Secret Malware in European Union Attack Linked to U.S. and British Intelligence

WHISTLEBLOWING - SURVEILLANCE, 1 Dec 2014

Morgan Marquis-Boire, Claudio Guarnieri, and Ryan Gallagher – The Intercept

Complex malware known as Regin is the suspected technology behind sophisticated cyberattacks conducted by U.S. and British intelligence agencies on the European Union and a Belgian telecommunications company, according to security industry sources and technical analysis conducted by The Intercept.

Regin was found on infected internal computer systems and email servers at Belgacom, a partly state-owned Belgian phone and internet provider, following reports last year that the company was targeted in a top-secret surveillance operation carried out by British spy agency Government Communications Headquarters, industry sources told The Intercept.

The malware, which steals data from infected systems and disguises itself as legitimate Microsoft software, has also been identified on the same European Union computer systems that were targeted for surveillance by the National Security Agency.

The hacking operations against Belgacom and the European Union were first revealed last year through documents leaked by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. The specific malware used in the attacks has never been disclosed, however.

The Regin malware, whose existence was first reported by the security firm Symantec on Sunday, is among the most sophisticated ever discovered by researchers. Symantec compared Regin to Stuxnet, a state-sponsored malware program developed by the U.S. and Israel to sabotage computers at an Iranian nuclear facility. Sources familiar with internal investigations at Belgacom and the European Union have confirmed to The Intercept that the Regin malware was found on their systems after they were compromised, linking the spy tool to the secret GCHQ and NSA operations.

Ronald Prins, a security expert whose company Fox IT was hired to remove the malware from Belgacom’s networks, told The Intercept that it was “the most sophisticated malware” he had ever studied.

“Having analyzed this malware and looked at the [previously published] Snowden documents,” Prins said, “I’m convinced Regin is used by British and American intelligence services.”

A spokesman for Belgacom declined to comment specifically about the Regin revelations, but said that the company had shared “every element about the attack” with a federal prosecutor in Belgium who is conducting a criminal investigation into the intrusion. “It’s impossible for us to comment on this,” said Jan Margot, a spokesman for Belgacom. “It’s always been clear to us the malware was highly sophisticated, but ever since the clean-up this whole story belongs to the past for us.”

In a hacking mission codenamed Operation Socialist, GCHQ gained access to Belgacom’s internal systems in 2010 by targeting engineers at the company. The agency secretly installed so-called malware “implants” on the employees’ computers by sending their internet connection to a fake LinkedIn page. The malicious LinkedIn page launched a malware attack, infecting the employees’ computers and giving the spies total control of their systems, allowing GCHQ to get deep inside Belgacom’s networks to steal data.

The implants allowed GCHQ to conduct surveillance of internal Belgacom company communications and gave British spies the ability to gather data from the company’s network and customers, which include the European Commission, the European Parliament, and the European Council. The software implants used in this case were part of the suite of malware now known as Regin.

One of the keys to Regin is its stealth: To avoid detection and frustrate analysis, malware used in such operations frequently adhere to a modular design. This involves the deployment of the malware in stages, making it more difficult to analyze and mitigating certain risks of being caught.

Based on an analysis of the malware samples, Regin appears to have been developed over the course of more than a decade; The Intercept has identified traces of its components dating back as far as 2003. Regin was mentioned at a recent Hack.lu conference in Luxembourg, and Symantec’s report on Sunday said the firm had identified Regin on infected systems operated by private companies, government entities, and research institutes in countries such as Russia, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Ireland, Belgium, and Iran.

The use of hacking techniques and malware in state-sponsored espionage has been publicly documented over the last few years: China has been linked to extensive cyber espionage, and recently the Russian government was also alleged to have been behind a cyber attack on the White House. Regin further demonstrates that Western intelligence agencies are also involved in covert cyberespionage.

GCHQ declined to comment for this story. The agency issued its standard response to inquiries, saying that “it is longstanding policy that we do not comment on intelligence matters” and “all of GCHQ’s work is carried out in accordance with a strict legal and policy framework, which ensures that our activities are authorised, necessary and proportionate.”

The NSA said in a statement, “We are not going to comment on The Intercept’s speculation.”

The Intercept has obtained samples of the malware from sources in the security community and is making it available for public download in an effort to encourage further research and analysis. (To download the malware, click here. The file is encrypted; to access it on your machine use the password “infected.”) What follows is a brief technical analysis of Regin conducted by The Intercept’s computer security staff. Regin is an extremely complex, multi-faceted piece of work and this is by no means a definitive analysis.

