The Teflon Toxin – Part 3: How DuPont Slipped Past the EPA

ENVIRONMENT, 24 Aug 2015

Part 1: DuPont and the Chemistry of Deception

Part 2: The Case Against DuPont

Aug. 20 2015 – Mike Romine grew up in Blennerhasset, West Virginia, not far from DuPont’s Parkersburg plant. Throughout his childhood and young adulthood, Romine was probably exposed through his drinking water to C8, a slippery, soap-like chemical used to make Teflon pans and Stainmaster carpet and hundreds of other products. His home was served by the Lubeck water district, one of six districts near the plant later found to be severely contaminated with the chemical, but his greatest exposure to C8 almost certainly came from working at the DuPont plant, where he was a welding inspector.

Romine spent some of his time in the company’s Teflon division, and he particularly remembers taking part in the “Teflon shut down,” a spring-time ritual. For a few days each year, the company would shut down operations in the plant to prepare for the coming year. Romine helped install new piping. He didn’t know what C8 was at the time, but there was a white powdery substance dusting many of the surfaces in the plant. “It’s on the pipe, on the inside of it,” said Romine. “You don’t all the time have on gloves. It’s on your coveralls.”

Twelve years ago, when Romine was 58, he was diagnosed with kidney cancer. No one in his family had ever suffered from this rare disease. Surgeons removed the cancerous organ, leaving Romine with reduced kidney function. Now he has to urinate frequently and his doctors have suggested that he change his diet and refrain from running, an activity that had been a regular part of his life before the surgery. Every six months he must return to the doctor to have his remaining kidney checked.

Today, Romine has mixed feelings about DuPont. He worked for the company full-time as a contractor for eight years, and his best friend was employed in one of DuPont’s labs. “In my heart, I felt I was DuPont,” said Romine, who has enduring respect for the company. “DuPont has really good safety rules, good people, good personnel,” he said. “I enjoyed working down there.”

Still, for all the good DuPont has done his community as an employer and as a supporter of local organizations and sports teams, Romine is concerned that the company has not been fully honest — especially after a panel of scientists, funded by a class-action settlement, found that kidney cancer and five other diseases had been strongly linked to C8 exposure. “DuPont made me money,” he said, “but I certainly think now they needed to come clean with whatever happened.”

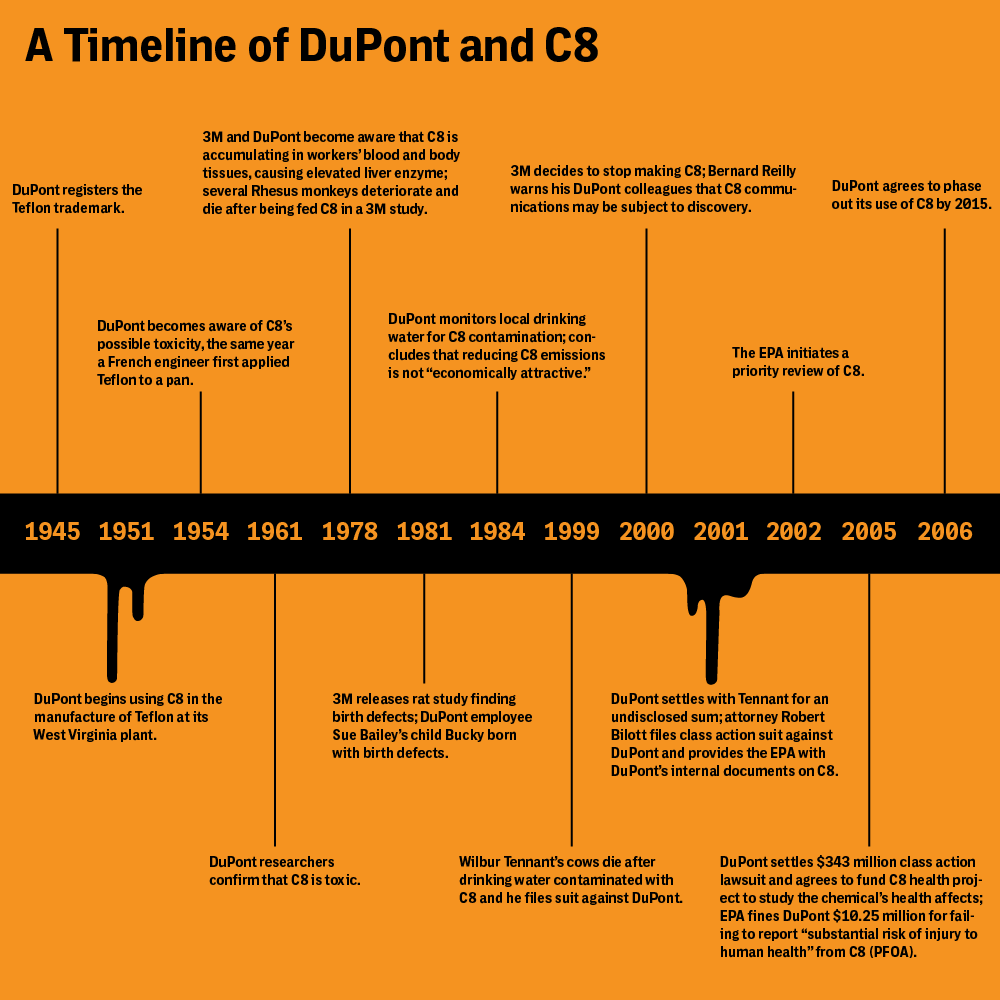

In March 2001, an attorney named Robert Bilott embarked on an ambitious plan to force DuPont to come clean — to tell what it knew about C8 and, he hoped, eliminate the chemical from the water consumed by Romine and others throughout the country. Bilott sent packages of evidence to the federal Environmental Protection Agency, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, and the Attorney General of the United States, among other regulators. Inside were more than 100 documents he had received through discovery in a lawsuit he had filed in 1999 on behalf of a West Virginia farmer named Wilbur Tennant, whose cows died after being exposed to PFOA, also called C8 because of the eight-carbon chain that makes up its chemical backbone. The documents showed that DuPont, which since the early 1950s had used C8 to manufacture Teflon and other products in its Parkersburg plant, had known for years that C8 posed health dangers and had spread beyond the company’s West Virginia plant into local sources of drinking water.

Bilott even arranged to go to Washington, D.C., to personally present his findings to the EPA. When DuPont attorneys learned about Bilott’s plan, they tried to stop him with a last-minute gag order. They were unsuccessful, however, as Bernard Reilly, one of the company’s in-house lawyers, noted in an email to his son on March 27, 2001:

Court yesterday did not agree to shut up plaintiff lawyer in our Parkersburg situation and today he testifies an EPA hearing and will try to slam us one more time.

Bilott did make his case to the federal regulators and reiterated the request he made in the letter that accompanied his evidence, that the agency regulate C8 under the Toxic Substances Control Act “on the grounds that it ‘may be hazardous to human health and the environment.’”

By some measures, Bilott has in fact been successful in slamming DuPont, but 14 years after he sent his evidence to the EPA, the company has managed to avoid a full reckoning for its actions. And C8, which is in the bloodstream of 99.7 percent of Americans, remains unregulated at the national level.

During the five decades in which DuPont used and profited from C8, the company had only infrequently discussed the chemical with environmental authorities, and it kept most of its extensive internal research on the chemical confidential. After Bilott sent out his packages of evidence, however, DuPont’s relationships to government agencies shifted dramatically. Bilott’s revelations had the power to tarnish the company’s reputation and lead to huge legal and cleanup costs, so DuPont focused on weathering the scrutiny of regulators and keeping its name — and profits — unscathed.

Although Bilott and his clients eventually prevailed in a ground-breaking class-action lawsuit filed the same year he approached the EPA, that settlement had limited applicability. Action by the EPA could hold DuPont accountable nationally.

Locally, the matter was well in hand. Several regulators at the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection had already shown their allegiance to the company, one of the state’s biggest employers. In October 1996, after the regional office of the EPA began investigating a complaint about one of the company’s landfills, Eli McCoy, the director of the West Virginia DEP, allegedly sent the company a document “to aid DuPont in diffusing any potential enforcement action,” as Bilott put it in a letter to the EPA. After a few weeks of negotiation, the West Virginia DEP signed off on a consent decree, in exchange for a mere $200,000 penalty and minor upgrades from DuPont. McCoy then went to work for a consulting firm DuPont hired to help it comply with that agreement.

He wasn’t the only regulator who followed the money. As Callie Lyons reported in her 2007 book, Stain-Resistant, Nonstick, Waterproof, and Lethal, three attorneys handling C8 at the West Virginia DEP emerged on the other side of the revolving door as employees of the same local law firm that defended the chemical on behalf of DuPont. Reached for comment, McCoy said that he did not recall details of the matter, noting that he had not worked for the West Virginia DEP for 18 years.

The EPA presented a potentially more challenging situation. The federal agency has the authority to regulate C8 under several laws, including the Toxic Substances Control Act and the Clean Water Act. Through either route, regulation could trigger hefty cleanup costs. In 2002, the EPA initiated what is called a “priority review,” a critical first step toward regulation, which entails assessing a chemical’s risk to determine whether it should restrict or ban it. The EPA puts a special priority on chemicals that are toxic, persist in the environment, and accumulate in people’s bodies. C8 fit the bill on all three counts.

In response, DuPont assembled a high-powered team that included former EPA officials to oversee its C8 communications with the federal agency. Michael McCabe, a consultant who managed the company’s communications and C8 strategy with the EPA starting in 2003, had served as deputy administrator of the agency until 2001. Linda Fisher, a lawyer who succeeded him in the No. 2 position at the EPA, was also central to DuPont’s C8 campaign. In fact, just over a year after leaving the agency in June 2003, Fisher was already deeply involved in the defense of C8. It surely didn’t hurt that William Reilly, who led the EPA from 1989 to 1993, sat on DuPont’s board of directors.

DuPont’s C8 team benefited from inside information about what regulators were thinking about the chemical, according to testimony McCabe gave when he was deposed in 2007. They knew what was in some of the agency’s documents before they became public and saw at least one presentation before it was given. The DuPont team even drafted quotes to be attributed to EPA officials, which DuPont later embedded in press releases. In his deposition, McCabe said the practice of asking the EPA for a quote was “customary.”

Several other firms also served as consultants, including a company called the Weinberg Group. In an April 2003 memo, P. Terrence Gaffney, the group’s vice president for product defense, proposed “a fresh new approach” to help DuPont with its defense of C8:

The constant theme which permeates our recommendations on the issues faced by DuPont is that DUPONT MUST SHAPE THE DEBATE AT ALL LEVELS. We must implement a strategy at the outset which discourages governmental agencies, the plaintiff’s bar, and misguided environmental groups from pursuing this matter any further than the current risk assessment contemplated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the matter pending in West Virginia. We strive to end this now.

The memo bragged that the company had long experience in managing chemical PR crises. “Beginning with Agent Orange in 1983,” Gaffney wrote, “we have successfully guided clients through myriad regulatory, litigation, and public relations challenges.” Weinberg’s proposal included using “focus groups of mock jurors to determine the best ‘themes’ for defense verdicts,” retaining “leading scientists to consult on the range of issues involving PFOA so as to develop a premium expert panel,” and efforts to “reshape the debate by identifying likely known health benefits of PFOA exposure by … constructing a study to establish not only that PFOA is safe … but that it offers real health benefits.”

The “Weinberg memo” gained a level of infamy when a copy was made public in 2006. Two years later, Rep. John Dingell of Michigan brought it up in a Congressional investigation, noting, “The tactics apparently employed by the Weinberg Group raise serious questions about whether science is for sale at these consulting groups.” DuPont, which has asked the judge in the upcoming trials to exclude any mention of the Weinberg Group, denied that it hired the consulting company to work on C8. But court documents, including invoices (one of which mentions PFOA specifically), suggest otherwise. Two years later, the Weinberg Group again offered its services to DuPont and in an email made reference to “the C8/fluorocarbon chemicals controversy” and noted that “the Weinberg Group which offers services in evidence-based advocacy was given some discrete assignments in developing strategies for helping DuPont in its advocacy.” Reached by telephone, Matthew Weinberg, the CEO of the Weinberg Group, declined to comment, but then added: “The Weinberg Group is no longer engaged in any of this work. We’re an FDA consulting firm.”

A glass of filtered water sits on Ken Wamsley’s kitchen table in Parkersburg, West Virginia. Photo: Maddie McGarvey for The Intercept/Investigative Fund

Although the EPA is specifically charged with the task of protecting the public by reducing the risk of exposure to commercial chemicals, the agency is also limited in what it can require of industry. Unlike the Food and Drug Administration, which reviews prescription medications before they can be brought to market, the EPA has little power to prevent a company from using a chemical before it is proven to be safe. Although in Europe chemicals must be proven safe before they are put on the market, in the United States — despite repeated revelations that widely used industrial chemicals (including PCBs, fire retardants, and many others) have severe public health and environmental effects — chemical manufacturers have few legal obligations to ensure that their products are safe. In America, killer chemicals are essentially innocent until proven guilty.

Another conundrum of our chemical regulatory system is that regulators must depend on the manufacturers for data on the chemicals they wish to regulate. Yet this information can be difficult to obtain, precisely because the chemicals are unregulated. To move forward with the priority review of the chemical it had begun in 2002, the EPA needed to know how polluted with C8 were the water, air, soil, plants, animals, humans, and food sources near the DuPont plant in West Virginia.

DuPont and other companies that used C8, including Daikin, 3M, and Dyneon, quickly volunteered to provide the information. The companies came up with several research proposals and then together, represented by an entity called the Fluoropolymers Manufacturers Group, lobbied the EPA to make the agreement regarding the chemical completely voluntary. Among the alleged benefits of the voluntary option were “quicker implementation” and that “monitoring data can be obtained sooner,” members of the manufacturers group argued at a January 2004 meeting with the EPA. Of course, the problem with a voluntary agreement is that it would be unenforceable.

Without a legally binding agreement, the EPA was unable to enforce the terms of its interactions with DuPont. Mostly, the agency relied on negotiated consent agreements. If DuPont didn’t like the terms, it could simply walk away from the deal. In one of these agreements, a regional consent order dated March 2002, DuPont agreed to provide clean water to residents near its plant whose drinking water was contaminated above a certain level. Despite the fact that the company had set its own internal safety limit for the maximum amount of C8 in drinking water at 1 part per billion (ppb), in the consent order the company agreed only to a limit of 14 ppb. Two months later, that “trigger level” was raised to 150 ppb, where it stayed until 2006.

While it was pressing for an unenforceable national agreement, DuPont was also negotiating the future of C8. When its legal troubles concerning C8 had first begun, the company had clearly banked on continuing to use C8, as evidenced by its 2002 decision to invest $23 million in a facility to produce it. But by 2005, after DuPont settled the class-action suit over water contamination around its West Virginia plant, according to the sworn testimony of McCabe, the company told regulators it was open to the possibility of phasing out C8.

On this front, too, the company set the terms. In an October 2005 meeting with the EPA, McCabe presented a slide about the company’s “critical needs,” among them that “EPA restate safety of products and no health effects.” McCabe also asked the EPA to make a public statement acknowledging DuPont’s leadership in withdrawing C8, and to ensure that all the other companies using the product also be required to retire it.

Around this time, DuPont reached out to the Bush White House, as emails that emerged in discovery showed. McCabe admitted in a deposition that DuPont wanted to let the EPA know that the Bush administration was supportive of its proposal. McCabe, in his deposition, said that such contacts were “not unusual.”

Perhaps it is also not unusual that all of the company’s pending questions around C8 — whether the company would be fined for withholding information about the chemical from the government; whether it would retire its chemical; and whether it would be subject to binding regulation by the EPA — were resolved in a matter of months, shortly after the contacts between DuPont and the White House.

A month after the company finalized its voluntary commitment to research the extent of contamination around its West Virginia plant, the EPA resolved the matter of the fine. The settlement reached that month stemmed from DuPont’s unlawful failure to alert the EPA about information regarding its risk to human health. Specifically, the company withheld what it knew about the toxicity of C8, the presence of C8 in drinking water, the presence of C8 in the blood of people living near its West Virginia plant, and in the babies of some of its female workers, two of whom were born with birth defects.

At the time, the EPA trumpeted the fact that its $10.5 million fine of DuPont was “the largest civil administrative penalty EPA has ever obtained under any federal environmental statute.” The settlement also required the company to spend $6 million on “supplemental environmental projects.” Less remarked upon was the fact that the fine was a small fraction of the maximum $300 million the agency technically could have collected.

The total $16.5 million penalty was an even smaller fraction of the $1.6 billion in quarterly sales that DuPont’s performance materials division was enjoying at that time — less, in fact, than the division’s sales in a single day.

The following month, DuPont finalized the specifics of its one significant concession: to participate in what the EPA called a “global stewardship program,” which in practice meant a 95 percent reduction in C8 emissions by 2010 and eliminating use of the chemical by 2015. In January 2006, Susan Stalnecker, a DuPont vice president, sent a letter to Stephen Johnson, then head of the EPA, confirming the agreement and alluding to DuPont’s plan to replace C8 with another chemical, noting that “success in this effort will depend on timely review and approvals for these new products.”

As McCabe’s deposition shows, the plan was carried out according to the company’s specific terms. As DuPont had requested, the EPA invited the seven other companies that used C8, including 3M, to also participate in the stewardship program, and all agreed to reduce their emissions and phase it out. And, as DuPont had requested, the EPA issued reassuring statements about C8 and the products that contained it. On January 25, 2006, in the announcement of the global stewardship program, the agency said that “to date EPA is not aware of any studies specifically relating current levels of PFOA exposure to human health effects.” On the same day, DuPont issued a press release containing the agency’s statement.

Five days later, a draft report by an EPA Science Advisory Board that was reviewing C8 found the chemical to be a “likely human carcinogen.” DuPont vice president Susan Stalnecker sent an email to her team:

Publicity around SAB report has linked the Teflon brand to cancer. Coverage has been broad in print and network media. Significant disruptions in our markets and are [sic] consumers are very, very concerned.

What’s telling about the email is the company’s attitude toward the EPA and its assumption that of course the agency would cooperate in the damage-control campaign.

In our opinion, the only voice that can cut through the negative stories, is the voice of EPA. We need EPA … to quickly (like first thing tomorrow) say the following: Consumer products sold under the Teflon brand are safe.

According to a February 17, 2006, email from Susan Stalnecker to DuPont CEO Charles Holliday, Linda Fisher then contacted Marcus Peacock at the EPA and expressed DuPont’s concerns about the need for the EPA to make a statement. That February, a group of high-profile health ethicists and epidemiologists hired by DuPont to consult on C8 advised the company against making any further public statements denying that C8 poses a risk to human health.

On March 2, 2006, the EPA obligingly issued another statement saying, “The agency does not believe that consumers need to stop using their cookware, clothing, or other stick-resistant, stain-resistant products.” The agency’s own research has since shown that consumer products are in fact a source of C8 exposure. While Teflon-coated pans appear to account for only a small amount of Americans’ C8 exposure, other consumer products, such as coatings for stain-resistant carpets, floor wax, and upholstery, are greater sources of contamination, according to a 2009 EPA analysis of 116 consumer products.

McCabe, in his December 2007 deposition, insisted that the highly favorable public statements by the EPA were “not a quid pro quo” for the company’s agreeing to phase out C8.

The Intercept requested comment from McCabe and Fisher but received no reply. Stalnecker did not respond to emails requesting comment. The EPA declined to comment on the suggestion that it had engaged in a quid pro quo with DuPont. In a statement (see below), DuPont asserted that Fisher “has never represented DuPont on PFOA matters with the EPA.”

DuPont has phased out the use of C8, but in other respects the company simply failed to live up to its end of the bargain. DuPont did file three reports about C8 contamination in air, water, soil, and biota around its Parkersburg plant in 2008. But a team of independent peer reviewers found that these reports suffered from “significant limitations and omissions” and asked the company to fill in several gaps. Among dozens of additional requests, the reviewers asked DuPont to perform more frequent and extensive sampling of the Ohio River; to expand the 2-mile area where it was measuring the impact of C8 exposure; and to provide more data on the presence of C8 in local water, soil, air, fish, game, and meat, and in the blood and breast milk of residents in the area of the plant. DuPont then revised its report, but the EPA again requested that extensive additional research be done in 2010.

In 2011, the EPA reiterated the need for more data, noting in particular that the company did not test milk from cows in contaminated areas. The next year, without fulfilling many of the reviewers’ outstanding requests, DuPont submitted what it said would be the final version of the report it had promised under the voluntary agreement it had reached with the EPA in 2005. At the time the agreement was hammered out, proponents had noted that it would be public — and, as such, that people would know if the company failed to keep its promises. But little public mention was made when DuPont submitted in November 2012 its final report that was supposed to help with monitoring C8. Without any legal recourse, the EPA quietly filed it away, and a national standard for C8 contamination in drinking water was never set.

DuPont Chambers Works plant in Deepwater, New Jersey, Friday, Jan. 5, 2007.

Photo: William Bretzger/The News Journal

Meanwhile, regulators in New Jersey were waging their own battle against C8. Back in 2006, the state began to consider setting a drinking water standard for the chemical. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection knew there was some contamination around a DuPont plant in Deepwater, a community about 20 miles down the Delaware River from Philadelphia. In September 2003, groundwater tests under the plant had revealed C8 levels as high as 46.6 ppb. In some workers at the New Jersey plant, in 2007, blood levels were very high; one was measured at 4,400 ppb. According to data from the CDC, blood levels of the chemical in the general U.S. population in 2007 averaged around 4 ppb.

A group of 15 scientists and water experts known as the New Jersey Drinking Water Quality Institute was responsible for proposing drinking water standards in the state. Their task was clearly laid out by New Jersey law: to determine maximum contaminant levels, including the exact amount of a chemical that, when drunk by a million people over their lifetimes, causes no more than one case of cancer. For more than 20 years, the institute had been crunching numbers to arrive at the maximum allowable level of a given contaminant and then submitting the figure to the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. During most of that time, the group had carried out its charge with little intervention and even less fanfare.

Eileen Murphy, head of the Division of Science, Research and Technology at the New Jersey DEP, was closely studying C8 at the time and was invited, along with members of her staff, to meet with DuPont executives.

Murphy was investigating whether C8 was dangerous. The EPA had already classified the chemical as a likely human carcinogen — a term applied to chemicals that cause tumors in more than one species — and she knew about numerous studies that indicated it to be toxic. She said as much at the meeting. Murphy and the DuPont representatives then “disagreed widely over the interpretation of the toxicology studies,” Murphy remembered recently. “They said our interpretation was overly conservative.” Afterward, “we never heard from them again,” Murphy said. “They just went higher than us. And liked that path better.”

In 2007 the Drinking Water Quality Institute came up with the figure for C8 and sent it to the New Jersey DEP. The proposed standard was .04 ppb.

When DuPont learned about the proposal, a tiny fraction of the level the company had helped West Virginia set a few years before, McCabe and his communications team went to work. If the proposed safety level were enacted, the company could face enormous cleanup and liability costs. McCabe drafted letters arguing that New Jersey’s numbers were far too low and sent them to the commissioner of New Jersey DEP, the governor’s office, and the state’s Economic Development Office.

DuPont representatives later came to subsequent meetings at the New Jersey DEP, to which Murphy was no longer invited. Not long after, in October 2008, Murphy was preparing to submit for peer review an article about C8 in New Jersey water systems that one of her colleagues had written, when Lisa Jackson, who was then New Jersey’s DEP commissioner, asked her to stop its progress toward publication. The article explained the agency’s logic for setting .04 as a safety standard and noted that it had already detected C8 above that level in five drinking water systems.

“I did it anyway,” Murphy recalled in an interview this past spring. “I was reassigned after that.” Indeed, shortly after Murphy submitted the article for peer review, she was relieved of her position as division head, in which she had managed a team of PhD scientists like herself. Instead, Murphy was given a post with few responsibilities and in the months before she left the agency filled her time by working on low-level projects and helping the secretaries with their typing. Lisa Jackson went on to serve as administrator of the federal EPA under Barack Obama. She is currently vice president of environment, policy, and social initiatives for Apple. The Intercept left repeated messages for Lisa Jackson requesting comment and attempted to contact her via email, but received no reply.

In September 2010, the Drinking Water Quality Institute began to move forward with the .04 water standard, nine months after Chris Christie became of governor of New Jersey. Christie had made it clear, with his “red tape commission” and pro-business executive orders, that he was unlikely to pass new regulations. But the Christie administration went even further; not only did it apparently block the proposed standard, it also effectively disbanded the water quality group. Although the institute and its committees had met nearly 50 times in the five years prior, after the September 2010 meeting the group did not convene again for almost four years.

Meanwhile, the New Jersey DEP had created a new body called the Science Advisory Board, to advise on a number of environmental issues, including water quality. In 2011, three DuPont scientists, each of whom have worked on C8, were appointed to the board.

This past spring, the Drinking Water Quality Institute met for only the second time since it attempted to set a C8 standard in 2010 (the first was in 2014). The chair of the recently resurrected group, a toxicology professor named Keith Cooper, told me that he’s committed to setting a new drinking water standard for C8. “These recommendations are for the health and safety of the people of New Jersey,” said Cooper, who added that he would do everything he could to push back if the standards fail to move forward this time around, including bring the matter to the current DEP commissioner, Bob Martin. “First I will meet with Martin and then I will request to meet with Christie.”

But because the last set of proposed regulations never made it into law and have officially sunset, the whole process must begin again, which means at least another year of legal, scientific, and administrative preparations. The process is likely to take much longer. By that point, Christie may no longer be governor, but DuPont will have succeeded in delaying and perhaps permanently deferring its environmental accountability for contaminating New Jersey waters with C8. The Christie administration did not reply to requests for comment.

Despite all these setbacks, it is still not too late for the EPA to regulate C8 and require companies such as DuPont to pay for cleanup costs. Attorney Robert Bilott clearly hasn’t given up on the cause, though there is a certain pathos in the letter he sent the EPA this January, which begins this way:

We first wrote to US EPA and WVDEP in March of 2001 — over 13 years ago — to alert your Agencies to the imminent and substantial threat to human health and the environment posed by the contamination of human drinking water supplies with perfluorooctanoic acid.

Indeed, there is voluminous, and repetitive, correspondence about C8 between the agency and the lawyer. In 2010, the agency responded to his urging to set a national drinking water level with a promise that it would do so by the end of that year. Then, in 2011, the agency promised to set the level by the end of that year. And, again, in a February 2012 letter, the EPA claimed it would take action in the “next few months” or by “early 2013.”

A February 23, 2015 letter from Susan Hedman, a regional administrator of the EPA, has a similar ring, saying that a lifetime health advisory may be developed “later this year,” at which point the agency might just possibly reevaluate its 2009 consent order with DuPont.

Mike Romine stands outside of his home in Parkersburg, West Virginia, on Wednesday, August 5, 2015.

Photo: Maddie McGarvey for The Intercept/Investigative Fund

Recent testing by the EPA found C8 in 94 water systems serving a total of 6.5 million Americans. The minimum testing level was .02 ppb, which is far greater than new estimates of an approximate safe level in drinking water. If the EPA does ever decide to regulate C8 and set a national drinking water standard, DuPont might still be able to avoid cleanup costs, since the company has now cut its ties with the chemical. In July, DuPont spun off its chemical division into a separate company called Chemours. DuPont has promised to cover whatever settlements result from the crop of personal injury claims scheduled to come to trial in the fall. But, if they’re ever levied, cleanup costs for the C8 DuPont leaked into the larger environment, which could add up to many billions of dollars, could fall to Chemours, a much smaller company.

Over the years, as letters have flown back and forth between lawyers and various agencies, levels of the chemical in human blood throughout the United States appear to be dropping. That is good news for the people whose systems the chemical is exiting — the chemical has a half-life in humans of about four years — though not necessarily for the planet at large, since the chemical isn’t going away. It’s simply being diffused, spreading throughout the world’s water systems.

Meanwhile, as it was dispensing with its C8 problem, DuPont was busy introducing new chemicals to replace the old one. Since at least 2009, the company has been using what it calls the “Capstone” line of surfactants and repellants, which in July became the property of Chemours. The replacement molecules are reported to have a six or fewer fluorinated carbon chain as their base but little more about them is known since their chemical make-up is proprietary. FDA records obtained by the Environmental Working Group show that since 2005 the agency approved at least 10 “fluorochemicals” that could replace C8 in food packaging, though there is little public record of health risk assessments being performed on them.

This spring, an international group of scientists and environmental advocates issued a public warning about these replacement chemicals. The “Madrid Statement,” as it’s called, noted that while the “shorter-chain” chemicals used to replace C8 may not stay in human bodies quite as long, “they are still as environmentally persistent as long-chain substances or have persistent degradation products.” The statement, which has now been signed by hundreds of scientists, continued: “Because some of the shorter-chain PFASs are less effective, larger quantities may be needed to provide the same performance.”

The Madrid Statement called on governments to require companies to conduct more toxicological testing and to make chemical structures public. And this year, after it banned the chemical, the European Union proposed a global ban on C8, which is now being produced in India, Russia, and China.

The United States has yet to set a level that’s safe to drink. As Mike Romine in West Virginia sees it, there is something terribly wrong with letting people be exposed to a chemical that can hurt them.

Such thinking was the basis for the class-action suit targeting the plant in West Virginia where Romine worked and the subsequent settlement requiring DuPont to provide clean water to tens of thousands of people in nearby water districts. In a few weeks, the first of approximately 3,500 personal injury claims resulting from that class action will come to trial in Columbus, Ohio. We may soon know if a jury will hold DuPont accountable for the lives it has forever altered, through chemistry.

But whatever happens in those claims, the overwhelming majority of Americans have also been exposed. So far, no one has offered them any recourse or offered to ensure that their water is safe to drink.

EDITOR’S NOTE: DuPont, asked to respond to the allegations contained in this series, initially declined to comment due to pending litigation.

In previous statements and court filings, however, DuPont has consistently denied that it did anything wrong or broke any laws. In settlements reached with regulatory authorities and in the class-action suit, DuPont has made clear that those agreements were compromise settlements regarding disputed claims and that the settlements did not constitute an admission of guilt or wrongdoing. Likewise, in response to the personal injury claims of Mike Romine, Jeromy Darling, and others, DuPont has rejected all charges of wrongdoing and maintained that their injuries were “proximately caused by acts of God and/or by intervening and/or superseding actions by others, over which DuPont had no control.” DuPont also claimed that it “neither knew, nor should have known, that any of the substances to which Plaintiff was allegedly exposed were hazardous or constituted a reasonable or foreseeable risk of physical harm by virtue of the prevailing state of the medical, scientific and/or industrial knowledge available to DuPont at all times relevant to the claims or causes of action asserted by Plaintiff.”

Before the publication of this article, DuPont provided the following statement:

DuPont has worked collaboratively with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to meet and exceed the Agency’s program requirements on PFOA. We have never requested nor have we received special consideration or treatment from the Agency regarding PFOA.

In 2006, EPA and the eight major companies in the industry, including DuPont, launched the 2010/15 PFOA Stewardship Program, in which companies committed to reduce global facility emissions and product content of PFOA and related chemicals by 95 percent by 2010, and to work toward eliminating emissions and product content by 2015.

Prior to the development and implementation of the PFOA Stewardship Program, EPA posted the following statement on the use of consumer products on the Agency’s website. “The information that EPA has available does not indicate that the routine use of consumer products poses a concern. At present, there are no steps that EPA recommends that consumers take to reduce exposures to PFOA.” The statement is the Agency’s recommendation, and DuPont had no involvement in its development.

With respect to Linda Fisher, for over 30 years, she has served with distinction as a leader in environmental protection, health and safety for the EPA and later for private businesses. Throughout her career, Linda has upheld the highest standards of integrity and ethical behavior, and has fully complied with the EPA’s ethics rules since leaving EPA, and later as DuPont’s Chief Sustainability Officer. In her role as Chief Sustainability Officer Linda was instrumental in helping DuPont design and implement its Global Stewardship Program to ensure the company met its commitments with the EPA. Linda has never represented DuPont on PFOA matters with the EPA.

Our work with the Agency has been and remains transparent, and we have cooperated in every way with the spirit and letter of applicable laws and EPA guidelines.

When contacted by The Intercept for comment, 3M provided the following statement.

In more than 30 years of medical surveillance we have observed no adverse health effects in our employees resulting from their exposure to PFOS or PFOA. This is very important since the level of exposure in the general population is much lower than that of production employees who worked directly with these materials,” said Dr. Carol Ley, 3M vice president and corporate medical director. “3M believes the chemical compounds in question present no harm to human health at levels they are typically found in the environment or in human blood.

___________________________________

Part 1: DuPont and the Chemistry of Deception

Part 2: The Case Against DuPont

Sharon Lerner is a Brooklyn-based journalist and author who covers health and the environment. fastlerner@gmail.com

Ava Kofman and Sheelagh McNeill contributed to this story.

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute.

Go to Original – firstlook.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

[…] Part 3: How DuPont Slipped Past the EPA […]