.When he died, bringing the total number of family deaths to 13, Israel refused permission for the body to be flown into nearby Tel Aviv, so his grandfather brought Mohammed home via Jordan, then over the Allenby Bridge by ambulance, across the West Bank and Israel to Gaza’s Erez crossing and down to Rafah. It was dark when Mohammed and his grandfather reached Rafah. Immediately a fire was lit in the cemetery and the body cremated, his ashes interred near his cousins.

At least 2,200 Gazans are now known to have died in the 51-day Gaza war, which broke out on 17 July after escalating violence on both sides. Israel lost 66 soldiers in the same conflict and five Israeli civilians died, mostly from Hamas rocket fire. Among the Palestinian dead were 97 families singled out by Palestinian human rights groups because in each of these families between seven and 24 people died. The human rights groups define such families as these as totally or largely “erased”. On 17 December representatives of more than 200 countries, signatories of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which protects civilians caught up in war, are due to meet in Geneva to debate Israel’s policies in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip and in annexed East Jerusalem. The meeting has stirred controversy, as Israel argues the territories are not illegally occupied and are not covered by the Convention. The US is attempting to persuade Switzerland to call off the meeting.

The Giant Prison

I met Nabil Siyam during a week touring the 369 square kilometre strip of land, 40 kilometres long and 13 wide at its widest. I hadn’t been to Gaza since 1994, when hopes of peace were still just alive, nurtured by the Oslo accords, which envisaged a Palestinian state.

People nowadays call Gaza a giant prison, and as I saw the new perimeter wall, built since I was last here, looming through the torrential rain, I could see why. And yet Gazans on the other side are not there for committing a crime. The vast majority are descendants of Palestinians who came to Gaza 66 years ago for refuge.

Before the 1948 Arab-Israel war, which brought about the creation of Israel, many of these Gazans had lived along this coast in towns like Ashkelon, which they still call Al Madjal. During the 1948 fighting they fled to Gaza as refugees and the towns they once lived in became part of Israel.

In its early days Gaza looked more like an encampment than a prison as the refugees lived in tents, provided by UNRWA (the United Nations Relief and Works Agency) established to care for them until a permanent solution to their displacement was found. The Palestinians call the events of 1948 the nakba – catastrophe – because no solution was found and they lost their homes.

Gazan refugees now comprise 1.2 million of the 1.8 million “prisoners”. The rest have lived in Gaza for generations.Prison or not, Gaza today is certainly besieged. The walls, which run around the strip north, east and south (with the sea, patrolled by Israel, acting as a boundary to the west) were built in part to stop Palestinian suicide bombers getting out of Gaza, after a series of such murderous bombings in Israeli towns and cities, starting in the mid 1990s.

There are six crossing points into the strip, but only two are open as Egypt has recently shut Rafah again, fearing links between its own Muslim Brotherhood extremists and Hamas. Entering through the main Israeli crossing at Erez isn’t easy, not least because of the narrow turnstiles with prongs that impale and squeeze but also because permission for entry must be sought from Israel. On the day I went in, only one other – a Palestinian weighed with plastic bags – crossed through the turnstiles with me, he had received exceptional permission to visit a relative in Jerusalem hospital.

Since 1948 Gaza has always been under a siege of some sort. The best chance of freedom came with the Oslo accords. I was in Gaza when euphoria erupted at news that Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli Prime minster, and Yasser Arafat, the PLO leader, shook hands on Bill Clinton’s White House lawn in 1993. The Hamas militants’ graffiti disappeared instantly, replaced by doves of peace. Gazans’ greatest wish was to be able to travel – “to breathe”. The Israeli occupation of the strip, in force since the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, would cease. Gazans were to have a port, an airport, linking them to the rest of the world and safe passages joining the strip to the West Bank as one state, with passports for all.

This checkpoint at Erez was built at the time as an international frontier but it could always serve a dual purpose; when, in 2005, Israel withdrew its forces from Gaza, closing its settlements there, it further re-enforced control at the borders, locking Gazans in.

