The TTIPing Point: Protests Threaten Trans-Atlantic Trade Deal

TRADE, 16 May 2016

Dinah Deckstein, Simone Salden and Michaela Schießl – Der Spiegel

An unprecedented protest movement of a scope not seen since the Iraq war in Germany has pushed negotiations over the TTIP trans-Atlantic free trade agreement to the brink of collapse. The demonstrations are characterized by a level of professionalism not previously seen.

Last week’s TTIP Leaks and a growing movement against the free trade agreement is threatening the trans-Atlantic deal. A quarter of a million people even turned out in Berlin for a mass protest against it in October. The protest movement in Germany now has a new face — one filled with well-educated people.

DPA

6 May 2016 – As the battle over TTIP was lost, Angela Merkel feigned resolution yet one more time. “We consider a swift conclusion to this ambitious deal to be very important,” her spokesperson said on her behalf on Monday. And this is the government’s unanimous opinion.

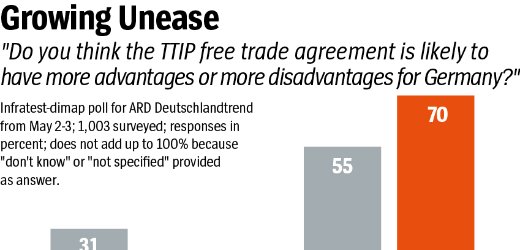

But the German population has a very different one. More than two-thirds of Germans reject the planned trans-Atlantic free trade agreement. And even in circles within Merkel’s cabinet, the belief that TTIP will ever become a reality in its currently planned form is disappearing.

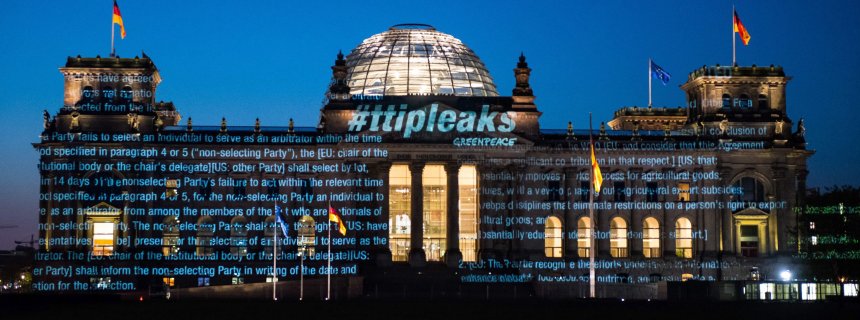

That’s because on Monday morning, Greenpeace published classified documents from the closed-door negotiations. Even if the papers only convey the current state of negotiations and do not document the end results, they still confirm the worst suspicions of critics of TTIP.

The 248 pages show that bargaining is taking place behind the scenes, even in areas which the EU and the German government have constantly maintained were sacrosanct. These include standards on the environment and consumer protection; the precautionary principle, a stricter EU policy that sets high hurdles for potentially dangerous products; the legislative self-determination of the countries involved, etc. Even the pledge made on the European side that there would be no arbitration courts has turned out to be wishful thinking. So far, the Americans have insisted on the old style of arbitration court.

The result is that Merkel’s grandly staged meeting with US President Barack Obama in Hanover eight days earlier had been nothing more than a show — one aimed at hiding the fact that the two sides are anything but united in their positions.

The leaks have resulted in a failed attempt to bypass 800 million European citizens as they negotiate the world’s largest bilateral free trade agreement. From the very beginning, the government underestimated the level of resistance these incursions on virtually all aspects of life would unleash among the people.

What began as a diffuse discomfort over opaque backroom dealings grew into a true public initiative, especially in Germany. It was fueled by an international alliance of non-government organizations that has acted in a more professional and networked way than anything that has come before.

TTIP Protests a Part of Everyday Life

Three years after the beginning of negotiations, events protesting free trade agreements have become part of everyday life in Germany. In cities and towns, thousands of events are being held to express opposition to deals like TTIP, CETA, as the recently negotiated agreement with Canada is called, and TISA, an international deal covering trade in services.

Here’s a sample of what this looks like in just a few places. In the city of Mainz, 150 orchestra musicians play the protest song “We’re not Merchandise,” a reworked version of Ludwig von Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” In Darmstadt south of Frankfurt, 230 people in a packed hall grill candidates in the local election on the issue of free trade. Meanwhile, in Cologne, where there are traditional “dance into May” celebrations marking the arrival of May 1, a “Dance against TTIP” was even held.

In Bergisch Gladbach, a town located near Cologne, the city council approved a resolution opposing TTIP and CETA. A total of 310 cities, municipalities, counties, districts and regions have registered themselves with the Munich Environmental Institute as TTIP-free zones.

So what is prompting thousands of people to use their spare time to study up on such complicated material as a free trade agreement? Or to voluntarily participate in workshops and discussions addressing the incomprehensible legalese used by the EU in such documents? Or to travel hundreds of kilometers to attend a protest?

Anyone seeking to better understand how Germany’s protest culture has changed in recent years need only travel to the city of Münster. A room on the first floor of the Institute for Theology and Politics is full of dusty devotional objects commemorating protests of the past. There’s a quote on the wall from Nelson Mandela as well as a Cuban flag; and on the shelf there’s a yellowing binder with the words “Nicaragua 1979-1991” on it.

A New Protest Culture

On the first and third Tuesday of each month, the group Münster against TTIP meets here. Its members include people like Ute S., a 67-year-old retiree who worked as a civil servant for the federal government. These days, she spends about two hours a day surfing social networks and online publications for new information about CETA and TTIP. Or people like Stefanie Tegeler, 36, a political scientist, who says, “I have nothing against free trade, but I do have a fundamental problem with a lack of transparency.” And people like Michael Beier, 49, a marketing expert who says: “I was never a political person, but I have found my movement here.”

At this particular meeting, the group discusses the most recent TTIP protest in Hanover. Over 150 group members traveled on three buses to the protest, and most had never even attended one of the Tuesday meetings. “When they’re needed, though, the people come,” says Beier, “because they understand that TTIP is something that impacts all of us.”

The new quality of the protests against TTIP has also turned marketing man Beier into an activist. Beier is pleading with people to leave their stage wagons and microphones at home. He says this is about keeping people on equal footing. “The people don’t need show-masters anymore.”

Thirty-five-year-old Jörg Rostek, who is typing the minutes from the meeting into his laptop, says, “What we are witnessing here is a new protest culture that is different from all the time-honored rituals.”

Rostek is one of the founding members of Münster against TTIP, but he has also been active with the Green Party. He says that local politicians “have little time to delve into issues like TTIP,” and that these gaps are now being filled by local initiatives. “We are thinking here in big contexts, we’re working our way through highly complex circumstances, we’re reading hundreds of pages and we’re seeking out experts who can classify and explain things,” says Rostek.

‘Not Worthy of a Democracy’

Rostek says it’s important for him to emphasize that he and the others at the table “aren’t just against it.” And he says they’re not just fighting against the four letters, “but rather to ensure that democracy and European values survive.” In that sense, the fight against CETA and TTIP also has nothing to do with unvarnished anti-Americanism, adds Stefanie Tegeler, who says that such sentiment isn’t prevalent among her generation, anyway. “At the end of the day, the Canadian and American people are also fighting for the same rights,” she says. “If we shared our knowledge, we could learn from each other.”

At the same time, at the other end of Germany, Greenpeace is going public with leaked documents from the secret TTIP negotiations. They make a huge splash in the country and leave many asking if the trade deal is now doomed. Late that afternoon, representatives of the non-government organization Mehr Demokratie, or Greater Democracy, a national group that advocates for an increase in the number of referendums held in Germany, hold a meeting in Munich. They want to hand out flyers at a village festival and also try to gain supporters for a referendum against CETA that is scheduled in Bavaria. The EU is planning to implement parts of the agreement even before national parliaments are provided with the opportunity to vote on it.

The German government’s secrecy in its TTIP dealings is “not worthy of a democracy,” says businesswoman Brigitte Grübler, 46. She’s been joined at the meeting by the CEO of a mid-sized company as well as a former top Siemens executive.

A large share of the recruits to the anti-TTIP movement come from the more educated parts of society, as indicated by a survey conducted by TNS Enmid, one of Germany’s leading pollsters. These aren’t professional troublemakers — they’re people who don’t like to be taken for idiots. “The government has been withholding essential information,” one of them chides. “I never would have been allowed to do that in my previous position as an executive.”

Bavarian Finance Minister Markus Söder barely has a chance to enter into the festival tent before a flyer is passed into his hands. The politician with the conservative Christian Social Union party smiles amiably. Even the police attempt to be as polite as possible to the protesters. “If you need anything, just get in touch with us,” the officer leading the police tells the protesters. “Good luck.”

Broad Opposition

The police’s own union has even joined forces in the protests against free trade, as has every other union that is a member of the German Trade Union Confederation (DGB). They aren’t alone. They are joined by the social welfare organization Paritätische Wohlfahrtsverband. The German Cultural Council. Environmentalist organizations like BUND, NABU, WWF, NaturFreunde, the Environmental Institute and Greenpeace. Development organizations Bread for the World and Oxfam. Organizations critical of globalization like Attac, the citizen movement Campact, the consumer protection group Foodwatch, the German small farmers association and Mehr Demokratie.

In October, they all joined forces to hold a protest against TTIP and CETA in Berlin that drew people from all across the country. Some of the partners on the national level were even instigated by Economics Minister Sigmar Gabriel.

In order to counter claims of a lack of transparency in the trade negotiations, Gabriel invited representatives of major institutions to join a TTIP advisory board. But it didn’t take long for disputes to emerge. The officials on the board complained that the Economics Ministry was largely representing the EU position and that critical voices were being brushed over. Slowly, those voices began to get louder — representatives of the church exposed problems TTIP would create for fair trade, unions expressed concern about its impact on the working world and the head of the consumer advice center pointed to problems with food standards. “Until then, people had just been focusing on their individual issues. But now it was clear how many areas of life TTIP would permeate,” says one member of the advisory board. A good number of those members then joined the anti-TTIP movement.

Around 250,000 people traveled to Berlin for the mass demonstration in what was the largest protest in Germany since the marches against the Iraq war in 2003.

Disparaging a Movement

From the very beginning, politicians with both parties in the German coalition government — the conservatives with the Christian Democrats and the center-left Social Democrats — sought to disparage the movement. In a debate about TTIP in the federal parliament, the Bundestag, CDU member Andrea Lämmel said, tersely, “We know how signatures are collected on the streets.” Fellow party member Joachim Pfeiffer referred to the citizen movement Campact as being part of an “outrage industry.” Those who have decided to hitch themselves to the cart of Campact, Attac and Foodwatch, are “simply constructed,” Pfeiffer claimed.

The organization Lobbycontrol noted that media coverage of the protests had been oddly unbalanced, alleging that many news organizations sought to portray the peaceful protests in ways that somehow put them on the level of the anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant Pegida marches.

But none of the labels stuck — neither the claims of ties to Pegida nor the suggestions by politicians and the business community that TTIP opponents were either notoriously anti-trade, anti-globalization, hysterical scaremongers or anti-American. Support among the American and German populations for TTIP has dropped considerably over the past two years before recently falling off the deep end.

Proponents argue that this is due to their opponents’ efforts to make the debate an ideological one. “Organizations like Foodwatch and Campact are nothing more than professional protest companies that make money off people’s fears and don’t provide any factual input in the public debate about the TTIP,” complains CDU politician Pfeiffer.

A New Kind of Movement

As it turns out, the opposite is true. The growth of the anti-TTIP side has a lot to do with their use of arguments that are supported by studies or external expertise, which TTIP supporters have not been able to contradict.

The success of the TTIP opponents is closely tied to the professionalization of non-governmental organizations. NGOs like Greenpeace, Campact and Foodwatch have competent staffs and more than enough resources to order counter-assessments, hire experts, carry out actions. Their experts can analyze complicated trade papers and translate them into language that a lay person can understand. They are networked to one another, even internationally, and are adept at using social media. They force the release of information about laws and supply the public with internal documents whilst TTIP supporters insist on the confidentiality of the negotiations.

The fight against TTIP began with Pia Eberhardt. The Cologne resident works for the Brussels-based NGO Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), a group that monitors lobbyists. The economist had already gained some experience examining international arbitrage during her studies, so she took on the planned mechanism in the TTIP. When she discovered the powerful possibilities for legal action by businesses against states that it contained, she wrote a report and tried to establish contact with journalists. CEO simultaneously discovered that the European Commission in Brussels had eagerly met with business representatives in advance of the TTIP but not with representatives of civil society. The first big issues with the TTIP had been found: A lack of transparency, the prioritization of business and the establishment of parallel standards of justice.

German organizations quickly adopted the issue. In the spring of 2013, even before the European Council, the powerful EU body representing the leaders of the 28 member states, adopted the negotiating mandate for TTIP, the first NGOs signed onto TTIP Non-Negotiable network, an umbrella organization comprised of over 60 groups.

Neither the business nor the political world noticed what was brewing. It had been a long time since trade policy had been a major topic for NGOs. But when it became clear that the US-Europe pact would exceed the framework set by all previous agreements, that changed.

‘In the US There Has to be a Corpse’

Thilo Bode, founder of the consumer protection agency Foodwatch and a former head of Greenpeace, didn’t want to have anything to do with TTIP at first. But more and more sponsoring members pushed him to take it on. They wanted to know if European food sector standards were imperiled by TTIP. Bode read up on the subject and soon discovered the fundamental contradiction between the European precautionary principle and the aftercare principle. “In Europe, nothing is allowed that is suspected of being hazardous to people’s health,” he says. “In the US, there has to be a corpse, then things are regulated by litigation.” The next big TTIP subject was born.

Experienced campaigner Bode was hooked. In 2015, his book, “Die Freihandelslüge” (The Free-Trade Lie) became a bestseller. In it, Bode describes how political policy becomes subordinate to business interests and how the business world can use the so-called instrument of regulatory cooperation to intervene in legislation. “The book fell on fertile ground, because citizens continue to feel powerless, continually have less of a say and are bamboozled again and again,” says Bode. The recent revelations only fuel that impression further: “In my already long career as an ‘activist,’ I have never experienced a political project in whose defense the government and the ministries have lied to us so unwaveringly and brazenly and so one-sidedly taken up the side of the corporations.”

Greenpeace has been actively addressing the subject of trade since 1990. Their expert, Jürgen Knirsch, remembers with great fondness the two crates containing “Practice Safe Trade” condoms that he had to smuggle into the negotiation building during the world trade talks in Seattle. In the riots that happened there, he met the Harvard legal expert Lori Wallach, who is currently organizing the resistance against the TTIP in the US as part of her work for the citizens’ protection organization Public Citizen. Knirch is well connected with the NGOs that focus on trade. “There is not a lot of competition between us, we exchange with each other and work together.” The pooling of resources and splitting of work is another key element of the movement against TTIP.

Greenpeace is known for creating campaigns that are very media savvy, but nobody can mobilize people these days better than the citizen movement Campact. On their internet platform, people can start petitions or sign ones, and thus take their first step towards being politically active. With short explainer videos and jazzy calls to action it manages to bring even difficult subjects to people’s attention. Campact also tries to get signatories to take action. Campact is the most powerful arm of the movement, this is where protests and protest materials are prepared. During the last elections for the European Parliament, they distributed 6.5 million fliers on voters’ doors.

False Promises

“At first, TTIP was sold to us as providing growth and jobs,” says spokesperson Jörg Haas. But this claim by proponents has been exposed piece by piece as fully over-exaggerated: The most optimistic studies by proponents predict a modest growth rate of 0.5 percent over a space of 10 years — those are just five thousandths per year. “The TTIP leaks have now also dismantled the second story: that TTIP would establish high standards,” Haas says.

The EU and the Federation of German Industries (BDI) first had to correct their growth predictions downward. Tufts University in Massachusetts had presented research in 2014 that a post-TTIP Europe would lose about 600,000 jobs by 2025 and — depending on the country — lead to a loss in personal income of between 165 and 5,500.

Global Justice Now, a TTIP opponent group, recently used the Freedom of Information Act in the United Kingdom to force the release of one of the reports commissioned by the government there, which has been kept under wraps since 2013. In the report, researchers from the London School of Economics argued that the agreement contained many risks and brought few to no advantages. Prime Minister David Cameron held this devastating result secret — and instead promoted TTIP to his citizens.

The Controversy Will Stay

It’s hard to know what drives politicians to sell out their people and their country. What’s sure is that, while the politicians in charge may come and go, TTIP would remain for decades. International treaties are very hard to rescind.

But EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström still wants to go through one or two rounds of negotiations with the US before drawing a summary. Observers assume that the ultimate outcome will be a “TTIP Light,” containing only the noncontroversial points, in order to save face for all of the people involved.

At the same time, a complete cancelling of the agreement is not out of the question either. “A world without TTIP is possible,” says Bernd Lange, a member of the Social Democrats and the head of the Trade Committee in the European Parliament. In Germany, there is no lack of politicians who would be happy enough if this tiresome subject would simply flame out.

But that won’t happen. Thilo Bode has now gotten to work on the CETA Agreement with Canada, which is close to being signed. He determined that the precautionary principle is hardly mentioned in the agreement draft. “The EU has sold us out a long time ago,” says Bode.

Now he wants to fight against it. He doesn’t want to say how. It should be a surprise.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.