Singapore Challenges the Idea That Democracy Is the Best Form of Governance

SPECIAL FEATURE, 24 Aug 2015

Graham Allison – Harvad Belfer Center – TRANSCEND Media Service

Aug 5, 2015 – The American Declaration of Independence asserts that “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” are fundamental, unalienable rights of all human beings — endowed to us by our Creator. According to the Declaration, the primary purpose of government is to establish conditions in which citizens can realize these goals. In comparing governments, it is appropriate to ask how each is performing by these yardsticks.

A reflection of the Singapore financial district is cast on the waters of a reservoir. Singapore celebrates its 50th anniversary of independence Aug. 9. (AP Photo)

As it celebrates the 50th anniversary of its founding under the late Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore is a marvel to behold and applaud. But its success also poses uncomfortable questions for those of us who “know” that Western-style democracy is the best form of government. When one studies the numbers, or asks its citizens, there can be no doubt that Singapore’s government is delivering the results people want. It is also clear that Singapore’s system of governance falls short on many conventional criteria for “good government.” Since most theories of governance hold that good performance requires a good Western-style democracy, Singapore’s record over five decades presents a challenge.

For a provocative analogy, think of countries as if they were hotels and citizens as guests. When considering where to stay, many consumers consult TripAdvisor, which ranks hotels according to guest feedback on various criteria, including location, sleep quality, cleanliness and safety. Rarely do guests offer views about the ownership of the hotel or how it is governed. To make the analogy even more provocative, think of countries as potential destinations for immigrants or even for newborn babies instructing the stork on their preferred destinations. For a prospective citizen choosing between Singapore, a regional competitor (e.g., the Philippines), another former British colony (e.g., Zimbabwe) or even the U.S., what measures of performance might she consider?

Metrics for life stretch from infant mortality through likelihood of being murdered, raped or assaulted, to life expectancy. For every thousand babies born in Singapore, two die within their first year of life, compared with six in the U.S., 24 in the Philippines and 55 in Zimbabwe. Americans’ chances of violent death are 12 times those of citizens of Singapore. Life expectancy in Singapore is 83; it’s 79 in the U.S., 69 in the Philippines and 58 in Zimbabwe.

Freedom “From” and Freedom “To” in Singapore

“Liberty” is more complex, but includes both “freedom from” and “freedom to.” In the first basket, we have freedom from fear of harm; from coercion or exploitation by predatory individuals, corporations or the government itself; and from corruption or stifling government regulations. Relevant metrics for assessing these liberties include many categories in the World Bank’s measures for “good governance:” basic safety and security provided by law and order and an even-handed regulatory system that treats individuals equally and provides a predictable environment for entrepreneurship and investment. “Freedom to” encompasses basic civil liberties: freedom to speak and express one’s views, to worship, to assemble and to participate in governance.

Singapore stands at the top of the international competition on “freedoms from:” It ranks first internationally in the World Bank’s measure of “regulatory quality” and second on The Heritage Foundation’s scale of economic freedom, while the U.S. comes in 13th. Gallup’s 2014 World Poll found that eight in 10 Americans see “widespread corruption” in the U.S. government, compared with seven in the Philippines, six in Zimbabwe and one in Singapore. On the World Bank’s “rule of law” index, Singapore scores in the 95th percentile of nations, the U.S. scores in the 91st, the Philippines in the 42nd and Zimbabwe in the 2nd. With a population of almost six million, Singapore’s incidents of robbery were only a seventh of Boston’s, which has a population of only 650,000.

When we turn to “freedom to” metrics, however, one-party Singapore scores well below the U.S. on three of our core freedoms: “freedom of expression and belief,” “associational and organizational rights” and “political pluralism and participation.” In its overall freedom score, the U.S. earns Freedom House’s highest ranking, Singapore stands in the middle of the contenders and the Philippines about halfway between the two. Moreover, Pew Research, which conducts a survey on government treatment of religion, finds that Singapore imposes “very high” barriers on the exercise of faith.

Pursuit of happiness is the most far-reaching of our rights: if the stork dropped one of us off in a specific country, what would our prospects be to eat, grow, learn and realize our potential?

Beginning with basic economic security and survival, Gallup found in 2014 that only half as many Singaporean families found themselves unable to afford food at some point during the previous year as Americans. Bloomberg’s survey found Singapore to have the healthiest population in the world — the U.S. ranking 33rd, the Philippines 86th and Zimbabwe 116th. Currently, 86 percent of Singaporeans report that they are “living comfortably or getting by” on their current income, while only 77 percent in the U.S. say the same. Students in Singapore’s schools rank second in the world in mathematics out of countries and regions surveyed, and third in both science and reading, while American students come in 36th, 28th and 24th respectively. Singapore offers graduates the best setting in the world to do business and the 6th easiest in which to start a business, while the U.S. ranks 7th and 46th respectively.

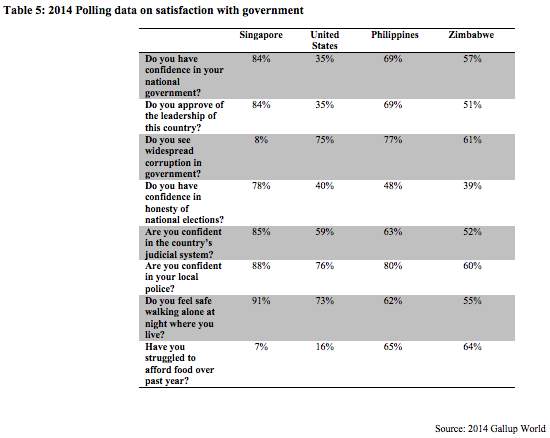

When one asks “hotel customers” for feedback, the results are even more troubling for Americans. As the table below shows, four out of five Singaporeans are satisfied customers. They have confidence in their elections, their judicial system, their local police and their national leadership. In contrast, only one in three Americans has confidence in our national government and the country’s leadership; fewer than half regard elections as honest; and three-quarters of the population sees widespread corruption in government.

Therefore, what? I am not yet ready to give up my belief that democracy is, as Churchill quipped, the worst form of government known to man, except for all the others. But when I stop to examine the facts about Singapore, I am left with more questions than answers. Is an open, competitive Western-style democracy required to deliver the life, liberty and happiness citizens want? As Singaporeans celebrate their 50th birthday and look to the decades ahead, can their current system of government continue to meet the customers’ demands? Will wealthier citizens not demand a greater role in governing themselves?

Therefore, what? I am not yet ready to give up my belief that democracy is, as Churchill quipped, the worst form of government known to man, except for all the others. But when I stop to examine the facts about Singapore, I am left with more questions than answers. Is an open, competitive Western-style democracy required to deliver the life, liberty and happiness citizens want? As Singaporeans celebrate their 50th birthday and look to the decades ahead, can their current system of government continue to meet the customers’ demands? Will wealthier citizens not demand a greater role in governing themselves?

Is wide-open, American-style democracy with an unconstrained press a necessary prerequisite for sustainable delivery of life, liberty and happiness? Or is it instead another good thing in itself — independent of whether it contributes to or degrades life, liberty and happiness?

Was Lee Kuan Yew correct in his belief that Mandarins (in the tradition of Plato’s philosopher kings) who put the public good above their personal interests are necessary for good governance? If so, will Singapore be able to sustain such high levels of talent and sacrifice in its public service? And is there something about the current practices in American democracy that make that less likely? As more Americans see D.C. as an acronym for “Dysfunctional Capital,” these are questions that deserve a rigorous debate.

________________________________

Graham Allison, Director, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs; Douglas Dillon Professor of Government, Harvard Kennedy School.

Go to Original – belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.