Donald Trump Is Making Europe Liberal Again

EUROPE, 19 Jun 2017

Nate Silver | FiveThirtyEight – TRANSCEND Media Service

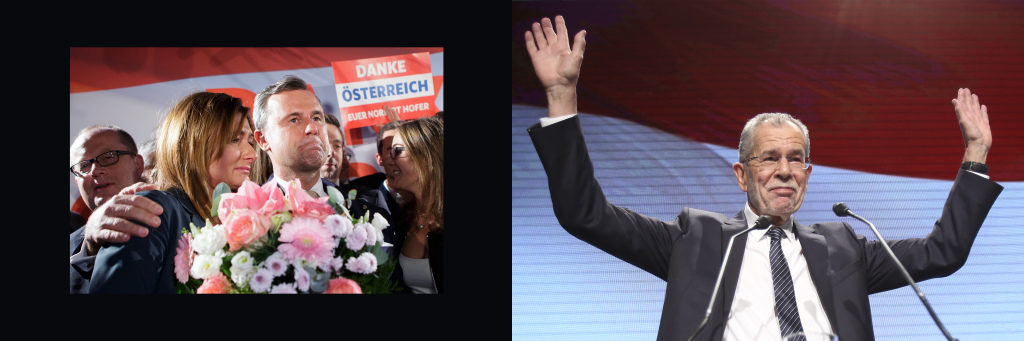

14 Jun 2017 – On Dec. 4 last year, less than a month after Donald Trump had defeated Hillary Clinton, Austria held a revote in its presidential election, which pitted Alexander Van der Bellen, a liberal who had the backing of the Green Party, against Norbert Hofer of the right-wing Freedom Party. In May 2016, Van der Bellen had defeated Hofer by just more than 30,000 votes — receiving 50.3 percent of the vote to Hofer’s 49.7 percent — but the results had been annulled and a new election had been declared. Hofer had to like his chances: Polls showed a close race, but with him ever so slightly ahead in the polling average. Hofer cited Trump as an inspiration and said that he, like Trump, could overcome headwinds from the political establishment.

So what happened? Van der Bellen won by nearly 8 percentage points. Not only did Hofer receive a smaller share of the vote than in May, but he also had fewer votes despite a higher turnout. Something had caused Austrians to change their minds and decide that Hofer’s brand of populism wasn’t such a good idea after all.

Left: Far-right candidate Norbert Hofer. Right: Independent presidential candidate Alexander van der Bellen.

Georg Hochmuth/AFP/Getty Images; Alex Domanski/Getty Images

The result didn’t get that much attention in the news outlets I follow, perhaps because it went against the emerging narrative that right-wing populism was on the upswing. But the May and December elections in Austria made for an interesting controlled experiment. The same two candidates were on the ballot, but in the intervening period Trump had won the American election and the United Kingdom had voted to leave the European Union. If the populist tide were rising, Hofer should have been able to overcome his tiny deficit with Van der Bellen and win. Instead, he backslid. It struck me as a potential sign that Trump’s election could represent the crest of the populist movement, rather than the beginning of a nationalist wave:

Wonder if Trump could hurt right-wing nationalist movements in Europe. People may associate movements with Trump. Trump way unpopular in EU.

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) December 4, 2016

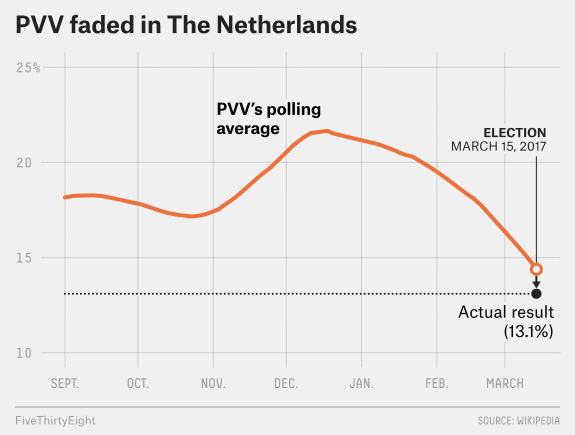

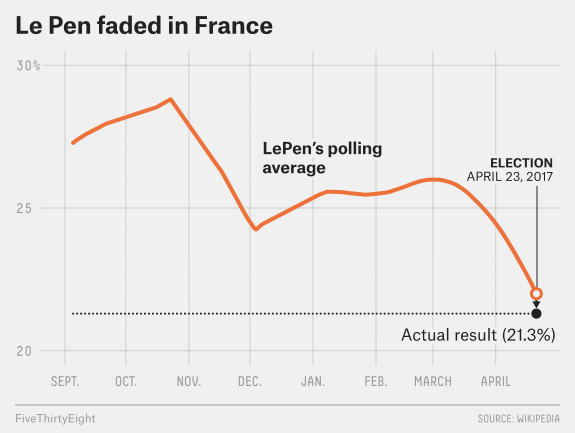

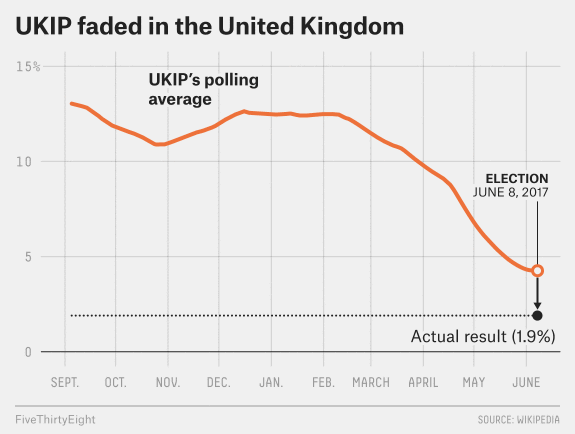

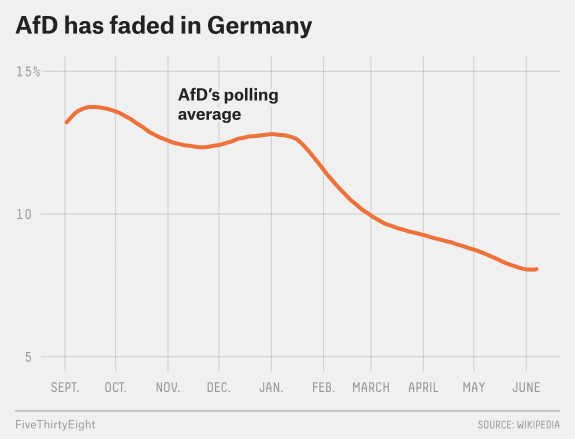

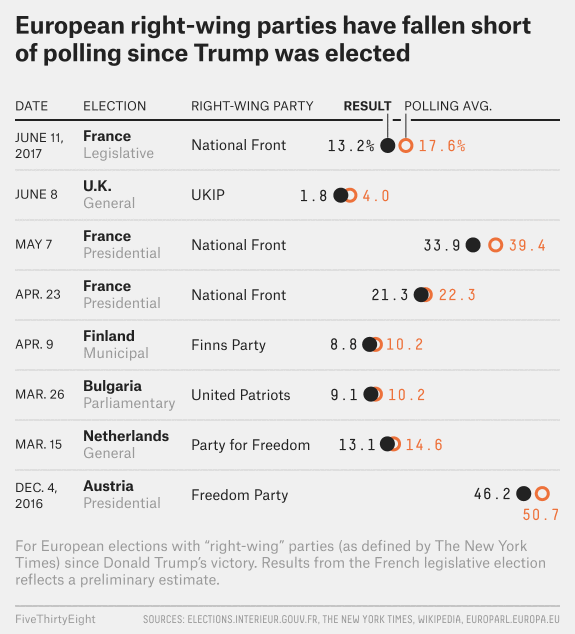

It was also just one data point, and so it had to be interpreted with caution. But the pattern has been repeated so far in every major European election since Trump’s victory. In the Netherlands, France and the U.K., right-wing parties faded down the stretch run of their campaigns and then further underperformed their polls on election day. (The latest example came on Sunday in the French legislative elections, when Marine Le Pen’s National Front received only 13 percent of the vote and one to five seats1 in the French National Assembly.) The right-wing Alternative for Germany has also faded in polls of the German federal election, which will be contested in September.

The beneficiaries of the right-wing decline have variously been politicians on the left (such as Austria’s Van der Bellen2), the center-left (such as France’s Emmanuel Macron) and the center-right (such as Germany’s Angela Merkel, whose Christian Democratic Union has rebounded in polls). But there’s been another pattern in who gains or loses support: The warmer a candidate’s relationship with Trump, the worse he or she has tended to do.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron have both been the beneficiaries of the right-wing decline.

Gabriel Rossi/LatinContent/Getty Images; Lionel Bonaventure/AFP/Getty Images

Merkel, for instance, has often been criticized by Trump and has often criticized him back. Her popularity has increased, and her advisers have half-jokingly credited the “Trump factor” for the sharp rebound in her approval ratings over the past year.

By contrast, U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May has a warmer relationship with Trump. She was the first foreign leader to visit Trump in January after his inauguration, when she congratulated him on his “stunning electoral victory.” But she was criticized for not pushing back on Trump as much as her European colleagues or her rivals from other parties after Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris climate accords on June 1 and then instigated a fight with the mayor of London after the terrorist attack in London two days later. Her Conservatives suffered a humiliating result, blowing a 17 percentage point polling lead and losing their majority in Parliament; it’s now not clear how much longer she’ll continue as prime minister. Trump was not May’s only problem, but he certainly didn’t help.

Let’s take a slightly more formal tour of the evidence from these countries:

The Netherlands

The Netherlands’ Geert Wilders, of the nationalist Party for Freedom (in Dutch, Partij voor de Vrijheid or PVV), hailed Trump’s victory and predicted that it would presage a populist uprising in Europe. And PVV initially rose in the polls after the U.S. election, climbing to a peak of about 22 percent of the vote in mid-December — potentially enough to make it the largest party in the Dutch parliament. But it faded over the course of the election, falling below 15 percent in late polls and then finishing with just 13 percent of the vote on election day on March 15.3 Those results were broadly in line with the 2010 and 2012 elections, when Wilders’ party had received between 10 and 15 percent of the vote. The center-right, pro-Europe VVD remains the largest party in the Netherlands.

France

Reciprocating praise that Le Pen had offered to Trump, Trump expressed support for Le Pen after a terrorist attack in Paris in April and predicted that it would “probably help” her to win the French presidential election. But over the course of a topsy-turvy race, Le Pen’s trajectory was downward. Last fall, she’d projected to finish with 25 to 30 percent of the vote in the first round of the election, which would probably have been enough for her to finish in pole position for the top-two runoff.4 Her numbers declined in December and January, however, and then again late in the campaign. She held onto the second position to make the runoff, but just barely, with 21 percent of the vote.5 Then she was defeated 66-34 percent by Macron in the runoff, a considerably wider landslide than polls predicted.

Le Pen’s National Front endured another disappointing performance over the weekend in the French legislative elections. Initially polling in the low 20s — close to Le Pen’s share of the vote in the first round of the presidential election — the party declined in polls and turned out to receive only 13 percent of the vote, about the same as their 14 percent in 2012. As a result, National Front will have only a few seats in the French Assembly while Macron’s En Marche! — which ran jointly with another centrist party — will have a supermajority.

The United Kingdom

While the big news in the U.K. was May’s failed gamble in calling a “snap” parliamentary election, it was also a poor election for the populist, anti-Europe UK Independence Party. Having received 13 percent of the vote in 2015, UKIP initially appeared poised to replicate that tally in 2017 (despite arguably having had its raison d’être removed by the Brexit vote). But it began to decline in polls in the spring, and the slump accelerated after the election was called in April. UKIP turned out to receive less than 2 percent of the vote and lost its only seat in Parliament.

UKIP’s collapse in some ways makes May’s performance even harder to excuse. Most of the UKIP vote went to the Conservatives, providing them with a boost in constituencies where UKIP had run well in 2015. But the Conservatives lost votes on net to Labour (although there was movement in both directions), Liberal Democrats and other parties. It’s perhaps noteworthy that Conservatives performed especially poorly in London after Trump criticized London Mayor (and Labour Party member) Sadiq Khan, losing wealthy constituencies such as Kensington that had voted Conservative for decades.

Germany

The German election to fill seats in the Bundestag isn’t until September, but there’s already been a fair amount of movement in the polls. Merkel’s CDU/CSU has rebounded to the mid- to high 30s from the low 30s last year. And the left-leaning Social Democratic Party surged after Martin Schulz, the former president of the European Parliament, announced in January that he’d be their candidate for the chancellorship (although the so-called “Schulz effect” has since faded slightly). Thus, the election is shaping up as contest between Schulz, who has sometimes been compared to Bernie Sanders and who is loudly and proudly pro-Europe, and Merkel, perhaps the world’s most famous advocate of European integration.

The losers have been various smaller parties, but especially the right-wing Alternative for Germany (in German, Alternative für Deutschland or AfD) and their leader, Frauke Petry, who have fallen from around 12 to 13 percent in the polls late last year to roughly 8 percent now. Meanwhile, both Schulz and Merkel have sought to wash their hands of Trump. Instead of criticizing Merkel for being too accommodating to Trump, Schulz instead recently denounced Trump for how he’d treated Merkel.

So if you’re keeping score at home, right-wing nationalist parties have had disappointing results in Austria, the Netherlands, France and the U.K., and they appear poised for one in Germany, although there’s a long way to go there. I haven’t cherry-picked these outcomes; these are the the major elections in Western Europe this year. If you want to get more obscure, the nationalist Finns Party underperformed its polls and lost a significant number of seats in the Finnish municipal elections in April, while the United Patriots, a coalition of nationalist parties, lost three seats in the Bulgarian parliamentary elections in March.

Despite the differences in electoral systems from country to country — and the quirky nature of some of the contests, such as in France — it’s been a remarkably consistent pattern. The nationalist party fades as the election heats up and it begins to receive more scrutiny. Then it further underperforms its polls on election day, sometimes by several percentage points.6

While there’s no smoking gun to attribute this shift to Trump, there’s a lot of circumstantial evidence. The timing lines up well: European right-wing parties had generally been gaining ground in elections until late last year; now we suddenly have several examples of their position receding. Trump is highly unpopular in Europe, especially in some of the countries to have held elections so far. Several of the candidates who fared poorly had praised Trump — and vice versa. He’s explicitly become a subject of debate among the candidates in Germany and the U.K. To the extent the populist wave was partly an anti-establishment wave, Trump — the president of the most powerful country on earth — has now become a symbol of the establishment, at least to Europeans.

There are also several caveats. While there have been fairly consistent patterns in elections in the wealthy nations of Western Europe, we have little evidence for what will happen in the former nations of the Eastern Bloc, such as Hungary, which has moved substantially to the right in recent years. (The next Hungarian parliamentary election is scheduled for early next year.) Turkey is a problematic case, obviously, especially given questions about whether elections are free or fair there under Tayyip Erdogan.

And even within these Western European countries, while support for nationalist parties has generally been lower than it was a year or two ago, it may still be higher than it was 10 or 20 years ago.

Politics is often cyclical, and endless series of reactions and counterreactions. Sometimes, what seems like the surest sign of an emerging trend can turn out to be its peak instead. It’s usually hard to tell when you’re in the midst of it. Trump probably hasn’t set the nationalist cause back by decades, and the rise of authoritarianism continues to represent an existential threat to liberal democracy. But Trump may have set his cause back by years, especially in Western Europe. At the very least, it’s become harder to make the case that the nationalist tide is still on the rise.

_______________________________________

Nate Silver is the founder and editor in chief of FiveThirtyEight.

Go to Original – fivethirtyeight.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.