André Gide on Sincerity, Being vs. Appearing, and What It Really Means to Be Yourself

REVIEWS, 16 Mar 2015

Maria Popova, Brain Pickings – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Don’t ever do anything through affectation or to make people like you or through imitation or for the pleasure of contradicting.”

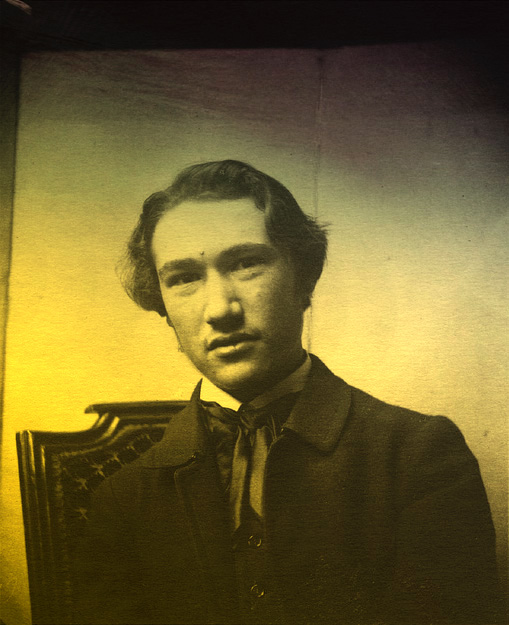

It was only at the very end of his long life that the great French author André Gide (November 22, 1869–February 19, 1951) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his “fearless love of truth and keen psychological insight.” But the seed for it was planted in his youth — Gide was among the many celebrated authors who reaped the creative and spiritual benefits of keeping a diary. In one of his earliest journal entries, he wrote: “A diary is useful during conscious, intentional, and painful spiritual evolutions. Then you want to know where you stand… An intimate diary is interesting especially when it records the awakening of ideas.”

It was only at the very end of his long life that the great French author André Gide (November 22, 1869–February 19, 1951) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his “fearless love of truth and keen psychological insight.” But the seed for it was planted in his youth — Gide was among the many celebrated authors who reaped the creative and spiritual benefits of keeping a diary. In one of his earliest journal entries, he wrote: “A diary is useful during conscious, intentional, and painful spiritual evolutions. Then you want to know where you stand… An intimate diary is interesting especially when it records the awakening of ideas.”

That remarkable journey of awakening began shortly before his twentieth birthday and continued until his death. It was eventually published as The Journals of André Gide (public library) — a treasure trove of such “keen psychological insight” so rich and enduring that young Susan Sontag found in it “perfect intellectual communion” and extolled the virtues of its frequent rereading. Sontag was not alone — Gide’s journal, while a private record of introspection, makes comprehensible and thus endurable the most elusive, complex, and difficult experiences common not only to writers, not only to all artists, but to the entire human family.

One of his most lucid and luminous such meditations deals with the paradox of sincerity, the difference between being and appearing, and the monumental question of what it really means to be oneself.

The week after his twentieth birthday, the same day he laid out his rules of moral conduct, young Gide writes:

Whenever I get ready again to write really sincere notes in this notebook, I shall have to undertake such a disentangling in my cluttered brain that, to stir up all that dust, I am waiting for a series of vast empty hours, a long cold, a convalescence, during which my constantly reawakened curiosities will lie at rest; during which my sole care will be to rediscover myself.

The conquest of sincerity would become a driving force in his life, both in his private and public writings, and twenty-year-old Gide lays its foundation under the heading RULE OF CONDUCT:

Pay no attention to appearing. Being is alone important.

And do not long, through vanity, for too hasty manifestation of one’s essence.

Whence: do not seek to be through the vain desire to appear; but rather because it is fitting to be so.

He admonishes against the most perilous manifestation of mistaking appearing for being — imitation. Catching himself emulating Stendhal, young Gide cautions — himself and, by extension, all of us, for this is the great gift of his journal:

I must stop puffing up my pride (in this notebook) just for the sake of doing as Stendhal did. The spirit of imitation; watch out for it. It is useless to do something simply because another man has done it. One must remember the rule of conduct of the great after having isolated it from the contingent facts of their lives, rather than imitating the little facts.

Dare to be yourself. I must underline that in my head too.

Don’t ever do anything through affectation or to make people like you or through imitation or for the pleasure of contradicting.

By the following summer, he is further consumed with this elusive subject of inhabiting one’s self. In an entry from August of 1891, he writes:

My mind was quibbling just now as to whether one must first be before appearing or first appear and then be what one appears. (Like the people who first buy on credit and later worry about their debt; appearing before being amounts to getting in debt toward the physical world.)

Perhaps, my mind said, we are only in so far as we appear.

Moreover the two propositions are false when separated:

- We are for the sake of appearing.

- We appear because we are.

The two must be joined in a mutual dependence. Then you get the desired imperative. One must be to appear.

The appearing must not be distinguished from the being; the being asserts itself in the appearing; the appearing is the immediate manifestation of the being.

By December, the 21-year-old writer has grown particularly concerned with the importance and difficulty of sincerity in creative work. (This paradox is something artist Carroll Dunham would capture beautifully more than a century later, in observing that “you have to make art to be an artist, but you have to be an artist to make art.” In her own magnificent journal, artist Anne Truitt also contemplated the difference between doing art and being an artist.) Gide writes:

When one has begun to write, the hardest thing is to be sincere. Essential to mull over that idea and to define artistic sincerity. Meanwhile, I hit upon this: the word must never precede the idea. Or else: the word must always be necessitated by the idea. It must be irresistible and inevitable; and the same is true of the sentence, of the whole work of art. And for the artist’s whole life, since his vocation must be irresistible…

Noting that the fear of being insincere has been “tormenting” him for several months and preventing him from writing, he sighs:

Oh, to be utterly and perfectly sincere…

Two weeks later, he returns to the subject with renewed marvel at its paradoxical nature and considers the “reverse sincerity” of the artist:

Rather than recounting his life as he has lived it, [the artist] must live his life as he will recount it. In other words, the portrait of him formed by his life must identify itself with the ideal portrait he desires. And, in still simpler terms, he must be as he wishes to be.

I am torn by a conflict between the rules of morality and the rules of sincerity.

Morality consists in substituting for the natural creature (the old Adam) a fiction that you prefer. But then you are no longer sincere. The old Adam is the sincere man.

This occurs to me: the old Adam is the poet. The new man, whom you prefer, is the artist. The artist must take the place of the poet. From the struggle between the two is born the work of art.

The Journals of André Gide is a remarkable and timelessly rewarding read in its entirety, on par with such rare masterworks as Thoreau’s journals and Rilke’s letters — the kind that lodges itself in the soul and remains there a lifetime. Complement this particular sliver with pioneering artist and female entrepreneur Wanda Gág on the two selves and young Tolstoy’s diaristic search of selfhood.

_____________________________

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors.

Go to Original – brainpickings.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.