The Good Society

PARADIGM CHANGES, 5 Sep 2016

Henning Meyer | The Next System Project – TRANSCEND Media Service

10 Aug 2016 – This paper is one of many proposals for a systemic alternative we have published or will be publishing here at the Next System Project. We have commissioned these papers in order to facilitate an informed and comprehensive discussion of “new systems,” and as part of this effort we have also created a comparative framework which provides a basis for evaluating system proposals according to a common set of criteria.

10 Aug 2016 – This paper is one of many proposals for a systemic alternative we have published or will be publishing here at the Next System Project. We have commissioned these papers in order to facilitate an informed and comprehensive discussion of “new systems,” and as part of this effort we have also created a comparative framework which provides a basis for evaluating system proposals according to a common set of criteria.

Introduction: A Brief Background

When the global financial crisis hit in 2007/08, many social democrats in Europe (and beyond) believed that their time had finally come. Deregulated financial markets had developed into a self-referential system that was becoming more and more detached from the wider economy. And when the finance industry collapsed, it had wide-ranging consequences, given global economic interdependency. The crash of Wall Street brought down not just other financial centers, like the City of London, but plunged the entire global economy into a deep crisis that is still not resolved to date.

It also became clear, quite quickly, that this global meltdown was bound to have significant political repercussions. Surely this should have been a “social democratic moment,” as the Oxford historian David Marquand mused. Wasn’t it social democracy that had always argued for appropriate regulation to steady inherently unstable markets? Wasn’t this just what had happened? Real world evidence emerged providing confirmation that one of the main planks of social democratic theory is right: markets need to be regulated to function properly.

Almost a decade on, it is fair to conclude that the “social democratic moment” never happened. In Europe, the political repercussions of the crisis have materialized as substantial political volatility and permanent emergency politics. The problems of the financial sector also corresponded with major shortcomings in the construction of the Euro. What started as a financial crisis quickly became a crisis of the entire Eurozone and the European Union at large; moreover, the refugee crisis added another dimension to the plethora of unresolved questions. The resulting political discontent has not benefited social democrats. So why is this the case and what does this mean for the future of social democratic politics?

In order to answer these questions, one has to understand the development of European social democracy in the decades before the economic crisis. In the 1990s and 2000s, Social Democratic parties assessed their situation and tried to determine why they had been significantly losing electoral appeal since the late 1970s. There were, of course, many country-specific explanations, but one common concern was that against the backdrop of the emerging free market doctrines, traditional social democratic politics looked outdated. The old ways were identified as to blame for declining electoral fortunes.

In reaction to this, and inspired by the experiences of the New Democrats and Bill Clinton in the US, many Social Democratic parties started a renewal process to adjust their political programs. This “Third Way” adjustment period basically led to different forms and degrees of social democratic accommodation towards the neoliberal mainstream. New Labour in Britain and the Neue Mitte in Germany were just two examples of different “Third Ways” that emerged all over Europe.

The term “Third Way” had of course been used for a long time with several different meanings before. In this 1990s context it was basically understood as a middle way between old style social democracy and neoliberalism. This middle way approach was often found in the presumed distinction between means and ends. Social democratic values were seen as permanent ends, but the means to achieve them were adaptable to new circumstances. “Good policy is what works” was an often-heard phrase. Of course, there is necessarily interaction between means and ends and it is far from obvious “what works.” Who decides the criteria of what works and doesn’t? As politics usually involve trade-offs, for whom does a policy work and for whom not? There have always been issues with these kinds of overly simplistic definitions.

This programmatic renewal of social democracy had several consequences. As it meant moving towards, rather than challenging, neoliberal political orthodoxy, the development of real political alternatives and visions was neglected. This was especially true of the acceptance of the “economization” of almost all areas of politics, including social policies, which led to a monolithic political discourse. Political renewal is always necessary and social democracy should, of course, learn lessons from conservative, green, and liberal ideas. But the extent to which this political adjustment process was conducted in many cases led to the accusation—one still heard to this day—that Social Democratic parties have sacrificed their core beliefs and have become almost indistinguishable from their political competitors.

