Joy in the Midst of Haiti’s Election

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN, 21 Mar 2016

Barbara Rhine – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Know that joy is rarer, more difficult, and more beautiful than sadness. Once you make this all-important discovery, you must embrace joy as a moral obligation.”

— André Gide

25 Feb 2016 – It is 7 AM on Monday October 19th, and I am in Port au Prince on a hastily-planned quick trip. Jet-lagged, I loll in the back seat of our rented van and try to wake up. Traffic here in the capitol of Haiti is a wrangle. Every variety of motor vehicle operates on the city’s streets and roads that alternate between pavement, dirt, stones and ruts. There are few traffic signals, and often no lines for lanes, left-turn or otherwise.

Pedestrians crowd along the edges of the traffic and head across the streets at every angle. Many women and the occasional man manage all this with loads balanced on their heads. Whole enterprises sprawl by the roadsides in the open air.

Women sit close to the dirt to hawk their fruit.

Boys are at the ready to charge, fix or sell cell phones. Men find a way to set up to shine and repair shoes.

School kids in uniforms bound about.

The year is 2015, the first time in eleven years that the governing forces have permitted Fanmi Lavalas, the party of former President Jean Bertrand Aristide, to run a candidate for President. Our group of four is here for a brief visit less than a week before the presidential election, scheduled for October 25th. The other three are Pierre, a Haitian activist who lives and works in California; Dave, a retired union official and labor organizer; and Margaret, a radio talk-show host in Los Angeles who also works on international women’s issues. Our hostess at the guest house, where I have a huge room with three bunk beds all to myself, is stuffed in the van’s way back with Margeret. A Lavalas activist, who hosted me on my only previous visit to Haiti, is in the front with the driver.

We have a huge task to accomplish in our short time here. We are to take reports of what happened during the legislative elections held on August 9th, to examine the set-up for the presidential round on October 25th, and to report all this to the press, both in Haiti and back home. There are fifty-four presidential candidates on the ballot. Everywhere there are election signs and billboards, for a bewildering array of parties, candidates and offices.

The Lavalas guy and I talk and joke about that previous trip. The 2010 earthquake occurred during our stay, and because this man’s house held up I, my husband and my daughter emerged unhurt and alive. I remember what it was like that first night, right after the temblor. Afraid of aftershocks, we all slept outside in the courtyard. There were no sirens, no earth-moving equipment, no official rescue operations at all that we saw. But there were women’s voices, singing into the early morning hours. Hymns? African chants? I have no idea, but the simple peaceful melody was a great comfort.

My article on the earthquake in Counterpunch:

http://www.counterpunch.org/2010/02/04/keep-what-you-have-but-leave-the-rest/

Five years later I am here because Pierre, one of the nicest people I know, has talked me into it. He is concerned that current President Michel Martelly is ushering in a new era of dictatorship that resembles the time of the Tonton Macoute, a special operations unit within the Haitian paramilitary force created in 1959 by François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. The name comes from a Haitian bogeyman known to snare unruly children in a gunny sack and carry them off to be eaten for breakfast. If you want to be appalled and entertained simultaneously, pick up a used copy of Graham Greene’s The Comedians, set in Papa Doc’s era. Suffice it to say that it was a time of state-sponsored violence, of the worst order.

Martelly, a known Duvalierist, has stated publicly that he would like to “kill (former President) Aristide and stick a dick up his ass.” (See Jon Lee Anderson’s “Aftershocks” in the New Yorker, February 1, 2016.) The Organization of American States (OAS) and then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton supported him to replace Jude Célestin in the 2011 presidential runoff, which Martelly later “won.”

Really? The Clintons support a guy who talks like this as head of state for a country they claim to respect? So often there is a subtext, an undertone that conveys disparagement of the Haitians, as if they are so “backward,” “undeveloped,” “primitive” that they don’t deserve any better than they get.

As for the situation that has brought us here now, in the recent legislative electoral round held on August 9th apparently there were problems. Lots of them.

