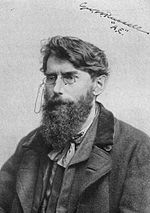

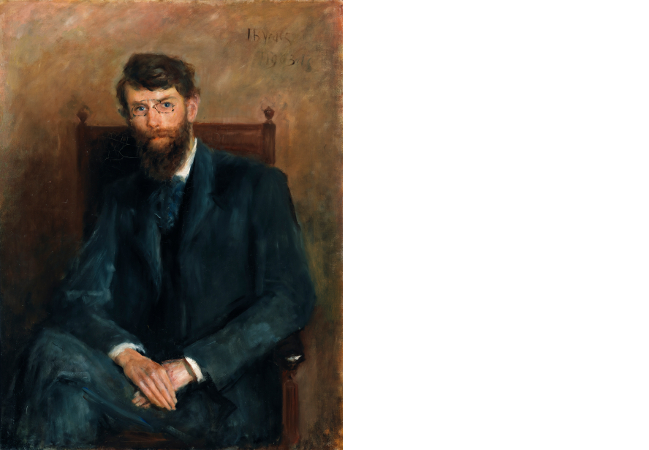

George William Russell (10 Apr 1867 – 17 Jul 1935): To See Things in the Germ, This I Call Intelligence

BIOGRAPHIES, 10 Apr 2017

Rene Wadlow – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Are there not such spirits among us ready to join in the noblest of all adventures— the building up of a civilization —so that the human might reflect the divine order? In the divine order there is both freedom and solidarity. It is the virtue of the soul to be free and its nature to love; and when it is free and acts by its own will, it is most united with all other life.”

— George William Russell, The Song of the Greater Life

George W. Russell was an Irish poet, painter, mystic, and reformer of agriculture in the years 1900 to the mid-1930s. He wrote under the initials A.E. and was so well known as A.E. that his friends called him “A.E.” and not “George”. He was a close friend and co-worker with William Butler Yeats who was a better poet and whose poems are more read today. Both A.E. and Yeats were part of the Irish or Celtic revival which worked for a cultural renewal as part of the effort to get political independence from England.

Ireland lived under a subtle form of colonialism rather than the more obvious Empire in Africa or India where domination was made more obvious by the distance from the center of power and the racial differences. The Irish were white, Christian, and partially anglicized culturally. English and Scots had moved to Ireland and by the end of the 19th century became the landed gentry. Thus Russell and Yeats felt that there had to be a renewal of Irish culture upon which a state could be built. Yet for A.E. political independence was only a first step to building a country of character and intellect “a civilization worthy of our hopes and our ages of struggle and sacrifice”. He lamented that “For all our passionate discussions over self-government we have had little speculation over our own character or the nature of the civilization we wished to create for ourselves…The nation was not conceived of as a democracy freely discussing its laws, but as a secret society with political chiefs meeting in the dark and issuing orders.”

For A.E. the truly modern are those engaged in meditation and spiritual disciplines, a way of reaching “the world of the spirit where all hearts and minds are one.” Unless the Celtic peoples create a new civilization, they will disappear and be replaced by a more vigorous race. An Irish identity must be open and unafraid of assimilating the best that other traditions have to offer. As A.E. wrote “To see, we must be exalted. When our lamp is lit, we find the house our being has many chambers…and windows which open into eternity.” As he said of Ireland, “a land where lived a perfectly impossible people with whom anything was possible.”

When the Irish Free State was created in 1919, the island was partitioned, Northern Ireland remaining part of the United Kingdom. Tensions between the Free State government and the Republicans who rejected the partition led to a civil war. Even after the civil war’s end in 1923, Republican resistance and general lawlessness continued throughout the 1920s. During its first decade the Free State government faced a serious crisis of legitimacy. It had to assert the new state’s political and cultural integrity in the face of partition and the lack of social change. In its economic structures, legal system, post-colonial Ireland looked much like colonial Ireland. Therefore the government stressed an “Irish culture” of the most repressive and narrow form. The Roman Catholic Church had a unique and virtually unquestioned monopoly on education in Ireland. Popular Irish nationalism had been structured around the antithesis between Ireland and England, and this continued after independence when it was said that all “immorality” — obscene literature, wild dances and immodest fashions — came from England. After 1923, the Catholic hierarchy fulminated most consistently and strongly against sexual immorality, not merely as wrong, but, increasingly from the 1920s on, as a threat to the Irish nation.

To counter this narrow, state organized vision of culture, A.E. put all his energies into a revival of rural Ireland through organizing the Farmers’ Co-operative Movement. He stressed that “the decay of civilization comes from the neglect of agriculture. There is a need to create, consciously, a rural civilization. You simply cannot aid the farmers in an economic way and neglect the cultural and educational part of country life…On the labours of the countryman depend the whole strength and health, nay, the very existence of society, yet, in almost every country politics, economics, and social reform are urban products, and the countryman gets only the crumbs which fall from the political table. Yet the European farmers, and we in Ireland along with them, are beginning again the eternal task of building up a civilization in nature — the task so often disturbed, the labour so often destroyed.”

Both A.E. and Yeats came from Protestant backgrounds and were deeply influenced by Indian thought reading the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads where sexual passion is the link between body, soul, and spirit. In his only novel The Avatars, A.E. wrote “such was the play of Helen which made men realise that beauty was a divinity. Such was the play of Radha and Krishna which taught lovers how to evoke god and goddess in each other.” The Avatar in Hindu thought is a spiritual being which takes human form in order to reveal the spiritual character of a race to itself such as Rama, Krishna or Jesus. In Indian thought the Avatar was always a man and came alone. But in A.E.’s story the Avatars are a man and a woman who teach the unity of all life as seen by the love between the two. There is but one life, divided endlessly, differing in degree but not in kind. “The majesty which held constellations and galaxies, sun, stars and moons inflexibly in their paths, could yet throw itself into infinite, minute and delicate forms of loveliness with no less joy, and he knew that the tiny grass might whisper its love to an omnipotence that was tender towards it. What he had felt was but an infinitesimal part of that glory. There was no end to it.”

A.E. knew that he was going against the current of the moment. As he wrote “There never yet

was a fire which did not cast dark shadows of itself.” At the end of the novel, the Avatars are put to death, but their teaching goes on “It is this sense of the universe as spiritual being which has become common between us, that a vast tenderness enfloods us, is about us and within us.” Yet below the surface of narrow tensions in Ireland A.E. saw that “We are all laying foundations in dark places, putting the rough-hewn stones together in our civilizations, hoping for the lofty edifice which will arise later and make all the work glorious.”

He lived the last years of his life in London, outside of Irish politics. He had a close friendship with Henry Wallace who became the first Secretary of the USA New Deal in 1933 and saw in the efforts to help the depression-hit farmers under Wallace his hope for rural renewal.

____________________________________________

René Wadlow, a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and of its Task Force on the Middle East, is president and U.N. representative (Geneva) of the Association of World Citizens and editor of Transnational Perspectives. He is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment.

René Wadlow, a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and of its Task Force on the Middle East, is president and U.N. representative (Geneva) of the Association of World Citizens and editor of Transnational Perspectives. He is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 10 Apr 2017.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: George William Russell (10 Apr 1867 – 17 Jul 1935): To See Things in the Germ, This I Call Intelligence, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.