Murder at Sea: Captured on Video, but Killers Go Free (Part 2)

SPECIAL FEATURE, 3 Aug 2015

Ian Urbina – The New York Times

Read Parts: (1 here) – (3 here) – (4 here)

A video shows at least four unarmed men being gunned down in the water. Despite dozens of witnesses, the killings went unreported and remain a mystery.

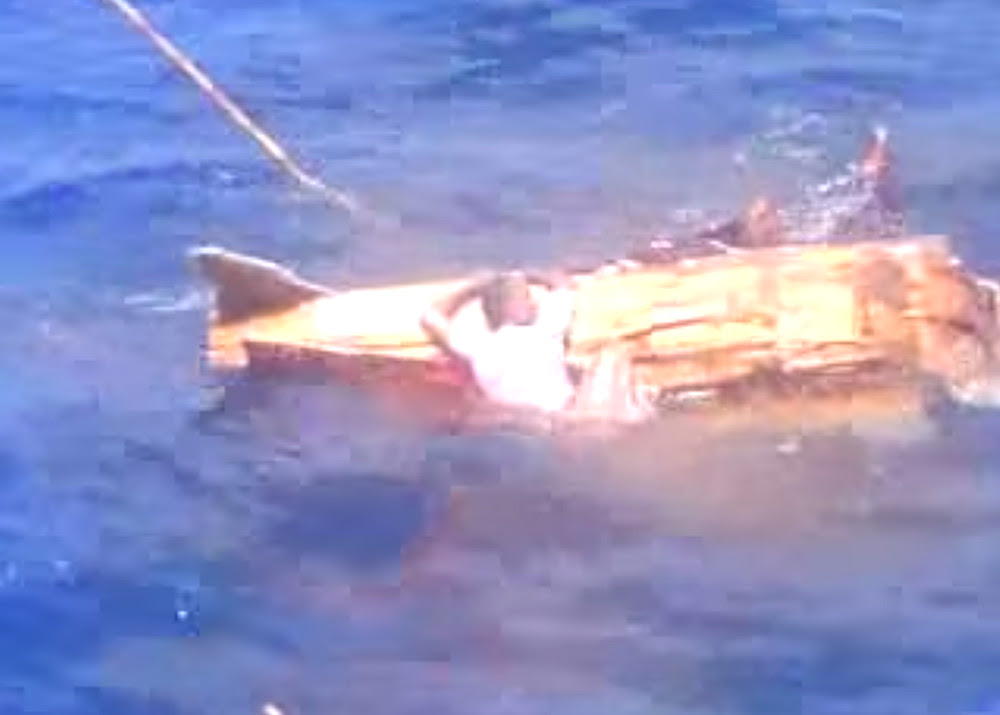

20 Jul 2015 — The man bobbing in the sea raises his arms in a seeming sign of surrender before he is shot in the head. He floats face down as his blood stains the blue water.

A slow-motion slaughter unfolds over the next 6 minutes and 58 seconds. Three other men floating in the ocean, some clinging to what looks like the wreckage of an overturned wooden boat, are surrounded by several large white tuna longliners. The sky above is clear and blue; the sea below, dark and choppy. As the ships’ engines idle loudly, at least 40 rounds are fired as the unarmed men are methodically picked off.

“Shoot, shoot, shoot!” commands a voice over one of the ship’s loudspeakers as the final man is killed. Soon after, a group of men on deck who appear to be crew members laugh among themselves, then pose for selfies.

Despite dozens of witnesses on at least four ships, those killings remain a mystery. No one even reported the incident — there is no requirement to do so under maritime law nor any clear method for mariners, who move from port to port, to volunteer what they know. Law enforcement officials learned of the deaths only after a video of the killings was found on a cellphone left in a taxi in Fiji last year, then posted on the Internet.

With no bodies, no identified victims and no exact location of where the shootings occurred, it is unclear which, if any, government will take responsibility for leading an investigation. Taiwanese fishing authorities, who based on the video connected a fishing boat from Taiwan to the scene but learned little from the captain, say they believe the dead men were part of a failed pirate attack. But maritime security experts, warning that piracy has become a convenient cover for sometimes fatal score-settling, said it is just as likely that the men were local fishermen in disputed waters, mutinied crew, castoff stowaways or thieves caught stealing fish or bait.