The intensity of the present siege dates back to 2006, when Hamas, which called for the destruction of Israel in its charter, took power inside Gaza, splitting from the PLO-led leadership in the West Bank. In an attempt to crush Hamas, Israel enforced an ever-tighter blockade. The US and most of the world refused contacts with Hamas and Gaza became a pariah – a “terrorist entity”.In April, Hamas and West Bank Palestinian leaders, under President Mahmoud Abbas, appeared reconciled. However, a new power struggle broke out just before the war and still goes on. Gaza today faces its greatest crisis since the nakba of 1948, yet the strip has no political leadership and continues to be besieged.

Gaza Underwater

Ejected from more turnstiles I was thrown by a torrent of wind and rain down an endless walkway – an open sided funnel, stretching across a no-man’s land. Ahead the other single traveller was battling forward white bags swinging wildly, as horizontal rain slashed the funnel. Emerging on the other side, Gaza seemed at first familiar rather than changed. Suddenly puddles turned to torrents and our car – a 30-year-old Mercedes – sank, with water bubbling up through the floor, though our driver drove on through.

Exceptional flooding was caused not by the storm but Israel’s bombing of several Gazan reservoirs and a pumping station near the beach. We passed the ruins. The target seems to have been a police station, also demolished, right alongside. From the shattered pumping station, raw sewage flowed out to sea. An engineer said water was being sent for tests, amid fear of cholera and other disease. Also near the beach close by were bombed out fisherman’s warehouses. Under the siege the boats can fish only three miles out or risk being shot by Israel’s patrols, but nobody was fishing in these stormy seas.

News came of evacuations to the north where floods were worst. We headed to Beit Hanoun, a badly bombed town, at the northeastern edge of the strip, passing through streets where a shop, a factory, a block of flats had been taken out. Beside a flattened mosque a tent stood where worshippers prayed. As we reached Beit Hanoun, huge piles of rubble, stretching all around, loomed in the dusk. There was no light as the power station had been bombed and electricity was rationed.

A man looks out of his shop as Palestinians walk through a flooded road following heavy rain in Gaza City November 27, 2014. Mohammed Salem/Reuters

Through the darkness white canvas flapped; boys were herding goats inside. “We used to have two farms here and many goats but they were all killed in the bombing so we have to save these last two,” says Mohammed al-Masri. “Fifteen of our family died too,” says his brother, pointing across the rubble. “Our house was five floors high. Now we sometimes sleep with the goats.”

It quickly became clear why so many civilians were killed in the summer war. Like Nabil’s family in West Rafah, these people, also near the border, couldn’t get away. In some cases Israel gave warnings, through leaflets dropped by plane or on the radio. Even then, the families often found nowhere to go. Israel accused Hamas of using children as “human shields” during the war but the whole Gazan population was a human shield. Wherever Hamas fired its rockets from, when Israel retaliated there was nowhere in this crowded land for civilians to go – no safe havens. “Civilians were at the eye of the storm,” said Raji Sourani, head of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights. Even if a family member was Hamas and carefully targeted by Israel, the house he lived in probably held as many as three families so destroying the building meant killing scores of others too.

Eye of the Storm

Gazans from Beit Hanoun fled to an UNRWA school only to be bombed again – 20 in this school were killed. Israel claimed Hamas fired rockets from the schools but UNRWA in Gaza has investigated the claims and found no evidence. It would have been impossible, say UNRWA officials, as the schools were packed to the brim with families. There were 500,000 civilians sheltering in our schools at one point and no room for rocket launchers – everyone would have known. In one school a stash of guns was found, but this was the only evidence that Hamas used schools for its operations.

In a Gaza hospital I later met a little girl who showed me her broken and scarred leg – injuries received when a bomb dropped on her school playground. Other maimed victims were gathered here too; child and adult amputees, some who had lost eyes, many badly scarred by shrapnel.

As my eyes grew accustomed to the Gaza dark, I saw more rubble mountains everywhere, then empty space, then a street of makeshift shelters banged together from corrugated iron. One of these huts had a garden path marked with old tyres leading to a gap in a tarpaulin wall. Inside a handful of logs were hissing on a wet sandy floor. Above the fire buckets, children’s clothes were strung up to dry but rain was pouring down on the clothes from a holes in the roof.

Inside lived other members of the al-Masri clan, Ahmed, Bisan and their four children. Ahmed’s parents came to Gaza as refugees in 1948. They suffered through their first winter living like this, in tents, and back then there was snow, which is also predicted this year. Like more than half of Gaza’s refugees, the family moved out of the refugee camps long ago, found work and built a house. Now the house is demolished.

A child stands by a chalkboard in a destroyed school in Gaza. Files/J.David Ake/Mohammed Abed/Afp/Getty,Amir Cohen/Reuters/Corbis

Immediately after the summer war, al-Masri and his family lived in a nearby UNRWA school, along with thousands of other homeless but it was cold and wet so he tried to build his own instead. Now he wants to move back but is not allowed. Bisan, his wife, says she is two months pregnant and getting sick. She is worried about her son Abdel Rahman, aged 13, who is “an excellent student” but now can’t study. All around are more makeshift shelters including “cartons” – small plastic living boxes – handed out by Hamas or by voluntary groups. Sandbags are piled up.

As the Israeli ground invasion began, with the aim of finding and closing off Hamas “terror tunnels” in this border area, Ashraf al-Masri was warned to leave. When he returned to his house there was no trace of it. “It was taken by the Israelis during the invasion and they blew it up before they left.”

Ashraf says his family have long since lost the deed papers of the house they fled in Israel in 1948, but he has proof of where his Gaza house was – “it is clearly shown on Google Earth”.

All across Gaza I found more rubble – areas that looked like mini Dresdens, or London during the Blitz; bombed hospitals, schools, the fledgling airport destroyed, though the latter was bombed in a previous Israeli-Gaza war. Factories were flattened too including the famous al-Awda biscuit factory, which once employed 400 workers. And all around thousands more Gazans were living in the ruins.

Life in a Carton

At UNRWA headquarters, Scott Anderson, the organisation’s deputy director in Gaza, doesn’t need Google Earth to understand the scale of the disaster: the figures marked on his white board speak for themselves. The latest count revealed 4,294 Gazan houses with major damage and uninhabitable; 5,911 with damage but still habitable and 7,058 homes totally destroyed. A total of 11,352 homes are therefore effectively destroyed and given that most Palestinian families number at least six, this means that approximately 68,162 Gazans are homeless due to the war.

Of the homeless about 23,000 are still living in UNRWA schools, four months after the end of the war. The rest are living in tents and “cartons” like those in Beit Hanoun, or in dangerous buildings, which they refuse to leave.

The challenges are clear to Mofeed el Hassina too. Hassina is one of the Palestinian technocrats who volunteered to help run Gaza after the Hamas-Fatah reconciliation fell apart. A building engineer, he now wishes he hadn’t taken the job of Minister of Public Works and Housing. He says Gaza needs 8,000 tons of cement each day to be brought in by truck, at the rate of 400 trucks a day. But first Gaza needs an army of trucks and diggers to remove 2.5 million tons of rubble.

Palestinian women walk near the ruins of houses, which witnesses said were destroyed by Israeli shelling during the most recent conflict between Israel and Hamas, in the east of Gaza City December 1, 2014. Mohammed Salem/Reuters

After the summer war there was a brief moment when such massive reconstruction seemed possible. European and American leaders declared that Gaza could not now go back to the status quo: the siege must end they said, good should come out of the horror with a new drive to find peace.

At a conference in Cairo international donors pledged more than $5.4bn to help reconstruct Gaza, but almost none of the money has been paid, and promises of new plans for lasting peace, forgotten. Instead a new “mechanism” has been devised, negotiated by the United Nations between Israel and Palestinian leaders in the West Bank. The “mechanism” is supposed to let materials in for the rebuild, but most say has simply reinforced the siege in new ways.

Israel, say Gazans, never intended that Gaza rebuild – to do so would mean Hamas would rebuild too. Cement, so badly needed for reconstruction, would have to come from Israel but might go to building new Hamas tunnels, while other materials would help Hamas rebuild its infrastructure and power-base. To prevent Hamas benefitting from the reconstruction, a mechanism was devised to control how money and materials flow. Among their demands, Israel wanted cameras in cement warehouses and precise measurements and locations for each new building, before any materials could enter the strip.

Rumours of how the mechanism works have spread fear that Israel will use the information to beef up its own intelligence on Gaza, so targets could be better identified before the next war.

The ‘Nasty Mechanism’

The UN now promises that intelligence gained from the rebuild plans will not fall into Israel’s hands but nobody believes it. By last week – four months after the end of the war – just two trucks of cement had crossed into Gaza. Hassina, the construction minister, assessed that even if 400 cement trucks were to enter Gaza every day, the rebuild would not be complete for five years “Now the siege is policed by the UN. It is absurd,” says Sami Abdel-Shafi, a leading Gazan economist.

Everyone in Gaza finds themselves entangled in the multiple prongs of what they call the “menacing mechanism”. International aid workers, seeking to improve Gazans’ shattered lives, find their own movements more restricted and their own plans for reconstruction stalled.

“We are all strangled by the mechanism too,” says one senior figure working on aid coordination. “We are all hanging on the words of Major Elrom,” says another, referring the Or Elrom, the Israeli woman major, who implements the mechanism at Erez check point. She says the mechanism will work and is the only way to deal with a “terrorist entity’ – though like most other Israelis she has never been inside Gaza herself. The major now has more power than John Kerry, the US secretary of state, and certainly more than Tony Blair, who, as middle east peace envoy for the ‘quartet group’ (the US, UN EU and Russia) has not even been to Gaza to see the damage, for security reasons. “He has no balls,” said a senior Palestinian minister. Moreover, grand ideas of peace once dreamt up by statesmen have shrivelled into a “nasty mechanism”. “Everything has to go through the Israeli window. It’s Kafka,” says Raji Sourani, the human rights activist. “It’s the Stasi,” says Avishai Margalit, professor emeritus of philosophy at Hebrew University. “It’s all about control.”

Yet there is no sign that this latest siege is weakening Hamas. The “mechanism” certainly hasn’t crushed Moussa Mohammed Abu Marzook, the senior Hamas political leader who I met in Gaza. Sitting in a 10th-floor office building, his back to a large window, he was one of the few political figures in Gaza or Jerusalem, who still professed to have ideas for peace, setting out Hamas’s new “modern agenda”. Marzook talked of a Palestinian state within its 1967 borders, saying the old Hamas character, which called for the destruction of Israel, was largely a “historical document” now.

Outside on the streets, support for Hamas has wavered amongst some who see no gains after several years of Hamas’ rule. I saw far fewer “martyrs” – posters of dead militants – pasted on walls than there were in the past. But when asked whether Hamas rockets had brought about the terrible retaliation and, hence, the suffering, Gazans all denied it. They were proud of the resistance, they said. “We have a right to resist,” many say.

Most ordinary Gazans know little of the new mechanism, and no amount of cement will bring back Nabil Siyam’s wife and children. Nabil told me he would like to try and get an artificial arm so he can start work again.

Mohammed Tilbani, owner of the bombed-out biscuit factory, smiled as he told me he had already planned how to get the factory up and running again. “It was only 80% destroyed. I’m not starting from zero,” he says.

“What we need to reconstruct most is not the buildings but the peace. We are not beggars. We are a civilised people. We don’t want charity. We don’t need $5bn. One billion would be quite enough,” says Sami Abdel Shafi.

The evening I left, I passed back by Beit Hanoun. Three young teenagers were digging in the dark. On looking closer I saw they were picking up boulders and loading them on the back of a donkey cart. They were clearing the rubble from their family orchard.

The teenagers showed me where they had planted a new clementine tree. As I squeezed back out of the Erez turnstiles, I realised why there was no longer a need to plaster up martyrs pictures on Gaza’s walls. The latest collective punishment inflicted on 1.8 million Gazans had made martyrs of them all.

Join the BDS-BOYCOTT, DIVESTMENT, SANCTIONS campaign to protest the Israeli barbaric siege of Gaza, illegal occupation of the Palestine nation’s territory, the apartheid wall, its inhuman and degrading treatment of the Palestinian people, and the more than 7,000 Palestinian men, women, elderly and children arbitrarily locked up in Israeli prisons.

DON’T BUY PRODUCTS WHOSE BARCODE STARTS WITH 729, which indicates that it is produced in Israel. DO YOUR PART! MAKE A DIFFERENCE!

7 2 9: BOYCOTT FOR JUSTICE!

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

PALESTINE - ISRAEL: