How Leo Tolstoy Found His Purpose: The Beloved Author on Personal Growth and the Meaning of Human Existence

SPIRITUALITY, 23 May 2016

Maria Popova | Brain Pickings – TRANSCEND Media Service

“That which one has set oneself to do, one should not relinquish on the grounds of absence of mind or distraction.”

“To be a moral human being is to pay, be obliged to pay, certain kinds of attention,” Susan Sontag asserted in one of her final works, a superb meditation on storytelling and what it means to be a good human being. Perhaps the most important kind of attention required is to our interior life and the values we allow to animate it, which become the scaffolding of our spirit and our wayfinding tool for navigate life. “There may be moments in life when we are so unformed that we need to use values like an exoskeleton to keep us from collapsing,” Parker Palmer wrote in his masterwork on discerning one’s path.

“To be a moral human being is to pay, be obliged to pay, certain kinds of attention,” Susan Sontag asserted in one of her final works, a superb meditation on storytelling and what it means to be a good human being. Perhaps the most important kind of attention required is to our interior life and the values we allow to animate it, which become the scaffolding of our spirit and our wayfinding tool for navigate life. “There may be moments in life when we are so unformed that we need to use values like an exoskeleton to keep us from collapsing,” Parker Palmer wrote in his masterwork on discerning one’s path.

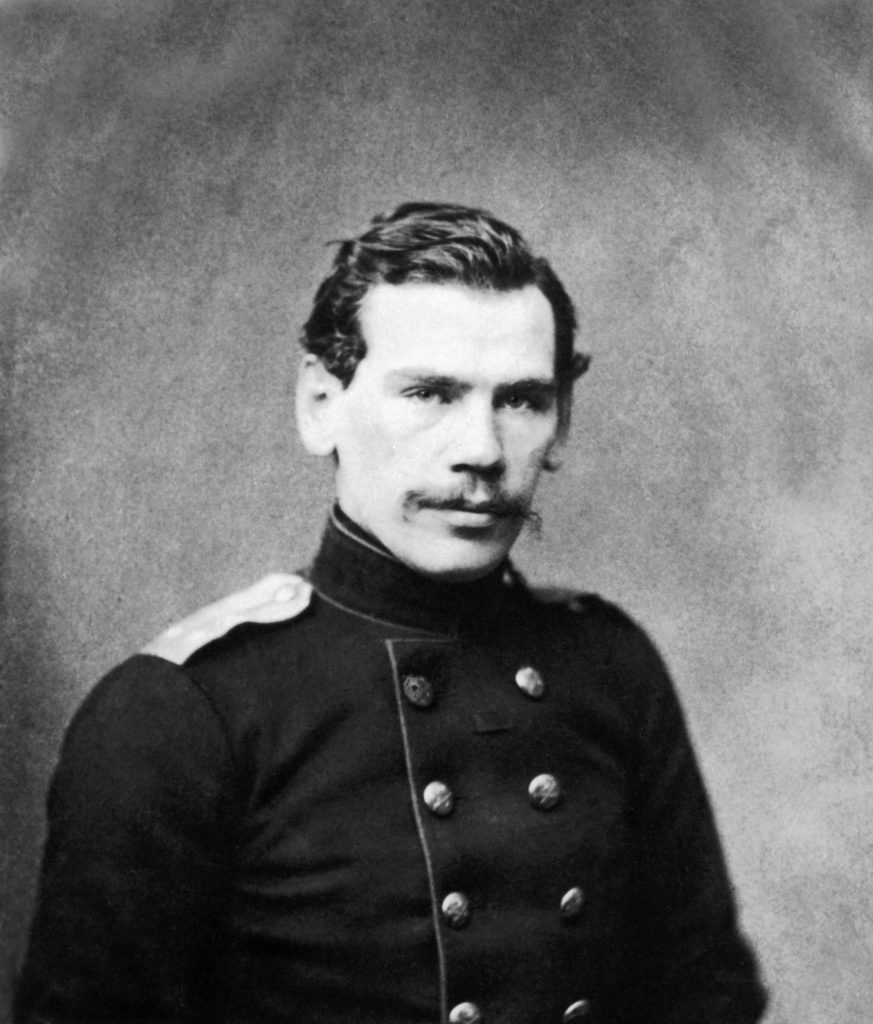

As he struggled to find his purpose in life, young Leo Tolstoy (September 9, 1828–November 10, 1910) sketched the construction of that exoskeleton in The Diaries Of Leo Tolstoy: Youth (public library | free ebook) — the remarkable record of his moral and spiritual development.

In an entry from April of 1847, 21-year-old Tolstoy writes:

I keep finding myself confronted with the question, “What is the aim of man’s life?” and, no matter what result my reflections reach, no matter what I take to be life’s source, I invariably arrive at the conclusion that the purpose of our human existence is to afford a maximum of help towards the universal development of everything that exists.

If I meditate as I contemplate nature, I perceive everything in nature to be in constant process of development, and each of nature’s constituent portions to be unconsciously contributing towards the development of others. But man is, though a like portion of nature, a portion gifted with consciousness, and therefore bound, like the other portions, to make conscious use of his spiritual faculties in striving for the development of everything existent.

If I meditate as I contemplate history, I perceive the whole human race to be for ever aspiring towards the same end.

If I meditate on reason, if I pass in review man’s spiritual faculties, I find the soul of every man to have in it the same unconscious aspiration, the same imperative demand of the spirit.

If I meditate with an eye upon the history of philosophy, I find everywhere, and always, men to have arrived at the conclusion that the aim of human life is the universal development of humanity.

If I meditate with an eye upon theology, I find almost every nation to be cognizant of a perfect existence towards which it is the aim of mankind to aspire.

So I too shall be safe in taking for the aim of my existence a conscious striving for the universal development of everything existent. I should be the unhappiest of mortals if I could not find a purpose for my life, and a purpose at once universal and useful… Wherefore henceforth all my life must be a constant, active striving for that one purpose.

In the fashion of young men from that era, who drafted lists of their personal rules of conduct in their journals — a practice popularized by Benjamin Franklin and perfected by André Gide — young Tolstoy writes a few days later:

One of my general rules: That which one has set oneself to do, one should not relinquish on the grounds of absence of mind or distraction, but, on the contrary, take in hand for the sake of appearances. Thoughts will then result.

Although he would later come to lament the questionable motives behind his early foray into writing, the next five years were both tremendously trying — like Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy succumbed to gambling and spiraled into debt — and a major creative growth spurt that led to his debut as a writer. But he remained existentially restless. In a diary entry penned shortly before his thirty-fourth birthday, Tolstoy contemplates his life’s purpose with growing anxiety:

For some time past I have been tormented with regret at having wasted the best years of my life. It dates from the time when I began to feel myself capable of doing something good. Interesting it would be to describe the course of my moral growth; but neither words nor thoughts would be sufficient for the purpose.

To great thoughts there are no boundaries: yet long ago writers reached the impassable boundary of the expression of such thoughts. Played a game of chess, had supper, and now am going to bed. The pettiness of the life worries me. True, I feel this because I myself am petty ; but in me I have the capacity to despise myself and my life. There is something in me which forces me to believe that I was not born to be what other men are… I am grown to maturity, and the season of development is going, or gone, and I am tortured with a hunger … not for fame — I have no desire for fame; I despise it — but for acquiring great influence in the direction of the happiness and benefit of humanity.

Shall I die with the wish a hopeless one?

[…]

I fear vanity so much, and so much despise it, that I do not expect the satisfaction of it to afford me pleasure. Yet this is all that I have to look to, since, otherwise,

what would remain as a starting-point? Love and friendship … have they brought me happiness? Or is it that I have been unfortunate? Solely upon this hope rests any desire of mine to live and strive. If happiness and useful activity be possible, and I test them, I shall at least be in a position to put them to the best use. O Lord, have mercy upon me!

That year, Tolstoy made his literary debut with Childhood — the first volume of his autobiographical trilogy — and so began his self-made destiny as one of humanity’s most visionary and life-giving voices. Throughout his long life, despite his often debilitating fallibility and the major existential crisis of his middle age, he never lost sight of this sense of purpose and remained animated by his youth’s desire to advance “the universal development of humanity” until his final breath.

Complement this particular portion of The Diaries Of Leo Tolstoy: Youth with Richard Feynman on the meaning of life, the story of how Van Gogh found his purpose, and contemporary soul-bolsterer Parker Palmer on how to let your life speak, then revisit Tolstoy on what separates good art from the bad, why we drink and party, his forgotten correspondence with Gandhi about violence, human nature, and why we hurt each other, and his reading list of essential books for every stage of life.

______________________________________

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors.

Go to Original – brainpickings.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.