In electoral terms, the Third Way worked well for a time. At the end of the 1990s, all but a few EU member states had governments led by social democrats. Many of them had implemented bold policy agendas based on their new politics. The Third Way seemed to have won the day.

Eventually, however, cracks started to appear. Fundamental problems emerged when the financial crisis revealed that all the old-fashioned social democratic talk about the inherent instability of markets was not that outdated after all, and that we were entering a period of global economic turmoil.

Cracks in the Foundation

At this point, what seemed like strengths before the economic collapse became fundamental weaknesses: as social democrats had neglected the development of an alternative political program in the previous decades, the crisis hit them while they were intellectually unprepared. There simply was no real political alternative on offer. Even worse, as many social democrats in government had pushed through deregulation agendas, they were not just seen as politically clueless, but as collaborators in a failing system. This led to a breakdown of trust and alienated significant parts of the traditional social democratic support—already disaffected by unpopular policy measures—even further. Against this backdrop, it is foreseeable that social democrats were not the political beneficiaries of the financialcrisis and new questions, such as how to deal with the Eurozone and refugee crises, have reinforced the lack of political orientation.

The reasons why the “social democratic moment” never happened are the backdrop to the contemporary challenges of social democracy. European social democrats struggle with the rapid change that is taking place around them. The Eurozone crisis requires bold decisions and further steps towards European integration that seemed unthinkable only a few years ago. The current refugee crisis requires coordinated European action too. The alternative to an integration leap forward is a process of renationalization, which has been equally unthinkable until recently but has—according to some commentators—already started.

The idea of a Good Society is based on “democracy, community, and pluralism.”

This political storm requires bold leadership and has hit social democrats ill prepared. The evolution from the global financial crisis to the Eurozone/refugee crises has further intensified the social democratic malaise. The Third Way period is over, but a genuinely new social democratic politics has not been established yet. The list of urgent tasks is daunting: social democrats have to redefine their political offering, rebuild credibility and trust, and, as if this was not enough, they must achieve this in the most turbulent political times in decades. The current struggles of social democracy are therefore unsurprising.

But not all is gloomy. Clarity about the task ahead will help to address it. A group of thinkers and practitioners from all over Europe has been working on a new social democratic politics for several years now. What has been developed under the concept of the Good Society is a new social democratic narrative that takes a thorough, value-driven analysis of our current economic and political problems as a starting point to craft a new politics. The underlying idea is to develop a political vision that provides direction. The goal is to define the Good Society in order to make a “better society” possible and sketch the political way towards it. Such a value-driven political compass provides an important tool to navigate the stormy political seas we are currently facing, and is a useful starting point from which to address wider challenges.

The idea of a Good Society is based on democracy, community, and pluralism. It is democratic because only the free participation of every citizen can guarantee true freedom and progress. The Good Society is based on a community approach because it recognizes our mutual interdependencies and joint interests. And it is pluralistic because it draws vitality out of the diversity of political institutions, economic activities, and cultural identities.

The Good Society is based on a community approach because it recognizes our mutual interdependencies and joint interests.

In practical terms, this means reestablishing the primacy of politics over economic interests. It means defending and expanding citizen rights, where possible, and transforming the relationship between individuals and the state into a new democratic partnership, one that strengthens transparency and accountability on all levels. The primacy of society means the supremacy of general social goods such as inclusion, education, and health over market interests. It also involves redistribution of wealth and power. The economic philosophy of the Good Society is rooted in the idea of an ecologically sustainable and just economic development that benefits the whole of society, not just a few at the top.

It is the lesson of the last decades that we have to rethink our current politics. One of Willy Brandt’s key observations is as potent today as it was several decades ago: “What is needed is a synthesis of practical thinking and idealistic striving.”[1] The ambition of the Good Society is exactly this: to be the synthesis of a realistic vision of a better society and the practical steps needed to get there. Will the way be easy? Of course not. But “it always seems impossible until its done,” as the late Nelson Mandela once said.

The Good Society approach also breaks with some of the political techniques that have run their course. During the Third Way period, policy making had a rather transactional character. Based on political research and focus groups, a political offer was developed that sought to cater to the identified needs of the electoral customer. The resulting politics was reactive rather than transformational. But in times in which the limits and constraints of our current economic and political systems have become all too obvious, a more ambitious politics is needed.

