Concept and Definition of Civil Society Sustainability

CIVIL SOCIETY, 10 Jul 2017

Charles Kojo VanDyck | Center for Strategic and International Studies – TRANSCEND Media Service

The Civil Society Ecosystem

30 Jun 2017 – The global civil society ecosystem can be characterized as a complex and interconnected network of individuals and groups drawn from rich histories of associational relationships and interactions. Globally, the concept of civil society has evolved from these associational platforms to comprise a wide range of organized and organic groups of different forms, sizes, and functions. There have been significant changes over time in the civil society landscape. At different periods, community-based organizations, workers’ or labor unions, professional associations, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have been the most prominent.

Consequently, defining civil society is not a simple task. Inasmuch as there is evidence of similar experiences across continents and regions, countries, and more specifically, groups that share similar cultural values and attributes within a country, have some distinct forms of social organization, cultural and political traditions, as well as contemporary economic structures.

Numerous academics and practitioners have proffered definitions for civil society based on their research and experiences. The most commonly used definition was created by CIVICUS, which conceives of civil society as the arena outside the family, the state, and the market, which is created by individual and collective actions, organizations, and institutions to advance shared interests (CIVICUS, 2011; PRIA et al., 2012). This definition has been widely accepted and utilized within various platforms. However, it is critical that the definition of civil society represents its current evolution, nuances, and growing diversity. A proposed definition that captures its current form is “an ecosystem of organized and organic social and cultural relations existing in the space between the state, business, and family, which builds on indigenous and external knowledge, values, traditions, and principles to foster collaboration and the achievement of specific goals by and among citizens and other stakeholders.”

Civil society within this context comprises qualities associated with goals, relationships, contextual experiences, values, and informal and formal structures. In recent times, the different typologies of civil society are:

- Civil society organizations (CSOs) comprising NGOs, faith-based organizations, and community-based organizations that have an organized structure and mission and are typically registered entities and groups;

- Online groups and activities, including social media communities that can be “organized” but do not necessarily have physical, legal, or financial structures;

- Social movements of collective action and/or identity, which can be online or physical;

- Labor unions and labor organizations representing workers; and

- Social entrepreneurs employing innovative and/or market-oriented approaches for social and environmental outcomes.

The State of Civil Society

Globally, civil society groups have been active in addressing social problems; however, the effectiveness of civil society in bringing about real change has been called into question due to varying factors, including increasing public distrust and uncertainty about their relevance and legitimacy. Also, a popular but disquieting trend has been the introduction of legislative and administrative policies by governments that stifle civil society operations. In addition, especially for civil society based in the global south, dwindling donor funding and shifting priorities driven by foreign policy considerations pose a threat to their sustainability.

Civil society organizations also face questions about their relevance, legitimacy, and accountability from governments and their primary beneficiaries due to a widening gap between the sector and government officials, on the one hand, and between their purported beneficiaries or constituents on the other. Many governments have increasingly become more emboldened and sophisticated in their efforts to limit the operating space for CSOs, especially democracy and human rights organizations.

A vivid example of the growing adversarial relationship between governments and human rights organizations is the widespread establishment of government-organized nongovernmental organizations (GONGOs) to infiltrate and gather information on the human rights community. This situation has made a significant number of human rights, humanitarian, training, and grassroots organizations dedicated to representing and ensuring the rights of citizens reluctant to engage and collaborate with governments.

Moreover, there has been a failure of “organized,” otherwise known as “traditional,” civil society organizations in maintaining connections with constituencies that they represent. A significant number of organizations have failed in upholding their mandates in the face of adversity. Some organizations have decided to “follow the money,” even though the funds are earmarked for programs and initiatives that do not align with their core mandate. The focus of these organizations becomes survival rather than fulfilling their missions. Also, global shifts in donor funding and withdrawals have adversely affected the ability of some organizations to continue to operate and exist. There is also a growing perception that CSOs have generally deviated from their initial mandate of promoting the rights of citizens, demanding for good governance, accountability and transparency from government.

Though the gap between the people and organized CSOs keeps widening, new actors in the sector—such as social movements, online activists, bloggers, and other social media users—are bridging the divide through their mode of engagement, tools, and approaches, which have democratized the advocacy space. In addition, the challenge is for the two main actors, traditional organized civil society and the trendy and loosely formed organic actors, to identify means of collaboration and focus on comparative advantages. Both actors need to analyze the rapid changes taking place within civil society and the development landscape and subsequently adapt their approaches, tools, and capacities.

Definition of Civil Society Sustainability

Within the context of the current global political and socioeconomic climate, what is civil society sustainability? This is what this section will attempt to define. According to Benton and Monroy (2004), sustainability is the ability of a given organization to improve its institutional capacity to continue its activities among target populations over an extended period of time, minimize financial vulnerability, develop diversified sources of institutional and financial support, and maximize impact by providing quality services and products. In recent publications that assess civil society’s sustainability commissioned and produced by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), CIVICUS, and the West Africa Civil Society Institute (WACSI) (CIVICUS, 2013: 2014; USAID;2015: 2016; WACSI, 2015), sustainability is characterized as an outcome of particular conditions.

For example, WACSI’s research revealed that civil society sustainability is a generic concept defined more by the context of its application than by any settled meaning. This means that there is no recognized universal definition of civil society sustainability but contextual definitions drawn from its applicability in a specific environment. It can better be understood by description rather than definition. It is largely a process, although it can equally be a goal in its own right and entails more than just availability of funds. It is also a broader and holistic concept, which goes beyond survival toward thriving, resilience, autonomy, independence, and continuous functioning.

WACSI’s research on sustainability identified four dimensions and fifteen different criteria and indicators. The four dimensions are: financial (the continuous availability of financial resources), operational (capacity, technical resources, and administrative structures to operate programs), identity (long-term existence of organizations themselves), and interventions (results and impact of specific projects after their completion or funding terminates).

In addition, the annual CSO sustainability index conducted by USAID is based on an assessment of legal environment, organizational capacity, financial viability, advocacy capacity, service provision, infrastructure, and public image and reputation. CIVICUS’s assessments also focus on structure, systems, operating space, identity, and impact.

However, these dimensions may not be a sufficient explanation and representation of the factors that influence the sustainability of the various groups within the civil society ecosystem. Often, the criteria used to measure the sustainability of civil society are heavily influenced by a donor’s funding policies and practices. These policies and practices are often designed to provide short-term grant support and very minimal long-term core funding. This drives the donor’s short-term orientation toward civil society sustainability, which emphasizes systems and structures without taking into consideration external factors such as democratic space and foreign policy. Therefore, it would be imperative to construct a definition that encompasses both the internal (controllable) dimensions and the external influences that impinge on the level of sustainability of the sector. Developing a more holistic definition will set the basis for more comprehensive and meaningful research on the future operations and resourcing of civil society.

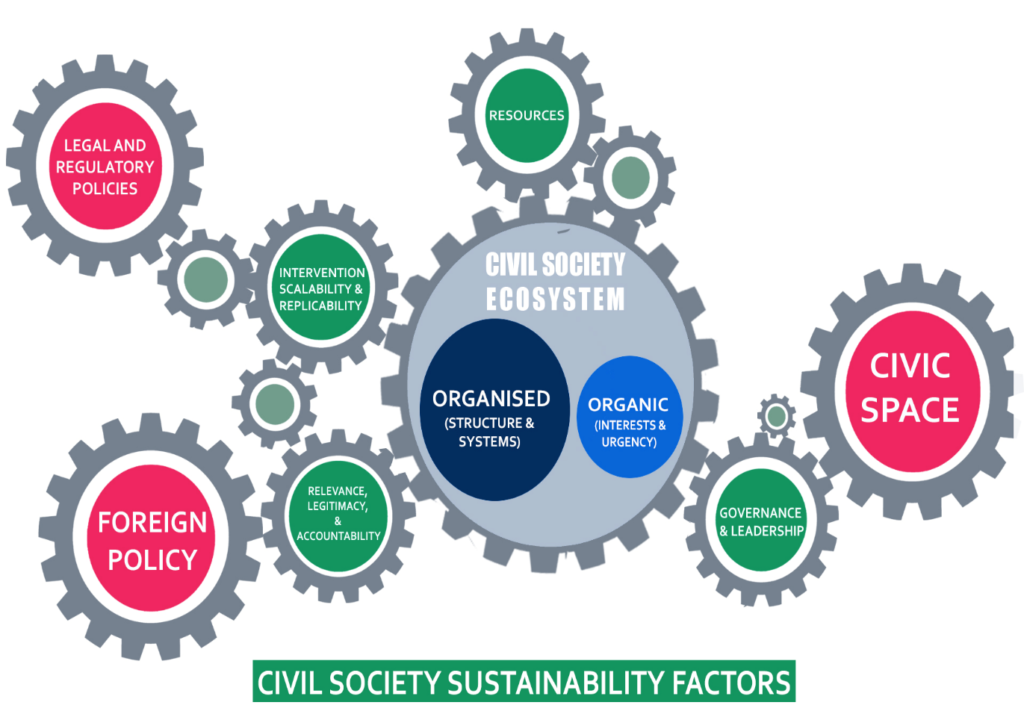

The above illustration is an attempt to visually convey a holistic representation of the various factors influencing the sustainability of civil society and their various interactions. The most immediate factors are governance and leadership (operations); resources (material, financial, and technical); relevance, legitimacy, and accountability (identity and representation); and intervention scalability and reliability (societal impact). The external factors are the nature of civic space (open, closing, or closed), legal and regulatory policies (enabling or restrictive), and foreign policy (national priorities and global geopolitical positions).

Drawing from these factors, the researcher is proposing the following working definition for civil society sustainability. Civil society sustainability may be defined as the capacity and capability of organized and loosely formed citizens associations and groupings to continuously respond to national and international public policy variations, governance deficits, and legal and regulatory policies through coherent and deliberate strategies of mobilizing and effectively utilizing diversified resources, strengthening operations and leadership, promoting transparency and accountability, and fostering the scalability and replicability of initiatives and interventions.

Conclusion

The relationship between donors and particularly civil society in the global south needs to shift in order to guarantee its sustainability. Currently, civil society’s relationships with donors are ad hoc, short term, and project based rather than formalized and long term. Civil society is often seen as implementers of donors’ development or foreign policy agendas. Donors operating in the global south do not feel the obligation to support civil society in becoming established, robust, or sustainable beyond project timelines.

Therefore, it is imperative for civil society, particularly in the global south, to shift focus and strengthen their abilities to mobilize resources from their own domestic constituencies and reduce the excessive dependency on foreign donors. This new narrative would be a complete departure from the approach civil society has pursued since the post–Cold War era.

________________________________________

Charles Kojo VanDyck is a member of the International Consortium on Closing Civic Space (iCon) at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C., and the head of the Capacity Development Unit at the West Africa Civil Society Institute (WACSI) in Accra, Ghana.

This report is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2017 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.