In the coming weeks, The Intercept will publish more details about Regin and the infiltration of Belgacom as part of an investigation in partnership with Belgian and Dutch newspapers De Standaard and NRC Handelsblad.

Origin of Regin

In Nordic mythology, the name Regin is associated with a violent dwarf who is corrupted by greed. It is unclear how the Regin malware first got its name, but the name appeared for the first time on the VirusTotal website on March 9th 2011.

Der Spiegel reported that, according to Snowden documents, the computer networks of the European Union were infiltrated by the NSA in the months before the first discovery of Regin.

Industry sources familiar with the European Parliament intrusion told The Intercept that such attacks were conducted through the use of Regin and provided samples of its code. This discovery, the sources said, may have been what brought Regin to the wider attention of security vendors.

Also on March 9th 2011, Microsoft added related entries to its Malware Encyclopedia:

Alert level: Severe

First detected by definition: 1.99.894.0

Latest detected by definition: 1.173.2181.0 and higher

First detected on: Mar 09, 2011

This entry was first published on: Mar 09, 2011

This entry was updated on: Not available

Two more variants of Regin have been added to the Encyclopedia, Regin.B and Regin.C. Microsoft appears to detect the 64-bit variants of Regin as Prax.A and Prax.B. None of the Regin/Prax entries are provided with any sort of summary or technical information.

The following Regin components have been identified:

Loaders

The first stage are drivers which act as loaders for a second stage. They have an encrypted block which points to the location of the 2nd stage payload. On NTFS, that is an Extended Attribute Stream; on FAT, they use the registry to store the body. When started, this stage simply loads and executes Stage 2.

The Regin loaders that are disguised as Microsoft drivers with names such as:

serial.sys

cdaudio.sys

atdisk.sys

parclass.sys

usbclass.sys

Mimicking Microsoft drivers allows the loaders to better disguise their presence on the system and appear less suspicious to host intrusion detection systems.

Second stage loader

When launched, it cleans traces of the initial loader, loads the next part of the toolkit and monitors its execution. On failure, Stage 2 is able to disinfect the compromised device. The malware zeroes out its PE (Portable Executable, the Windows executable format) headers in memory, replacing “MZ” with its own magic marker 0xfedcbafe.

Orchestrator

This component consists of a service orchestrator working in Windows’ kernel. It initializes the core components of the architecture and loads the next parts of the malware.

Information Harvesters

This stage is composed of a service orchestrator located in user land, provided with many modules which are loaded dynamically as needed. These modules can include data collectors, a self-defense engine which detects if attempts to detect the toolkit occur, functionality for encrypted communications, network capture programs, and remote controllers of different kinds.

Stealth Implant

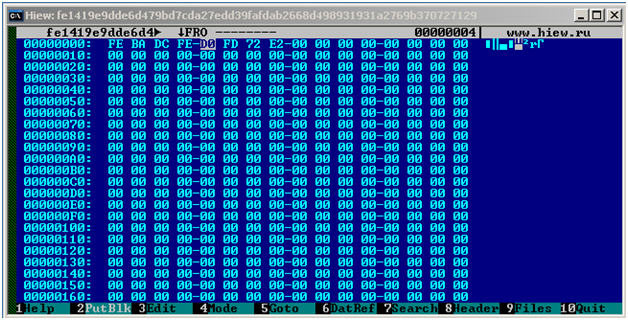

The Intercept’s investigation revealed a sample uploaded on VirusTotal on March 14th 2012 that presents the unique 0xfedcbafe header, which is a sign that it might have been loaded by a Regin driver and it appears to provide stealth functionality for the tool kit.

This picture shows the very first bytes of the sample in question, showing the unique 0xfedcbafe header at the beginning.

In order to access information stored in the computer’s memory, programs use objects that reference specific locations in memory called pointers. This binary file contains some of such pointers initialized, which corroborates the hypothesis that the file was dumped from memory during a forensic analysis of a compromised system.

The sample has the following SHA256 hash:

fe1419e9dde6d479bd7cda27edd39fafdab2668d498931931a2769b370727129

This sample gives a sense of the sophistication of the actors and the length of the precautions they have been taking in order to operate as stealthily as possible.

When a Windows kernel driver needs to allocate memory to store some type of data, it creates so called kernel pools. Such memory allocations have specific headers and tags that are used to identify the type of objects contained within the block. For example such tags could be Proc, Thrd or File, which respectively indicate that the given block would contain a process, thread or file object structure.