Political Transformation: A Challenge Accepted

The task for European social democracy is to analyze the current situation, read political trends, and develop a new politics based on this. The focus must be on the development of a new and convincing political agenda—one that is able to stand its ground, and win in the electoral competition—rather than reverse engineering a political agenda that has its starting point in a specific electoral target.

In the political arena, there is also an additional reason for why a new, values-driven approach such as the Good Society is needed for the revival of European social democracy. Societies are becoming more and more diverse and the logical consequence is that if you try to generate electoral success by targeting specific social segments with transactional politics, you are chasing groups that are continuously becoming smaller and more differentiated. Politics is thus becoming narrower and more exclusive in the process. A values-based political agenda should be able to create a broad buy-in, and unite otherwise diverse social groups drawn in by a positive social and economic vision.

Political change is, however, a slow process and takes place only in small steps alongside the necessities, and within the constraints, of day-to-day politics. Creating a new distinctive social democratic agenda is also difficult because the political competition is not static, and because, in an interdependent world, it is simply not good enough to build a Good Society in a European shell, let alone within national borders. The global dimension of the Good Society approach therefore deserves special attention.

Many of today’s most important issues, such as rising inequality, problems in the workplace and environmental degradation, simply cannot be addressed on a national or European scale. The Good Society project therefore aims to revitalize the internationalist tradition of social democracy and seeks to build alliances across the globe. The global nature of many political issues means that citizens are politically experienced, albeit differently, in countries across the globe.

The Good Society project aims to revitalize the internationalist tradition of social democracy and seeks to build alliances across the globe.

Reaching out and building bridges to other progressive traditions in various parts of the planet is therefore a vital part of the Good Society project. How are the same or similar political issues perceived in different parts of the world? What are other progressive solutions to these problems? And where are there connection points for discursive and political alliances that can help to conceptualize and address today’s pressing issues in a more aligned way? These are crucial questions that give the Good Society a truly global dimension; a dimension that social democracy has neglected in recent decades.

I have personally discussed the Good Society with thinkers and practitioners in Asia (South Korea, China, and Japan) and with representatives from different Latin American countries. There is openness and curiosity in Asia, especially as solid public welfare systems are largely missing. The experience with Latin America was more sobering. Even though there are discussions about “buen vivir” and “twenty-first century socialism,” the political content associated with these terms seemed very traditional and dogmatic. The obvious candidates for joint discussion in the future are the US and Canada, especially against the backdrop of current political developments in these countries.

A new regional political dimension is also a constitutive part of the Good Society. Be it in Europe, Asia, Latin America, or Africa, a new quality of regional integration of political ideas and discourses is a requirement for effectively addressing today’s pressing issues. The Good Society project is a hub for creating improved regional connections. It seeks to nurture and inspire the development and exchange of ideas.

And last, but not least, national Good Society activities should also be adapted to fit particular national circumstances. It is a great strength of the Good Society that it is not a one-size-fits-all approach that seeks to implement the same policies everywhere, regardless of specific circumstances and national traditions. The Good Society is, instead, an approach that is conceived as a political toolbox consisting of best practices and general policy guidance. These policies have common roots in the analysis of today’s pressing problems and the social democratic values underpinning this analysis. The continuous adaptation of the Good Society to different national circumstances, therefore, remains an important line of work.

Social democracy is in transition and it needs to adapt to the current political and economic circumstances. Small or simply rhetorical adjustments will not suffice and the digital revolution, which looks like the most transformative economic and social development in decades, is adding a completely new dimension, which is why we are now talking about the “Good Society 2.0.” Below, I will answer some more specific questions about the Good Society concept reinforcing some of the key points I have made in this brief introduction and adding more content and context.

Core Goals

Briefly, what are the principal, core goals your model or system seeks to realize?

The Good Society 2.0 aims to be a transformative political project that seeks to create policies designed to establish a more values-based society. The specific values in question are the social democratic core values of freedom, justice, and solidarity. It is a political project that seeks to establish economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable societies. The Good Society 2.0 seeks to shape the outcome of two meta trends that have been transforming our societies: the impact of our economic system and how the digital revolution is changing societies. We need a dynamic economy as a wealth creation engine, but our political economies have failed to make sure society as a whole benefits from this dynamism. The digital revolution threatens to bring with it similar distributional issues. There is a clear need for a new public policy approach to shape the social outcomes of these forces for change.

Major Changes

What are the principal changes you envision in the current system—the major differences between what you envision and what we have today?

First, the way policies are created needs to change. What we have seen too often across Western countries in recent decades is a transactional policy making approach that is primarily driven by electoral concerns, and which has led to a reversal of means and ends. Gaining office is a means to implement a policy agenda that has won support in a democratic election. But too often, winning the election is the end, and creating policies designed to win a specific election becomes the means. This has led to intellectual emptiness and a loss of trust in progressive parties. As this often goes along with assimilating conservative policies, this has also created a crisis of authenticity and identity. What is different about progressive political parties today?

Major modifications in the current system have to be preceded by adjustments to the way we formulate policies to govern and change the system.

The Good Society 2.0 is based on the need to reestablish a transformative policy approach that starts with an analysis of what is wrong and what kind of values-based policies could help to improve the situation, thus helping us move closer to a values- based Good Society. To be clear, the Good Society will never be achieved— there are not even the means to identify whether we live in a good society and societies are by definition dynamic and subject to constant change—but this kind of political narrative functions as a political compass. The goal is the journey.

Major modifications in the current system have to be preceded by adjustments to the way we formulate policies to govern and change the system. This should also include looking at a broader set of indicators above and beyond the often far too narrow focus on GDP. In recent years, a whole variety of new indicators to measure different elements of happiness and well-being have been developed. Also, choice design in public policy, often referred to as nudging, has seen some interesting developments. Public policy needs to be formulated on a broader foundation of concerns and relevant indicators.

Principal Means

What are the principal means (policies, institutions, behaviors, whatever) through which each of your core goals is pursued?

What is often referred to as “glocalism” has an equivalent in social democracy. Some years ago, I called this the necessity of unifying social democracy’s communitarian and cosmopolitan traditions. There is no necessary contradiction or trade-off in supporting and nourishing strong local communities, while at the same time being responsive and proactive about global problems.[2]

How can we bring about such change? So far, identifying the principal means to implement the Good Society approach—which means moving away from the short-term incentives of politics (at least to a degree)—has been the biggest problem.

Yet, the key to understanding the means through which change might be achieved is in the realization that, in recent years, progressive parties (in Europe, at least) have been managing their own decline whilst social, economic, and environmental problems have become more pressing, and have not been adequately addressed. There is a short-term incentive problem as most political decision makers are focused on day-to-day politics and the next election. For change to be

realized, there must be a break from this narrow focus.

We have already seen counterreactions such as Syriza, Podemos, and the election of Jeremy Corbyn as the leader of the UK Labour Party. These are likely to be reactions to past failures rather than the solution for the future, but they open up the political space to rethink what progressive politics is all about. This space should be used.

Geographic Scope

What is the geographic area covered by the model? If the nation-state, specify which ones or what category you address.

The Good Society project was conceived in the context of European social democracy and it is explicitly designed to fit the particular circumstances in different countries— which does not necessarily limit it to Europe. In addition, it involves an explicit international dimension. As many of the most pressing issues today are regional or even global in scope, there is an urgent need for more joined-up thinking (and practice).

Temporal Scope

Recognizing the large uncertainties, if there is a transition to the revised system about which you write, what would you suggest as a timeframe for the new system to take shape?

The key point about the Good Society approach is a change of direction rather than achieving any final state of affairs. A change of direction could be introduced reasonably quickly and is feasible, especially if introduced internationally at the same time. The most likely scenario for change, in my view, would be a reaction to a new crisis. We saw after the financial crisis in 2008 that internationally coordinated policy responses are indeed possible in crisis situations. This cooperative approach was, however, short-lived.

Where on the spectrum from imminently practicable to purely speculative would you place your proposals?

The proposal is imminently practicable.

Theory of Change

What factors or forces might drive deep change towards the system you envision? What is the explicit or implicit theory of change in your work? What is the importance of crises? Of social movements? Of available examples of change?

As mentioned above, a crisis of some form is often a catalyst for policy change. On top of this, however, social movements can play a crucial role in terms of agenda setting and bringing a topic into debate in political circles. The subject of inequality, also an important part of the Good Society approach, is one such example. Even though their organizational capacity might be weakened now, movements such as Occupy Wall Street and others have managed to get inequality firmly on the political agenda. President Obama even called it the defining issue of our time (as it also de facto makes the “American Dream” impossible). There has not been significant policy reaction, but working in the framework of broad progressive alliances to get a topic onto the political agenda is an important initial step. What’s the biggest problem or impediment for adoption of your model? Changing policy direction is very hard, especially if the political system is unresponsive because of personal incentives and power relations.

Some Specifics: Economy

Insofar as your work addresses the nature of the economy, how (if at all) do the following fit into the future you envision?

How are productive assets and businesses owned? Does ownership differ at different scales (community, nation, etc.)? Do forms of ownership vary by economic sector (banking, manufacturing, health care, etc.)?

The social democratic model of a Good Society is based on the notion of a mixed economy, in which different forms of ownership and organization exist alongside each other. The definition of public goods, including the securing of life risks such as ill health, is key in this context. It is perfectly fine to create a profit-seeking consumer electronics firm that seeks to maximize profit and get ahead in a competitive landscape. It is not clear to me why the securitization of individual life risks of citizens, for instance, should underlie the same logic. Here it is not clear why a profit-seeking private health insurance company should be the main mechanism to provide health security—not least because the profit motive conflicts with the provision of services. Here a nonprofit collective solution aimed at dispersing risk and providing needed services is a much better and (if one looks at the US health care cost structure) more efficient system. So, in essence, one needs to define the guiding logic of different parts of the economy and create structures that are suitable for this logic.

It is not clear why a profit-seeking private health insurance company should be the main mechanism to provide health security—not least because the profit motive conflicts with the provision of services.

The idea of a mixed economy is also the key distinguishing factor between social democracy and what is often referred to as socialism or democratic socialism. All these terms are linguistic minefields and many of the terms have been used interchangeably, in different countries and at different times. But as a rule of thumb, democratic socialists put a much greater emphasis on general public ownership of the means of production; whereas, social democrats advocate a mixed economy approach such as the one set out above.

How are public and private investment decisions made?

Investment decisions are made in the usual way, although governments urgently need to rediscover their role in proactive fiscal policies. The misguided dogma of austerity has led governments to significantly underuse fiscal policy and underinvest in many countries, particularly in Europe.

What is the role of private profit and the profit motive? Who owns and controls economic surplus?

See above. It depends on what the guiding principle in a segment of the economy should be. Profit seeking is fine in some sectors but not in others.

What is the role of the market for goods and services? For employment? Other?

In terms of wage setting, a conducive regulatory environment is crucial. From the Good Society perspective this includes national and international minimum wages (a European minimum wage was an early policy under the Good Society banner), as well as strong worker representation on the company and wider economic level, to make sure productivity gains are fairly shared. There is no general need to dismantle market functions, but it is crucially important to design a political economy that produces the desired outcomes in the primary, as well as the secondary, distribution of income.

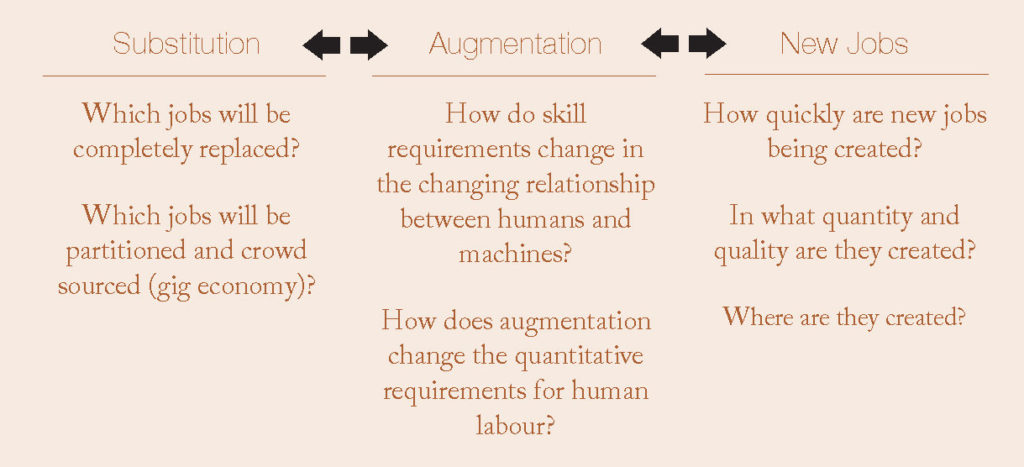

The digital revolution is likely to challenge our historic ideas about jobs and employment. There are three trends that need to be understood and which will play out in varying ways in different countries:

What role do you see for innovative corporate forms, coops, public enterprise, social enterprise, and public-private hybrids?

In the digital age, we will see many more forms of cooperation and economic activity. Depending on decisions about the distribution of the likely productivity gains coming with the digital revolution, we can also expect somewhat more leisure time in the future.

What is the evolution of the workweek (hours worked, say, per year)?

If productivity gains are used to reduce working hours, we will see much more flexible arrangements. This might impact hours worked per week, but is also likely to have an impact on total hours worked across the work life, where changes in hours occur, for instance, from early to mid to late career.

What role do you see for innovative corporate forms, coops, public enterprise, social enterprise, and public-private hybrids?

In the digital age, we will see many more forms of cooperation and economic activity. Depending on decisions about the distribution of the likely productivity gains coming with the digital revolution, we can also expect somewhat more leisure time in the future.

What is the evolution of the workweek (hours worked, say, per year)?

If productivity gains are used to reduce working hours, we will see much more flexible arrangements. This might impact hours worked per week, but is also likely to have an impact on total hours worked across the work life, where changes in hours occur, for instance, from early to mid to late career.

Progressives too often just dismiss finance rather than trying to capitalize on the possibilities to use it for progressive purposes.

What is the envisioned future of organized labor?

Trade unions are key to make sure that worker concerns are heard in the time of disruption we are likely to enter. They suffer from their own organizational problems, but will be indispensable if the digital society is shaped in a fair manner.

What are the roles of economic growth and GDP as a measure of growth in your system? What is the priority of growth at the national and company levels?

GDP is an important measure of economic activity but—as is well known— incomplete and sometimes even misleading. The Good Society approach also puts an emphasis on hard to measure or intangible measures of social well-being.

How is money created and allocated?

Monetary policy remains as it is. However, the functioning of financial markets and institutions needs to be reformed to avoid the kind of speculation and capital misallocation we have witnessed in the past. There is nothing inherently good or bad about finance.[3] It is a tool that should be used also for social purposes. Progressives too often just dismiss finance rather than trying to capitalize on the possibilities to use it for progressive purposes. Therefore, there will be activities in Europe this year under the banner of “progressive finance” to recapture this tool.

Some Specifics: Society

How do you envision the future course of income and wealth inequality? What factors affect these results?

We already have very high levels of inequality and two drivers are likely to worsen the situation further: the structural inequality problem of capital and the potential polarization of labor markets as a result of the digital revolution.[4] Shaping the digital revolution and rethinking taxation as well as capital ownership (employee ownership and public ownership) are therefore crucial. I have already referred to the need for a conducive political economy to moderate inequality in the primary and secondary distribution of income. This can, to an extent, be done via taxes and institutions (e.g. collective bargaining). But, if Thomas Piketty’s analysis in Capital in the Twenty-First Century holds, and there is a structural distributional imbalance in the relationship between growth and capital returns, then capital ownership needs to be rethought. This would provide the opportunity to resocialize capital returns. This could include (part) worker ownership of companies but also using financial vehicles—such as a sovereign wealth fund—to resocialize capital returns across the wider economy.

What, specifically, is the role of community in your model? What measures and factors affect community health, wealth (‘social capital’), and solidarity, and how central are local life, neighborhoods, towns and cities?

The Good Society seeks to combine an activist cosmopolitan outlook on global issues with a refoundation of social democracy’s communitarian roots. Too often there has been the assumption—sometimes explicit—that there is a conflict between these two dimensions. There is no necessary conflict between being responsive to global issues and at the same time creating strong local communities.The marrying of these two key dimensions is important.

Do you envision a change of values, culture and consciousness as important to the evolution of a new system? If so, how do these changes occur?

The Good Society is values-based, and the challenge is more to bring these values back into our daily political and social lives, rather than changing them.

How do “leisure” activities—including volunteering, care-giving, continuing learning—figure in your work?

I think we are moving into a much more colorful economic life in which the traditional economic categories of wage labor (reduced hours) and leisure sit alongside elements of the sharing economy (financial interest) and a new form of digital commons (not for profit). If the digital revolution is shaped well, we could have much richer and adaptive social and economic lives.

Some Specifics: Environment

In your work:

Do you envision the economy as nested in and dependent on the world of nature and its systems of life?

The Good Society is based on the notion of sustainability understood as social, economic, and environmental sustainability.

Do you envision addressing environmental issues outside the current framework of environmental approaches and policies (e.g. by challenging consumerism, GDP growth, etc.)?

GDP is an incomplete measure (as described above) but I see no reason why economic growth, per se, has to be environmentally degrading. If we solve the clean energy puzzle, which depends on political will and investment, many products and services we will buy in the future could be carbon neutral. I see no natural barrier here.

How do you handle environment-economy interactions, trade-offs, and interdependencies?

Environmental sustainability should be a guiding principle for all economic activities.

Some Specifics: Polity

To what degree would your proposed model require Constitutional change? What specifically might be required or recommended?

This highly depends on the countries in question. In the UK, for instance, constitutional reforms to strengthen localism would be very useful. This is not an issue in Germany where more robust structures already exist.

How does your model address questions of political and institutional power?

The seizure of the political system by special interests prevents the change that is needed. This is therefore a natural starting point. Milton Friedman, among others, believed that only a crisis produced real change. Another old expression is that “good government is just the same old government in a helluva fright.”

Do you examine crisis-driven political change and crisis preparedness?

Yes, as mentioned above, a crisis is the most likely trigger for change.

Do you envision social movements as important in driving political change and action? If so, can you elaborate on how this happens?

Social movements can be important to set the political agenda as mentioned above.

Real-World Examples, Experiments and Models

Are there other models that you see yourself aligned with or close to yours?

There are no other models that are directly connected, but creating points of contact with other progressive ideas is a crucial part of the Good Society. Even if the solutions might look a bit different, many of the problems are similar and a sense a mutual understanding and exchange is therefore important. The Good Society approach combines different social democratic welfare traditions (the Nordic system based on taxes and the German model based on social insurance, for instance). It provides a coherent analytical umbrella with a set of policy options that can be adapted to different circumstances in different places. I see it as a necessary development of European social democracy, and it would also help to avoid breaking up into different camps. If you look at the myriad of different responses to the current refugee crisis, for example, you could be forgiven for missing the allegedly joint value-basis of some Western and Eastern European parties.

NOTES:

[1]Willy Brandt and Leo Lania, My Road to Berlin: The Autobiograhy of the Crucial Mayor of Berlin and Biography of his Crucial City (London: Peter Davies, 1960), 286.

[2]Henning Meyer, “The challenge of European Social Democracy–Communitarianism and Cosmopolitanism United,” In Henning Meyer and Jonathan Rutherford, eds., The Future of European Social Democracy: Building the Good Society (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

[3]See Robert Shiller, Finance and The Good Society (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2012).

[4]On the structural inequality problem of capital, see Thomas Picketty, Capital in the Twenty-first Century, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2014).

_______________________________________

Henning Meyer is editor-in-chief of Social Europe and a research associate of the Public Policy Group at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is also director of the consultancy New Global Strategy Ltd. and frequently writes opinion editorials for international newspapers such as The Guardian, DIE ZEIT, The New York Times, and El País.

Go to Original – thenextsystemproject.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.