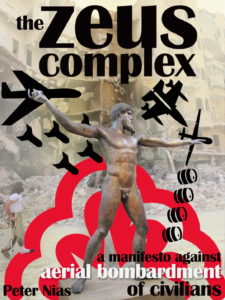

The Zeus Complex: A Manifesto against Aerial Bombardment of Civilians

MILITARISM, 7 Nov 2016

Peter Nias – TRANSCEND Media Service

31 Oct 2016 – Civilians have constantly suffered during wars, by direct violence or starvation or both. It has always been thus, in past centuries and now. Whether from the air or from the ground, they have been on the receiving end of abusing armies in city sieges, from impoverishing scorched earth, of Roman ballistas, the artillery of arrows and of cannon, and of bombs via airships, aeroplanes and missiles.

31 Oct 2016 – Civilians have constantly suffered during wars, by direct violence or starvation or both. It has always been thus, in past centuries and now. Whether from the air or from the ground, they have been on the receiving end of abusing armies in city sieges, from impoverishing scorched earth, of Roman ballistas, the artillery of arrows and of cannon, and of bombs via airships, aeroplanes and missiles.

Although the use in common parlance of the term ‘collateral damage’ is relatively new – since the mid 1980’s – its basis as applied to aerial bombardment of civilians in particular, dates back to Greek mythology and to religion. Zeus, the mythical king of the gods, used thunderbolts from the sky to spread fear and destruction. In a biblical way, God’s aerial bombardment of rain caused The Flood which wiped out humanity, save for Noah and family. Fire and brimstone destroyed the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah.

Have we have taken some of our justification of the 20th/21st century’s aerial bombardment from this background? While never overtly mentioned, such pedigree lurks subtly in these pedagogical heavens.

The aerial bombardment of children, women and men, whether deliberate or as ‘collateral damage’, continues to be one of many stains on the world’s ambiguous and uncertain paths towards civilisation. This article, based on a book published in November 2016, endeavours to give inspiration to readers, both popular and academic who, when hearing of civilian aerial bombardment and its grim consequences, sigh wearily and think ‘what can anyone do about it?’

Although there have been writings on both civilian collateral damage, and a lot more in the literature on human rights in such onslaughts, very few have tried to link the two. Even fewer have then tried to look for solutions. It’s about time this was seriously attempted.

Although there have been writings on both civilian collateral damage, and a lot more in the literature on human rights in such onslaughts, very few have tried to link the two. Even fewer have then tried to look for solutions. It’s about time this was seriously attempted.

I offer a manifesto of initiatives which are geared specifically at increasing the rights of humans in order to reduce the amount of civilian bombing. Such ideas are for influence in the long term, as measured in decades. There are no short term panaceas here.

A factor making this topic even more challenging is that the meaning and interpretations of ‘collateral damage of civilians’, and of ‘rights of humans’, have subtly and inversely changed since the end of the Cold War. On the one hand civilians have become less important in consideration of military tactics, and on the other hand protective human rights of such civilians are under greater political attack. The gap between them has widened, not narrowed.

In contrast, there have been seeds of positive human rights sown over the centuries. Some have fallen on stony ground, some have lain dormant and a few have flourished. We seem to be better at getting agreement to mostly military-type Geneva Conventions rather than to those geared to civilian protection. Even those that attempt to protect civilians are frequently poorly implemented, with the military being judge and jury in deciding what is ‘proportional’ collateral damage. Perhaps the main positive 20th century exception is the prohibition of gas by the 1925 Geneva Protocol, even if it is not always adhered to.

More ‘rights of humans’ are needed to counteract these situations, and not just by creating formal laws and conventions either. Greater physical protection, more acknowledgements when civilians are ‘damaged’, less acceptance of ‘expendable’ civilians in the first place, and many more. It’s a multi-faceted challenge.

For example, what has been done to meaningfully remember, and perhaps even to say sorry, when civilians – children, women, men -are ‘collaterally damaged’? Such posthumous recognition is rare, not least since the world wars, anywhere in the world. Only relatively recently, with the 70th/75th World War Two blitz anniversaries in the UK for instance, have there been, almost as an afterthought, small shrines to civilians who died. In adroit contrast, militaries everywhere take centre stage in publicly honouring their losses through formal remembrances and memorials.

It is mentioned above that, particularly since around 1990, there has been greater, albeit subtle, acceptance of collateral damage. Indeed, so-called smart weapons have made it easier for the military to claim proportionality in air strikes where civilians are involved. Some countries appear to have an increasingly cavalier and ‘don’t really care’ approach to the use of such weapons, albeit whilst claiming otherwise. They may also be reluctant to conduct post-use investigation when civilians are hit. There is perceived acquiescence in this scenario by too many uninterested populations and politicians elsewhere: the warring parties know this and exploit it accordingly. Thus the aforementioned gap – more a gulf – between the bombing of civilians, and of adhering to their rights as humans, is increasing. This is despite the determined efforts by supportive groups to bring it to world attention and action.

So what can be done, in the long term at least? We cannot just do more hand-wringing, however impotent we may feel.

I offer a manifesto of some forty initiatives. Some are micro and some are macro in nature, some are usual and some are very unusual topics. Individually they are certainly limited; cumulatively they may make a difference. To implement them, however, we all need to play a part, in whatever ways we can. They will not stop wars, but may make some wars more difficult to start and perhaps be less devastating to civilians when they do occur. It is a multiple stepping stone approach, which may well result in a successful giant leap.

Manifesto topics include naming affected civilians as ‘children-women-men’, not shrouding them in the veiled terminology of ‘collateral damage’ or the generalisation of ‘casualties’. Even the use of the description as ‘humans’ does not give them full justice.

The formal ‘cenotaph type’ of memorialisation and naming of each and all affected civilians, everywhere, should be done.

Also, might having a woman in charge of ‘bomber command’ result in a partial rethink of how tactics which may affect civilians are implemented? Militaries could formally use the term ‘blue on white’ when causing civilian casualties, in addition to the current ‘blue-on-blue’ for their own side. Sending accompanying astronauts from a much wider range of countries to the International Space Station may be useful, so when they return and tour their countries they can say that the Earth is a wonderful place where we should talk to rather than bomb each other. Having much greater creative economics, politics and military when it comes to the supply of weapons will help. At a semantic level, to discredit and replace the metaphorical use of the word ‘bomb’ in everyday language, such as the doubly ironic entitling of the ‘smart bombs’ which remove cancer cells (call them smart cells instead?).

Dozens more.

NOTES:

Peter Nias (2016) : The Zeus Complex : a manifesto against the aerial bombardment of civilians : from www.aerialbombardmentofcivilians.co.uk

Frederik Rosén (2016): Collateral Damage: a candid history of a peculiar form of death: pub Hurst

_____________________________________

Peter Nias is an independent social and peace researcher. He was formerly an honorary visiting research fellow in Peace Studies at the University of Bradford, UK.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 7 Nov 2016.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Zeus Complex: A Manifesto against Aerial Bombardment of Civilians, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.