Nuclear Security: Continuous Improvement or Dangerous Decline?

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, 4 Apr 2016

Matthew Bunn, Martin B. Malin, Nickolas Roth and William Tobey - Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

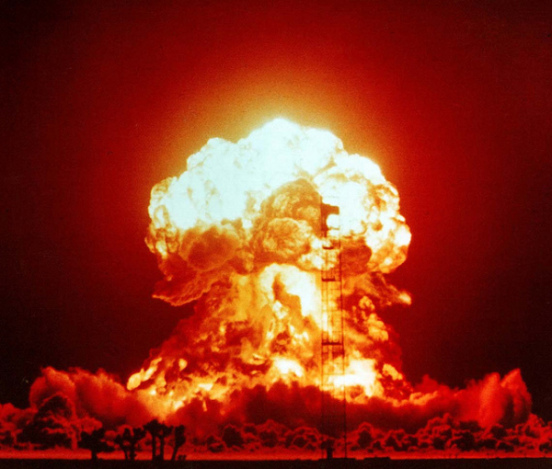

Image by the Official Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) Photostream – flickr.com

27 Mar 2016 – World leaders face a stark choice at the final Nuclear Security Summit later this week: Will they commit to efforts that continue to improve security for nuclear weapons, fissile materials, and nuclear facilities, or will the 2016 summit be seen in retrospect as the point at which attention drifted elsewhere, and nuclear security stalled and began to decline? The answer will shape the chances that terrorist groups, including the Islamic State, could get their hands on the materials they need to build a crude nuclear bomb.

In a report (pdf file) we published late in March, we outline the shape of the threat and the steps that must be taken to keep potential nuclear bomb material out of terrorist hands.

The world has made a lot of progress in securing vulnerable nuclear weapons-usable material:

- More than half of the countries—30 of 57—that have had weapons-usable nuclear material on their soil eliminated it, in nearly all cases with US help.

- Security for nuclear weapons and materials at scores of sites around the world has been dramatically improved. Essentially every country that still has nuclear weapons or weapons-usable nuclear materials has tightened its security requirements over the past two decades.

- At the 2014 nuclear security summit, 35 states joined together in a “strengthening nuclear security implementation” initiative, in which they pledged to meet the objectives of International Atomic Energy Agency security recommendations and accept regular reviews of their nuclear security arrangements. In 2016, Jordan joined the initiative.

- Since reactor conversion efforts began in 1978, 65 highly enriched uranium-fueled research reactors have converted to low-enriched fuel, and well over 100 have shut down.

- As of March 2016, only eight more countries need to ratify the 2005 amendment to the physical protection convention before it goes into force (although it has been 18 years since it was first proposed).

But a global “reality check” on the status these efforts reveals that there’s a lot more to be done.

Since the 2014 Nuclear Security Summit, there has only been modest progress securing vulnerable nuclear-weapons useable material around the globe, and some efforts have lost ground. At the end of 2014, Russia cut off most nuclear security cooperation with the United States. The Obama administration is proposing its lowest-ever budget for programs to improve nuclear security around the world. Fewer countries are announcing major security improvements at nuclear facilities, and some are hanging on to highly enriched uranium or plutonium stocks they clearly do not need. And, the Nuclear Security Summit process is coming to an end—potentially decreasing international attention to this issue.

Meanwhile, threats are constantly evolving, and there are new, worrying trends. Two years ago, the Islamic State was one of many small extremist groups. Today, it controls swaths of Iraq and Syria, is recruiting globally, has demonstrated a desire and capability to strike far beyond its borders, and espouses apocalyptic rhetoric. And incidents such as an IS operative’s intensive monitoring of a senior official of a Belgian facility with significant stocks of HEU highlight the continuing threat.

Since the last Nuclear Security Summit, security for nuclear materials has improved modestly—but the capabilities of some terrorist groups, particularly the Islamic State, have grown dramatically, suggesting that in the net, the risk of nuclear terrorism may have increased.

We offer several recommendations to get nuclear security on the path of continuous improvement:

- All countries and organizations that handle nuclear weapons, highly enriched uranium, and plutonium need to commit to provide effective and sustainable protection for these stocks against the full range of plausible adversary threats—and provide adequate resources to fulfill that commitment.

- The United States and Russia should rebuild their nuclear cooperation based on a new, equal approach, drawing ideas and resources from both sides and including both nuclear energy and nuclear security initiatives.

- The United States should seek to expand nuclear security cooperation with Pakistan, India, and China, and undertake nuclear security discussions and good practice exchanges with all of the countries where nuclear weapons or weapons-usable materials exist.

- The United States and other interested countries should take a broader approach to consolidating nuclear weapons and materials at fewer locations around the globe, addressing plutonium as well as highly enriched uranium and both military and civilian material. These countries should offer incentives to shut down unneeded facilities and help convert them to use fuels that cannot be made into a nuclear bomb.

- In the absence of Nuclear Security Summits, senior officials of interested countries should continue to meet to oversee implementation of existing nuclear security commitments and suggest ideas for additional steps.

- Interested countries should develop approaches for building real confidence that effective nuclear security measures are in place without unduly compromising sensitive information.

Effective and sustainable nuclear security is the single most effective means of preventing terrorists from acquiring a nuclear weapon. Now is the time for world leaders to put the world on the path toward continuous improvement in nuclear security.

___________________________________

Matthew Bunn is a professor of practice at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. Before joining the Kennedy School, he served for three years as an adviser to the Office of Science and Technology Policy, where he played a major role in US policies related to the control and disposition of weapons-usable nuclear materials in the United States and the former Soviet Union.

Martin B. Malin is the executive director of the Project on Managing the Atom at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. His research focuses on arms control and nonproliferation in the Middle East, US nonproliferation and counterproliferation strategies, and securing nuclear weapons and materials.

Nickolas Roth is a research associate at the Belfer Center’s Project on Managing the Atom. Before Harvard, he spent a decade in Washington, D.C., where his work focused on improving government accountability and project management, arms control, and nonproliferation. Roth has written dozens of articles on nuclear security, nonproliferation, and arms control.

William Tobey is a senior fellow at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. He was most recently deputy administrator for defense nuclear nonproliferation at the National Nuclear Security Administration. There, he managed the US government’s largest program to prevent nuclear proliferation and terrorism by detecting, securing, and disposing of dangerous nuclear material.

Go to Original – thebulletin.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION: