Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier: Soul Brothers

CURRENT AFFAIRS, 27 Feb 2017

Charles M. Blow – The New York Times

20 February 2017 is Sidney Poitier’s 90th birthday. His best friend of 70 years, Harry Belafonte, turns 90 on March 1.

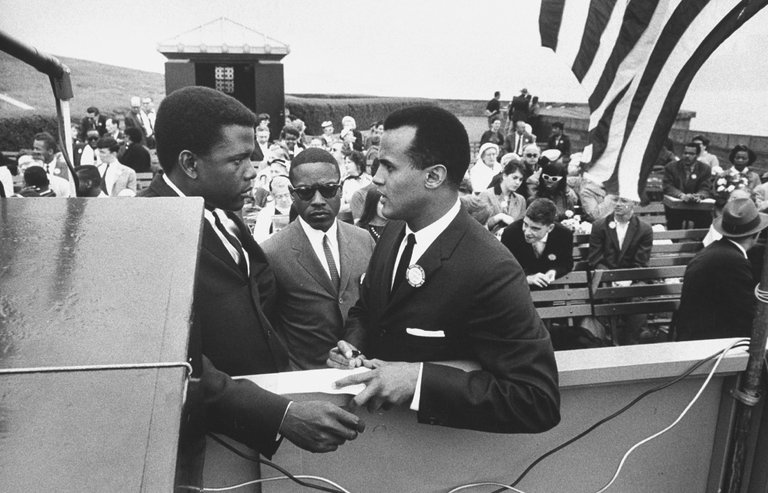

Sidney Poitier, left, and Harry Belafonte, right, at a civil rights rally with activist Bernard Lee, center. Credit Al Fenn/The LIFE Picture Collection, via Getty Images

20 Feb 2017 – Please allow me to divert my gaze for one day away from our national political darkness and toward two national rays of light.

This is an ode to and appreciation of the friendship — one of the most remarkable and resilient of our time — between two Hollywood royals.

Poitier and Belafonte didn’t meet until they were 20 years old, and yet Belafonte still considered Poitier his first real friend in life. As Belafonte put it, he lived a “nomadic” life as a child, shuttling back and forth between New York and islands of the Caribbean with his mother as she searched for work. “I did not get rooted long enough to develop what many people have the joy of experiencing, and that is childhood friends.”

The two men met at the American Negro Theatre, where Poitier worked as a janitor while studying with the company and where Belafonte worked as a stagehand. This was where they became performers.

The two men quickly broke through to each other, in part because they had so much in common. Not only were they the same age, they were both born to parents of West Indian heritage, enabling them to see the absurdity of racism in America from within and without and to bring a quasi-Pan-African sensibility to the African-American experience.

They shared the charmingly ordinary experiences that young friends share, like sneaking into the theater on the same ticket, each seeing half of a show, then filling each other in afterward on the half the other had missed. They called it “sharing the burden and the joy.”

And yet, by leaning on each other, supporting each other (Belafonte counseled Poitier though the dissolution of his marriage, which ended during his nine-year affair with actress Diahann Carroll), pushing each other, and yes, competing with each other (the first time Poitier was cast in a role, he was Belafonte’s understudy), they would both find tremendous popular success. Each man often took roles that the other had turned down or didn’t get.

In the 1950s Belafonte was dubbed the “King of Calypso” after his breakthrough album Calypso became the first LP in America to sell a million copies. In the early 1960s, Poitier became the first African-American to win the best actor Academy Award.

Even at the height of their success both men made an indelible mark on the Civil Rights Movement and changed the very idea of black masculinity.

In 1964, Belafonte convinced a hesitant Poitier to help him deliver $70,000 stuffed into a doctor’s bag to Freedom Summer volunteers in the South. They were met by Klansmen who chased them and fired guns at them. As one website put it, referring to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “The trip ‘solidified Poitier’s commitment to SNCC,’ and he would become the symbol of the group’s goals for African-Americans.”

For Belafonte’s part, he formed a committee to support the movement and raised thousands of dollars to help bail the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. out of jail, pay for the release of arrested protesters, help finance freedom rides and bankroll SNCC.

Belafonte and Poitier helped organize the March on Washington and helped plan King’s memorial after he was assassinated.

As for their impact on black masculinity, Belafonte has said of Poitier, “I don’t think anyone [else] in the world could have been anointed with the responsibility of creating a whole new image of black people, and especially black men.” In truth, Belafonte is being needlessly self-effacing here, because both he and Poitier accomplished this feat.

I’ve met both men and was enthralled by each. The first time I heard Belafonte speak in person, he spoke so eloquently and passionately that I was sure that he was reading a speech. He wasn’t. The next time I saw him I rehearsed a fan speech in my mind as I approached him, but before I could utter a word, he said to me, “I’m such a fan.” Mind. Blown.

When I was on my book tour, Poitier invited me to dinner in Beverly Hills. He was the most charming and graceful person I’ve ever met, famous or not. He told me: “I’m adopting you. I don’t have any sons. I have six daughters.” He insisted that I sign the book for him and his wife: “To Mom and Dad.”

Belafonte and Poitier demonstrated over a lifetime how celebrities could embody activism as well as the quiet power of dignity and grace.

King once said of Poitier: “He is a man of great depth, a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom. Here is a man who, in the words we so often hear now, is a soul brother.”

In fact, I think that is what Poitier and Belafonte found in each other: a soul brother. Happy birthday, gentlemen.

___________________________________

A version of this op-ed appears in print on February 20, 2017, on Page A19 of the New York edition with the headline: Harry and Sidney: Soul Brothers.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.