When performing forensic analysis of a computer’s memory, it is common to use a technique called pool scanning to parse the kernel memory, enumerate such kernel pools, identify the type of content and extract it.

Just like Regin loader drivers, this driver repeatedly uses the generic “Ddk “ tag with ExAllocatePoolWithTag() when allocating all kernel pools:

This picture shows the use of the “ddk “ tag when allocating memory with the Windows ExAllocatePoolWIthTag() function.

The generic tag which is used throughout the operating system when a proper tag is not specified. This makes it more difficult for forensic analysts to find any useful information when doing pool scanning, since all its memory allocations will mix with many generic others.

In addition, when freeing memory using ExFreePool(), the driver zeroes the content, probably to avoid leaving traces in pool memory.

The driver also contains routines to check for specific builds of the Windows kernel in use, including very old versions such as for Windows NT4 Terminal Server and Windows 2000, and then adapts its behavior accordingly.

Windows kernel drivers operate on different levels of priority, from the lowest PASSIVE_LEVEL to the highest HIGH_LEVEL. This level is used by the processor to know what service give execution priority to and to make sure that the system doesn’t try to allocate used resources which could result in a crash.

This Regin driver recurrently checks that the current IRQL (Interrupt Request Level) is set to PASSIVE_LEVEL using the KeGetCurrentIrql() function in many parts of the code, probably in order to operate as silently as possible and to prevent possible IRQL confusion. This technique is another example of the level of precaution the developers took while designing this malware framework.

Upon execution of the unload routine (located at 0xFDEFA04A), the driver performs a long sequence of steps to remove remaining traces and artifacts.

Belgacom Sample

In an interview given to the Belgian magazine MondiaalNiews, Fabrice Clément, head of security of Belgacom, said that the company first identified the attack on June 21, 2013.

In the same interview Clément says that the computers targeted by the attackers included staff workstations as well as email servers.

These statements confirm the timing and techniques used in the attack.

From previously identified Regin samples, The Intercept developed unique signatures which could identify this toolkit. A zip archive with a sample identified as Regin/Prax was found in VirusTotal, a free, online website which allows people to submit files to be scanned by several anti-virus products. The zip archive was submitted on 2013-06-21 07:58:37 UTC from Belgium, the date identified by Clément. Sources familiar with the Belgacom intrusion told The Intercept that this sample was uploaded by a systems administrator at the company, who discovered the malware and uploaded it in an attempt to research what type of malware it was.

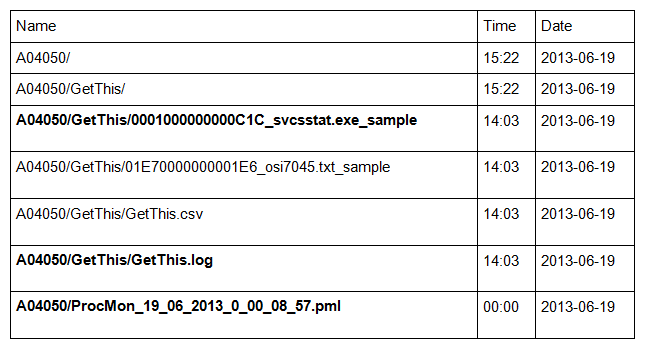

The archive contains:

Along with other files The Intercept found the output of a forensic tool, GetThis, which is being run on target systems looking for malware. From the content of the GetThis.log file, we can see that a sample called “svcsstat.exe” and located in C:\Windows\System32\ was collected and a copy of it was stored.

The malware in question is “0001000000000C1C_svcsstat.exe_sample ”. This is a 64bit variant of the first stage Regin loader aforementioned.

The archive also contains the output of ProcMon, “Process Monitor”, a system monitoring tool distributed by Microsoft and commonly used in forensics and intrusion analysis.

This file identifies the infected system and provides a variety of interesting information about the network. For instance:

USERDNSDOMAIN=BGC.NET

USERDOMAIN=BELGACOM

USERNAME=id051897a

USERPROFILE=C:\Users\id051897a

The following environment variable shows that the system was provided with a Microsoft SQL server and a Microsoft Exchange server, indicating that it might one of the compromised corporate mail server Fabrice Clément mentioned to Mondiaal News:

Path=C:\Program Files\Legato\nsr\bin;C:\Windows\system32;C:\Windows;C:\Windows\System32\Wbem;C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\;C:\Program Files\Microsoft Network Monitor 3\;C:\Program Files\System Center Operations Manager 2007\;c:\Program Files (x86)\Microsoft SQL Server\90\Tools\binn\;D:\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\bin

Below is a list of hashes for the files The Intercept is making available for download. Given that that it has been over a year since the Belgacom operation was publicly outed, The Intercept considers it likely that the GCHQ/NSA has replaced their toolkit and no current operations will be affected by the publication of these samples.

Regin Samples

32-bit Loaders

20831e820af5f41353b5afab659f2ad42ec6df5d9692448872f3ed8bbb40ab92

7553d4a5914af58b23a9e0ce6a262cd230ed8bb2c30da3d42d26b295f9144ab7

f89549fc84a8d0f8617841c6aa4bb1678ea2b6081c1f7f74ab1aebd4db4176e4

fd92fd7d0f925ccc0b4cbb6b402e8b99b64fa6a4636d985d78e5507bd4cfecef

225e9596de85ca7b1025d6e444f6a01aa6507feef213f4d2e20da9e7d5d8e430

9cd5127ef31da0e8a4e36292f2af5a9ec1de3b294da367d7c05786fe2d5de44f

b12c7d57507286bbbe36d7acf9b34c22c96606ffd904e3c23008399a4a50c047

f1d903251db466d35533c28e3c032b7212aa43c8d64ddf8c5521b43031e69e1e

4e39bc95e35323ab586d740725a1c8cbcde01fe453f7c4cac7cced9a26e42cc9

a0d82c3730bc41e267711480c8009883d1412b68977ab175421eabc34e4ef355

a7493fac96345a989b1a03772444075754a2ef11daa22a7600466adc1f69a669

5001793790939009355ba841610412e0f8d60ef5461f2ea272ccf4fd4c83b823

a6603f27c42648a857b8a1cbf301ed4f0877be75627f6bbe99c0bfd9dc4adb35

8d7be9ed64811ea7986d788a75cbc4ca166702c6ff68c33873270d7c6597f5db

40c46bcab9acc0d6d235491c01a66d4c6f35d884c19c6f410901af6d1e33513b

df77132b5c192bd8d2d26b1ebb19853cf03b01d38afd5d382ce77e0d7219c18c

7d38eb24cf5644e090e45d5efa923aff0e69a600fb0ab627e8929bb485243926

a7e3ad8ea7edf1ca10b0e5b0d976675c3016e5933219f97e94900dea0d470abe

a0e3c52a2c99c39b70155a9115a6c74ea79f8a68111190faa45a8fd1e50f8880

d42300fea6eddcb2f65ffec9e179e46d87d91affad55510279ecbb0250d7fdff

5c81cf8262f9a8b0e100d2a220f7119e54edfc10c4fb906ab7848a015cd12d90

b755ed82c908d92043d4ec3723611c6c5a7c162e78ac8065eb77993447368fce

c0cf8e008fbfa0cb2c61d968057b4a077d62f64d7320769982d28107db370513

cca1850725f278587845cd19cbdf3dceb6f65790d11df950f17c5ff6beb18601

ecd7de3387b64b7dab9a7fb52e8aa65cb7ec9193f8eac6a7d79407a6a932ef69

e1ba03a10a40aab909b2ba58dcdfd378b4d264f1f4a554b669797bbb8c8ac902

392f32241cd3448c7a435935f2ff0d2cdc609dda81dd4946b1c977d25134e96e

9ddbe7e77cb5616025b92814d68adfc9c3e076dddbe29de6eb73701a172c3379

8389b0d3fb28a5f525742ca2bf80a81cf264c806f99ef684052439d6856bc7e7

32-bit Rootkit

fe1419e9dde6d479bd7cda27edd39fafdab2668d498931931a2769b370727129

32-bit Orchestrator

e420d0cf7a7983f78f5a15e6cb460e93c7603683ae6c41b27bf7f2fa34b2d935

4139149552b0322f2c5c993abccc0f0d1b38db4476189a9f9901ac0d57a656be

64-bit Loader (Belgacom)

4d6cebe37861ace885aa00046e2769b500084cc79750d2bf8c1e290a1c42aaff

______________________________

Email the authors: morgan@firstlook.org, nex@nex.sx, ryan.gallagher@theintercept.com

Go to Original – firstlook.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

WHISTLEBLOWING - SURVEILLANCE: