A Brief History of the Toilet

TRIVIA, 6 Jun 2016

Maria Popova, Brain Pickings – TRANSCEND Media Service

How the most appropriately named inventor in history saved humanity from a centuries-long crisis.

How the most appropriately named inventor in history saved humanity from a centuries-long crisis.

“Civilized man has always been outraged by what he sees, or else there would be no civilization,” Norman Mailer once wrote. And, in fact, among the greatest feats of civilization is a technology that has enabled us to get one of humanity’s most primal yet most outrageous sights as far away from us, and as quickly, as possible: the modern toilet.

From Bill Bryson’s wonderfully edifying At Home: A Short History of Private Life (public library) comes the curious history of how this staple of civilization came to be — a story not for the faint of heart or gut, but one brilliantly emblematic of how scientific innovation unfolds, with all its desperation-driven revolutions, cumulative advances, and dormant breakthroughs.

Bryson begins by tracing the colorful etymological history of the word itself:

Perhaps no word in English has undergone more transformations in its lifetime than toilet. Originally, in about 1540, it was a kind of cloth, a diminutive form of ‘toile’, a word still used to describe a type of linen. Then it became a cloth for use on dressing tables. Then it became the items on the dressing table (whence toiletries). Then it became the dressing table itself, then the act of dressing, then the act of receiving visitors while dressing, then the dressing room itself, then any kind of private room near a bedroom, then a room used lavatorially, and finally the lavatory itself. Which explains why toilet water in English can describe something you would gladly daub on your face or, simultaneously and more basically, water in a toilet.

Meanwhile, the fate of the actual toilet water — at what is referred to by that term today — was far less polished. As recently as the beginning of the 18th century, most sewage still went into cesspools, which were frequently neglected to a point of spilling into adjoining water supplies or overflowing into the streets. Bryson cites one man’s diary record of such an incident spurred by his neighbor’s neglected cesspit:

Meanwhile, the fate of the actual toilet water — at what is referred to by that term today — was far less polished. As recently as the beginning of the 18th century, most sewage still went into cesspools, which were frequently neglected to a point of spilling into adjoining water supplies or overflowing into the streets. Bryson cites one man’s diary record of such an incident spurred by his neighbor’s neglected cesspit:

Going down into my cellar… I put my foot into a great heap of turds … by which I found that Mr. Turner’s house of office is full and comes into my cellar, which doth trouble me.

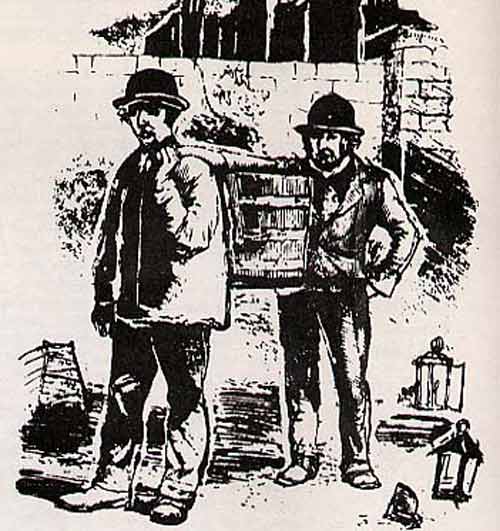

And just when one feels things couldn’t get any more nauseating, Bryson introduces the people who cleaned the cesspits, semi-euphemistically known as “nightsoil men.” Their duties put in perspective any present-day complaints about the struggle to find fulfilling work:

They worked in teams of three or four. One man — the most junior, we may assume — was lowered into the pit itself to scoop waste into buckets. A second stood by the pit to raise and lower the buckets, and the third and fourth carried the buckets to a waiting cart. Nightsoil work was dangerous as well as disagreeable. Workers ran the risk of asphyxiation and even of explosions, since they worked by the light of a lantern in powerfully gaseous environments.

Given this was unfolding during the heyday of Adam Smith, it is perhaps unsurprising that nightsoil workers made up for the extreme disagreeableness of the job and the skewed supply-demand ratio by charging formidable fees. This presented another problem: Poorer districts, often in the overcrowded inner city, couldn’t afford their services, which caused their cesspits to overflow regularly. Given the extreme population density — in London’s most compressed districts, 54,000 people were packed into a few blocks and one one report claimed that 11,000 lived in 27 houses on a single alley — this was a problem.

A new word crept into the vernacular to describe such neighborhoods: slums. Though its exact origin remains unknown, Charles Dickens was among the first to use it, in a letter penned in 1851.

A solution to the cesspit crisis was desperately needed. But when a successful one finally arrived, it wasn’t the result of a eureka! moment for groundbreaking technology — it was a concept that had been around since the end of the 16th century but, as is the case with many scientific and technological breakthroughs ahead of their time, had stopped short of perfecting the prototype enough to gain commercial traction.

That solution was the flush toilet, which John Harington, the godson of Queen Elizabeth I, had built for the Queen in 1597. Delight by his invention, she promptly installed it in Richmond Palace, but it never expanded beyond the royal dwellings. Bryson writes:

Almost 200 years passed before Joseph Bramah, a cabinet maker and locksmith, patented the first modern flush toilet in 1778. It caught on in a modest way. Many others followed… But early toilets often didn’t work well. Sometimes they backfired, filling the room with even more of what the horrified owner had very much hoped to be rid of. Until the development of the U-bend and water trap — which create that little reservoir of water that returns to the bottom of the bowl after each flush — every toilet bowl acted as a conduit to the smells of cesspit and sewer. The backwaft of odors, particularly in hot weather, could be unbearable.

The final link in this chain of problem-solving came from an inventor with perhaps the most brilliantly appropriate name in history: Thomas Crapper. Bryson ties the loose ends of the story:

[Crapper] was born into a poor family in Yorkshire and reputedly walked to London at the age of 11. There he became an apprentice plumber in Chelsea. Crapper invented the classic and still familiar toilet with an elevated cistern activated by the pull of a chain. Called the Marlboro Silent Water Waste Preventer, it was clean, leak-proof, odor-free and wonderfully reliable, and their manufacture made Crapper very rich and so famous that it is often assumed that he gave his name to the slang term crap and its many derivatives. In fact, crap in the lavatorial sense is very ancient, and crapper for a toilet is an Americanism not recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary before 1922. Crapper’s name, it seems, was just a happy accident.

In the rest of At Home: A Short History of Private Life, Bryson goes on to explore with equal parts wit and scientific rigor the everyday miracles in each room of the house and the colorful backstories behind those modern comforts we’ve come to take for granted, from pipes to pillows.

______________________________

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors.

Go to Original – brainpickings.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Within living memory are still the people collecting the toilet waste. My grandmother in Australia told me they called them the “Wednesday men” because they came that day once a week to remove the waste. I also remember in country areas a “Hygeia” toilet with a revolving base which allowed the swirling away of waste plus some water and a pleasing noise to let the user appreciate the process!!