“Summary execution, vigilantism, overzealous defense, call it what you will,” said Klaus Luhta, a lawyer with the International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots, a seafarers’ union. “This boils down just the same to a case of murder at sea and a question of why it’s allowed to happen.”

The oceans, plied by more ships than ever before, are also more armed and dangerous than any time since World War II, naval historians say. Thousands of seamen every year are victims of violence, with hundreds killed, according to maritime security officials, insurers and naval researchers. Last year in three regions alone — the western Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia and the Gulf of Guinea off West Africa — more than 5,200 seafarers were attacked by pirates and robbers and more than 500 were taken hostage, a database built by The New York Times shows.

Many merchant vessels hired private security starting in 2008 as pirates began operating across larger expanses of the ocean, outstripping governments’ policing capacities. Guns and guards at sea are now so ubiquitous that a niche industry of floating armories has emerged. The vessels — part storage depot, part bunkhouse — are positioned in high-risk areas of international waters and house hundreds of assault rifles, small arms and ammunition. Guards on board wait, sometimes for months in decrepit conditions, for their next deployment.

Though pirate attacks on large container ships, like that depicted in the film “Captain Phillips,” have dropped sharply over the past several years, other forms of violence remain pervasive.

Armed gangs run protection rackets requiring ship captains to pay for safe passage in the Bay of Bengal near Bangladesh. Nigerian marine police officers routinely work in concert with fuel thieves, according to maritime insurance investigators. Off the coast of Somalia, United Nations officials say, some pirates who used to target bigger ships have transitioned into “security” work on board foreign and local fishing vessels, fending off armed attacks, but also firing on rivals to scare them away.

Provocations are common. Countries are racing one another to map and lay claim to untapped oil, gas or other mineral resources deep in the ocean, sparking clashes and boat burnings. From the Mediterranean to offshore Australia to the Black Sea, human traffickers carrying refugees and migrants sometimes ram competitors’ boats or deliberately sink their own ships to get rid of their illicit passengers or force a rescue.

Violence among fishing boats is widespread and getting worse. Heavily subsidized Chinese and Taiwanese vessels are aggressively expanding their reach, said Graham Southwick, the president of the Fiji Tuna Boat Owners Association. Radar advancements and the increased use of so-called fish-aggregating devices — floating objects that attract schools of fish — have heightened tensions as fishermen are more prone to crowd the same spots. “Catches shrink, tempers fray, fighting starts,” Mr. Southwick said. “Murder on these boats is relatively common.”

An employee inspected a rifle aboard the Resolution, a floating armory that anchored in the Gulf of Oman. CreditBen C. Solomon/The New York Times

The violent crime rate related to fishing boats is easily 20 times that of crimes involving tankers, cargo ships or passenger ships, said Charles N. Dragonette, who tracked seafaring attacks globally for the United States Office of Naval Intelligence until 2012. “So long as the victims were Indonesian, Malay, Vietnamese, Filipino, just not European or American, the story never resonated,” he said.

Prosecutions for crimes at sea are rare — one former United States Coast Guard official put it at “less than 1 percent” — because many ships lack insurance and captains are averse to the delays and prying that can come with a police investigation. The few military and law enforcement ships that patrol international waters are usually forbidden from boarding ships flying another country’s flag unless given permission. Witnesses willing to speak up are scarce; so is physical evidence.

Violence at sea and on land are handled differently, Mr. Dragonette said. “Ashore, no matter how brutal the repression or how corrupt the local government, someone will know who the victims are, where they were, that they did not return,” he said. “At sea, anonymity is the rule.”

The creaky wooden fishing boat strained to cut through eight-foot swells on a clear black night, as its captain, who goes only by the name Rio, spread out a regional map.

Headed north, about 50 miles from the Natuna Islands in the South China Sea, he tapped his finger on his location, widened his eyes and contorted his face to register fear. Then, he silently reached over and opened a wheelhouse compartment revealing a Glock handgun.

He had a good reason to be armed. The waters in this region, especially those near Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam, are among the most perilous in the world. More than 3,100 mariners were assaulted or kidnapped in the area last year, according to the Times database, consisting of more than 6,000 crime reports.

The database includes information provided by the Office of Naval Intelligence; two maritime security firms, OceanusLive and Risk Intelligence; and a research group called Oceans Beyond Piracy. No international agency comprehensively tracks maritime violence.

The death tolls in these attacks are murky because follow-up investigations are rare, police reports often lack details and bodies tend to disappear at sea. But maritime researchers estimated that hundreds of seafarers are killed annually in attacks. (They caution those numbers are likely to be undercounts because they do not include deaths close to shore or in some particularly dangerous areas where deaths are rarely reported to international authorities.)

Typical culprits included: rubber-skiff pirates armed with rocket-propelled grenades, night-stalking fuel thieves, hit-and-run bandits wielding machetes. But a variety of other actors appear too, and many of them are not as they initially seem: hijackers masquerading as marine police officers, human traffickers posing as fishermen, security guards moonlighting as arms dealers.

For instance, there were 10 Sri Lankan migrants, a group that included women and children, who were smuggled aboard a fishing boat in 2012 near the island nation. When their demands to set a new course for Australia were refused, the migrants attacked the crew, killing at least two men by throwing them overboard. Or the three captive Burmese workers who in 2009 escaped their Thai trawler in the South China Sea by leaping overboard, swimming to a nearby yacht, killing its owner and stealing his lifeboat.

The waters near Bangladesh illustrate why maritime violence is frequently overlooked by the international community. In the past five years, nearly 100 sailors and fishermen have been killed annually in Bangladeshi waters — and as least as many taken hostage — in a string of attacks by armed gangs, according to local media and police reports.

Weapons, tactical gear and body armor were stored in a container on the Resolution. CreditBen C. Solomon/The New York Times

Armed assaults have been a problem there for two decades, according to insurance and maritime security analysts. In 2013, the Bangladeshi media reported the abduction of more than 700 fishermen, 150 in September alone. Forty were reported killed in a single episode, many of them with their feet and hands bound before being thrown overboard.

These attacks were usually conducted by the half-dozen armed gangs that operate protection rackets in the Bay of Bengal and the swampy inland waters called the Sundarbans. Last year, they engaged in gun battles with the Bangladesh Air Force and Coast Guard during government raids on coastal camps and hostage ships.

Bangladesh’s former foreign minister, Dr. Dipu Moni, reprimanded the international shipping industry and the foreign and local news media several years ago for defaming the country by describing its waters as a “high risk” zone for piracy.

“There has not been a single incident of piracy” in years, Dr. Moni said in a December 2011 written statement, adding that most of the violence off the nation’s coast involved petty theft and robberies, most often committed by “dacoits” (a term derived from the Hindi word for bandits).

Those claims pivot on a legal distinction between piracy, which under international law occurs on the high seas or in waters farther than 12 miles from shore, and robbery, which involves attacks closer to land.

Insurance companies once charged $500 for each trip to and from the ports located in the west of India, but increased the rate to $150,000, given the area’s piracy-prone designation, a Bangladeshi foreign ministry official said during a news conference in December 2011. After Bangladeshi officials protested to the International Maritime Bureau, which tracks piracy at sea, that their country was stigmatized as a high-piracy zone, the group amended its website to say its warning covered piracy and armed robbery.

In an interview, Mukundan Pottengal, the director of the bureau, which is primarily funded by shipping companies and insurers, said his organization does not try to determine the exact location of attacks or whether they are in national or international waters, partly because these details are often contested by countries.

“Whether they are called pirates or robbers is a legal distinction,” he said. “It does not change the nature of their act or the danger to the ship or crew when armed strangers get on board their ship.”

On his fishing boat, Rio said that violence is just a part of life at sea. “You must be ready, always ready,” he said. For instance, he explained that larger, unlicensed fishing vessels in the area often plow through local fishermen’s nets, not just eliminating their catch, but destroying their livelihoods.

Making a hand gesture as though he was firing his gun in the air, Rio revved his engine, lurching the boat forward, showing how he charged at others in these situations.

A wiry chain-smoker, Rio recounted the last time he used his gun. A year earlier, he said, he fired at a bigger ship that approached his boat late at night without permission. Rio said he then sped away, uncertain whether he had hit anyone on board.

Asked whether he reported the shooting to the police, Rio crinkled his face as if he did not understand. After several silent minutes, he asked: “Why would anyone report that?”

FLOATING ARMORIES

About 25 miles offshore from the United Arab Emirates in the Gulf of Oman, a half-dozen private security guards sat on the upper deck of theResolution, a St. Kitts and Nevis-flagged floating armory. After the men traded war stories about past encounters with pirates, the conversation soon turned to a shared concern: the growing influx of untrained hires into the booming $13 billion-a-year security business.

“It’s like handing a bachelor a newborn,” one guard said, describing how some of the new recruits react when given a semiautomatic weapon. Many of the new hires lack combat experience, speak virtually no English (despite a fluency requirement), and do not know how to clean or fix their weapons, said the guards, most of whom spoke only on the condition of anonymity for fear they would be blacklisted from jobs. Some of the recruits show up to work carrying ammunition in Ziploc bags or shoe boxes.

Security contractors, who face intense boredom in the long breaks between deployments, lifted weights and exercised on the deck of the Resolution. CreditBen C. Solomon/The New York Times

The maritime security industry includes fewer fly-by-night companies today than it did several years ago, according to the guards. But the potential for mishandling attacks — with possibly deadly consequences — has increased over the past year or so, they argued, because the shipping industry has been cutting costs, shifting from four-man security teams to teams of two or three less experienced men.

The 141-foot Resolution is among several dozen converted cargo ships, tugboats and demining barges that have been parked in high-risk areas of the Red Sea, Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, usually just outside national waters. The guards pay as little as $25 per night to stay on the ship (the charge for carrying the men to and from client ships is often several thousand dollars), and check their weapons into a locked storage container upon arrival. Then they wait, sometimes for weeks, for their next job.

Somali piracy spurred many governments to encourage merchant vessels to arm themselves or hire private security, a break from the longstanding practice of nations trying to maintain a near monopoly on the use of force. Meanwhile, growing terrorism concerns led port officials globally to impose tighter restrictions on weapons being carried into national waters. Floating armories emerged as a solution.

On the Resolution, security “team leaders,” most of them American, British or South African military veterans, explained what makes gun battles at sea so different from those on land.

Private maritime security contractors describe their work and living conditions at sea.

By Ben C. Solomon and Catherine Spangler on Publish Date July 20, 2015.

“Between fight or flight,” said Cameron Mouat, a guard working for MNG Maritime, a British company that charters the Resolution. “Out here, there’s just fight.” There is no place to hide, no falling back, no air support, no ammunition drops, he said. Targets are almost always fast moving. Aim is usually wobbly because the ship constantly sways.

Some ships are the equivalent of several football fields in length, too big, these guards contended, for a two- or three-man security detail to handle, especially when attackers arrive in multiple boats.

Discerning threats is difficult. Semiautomatic weapons, formerly a pirates’ telltale sign, are now found on virtually all boats traversing dangerous waters, they said. Smugglers, with no intention of attacking, routinely nestle close to larger merchant ships to hide in their radar shadow and avoid being detected by coastal authorities. Fishing boats also sometimes tuck behind larger ships because they churn up sea-bottom sediment that attracts fish.

“The concern isn’t just whether a new guard will misjudge or panic and fire too soon,” explained a South African guard. “It’s also whether he will shoot soon enough.” If guards hesitate too long, he said, they miss the chance to take preventive measures that can help avoid fatal force, like firing warning shots, flares or water cannons, or incapacitating an approaching boat’s engine.

The armories themselves can be crucibles of violence. Guards climbing off another floating armory, the Seapol One, pulled out their smartphones and showed pictures of the infested, cramped, trash-strewn cabins where eight men bunked.

Like most floating armories, the Seapol One, run by the Sri Lankan firmAvant Garde Maritime Services, had no armed security of its own to police its guests or protect against pirates who might seek to commandeer the arsenal. Most coastal nations oppose the armories, though they can do little to stop them since they are situated in international waters.

None of the guards interviewed knew of any fatal clashes on the armories. But there was no shortage of friction, they said. A Latvian guard, weighing more than 300 pounds and standing well over six feet, relieved himself in the shower because he could not fit in the bathroom stalls. Confronted by other guards, he refused to clean it up.

A smaller transport ship disconnected from the Resolution in the dead of night. CreditBen C. Solomon/The New York Times

Several days earlier a heated argument erupted between two South African guards and their team leader. Unpaid for nearly a month, the men had been abandoned by their security company and left on the Seapol with no way to get back to port.

Kevin Thompson, a British guard, described intense boredom and isolation, which some guards relieved with occasional drinks of forbidden alcohol or by lifting weights, assisted by steroids. Describing the armories, he said, “They’re basically psychological pressure cookers.”

UNSOLVED KILLINGS

The video of the killing of the four men speaks to a survival-of-the-fittest brutality common at sea, according to a dozen security experts who reviewed the footage. They speculated that one gunman, quite likely a private security guard, did all the shooting, using a semiautomatic weapon. And, they said, the four ships at the scene were probably associated with one another, perhaps by shared ownership. “You don’t rob a bank in mixed company,” one former United States Coast Guard official explained.

Last summer, the police in the Fijian capital of Suva closed their investigation into the shootings. They reasoned that the incident did not occur in their national waters, nor did it involve their vessels. Since no Fijian mariners had been reported missing, they concluded none of their citizens were among the victims.

When governments investigate incidents like this, their goal is typically not to find the culprit, said Glen Forbes from OceanusLive, the maritime risk firm. “It’s to clear their name.”

The video, which includes people speaking Chinese, Indonesian and Vietnamese languages, shows three large vessels circling the floating men. A banner that says “Safety is No. 1” in Chinese hangs in the background on the deck of one of the ships. A fourth vessel, which maritime records indicate is a 725-ton Taiwanese-owned tuna longliner called Chun I 217, passes by in the background.

Lin Yu-chih, the owner of the Chun I 217, which remains at sea, said that he did not know whether any of the more than a dozen other ships he owns or operates were present when the men were shot. “Our captain left as soon as possible,” Mr. Lin said, referring to the shooting scene.

Though the date of the shooting is unknown, he said that he believed it occurred in 2013 in the Indian Ocean, where the Chun I 217 has been sailing for the last five years.

Mr. Lin declined to release any details about the crew of the Chun I 217 or the report he said he asked the captain to write about the killings after the Taiwan police contacted his company. Mr. Lin, a board member of the Taiwanese tuna longliners association, said the private security guards on his ships were provided by a Sri Lankan company, which he declined to name. The Taiwan prosecutor’s office, which is looking into the matter, declined to comment.

With one of the world’s largest tuna fleets, Taiwan’s fishing industry is among the nation’s biggest employers and most politically powerful sectors.

Two Taiwanese fishing officials later said that the company authorized to put private security guards on Taiwanese ships was Avant Garde Maritime Services, the same business that runs the Seapol One, the armory in the Gulf of Oman. The company declined to answer questions about its guards or its floating armories.

Tzu-Yaw Tsay, the director of the Taiwanese fisheries agency, declined during an interview to release the Chun I 217’s crew list or captain’s name. He suggested, though, that the men in the water were most likely pirates who had been rebuffed.

“We don’t know what happened,” Mr. Tsay then acknowledged. “So there’s no way for us to say whether it’s legal.”

________________________________

Susan C. Beachy contributed research.

A version of this article appears in print on July 20, 2015, on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: Video Captures 4 Murders, but Killers Go Unpunished.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

[…] Parts: (2 here) – (3 here) – (4 […]

[…] Parts: (1 here) – (2 here) – (4 […]

[…] Parts: (1 here) – (2 here) – (3 […]