DuPont May Dodge Toxic Lawsuits by Pulling a Disappearing Act

CAPITALISM, 20 Jun 2016

15 Jun 2016 – Sometime back in the early 1980s — Craig Skaggs can’t recall the exact year — a DuPont executive vice president ordered a thorough review of the company’s waste sites. A new hire named Martha Rees was given the job of compiling a list of all the places the company had manufactured, used, and dumped chemicals. “She was this young attorney that had been assigned this grunt work, really,” said Skaggs, who worked in government affairs for DuPont from 1974 until 2001. “And she’d come to my office frequently.”

It was a different era back when Rees started writing what would become known as “the Rees Report.” Love Canal, the environmental disaster in Niagara Falls, New York, in which a school was built on top of a toxic dump, had awakened Americans to the idea that industrial chemicals might be dangerous. Judging from Rees’s assignment, DuPont, which jointly owned a company that played a bit role in the Love Canal disaster, seems to have taken notice, too.

But appreciation of the extent of the harm posed by DuPont’s chemical plants dawned slowly, according to Skaggs. Back when the project began — and quickly expanded from a memo to a report to a “whole filing system” — the dangers of environmental waste were still remote and abstract enough for at least some at the company to joke about. “We used to call it a barrel of di-double-do-bad,” Skaggs said of the waste, which he recalls as being subject to the out-of-sight, out-of-mind treatment. “It was, take it to the dump, just dump it behind the building.”

Tracking the contents of all these barrels, pits, dumps, leaks, landfills, spills, and waste streams over time was a monumental task. Even back in the 1980s, the company, which was founded in 1802, had an environmental trail that defied cataloguing. “There were waste sites from the ’50s and ’40s,” said Skaggs, who remembers there being 113 plants at the time — and the waste sites as being far more numerous. “Waste would be hauled off in drums and taken to these sites and buried. And often, these sites were owned by other people.”

Rees was meticulous, combing through legal files within the company, interviewing employees who might know about older waste sites, and researching property records for evidence of the company’s disposal records over the years, according to Skaggs. “It was a huge thing,” he said, admiringly. “She did a great job.”

Martha Rees, who according to her LinkedIn profile retired from the company in 2015, did not return repeated calls inviting her to participate in this article. In response to inquiries about the Rees Report, DuPont spokesperson Daniel Turner wrote in an email, “It is hard to comment on the recollections of a former DuPont employee only to say that the employee may be mistaken.”

More than 30 years later, the question of how many waste and cleanup sites the company created in its more than two centuries of operation has taken on new urgency. Early this month, a trial got underway in Ohio over the industrial chemical PFOA (also known as C8). The trial is the fourth of six bellwether personal injury cases against DuPont stemming from a massive class-action lawsuit.

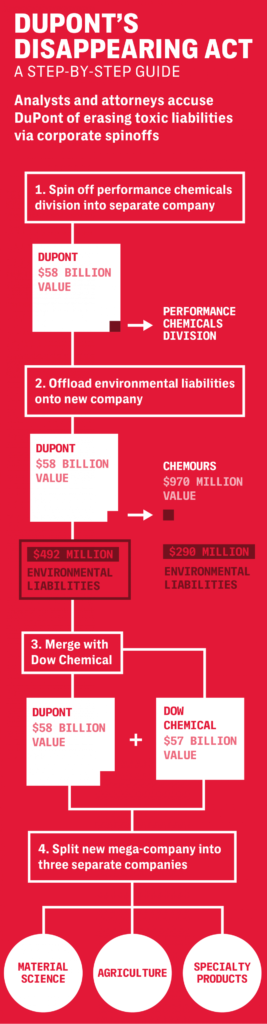

Last July, DuPont spun off its “performance chemicals” division, forming a new company known as Chemours, along with responsibility for a large portion of its environmental liabilities, including litigation over PFOA. Then, in December, DuPont announced plans to merge what was left of its company with another chemical giant, Dow, and to divide the resulting corporate colossus into three separate entities.

Together, the moves leave those struggling with DuPont’s environmental legacy with lots of questions. So even as they’re litigating the case of David Freeman, an Ohio man who developed testicular cancer after drinking water contaminated with PFOA, attorneys have also been asking the court to compel DuPont to demonstrate its ability to cover any awards to Freeman and other plaintiffs.

In particular, they want to know “where the liabilities and obligations of DuPont will fall” if the merger takes place. In their most recent legal brief in what is known as the Leach case, submitted on May 11 to Federal Judge Edmund Sargus, lawyers reiterated fears that the proposed Dow-DuPont merger “may be an attempt to extinguish DuPont’s liability” for claims related to PFOA. “DuPont reaped hundreds of millions of dollars in profits from the manufacture of C-8 at its Washington Works plant and is now taking the position that not one Leach class member is entitled to compensation for injuries linked to their exposure to C-8.”

In its own brief, filed on May 4, DuPont said there had been no decision yet as to how the emerging companies will handle the costs in the PFOA cases and called the plaintiffs’ request for documents premature as well as “improper and intrusive.” DuPont’s lawyers also said that the plaintiffs’ accusations that the company was dodging its responsibilities were “merely speculative.”

Those awaiting their day in court said they were worried not just that DuPont would try to duck out of its financial responsibilities, but that the company might disappear entirely. While DuPont has repeatedly promised that it will cover its liabilities, plaintiffs’ lawyers responded that those assurances are meaningless “if DuPont fails to exist, which is likely after the impending merger.”

“I’m afraid DuPont will vanish,” said Rob Bilott, the attorney who oversees the class-action suit.

A Financially Shaky Spinoff

The company DuPont spun off in July, Chemours — meant to rhyme with “Nemours,” as in DuPont’s founder, Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours — assumed a heavy load from its corporate parent. The assets it inherited — including 37 active chemical plants and DuPont’s fluorochemical division — accounted for just 19 percent of DuPont’s $35 billion in sales in 2014. Chemours also assumed 62 percent of DuPont’s environmental liabilities, including 174 polluted sites.

As part of the agreement, Chemours assumed legal responsibility for DuPont’s costs in “product liability, intellectual property, commercial, environmental and anti-trust lawsuits,” according to the filings. But some fear that Chemours will be unable to fulfill those obligations. Jeffrey Dugas, a spokesperson for Keep Your Promises DuPont, which represents people living near DuPont’s West Virginia plant who were exposed to PFOA, saw the spinoff as a deliberate dodge. “It looked to us like another way for DuPont to avoid paying the people of the mid-Ohio valley what they were owed,” said Dugas. “All of a sudden these massive liabilities are being transferred to a poorly capitalized company.”

Chemours’s first year has been financially shaky. Since opening at $21.00 a share a year ago, the company’s stock has fallen to $8.34. While DuPont has promised to cover some of the new company’s liabilities if necessary, that promise won’t necessarily cover all the company’s costs, as Chemours spelled out in its February SEC filings. “DuPont has agreed to indemnify us for such liabilities, but such indemnity from DuPont may not be sufficient to protect us against the full amount of such liabilities, and DuPont may not be able to fully satisfy its indemnification obligations.”

One financial website recently put Chemours’s chances of bankruptcy at 50 percent. Another, Citron Research, went further, concluding in early June that Chemours is “a bankruptcy waiting to happen,” and likening DuPont’s “dump-off” of liabilities to its treatment of PFOA itself. “While chemical giant DuPont has spent 60 years dumping waste around its facilities, they have spent the past 11 months dumping this ‘toxic spinoff’ on Wall Street.”

With Chemours’s creation, DuPont was “diabolically using the legal system to avoid liability,” according to Citron, which spelled out the gambit this way: “Create a bad entity that is designed to fail, so the good entity can be spared the reputational and liability damage.” The financial website predicted that it will take Chemours 18 months to go bankrupt, “just long enough for the new Dow/DuPont to split into three companies, and create separate entities that will all fight for indemnification from this financial toxic dumpsite of liabilities.”

Citron, which has been publishing for 15 years, concluded that the spinoff amounted to “complete securities fraud” and that Chemours is “the most morally and financially bankrupt company that we have ever witnessed.”

A February announcement that DuPont would also indemnify the individual members of Chemours’s board, ensuring that none of them faced personal financial consequences, was no doubt a relief to the executives, including CEO Mark Vergnano, whose current salary is about $1.33 million before stock options. But it rattled some close to the PFOA litigation. “It’s not right that individuals in a corporation can make decisions that endanger millions of people and then walk away,” said Paul Brooks, a West Virginia doctor who helped tally the health consequences of the chemical.

In an email, DuPont’s Daniel Turner wrote, “DuPont remains committed to continuing to fulfill all of its environmental and legal obligations in accordance with existing local, state and federal regulatory guidelines. The indemnification provision we agreed to with Chemours does not take away any valid legal claims that plaintiffs have against DuPont for pre-spin operations or the right to collect from DuPont if DuPont is found liable in any related action.”

The statement also said that “under state and federal law, most, if not all of the Chemours active environmental remediation responsibilities are guaranteed by surety bonds or other forms of insurance that name the government as the beneficiary. Should Chemours fail to perform, the government may step in and use these funds to complete any required remediation.”

Chemours declined a request to comment for this story.

A Coming Together of Equals

If all goes according to plan, a unified DowDuPont could emerge as soon as October. Though the mega-company is anticipated to have a combined market capitalization of $130 billion, it may be hard for plaintiffs to access any of that money.

“Moving assets around can make it more difficult to recover,” said Lawrence A. Hamermesh, a professor of corporate law at Delaware Law School. The merged entity assumes the debts of the original companies that formed it, said Hamermesh. And depending how Dow DuPont chose to organize those debts, “it could get complicated.”

It could become more complicated still after DowDuPont splits into three separate companies — one for agricultural chemicals; another for “specialty products” such as Kevlar, Tyvek, and food additives; and a third that will specialize in chemicals used in cars, food packaging, and pharmaceuticals.

“With all these spinoffs and individual companies, it’s possible that the company that carries through all of this could end up having very few assets,” said Hamermesh.

It’s possible, too, that Chemours’s financial woes could derail the planned merger altogether, according to Donald Baker, an anti-trust attorney hired by Keep Your Promises DuPont. Since the merger has been envisioned as a coming together of equals, in which the shareholders of each company would take a 50 percent stake in the combined company, a financial failure at Chemours could alter that equation. “If Chemours went under, then some of the assignments to Chemours might be set aside as fraudulent for purposes of bankruptcy law,” said Baker. If that happened, “the Dow shareholders might feel that giving DuPont 50 percent or close of the combined company wasn’t worth it because DuPont was responsible for this big turd.”

Significant Environmental Liabilities

The exact size of that turd is subject to both interpretation and change. Last July, DuPont counted 171 contaminated Chemours sites; Chemours has since upped the number of sites to 174. Citing “adverse” circumstances, Chemours also acknowledged that the bill for its environmental burdens might be $611 million higher than its first estimate of $290 million.

One reason for the upward revision could be the ballooning exposure of PFOA litigation. In October, DuPont was found liable for $1.6 million in the first of more than 3,500 personal injury claims relating to the chemical. In February, the company settled another PFOA case for an undisclosed amount. And starting in May 2017, 40 more claims over DuPont’s PFOA liability are slated for trial.

The EPA’s recently revised health advisory, which lowered the amount of PFOA acceptable in drinking water from .4 to .07 parts per billion, may also affect the calculations. According to Chemours’s latest SEC filings, three of the sites where it used or made PFOA are subject to the new lower levels. And “EPA has determined that additional public water systems and private residential wells around” two of those sites may have to be filtered.

Among the other legal burdens assumed by Chemours is the cost of litigation over benzene, a carcinogen contained in some of DuPont’s paints. In December, a Texas jury awarded $8.4 million to a painter who developed leukemia after using the paints for years. And at least 27 more benzene cases, expected to cost the company between $200 and $300 million, were pending as of December, according to Chemours’ SEC filings. The spinoff company also faces some 2,180 upcoming suits over asbestos; 83 pending cases over silica, which also causes a deadly lung disease when inhaled; and four over butadiene, a known carcinogen that DuPont used to make neoprene.

Chemours is also obligated to clean up Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, where DuPont manufactured explosives from 1902 until 1994, and where lead salts, mercury, volatile organic compounds, explosive powders, chlorinated solvents, and detonated blasting caps still contaminate groundwater and soil. Chemours’ SEC filings estimated that the remediation, which began in 1985, may cost as much as $116 million to finish. And some residents fear that number is too low. Lisa Riggiola, a former Pompton Lakes city council member, said that for years, she and others in the community have been asking for a full inventory of the chemicals DuPont used and dumped in their hometown so they can understand the full extent of the contamination.

“We’ve never we seen it,” said Riggiola. “We still don’t know everything we need to know about the site.”

No doubt a detailed report on DuPont’s historical production sites would be helpful in determining the true scope of DuPont’s and Chemours’s liabilities. But Dupont’s Turner says the “Rees Report” that Skaggs remembers is nowhere to be found. “To the best of our knowledge we have found no evidence for a ‘Rees Report’ regarding ‘waste sites,’” he wrote in an email.

For his part, Craig Skaggs is confident his recollection of the report Martha Rees began compiling 30 years ago is accurate. “I’m sure it still exists somewhere,” said Skaggs. “And I’m sure it’s retained by the legal department.”

____________________________________

Sharon Lerner – ✉sharon.lerner@theintercept.com

Go to Original – theintercept.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

A machine known as a decorticator was used for separating hemp fibres from the celluloid centre of the stems. In 1917, George Schlichten designed an improved decorticator, dramatically reducing labor costs associated with cleaning and preparing hemp for further processing. Schlichten spent 18 years on his design, before producing a decorticator that stripped the fibre from the plant much faster than on previous models. His objective was to stop the felling of forests for paper, which he believed to be a crime!

Lammot Dupont had bought the patents for nylon and other synthetic products. Fearing competition from hemp, that suddenly seemed competitive, he conspired with his banker Andrew Mellon, and with newspaper magnate Randolph Hearst, to re-name hemp ‘marijuana’ (stirring white fears of Mexican immigrants). He used the openly racist Harry Anslinger (formerly responsible for alcohol prohibition), to get cannabis banned. As we’re now learning, it was all based on lies.