My head spins. I lose track of whatever is being said and fall into the daze of watching the ever-shifting panorama outside my window. A tap-tap, gorgeous with its intricate design of orange, yellow and red, stops right in front of us, in the midst of the traffic. So many people emerge that it’s like one of those jokes about how many clowns can fit into a telephone booth. At last a tall and slender older women unbends from the side door.

First comes her cane, feeling out the ground. Next her long limbs unfold. She has on one garment, a plain brown dress that covers her from mid-shin to shoulders. No jewelry or other adornment. She reaches back into the vehicle and pulls out a tall bundle encased in plastic, perhaps a foot in width, improbably curved in the middle, perhaps lessening to about nine inches at the top, perhaps two feet high. This she balances on her head with an unhurried gesture.

At last she walks, using her cane to mediate. No pedestrian lanes, no cuts in a curb in case you need a wheelchair, no curb at all. No driver of course, because no car. Despite her prominent limp she glides to the side of the road in a fluid rhythm. When she arrives at the hodgepodge of dirt and stone, quiet, graceful and serene, very much at ease, she joins the others flowing by. My eyes follow her as she disappears into the crowd. She seems immersed in a quiet joy.

The city thins out and we are on our way to Les Cayes, a town southeast of Port au Prince on the long arm of the country bordered by the Caribbean Sea. The driver is trying to catch up with the caravan of Lavalas’s presidential candidate, Dr. Maryse Narcisse. “Lavalas” means “tide” or “wave” or “flood” in Kréyol.

“Fanmi” means “family.” The symbol on the ballot is one of man, woman and child seated at a table. This symbol is key, both because of the plethora of parties and because many in the impoverished electorate cannot read or write.

We see all this from our van: Garbage—organic, plastic, construction materials, everything—strewn by the side of the road; the sudden appearance of burning garbage right next to the passing vehicles; half-built construction projects now abandoned; others with workers right among everyone else, no hard-hat in sight; streams littered with plastic and who knows what else where women wash the family’s clothes; vehicles spewing black emissions into the air. Little or no infrastructure, no zoning, no safety standards, no way of handling refuse in a healthy manner—there seems to me to be no effective government at all right now in Haiti.

Yet we also experience a beauty during the long drive. Ocean and mountains swing in and out of sight, often both in view at once. The air is warm and soft; the morning contains that fresh human energy that serves as testament to the coming day. Trucks with open backs fill the front window with views of sacks and boxes of goods, women and children inserted in whatever spaces exist on top of and in between. Once I get over the precariousness of it all, I am enchanted with these interior scenes retreating in front of me. So much life tucked into the small moving spaces.

We chat and joke as we trundle along, alternating between near standstill and a reasonable rate of speed on the open road. Dave sings us a song he has composed on a previous trip. The refrain is “Hayi-ti, Hayi-ti, time to get rid of the bourgeoisie…” done in a lovely lilting rhythm. We laugh; we make him do it again and again throughout our short stay.

Hayi-ti. Its Swahili origins mean “do not obey.”

Pierre, raised in Les Cayes, tells us stories and shows us sites from his youth as we finally arrive in his home town. Over there a church of massive stone. The priest who wouldn’t let his mother take communion when the space between her babies got to be too long. Up that street Pierre’s elementary school, now gone. Closed down for one particular election day decades ago, as promised by the Tontons Macoutes. Pierre at eight, delighted to play hooky, so he followed instructions and voted for Papa Doc. Eight times.

Hmmm. Not exactly my idea of happy childhood memories. Yet Pierre’s eyes sparkle and he laughs out loud as he relates them to us. Happy and relaxed, he seems glad to be home. I tell myself to beware of conclusions that life in Haiti is simply grim.

There is lots of action beside us on the road.

All at once we have caught up with the Lavalas procession. Traffic slows to a standstill; people mill about outside the vehicles. A handsome smiling face appears in our side window and the guy turns out to be a Lavalas organizer Margaret knows from a past trip. Delighted, she exits our van to join him.

In the next instant we are all out on the street, mixing with the crowd. I try to find the candidate, to gauge the size of the crowd, to see if I can tell whether the cries and exclamations all come from Lavalas supporters, to ascertain whether this is a big enough throng to win an election amidst a zillion other choices, but mostly I just want to be sure I don’t get separated from my posse. I spy one other white face besides mine and Dave’s, a young woman who sashays past in an angled line going down the street in the opposite direction. She looks like I feel, which is a bit disconcerted at being the tiny minority for once. Yet each time I glance about I see someone I know. I relax, and begin to enjoy myself.

Suddenly a woman in a plain turquoise blouse stands out from the crowd. Dr. Maryse Narcisse. Lavalas’s candidate. If elected, the first freely-elected woman President in Haitian history.

Smiling and at ease, she presses the hands of those around her, including mine, and hugs people, including me. Her gaze is direct; her touch is gentle. She is amazingly accessible despite the men around her for security. The women seem especially enthusiastic as they reach for her, and she for them. Many times throughout this day I spy her in the midst of crowds like this. Intuitively, I trust her.

Eventually we are back in our van, trailing along at the end of the convoy. Margaret’s friend is now with us, and we are four in the middle seat. After a half-hearted offer to be squashed in the way back, instead I am squished toward a central console. Our Lavalas companion hands out business cards with the Fanmi Lavalas logo from the front seat, to people at the side of the road. Often we hear questions called out about “Pe Titid,” or “the little priest,” as Aristide is affectionately named in Kréyol.

Business cards? Could there be a more useless item in an economy where money and food are so scarce that there is a slogan to match vote-buying efforts? “Take the banana, eat the banana, then do what you want,” it is said. In other words, accept their bribes if you are in need, and you will be in need, that’s for sure. Then vote for your true choice.

(The only trouble is that the next day we are told that this time around, the vote buyers are insistent. They escort their marks up to the polling place and watch them cast their votes. So much for the secret ballot.)

So. In and out of the car for the rest of the afternoon. Once in a whole neighborhood dedicated to automobile repair and body work, everything out in the open. Once in a place with a raised stage, which Maryse mounts and descends without giving a speech. Once in a place where a huge truck with a rival candidate and a loud band rolls down the center of the crowded road, with us off to the side. Once to use a much-needed restroom inside a police station where the cops were friendly. Ah, the joy in finding myself in that clean-enough latrine!

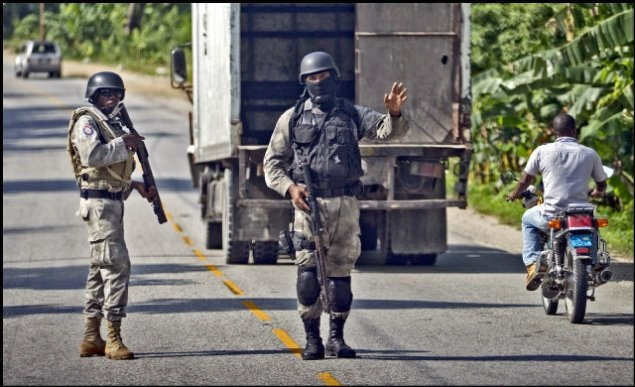

Oh yes, the police. The convoys of soldiers in camouflage gear, jeeps bristling with guns, signs on the side that identify the United Nations occupying force known as MINUSTAH.

The uniformed officers who stop us at road blocks twice, once during daylight and once at night, for no obvious reason but to check the driver’s identification and wave us on.Indeed, the police in all their manifestations appear well-equipped, efficient, functional, unlike the rest of government, which is invisible.

The first of two election workers from the slum outside Port au Prince called Cité Soleil comes into the vehicle to perch on our console and give his report. This tough and wiry guy takes us back to 1804 in his preamble, which, as so often in Haiti, begins with an account of the only successful slave rebellion in history. Per Pierre, this is typical of the knowledge transmitted from parent to child at the evening meal in ordinary homes. This Lavalas worker probably cannot read or write, but he understands more about his country’s history than many of our college graduates. These folks know what they are about. They may be illiterate but they are not dumb. They want a seat at the larger table. Fanmi Lavalas.

The next thing our guest wants to relay is not about August 9th, but about what had happened when Dr. Narcisse toured Cité Soleil a few days before now. He tells us that officers armed with machetes from the Brigade of Operational and Departmental Intervention (BOID), a state-sponsored official elite police force, killed twenty people in one part of Cité de Soleil after Dr. Narcisse left, including two pregnant women. Fourteen more died in a similar fashion in another section (named by others the following day as Wharf Jerémie).

Eventually we do talk about the August 9th election. That was a Sunday, and by the time the elderly people got out of church it was impossible to vote. Some polls were destroyed, or simply closed down. At other locations they told the people who came to vote that they had registered elsewhere. Sometimes the ballot boxes were just stolen outright. So our witness informs us that now there is a new plan for October 25th, also a Sunday. On Saturday night no one will go to bed at all. Instead the people will troop out to the polling places and be there, ready to vote, the minute the polls open.

As Haitians seem wont to do, he invokes a saying: “Saturday will let you know if your Sunday will be beautiful.” Everyone laughs. Haitian or American, poor or middle class, black or white—from our own experience we can all dredge up examples of what that means.

One of us asks how our friend from Cité Soleil feels about a woman being elected to the Presidency. His reply?

“It is time for our President to be a woman. A woman can use 100 gourdes to feed her family one night, and still have some left over the following morning to start a small business.”

Just before this he had been telling us that in Cité Soleil people have been hungry during this time of a terrible economy. “Starvation” was the word translated, as in “there has been much starvation.” 100 gourdes is the equivalent of about $1.70. So a lot of folks don’t even have the $1.70 it takes to feed a family its dinner.

Yet what he has said is funny. To everyone, even to him. We are at the stage of cackles, chortles, guffaws.

Joy infused with sorrow? Sorrow laced with joy? Whatever. Exuberance reigns.

Late afternoon has turned toward evening. Young people dance to a boom box on the side to our right. Behind them are posters that advertise the tourist sector, with Haitian females decked out in tight skimpy clothes that emphasize wide hips and big behinds. Yet I have seen no women in the street actually dressed this way; these women, for example, are enjoying themselves in outfits that are plain, and practical. There it is—that undertone of disrespect for the people.

I have no idea where we are, but Dr. Narcisse is said to be on her way to Jacmel, a city way further up the road, where she means to spend the night. Our plan is to return to our guest house, which already will take us quite a few hours. With the heavy traffic it’s unclear whether or not we are still in the convoy, but we haven’t turned around yet.

Margaret says later that she saw it coming—that a man on a red motorcycle was right beside our vehicle for too long, staring into the van with too much intensity. In any event, suddenly our driver takes a sharp turn and speeds off through side streets. As we careen along, the face of a man clinging to our SUV’s roof appears upside down in the window across from me. Other men run along on both sides, yelling and banging on the van whenever traffic forces us to slow down, or when it seems that we don’t seem to know where to go.

I am afraid. Shouldn’t we offer them money, I ask? Pierre explains quietly. The demand would be endless; everyone out there is hungry; if you give in to one person, it only gets worse. The other two Haitian men in the van, stoic, nod in agreement. I hide my purse under the seat and hold on tight.

We stop at one point, and Margaret’s Haitian friend gets out from the front passenger side, steps back toward the crowd and yells directly in the faces of those accosting us. Whatever he says in Kréyol has an effect, because the group backs off for a second. Enough time for him to hop back in, the driver to take off, and the chase to begin again.

Now it seems that the guy clinging to our roof—the same one from the beginning—is on our side, and guiding us to safety out of the maze of streets. Maybe we have even given him money for this, but if so, I have no idea of when or how that happened.

Finally, after what seems like an hour, but is probably no more than ten minutes, we pull into a gas station. Shell, I believe. There a man stands with an enormous gun, and all at once, everyone else is gone, including our friend on the top.

Joy? Are you kidding me? But there is an immediate flood of it, contained in the supreme relief of feeling safe. I claim to hate guns, to despise male-enforced violence, and trust me, I am not going to change my mind on this. Thus my joy here violates my own principles, to the point where it makes me laugh out loud as I imagine how I will describe this if and when I ever get back home.

In the meantime, down the darkened walkway in the back it is said that there is a bathroom. I use my cell phone flashlight to find it. Relief. No toilet paper but lo, the experienced traveler is supremely prepared. Back up the path there is a dimly lit patio, a bar that appears to offer beer and wine at least. And food, as it turns out, from a kitchen within. We decide to settle in, to eat and drink. The nervous system calms a bit.

The beer refreshes. The food is truly delicious. The whole thing for the eight of us, including the driver, costs about thirty-five bucks, so it is easy to be generous and pay. Ah yes, that lovely exchange rate, so beneficial for foreigners. Satisfaction. Another form of joy.

After all that, the long long drive home is almost relaxing. To my relief my final offer to squeeze into the back is turned down yet again, and once more I am in the middle, pushed to the very edge of the seat. I stretch a stiff knee onto the console and settle in to watch the road. Late at night the trucks are larger, their backs still open, the space inside a couple of stories high. Again there are human beings nestled in among the stacks of goods—this time exclusively men and boys.

Margaret asks if we want music. What a notion! Pierre requests “The House With The Rising Sun,” by some group I never heard of. She punches it into her phone, buys it on the spot and miraculously we are listening to the song he has asked for.

I am the type who cannot stop talking about the chase. The Haitian men chuckle, and one comments that in Haiti it’s best not even to show excitement, let alone fear. Again the explanation of the level of extreme need out there. They act as if this kind of occurrence is common, normal, just part of how things are.

Whole areas go by with no electric lights, just faint kerosene glows from inside some of the homes. We are happy.

When we finally get back to Port au Prince, as we drop each companion off he rings or knocks at a closed gate in a high wall, and we wait to see that he gets in all right. It is 3 AM when at last we pull into our own guest house’s courtyard. The hostess’s husband answers the front door at once. Happy and relieved, he takes his wife’s hand and leads us all inside. “Home” and in bed at last, I surprise myself, and sleep.

The next day by noon we are at Lavalas headquarters in Port au Prince, listening to more stories. The coordinator in Archaie, a department of the country that includes the mountains north of Port au Prince and the historic city of Fond Baptiste, describes in detail how during the prelude to August 9th BOID members, dressed in blue and sometimes masked, chased people, burned twenty of their motor bikes, broke into their stands, stole their cash, “disappeared” individuals, wounded two in a popular demonstration the day before the election (who later died and were buried in the woods) gassed a little kid who happened to be on the way to school (who also died later). On and on. Out of fourteen voting centers Archaie, only four actually functioned through election day.

A Port au Prince mayoral candidate says of the neighborhood of Bellaire on August 9th—“call it anything, but not an election. “ He repeats what has become a familiar refrain: Armed members of BOID, with the complicity of local police, destroyed ballots to make sure votes weren’t counted in Lavalas strongholds. The mayor of Bellaire himself tells us that people with guns destroyed whole voting centers there.

The tales proliferate. People with guns tore down Lavalas posters. Lavalas workers were physically attacked as they tried to educate people about the mechanism of casting a vote. Accounts of open vote-buying; sending registered voters from place to place to search for their names on an ephemeral list, with no provision for casting a provisional ballot; confusion re who among the multitude of parties was allowed to have observers at a particular polling place and time.

And destruction of ballot-boxes in a planned and determined fashion that takes a while to explain. Apparently the polling places often had several spots for casting votes at each location. A particular spot was to tally 450 votes, and then to close down. But after one party (hmm, I wonder which one that might be…) got 200, all those votes were sometimes thrown out, and no more allowed to be cast.

A spokesman for a grassroots organization points out that at the last Presidential election, when Lavalas was not allowed to participate, 300,000 chose the President out of 4,700,000 eligible to vote. These tactics all seem designed to cause “low voter turnout,” so beware when the phrase is used to describe a Haitian election, I instruct myself. Yet another example of that disrespect for the Haitian people.

Another guy describes BOID as worse than the Tonton Macoute. Difficult to imagine, but maybe true?

No joy in these stories. None.

But the folks who have gathered around a huge table to tell us all this are working on an election after all, and they have been talking with us for a couple of hours by now, so they have to get back to it.

As for us, we schedule a press conference for the next morning. And despite computer glitches, cell phones that don’t work and last-minute requests for money to help with transportation and equipment, the word does get out, and quite a few press people actually show up. Reporters drift in throughout the allotted two hours. Some are young women; some take photos; some record videos; all listen intently as we begin again, over and over, to accommodate the new arrivals. We are exhausted. We have a plane to catch.

Given that everything takes longer than expected, I am dismayed to find that an unexpected final meeting is being inserted into our schedule. This time with port workers. They are right on the way to the airport, Pierre assures me. A crowd gathers around us when we arrive. Young and old, the work has taken its toll on everyone’s bodies. There is no shelter from the brutal sun while they wait for their assignments, the people tell us. And in fact I am, sweating. And we have no water to drink during the work day, they add.

Our group has no answer for this. And except for the fact that if Lavalas came to power it would be with the goal of changing the system that works to keep people this poor, the meeting has no direct connection to the election. I dream of us raising money when we get home, just for this one thing. I say it to Pierre, who humors me.

We are told that it matters to people to have an account of their suffering heard by the outside world. Will this relieve a bit of the pain of the port workers’ hard lives? And if so, can that relief be called joy?

Eventually we arrive at the place to turn in the rental van, which takes forever, to wait through three separate security lines at the airport, which takes forever, to purchase duty-free Haitian Barbencourt rum, which takes forever, and to find ourselves on the bubble of privilege called an airplane.

Joy in the cessation of things to do, joy in the peace high up in the air, joy in the snack provided for the short flight. Joy even in missing a connection in Fort Lauderdale, since the airline has to pay for a hotel and food. Joy in a gin and tonic, in a seafood plate so large I waste most of it. Joy in finally getting home. Joy in drinking the Barbancourt later with family and friends. Joy in the resumption of my so-much-easier life.

And the election?

Predictably, October 25th is a giant mess. For days there is no news at all of the results, and when it does come, the Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) publishes figures that conclude that Dr. Narcisse from Lavalas got 7.05% of the vote.

7.05%?? Why ban a party for ten years if its level of support is that pathetic? I might have wondered if the report was 43.2%, or even 36.5%. But 7.05%? No. I don’t believe that.

Martelly’s choice, Jovenal Moïse, is declared the winner. No surprise there. Jude Célestin is announced as second in a runoff scheduled for December 29th. He has been through this before, remember? He declares that the whole process is fraudulent and refuses to participate in any runoff.

Mass demonstrations in the streets force the cancellation of the December 29th runoff, and then of two more runoffs scheduled in January, 2016.

On February 7th, 2016, Michel Martelly, his term up, leaves his office under pressure. An agreement has been reached which provides for an interim “President,” chosen by the legislature that was “elected” on August 9th. In a meeting that lasts all night, the legislature chooses a guy named Jocelerme Privert for the interim period. Privert, needless to say a controversial pick, is the first Haitian President in history to be selected by a legislative body. The plan is for him to serve for up to 120 days, during which an election of some sort will be held on April 24th, with the final head of state to be installed on May 14th.

Six of the CEP’s nine members have resigned.

Lavalas is formally contesting the October 25th election, and will settle for nothing less than starting over, with a process that is fair from the beginning, to elect a President for Haiti.

I find it difficult to end this piece. When I think of Haiti I wince. The sadness there makes people turn away. I want to turn away. And I don’t want to squeeze the material for a phony optimism.

But then I remember the Cité Soleil organizer’s determined narrative that begin in 1804, with the victory of the world’s one and only successful slave rebellion. If this guy can laugh about how a woman has to squeeze the worthless Haitian gourde to feed her family, then I can laugh too.

If Pierre can be so happy to return to the city of his youth, then I can look at the scenes passing by our van’s window with curiosity instead of disapproval.

If our calm Haitian friends can attribute the attempted shakedown to the people’s desperate need instead of depravity, then I can be courageous and compassionate as well.

If the Haitian people can find meaning in all this hardship through their resilience and determination, their refusal to endure the terms of modern economic slavery, then from my luxurious first world perch, well, so can I.

If the elderly woman who got out of the fabulous gaudy tap-tap can move with grace and dignity among her fellow citizens, then surely I can take her as my model. I can make my way through remembering this experience on the page not with despair, not plagued by fear, but with joy.

Go to Original – barbararhine.wordpress.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: