Latin America’s “Pink Tide” and the Challenge of Systemic Change: Bolivia

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN, PARADIGM CHANGES, 28 Aug 2017

The Next System Project – TRANSCEND Media Service

Introduction

7 Aug 2017 – In the late 1990s and the 2000s, Latin America experienced a “pink tide” of sorts, with a number of self-proclaimed socialist governments coming to power from Nicaragua to Venezuela to Uruguay and beyond. Several of these governments were able to implement radically progressive political agendas that increased social spending, nationalized important industries and renegotiated trade deals. A handful even presided over the writing of new constitutions, setting precedents by codifying the rights of nature and redefining their economies to make a more significant role for “solidarity economies” and the cooperative sector.

By 2010, leftist governments were in power in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela, with Peru joining the ranks in 2011. But not long after, the tide began to turn. In 2012, Paraguay’s leftist President Fernando Lugo was impeached, and though his party maintained control through the end of that presidential term in 2013, new elections saw the right-wing Partido Colorado come back to power, bringing modern Paraguay’s few short years of progressive rule to an abrupt end.

In 2015, businessman and former mayor of Buenos Aires Mauricio Macri was elected President of Argentina, becoming the first democratically elected right-wing President in nearly one hundred years. The following year, President Dilma Rouseff of Brazil’s Worker’s Party was impeached and succeeded by conservative Michel Temer. And though Hugo Chávez’s successor Nicolás Maduro remains in power in Venezuela, he and his United Socialist Party’s hold on power is ever more tenuous. Brazil and Argentina are two of the top three largest economies in Latin America and important political and economic partners of many other countries in the region, therefore, the return to conservative rule in both may have more widespread effects across the region.

Whether or not we consider these changes evidence of the end of an era, these recent shifts in the South American political landscape present an important opportunity to reflect upon the experiences of the pink tide countries. When we think about what it takes to create system change, what can we learn from their experiences? What institutional innovations have they modeled? Which political strategies seemed to be most successful and why? In order to begin to answer those questions, we chose to examine three of the pink tide countries in which leftist governments have been in power the longest: Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador. We asked three analysts to describe some of the institutional innovations implemented in these countries during this time, and to reflect on the relationship between organized citizenry and the state in these transitions in order to elicit lessons learned.

Major themes of the essays include: 1) factors that have helped or hindered the institutionalization of new policies and programs pursued by these governments 2) economic dependence and natural resource exploitation 3) the relationship between social movements and the state, especially with respect to how those relationships affect the possibilities for consolidation of progressive gains. As the United States confronts its own political crossroads, we hope the insights here can contribute to a sharpening our analysis of political change and help further our understanding of the possibilities—and challenges—that await us as we pursue system change.

******************************

Evo’s Bolivia: the Limits of Change

By Linda Farthing

Landlocked Bolivia, South America’s economically poorest and most indigenous country, is a land of extremes, that often provides a striking reflection of regional political and social trends. The last eleven years of Evo Morales’ government is no exception.

Centuries of exploiting its natural resources wealth for export — first silver, then tin, now natural gas — has left Bolivia heavily dependent on the fluctuations of international commodity markets. Despite its physical and cultural heterogeneity, Bolivia has always had a small, weak and highly centralized government and historically power has been concentrated in a small, light-skinned elite.

Indigenous and working-class Bolivians have always resisted this scenario, erupting in periodic rebellions since the Spanish invasion 500 years ago, and since the 1950s through the miner-led Central Obrera Boliviana (Bolivian Workers Central – COB) —in its heyday, one of the world’s strongest union movements. As the COB declined with neoliberalism’s onset in the 1980s, a slew of movements organized around indigenous rights, struggles for urban services and resistance to the US War on Drugs took up its mantle.

The Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) began as a “political instrument” of these movements (not a political party), particularly the coca growers’ union. Until 2002, MAS was rural-based and inclined to mostly horizontal decision-making. After 2002, it became increasingly urban with indirect grassroots ties giving way to direct and individual party affiliation.1

When the MAS was elected in late 2005, Bolivia’s social movements ranked among the world’s most radical, with defiant resistance traditions dating from the Spanish invasion, and particularly honed since they played a critical role in the 1952 middle-class led Revolution.2 Centuries of marginalizing most of the country’s population from the political process created a political culture where conflicts are frequently resolved by protests and blockades followed by negotiation. These movements tended to be male-dominated and controlled, as well as heavily shaped by patronage relationships.3 This was true during most recent protest cycle (2000 to 2005), when neighborhood organizations, and peasant, indigenous, workplace, and informal sector unions rebelled against neoliberalism.

Together, these movements launched coca grower Evo Morales to power in 2006 explicitly to expand economic and social justice. The Morales government quickly semi-nationalized natural gas production, expanded services and infrastructure (particularly for the poor), and prioritized long-abandoned rural areas. Framed around concepts of decolonization and living well (Vivir bien), in 2009, a government-supported Constituent Assembly adopted one of the world’s most progressive constitutions. Among its provisions are legislative parity for women and an extension of indigenous rights, including autonomy.

The new government appointed an unprecedented number of women, indigenous and working-class people to high government posts, including as Ministers. Three new Ministries have been created, including a Ministry of Transparency and Fight against Corruption (Ministerio de Transparencia y Lucha contra la Corrupción).

Eleven years later, the middle class has grown by a million people (10% of the population) and both the government and the economy have tripled in size.4 Largely thanks to the same type of conditional cash transfers adopted throughout Latin America, government investment and tripling the minimum wage, poverty has dropped by half, and income inequality as measured by the Gini index declined from 58.7 in 2006 to 48.4 by 2014.5 In 2017, Bolivia has the region’s highest growth rate, and the highest financial reserves per capita, which allow it to avoid the International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreements in force for the previous 20 years.6 By any measure, and certainly compared to its predecessors, what the MAS government has achieved is remarkable.

Nonetheless, the country’s underlying economic structure remains largely untouched. While a new class of often indigenous truckers, merchants, contraband traders and small mine owners have become wealthy, and the traditional elites have largely lost direct political power, their economic status is largely unchanged. Elites in the eastern economic powerhouse of Santa Cruz have grown even more powerful, though after spearheading a failed right-wing attempt to overthrow Morales’ administration in 2008, most now ally themselves with government.

The MAS government has paid little attention to reforming politics and governance.7 Eleven years on, both remain fundamentally unaltered. When MAS expanded into urban areas, political operatives of all stripes climbed onboard, gradually transforming it into a more traditional party with clientelism and patronage at its core. Over time, the numbers of women and indigenous people in high government posts declined as an ever-smaller entourage around the President and Vice-President amassed power.8

When the MAS was elected in late 2005, Bolivia’s social movements ranked among the world’s most radical, with defiant resistance traditions dating from the Spanish invasion, and particularly honed since they played a critical role in the 1952 middle-class led Revolution.

“Now it’s our turn” was commonly heard in MAS’s early years. To be sure, union leaders and government employees all assumed they would share in the spoils that participating in Bolivia’s government has always brought. Morales continuously decried this tendency but never formally developed a professional public administration. Whenever a new Minister or Vice-Minister is appointed, s/he brings an entirely new entourage, often to offices swept clean of files and plans, typically grinding government work to a halt. Denouncing corruption could cost an employee his or her job; and administrators complained of employees who clocked in without working.9

In Morales’ first government (until 2009), MAS did not control the legislature, a constraint that slowed its reform agenda and forced it into compromises, particularly on key issues such as land reform. Even though MAS gained control of both houses of Congress in 2009, its reforms stalled after 2011 as the coalition of movements that backed it splintered into factions.

Concurrently, and partly because effective social movement opposition was absent, government expanded resource extraction as the preferred means for funding infrastructure and services, allying itself even more closely with Bolivia’s traditional elites. By 2017, the government’s original discourse of societal transformation had given way to trumpeting the newfound economic stability it had delivered. In the process, its political agenda has become more centrist, drifting away from its early commitment to communitarian socialism to capitalist growth-promoting policies.10

In February 2016, Evo Morales was narrowly defeated in a referendum on whether he could run for a fourth term. The loss is widely attributed to voter fatigue, combined with public perceptions of increased corruption and a carefully timed and largely unfounded scandal, both fueled by Bolivia’s right-wing controlled media.11 Since Evo remains the glue that holds his party together and since MAS hasn’t found a viable replacement, most likely he will run again in 2019.

And he will probably win—despite the battering the government has taken in the past two and a half years as falling oil prices have undercut Bolivia’s gas-fueled prosperity. The opposition remains divided and unable to articulate an alternative political proposal.

Nationalization

In a widely publicized ritual that unfolded every international workers’ day (May 1st) during his first six years in office, Morales nationalized one foreign controlled company after another. These measures affected the country’s natural gas fields, oil refineries, pension funds, telecommunications systems, and main hydroelectric power plants, many of which had been privatized during the 1990’s neoliberal era.12

The first and most significant takeover — Bolivia sits atop the second largest supply of natural gas in South America after Venezuela’s — was heralded as the nationalization of the hydrocarbons sector. Morales ratings shot up overnight as the state hydrocarbons firm YPFB, gutted during the 1990s, was rapidly resuscitated and contracts renegotiated with Brazil’s PetroBras and Spain’s Repsol—the two largest hydrocarbons companies operating in Latin America.

Despite vociferous protest in the international financial press, the foreign firms’ annual profits remained about the same in dollar terms,13 thanks to high commodity prices and skyrocketing natural gas exports, primarily to Brazil (which receives over a third of its natural gas from Bolivia).14

All in all, almost half of the existing 25 foreign firms negotiated new agreements, though the perceived risk of investing in Bolivia has made them cautious about new exploration.

In fact, the May Day decree was far from nationalization in the classic sense. No assets were expropriated and no companies expelled. The more socialist-oriented social movements were furious that full nationalization was thwarted, but lacked the muscle to pressure the government enough to force a more radical outcome.

By 2017, the government’s original discourse of societal transformation had given way to trumpeting the newfound economic stability it had delivered. In the process, its political agenda has become more centrist, drifting away from its early commitment to communitarian socialism to capitalist growth-promoting policies.

Royalties and taxes were boosted to 50 percent of total production, one of the region’s highest rates. Combined with other corporate income taxes, the total government take shot up to about 70 percent of production, making gas its primary income source with annual revenues jumping from $332 million before nationalization to more than $2 billion today. By 2013, YPFB accounted for 97% of the income generated by Bolivia’s publicly owned enterprises.15 Increased state revenues, in turn, led to record levels of foreign reserves, a vital buffer during the economic downturn after 2011.

In 2012, the government nationalized electricity too. Now it’s the third largest source of state revenue. The aim is to turn Bolivia into a regional energy hub by exporting electricity to its neighbors through massive investment in new hydro-electric dam construction.

In mining, historically the heart of Bolivia’s export economy, all nationalizations to date have resulted from state mining union pressure. The principal state-run mines – at Huanuni, home to some of Bolivia’s most militant miners, and Colquiri (nationalized in 2012) operate at a deficit.16

After Morales’ 2014 election victory, the MAS government announced the end of nationalizations. Rumors circulated that Morales planned to nationalize Bolivian banks, which had flourished amid the commodity boom. But doing so would mean taking on Bolivia’s traditional La Paz-based elite, a potentially dangerous move given what had happened in Santa Cruz in 2008. With no social movement pressure, discourse soon changed to increasing taxes rather than nationalizing financial institutions.17

While Bolivia is ranked by the World Bank as 149th worst country in the world to conduct business,18 it has the region’s highest rate of foreign direct investment.19 Incongruously, then, a self-proclaimed leftist government has increased dependence on foreign funding.

Indigenous rights and territory

Between 2006 and 2007, a longstanding demand of Bolivia’s indigenous movements was met when a Constituent Assembly was held in the judicial capital, Sucre. It was the most participatory and diverse national meeting the country had ever seen.

The new constitution describes Bolivia as a plurinational state with substantial indigenous autonomy and an indigenous quota in legislative bodies. Plurinationality recognizes nations within states, radically transforming the idea of the state, and implying self-determination as both a right and a practice.20 Bolivia’s constitution mandates judicial pluralism recognizing indigenous justice systems and the redistribution of land and territory.21 Indigenous groups gained considerable territory under the MAS government, continuing gains starting in the 1990s when lowland groups won collective rights to large swathes of land, though these still await formal titling.22

The right to indigenous autonomy is guaranteed. But overlapping government functions and competencies, regional variations in land tenure, cultural heterogeneity, a complex bureaucratic process, and serious contradictions within and between the constitution and subsequent laws all get in the way.23 By 2017, only one municipality, eastern Charagua, had passed through all the hoops to become fully autonomous. Critics argued that the national government has backed away from encouraging autonomy, even undermining it, particularly as local battles over extractive projects intensify.24 Since the constitution provides for ‘consultation’ rather than ‘consent’ on proposed projects– as required by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to which Bolivia is signatory– indigenous groups can’t veto state-sponsored development and resource extraction projects on their lands.25

Between 2006 and 2007, a longstanding demand of Bolivia’s indigenous movements was met when a Constituent Assembly was held in the judicial capital, Sucre. It was the most participatory and diverse national meeting the country had ever seen.

By 2017, the expansion of indigenous rights had slowed while the guarantee of prior consultation had taken a step backward.26 The main motor of change, the Pacto Unidad (Unity Pact), formed in 2004 of all the country’s principal indigenous groups, had fragmented into pro- and anti-government factions.27 With considerable MAS support, the pro-government blocs had morphed largely into rent-seeking mechanisms for securing government posts and member benefits.28 Their non-MAS counterparts were demoralized, penniless, and short on alternative proposals.

Land reform

The skewed land tenure that plagues most of Latin America goes a long way in explaining Bolivia’s persistent high inequality. The MAS government inherited a patchwork of unevenly applied attempts at agrarian reform beginning with a 1953 measure, one of Latin America’s most significant. That reform was driven by peasant land takeovers that forced the revolutionary government to break up the large highland and valley estates that kept indigenous peasants in serfdom, though the measure failed to impact the sparsely-populated lowlands.

As highland plots became smaller with succeeding generations, many peasants fled eastward, where colonization schemes granted them thousands of parcels of government-owned land. Concurrently, during the dictatorships between 1964 and 1982, some 100 million acres in the east were transferred to about six thousand friends, family members, and political associates of the military.29

Neoliberal politics introduced a different logic in the 1990s, creating private land markets for commercial holdings, a change deemed essential for agricultural modernization. This approach was combined with such measures as exempting small farmers and indigenous communities from property taxes and extending women’s and indigenous territorial rights.

After almost seven months of sustained peasant protests demanding land reform, the Morales government passed a substantial reform in late 2006. Formulated in close consultation with the five Unity Pact organizations, the ambitious new law enhances access for peasant women, expropriates underutilized lands, and permits seizures of property from landowners employing forced labor or debt peonage. In all, approximately 800,000 low-income peasants and indigenous people have benefited.30 As of August 2016, 72 percent of Bolivia’s arable land had been titled, mostly to individuals. Forty-six percent of the new titles included women’s names.31 Land tenure has transformed: the MAS government has restructured land tenure more in eleven years than governments did in the previous forty. For the first time since the Spanish Conquest, smallholders control 55 percent of all land.

These gains notwithstanding, most of the distributed land was already under government control and was not expropriated from wealthy landowners. Still smarting from the 2008 eastern uprising, the government was also forced to make concessions to agribusiness, increasingly based in soy production, permitting each business partner to own up to 12,500 acres.32

Land tenure has transformed: the MAS government has restructured land tenure more in eleven years than governments did in the previous forty. For the first time since the Spanish Conquest, smallholders control 55 percent of all land.

Reform has slowed since 2011, mainly because the Morales government’s new priority is supporting agribusiness expansion of the agricultural frontier and because rural social movements have fragmented. In 2013, to the satisfaction of Santa Cruz’ business elites, the Morales government adopted Law 337, which permits the conversion of previously illegally cleared land to agriculture.33

Decentralized, participatory mechanisms for political and economic decision-making

With the election of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s social movements expected to see participatory rather than western-style representative democracy.34 Initial discussions about how to incorporate social movements into the MAS government discarded the co-governing model– in place for four years after the 1952 Revolution– between the MNR government and the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB). During those years, COB representatives had participated in all Executive Branch meetings, successfully pushing the revolution’s most radical changes and blocking its more conservative tendencies. In the recently nationalized mines, worker control and co-management blossomed but quickly gave way to clientelism because mining union leaders lacked the technical knowledge needed to run mines and could be appointed only by the MNR, which then appropriated, manipulated and controlled them.35 Despite this failure, Fornillo (2007:2) argues that co-government survives, albeit intermittently and with varying intensity, as an important social movement demand in contemporary Bolivia.

Rather than co-government, MAS has emphasized social control based on a largely essentialist understanding of indigenous community structures mingled secondarily with socialist discourse. Still in place in some indigenous Andean communities where lines between state and civil society blur, community control includes rotating leadership and consensual decision-making.36

During the 1990s, neoliberal decentralization reforms broke the country into 311 (now 339) municipalities and granted departmental (state) governments greater autonomy and competencies. Participatory budgeting and oversight was mandated by local organizations in the new municipalities. But few of these oversight committees have proved functional since they received no training and lack the education and experience needed to fully understand regulations and governance.37 Unpaid, they are also susceptible to corruption and patronage, and women’s participation frequently has bordered on nil. MAS efforts to exert party discipline over the committees has only compounded these problems.38

During the Constituent Assembly, a social control mechanism was proposed by the Unity Pact. The idea was that social control would operate as a fourth branch of government, overseeing the other three. Justice Vice-Minister Rafael Puente described social control as “a central theme of our constitution, the birth certificate for the new country we want.”39 The 2009 Constitution mentions social control 17 times (without defining it).40 By the time the legislature modified the constitution, citizens had lost their right to “participate” in decisions. Instead, they were to be “consulted.”41

In 2013, the Law of Participation and Social Control passed. Ostensibly, grassroots organizations would now have more influence than the 1994 LPP since social control would expand to cover all three levels of government (municipal, departmental and national). The new Law posits the participation of social organizations (rather than social movements) in overseeing public institutions, though the definition of a social organization is vague (Mayorga, 2015). The government created the Mecanismo Nacional de Participación y Control Social (National Mechanism for Participation and Social Control) as part of the Ministry of Transparency.

In practice, involvement in oversight is initiated by government ministries or state entities. They get to decide which organizations are “recognized” as participants and then invite them to meetings with pre-determined agendas. In short, government’s control over the process is far-reaching (Wolff, 2017; Zuazo, 2010: 134). Funding to operationalize the law is not mandatory so such entities as the Central Bank fulfill their obligations largely by making public presentations describing their operations.42

Government control has spread in other ways too. The 2008 eastern uprising drove Bolivia’s government to create the Coordinadora Nacional por el Cambio (National Coordinator for Change, CONALCAM) to coordinate squashing the rebellion. The move gave government more control over the leadership of rural and urban organizations, and both steadily lost their independence.43 After the eastern crisis ended, the government announced in 2010 that it would reconstitute CONALCAM to channel demands from social movements, comment on proposed laws, train a new generation of leaders, and sanction leaders or movement militants who created conflict.44 In practice however, since 2011, the government has resorted to a series of Summits to solicit social movement input, a process it controls as it sets the agenda, decides who to invite, and writes up the results.45

Fernando Mayorga (2011) cautions against pigeonholing these dynamics as the polar extremes of autonomy and cooptation. Rather, he characterizes the relationship as an “unstable and flexible coalition” (Mayorga, 2011:30).

Strengthening participatory governance has proven a contradictory process in Morales’ Bolivia since the government has both extended and constricted democratic rights.46 Government-initiated referenda are more frequent than under any previous Bolivian government, a reflection of a populist political style that favors direct consultation with the ‘people.’ While the 2009 Constitution extends rights – now half the national legislature is female, for example, and indigenous and working-class participation in departmental and national legislatures has mushroomed– these have frequently succumbed to MAS party control directed from the executive branch. Overall, MAS’ political consolidation has subverted social movements’ autonomy and independence.

Strengthening participatory governance has proven a contradictory process in Morales’ Bolivia since the government has both extended and constricted democratic rights.

Worker cooperatives, ownership and self-management

Bolivia’s industrial sector has always been tiny, hampered by a small internal market and the relative poverty of the country’s consumers, centering on food processing and textiles. The textile sector was devastated by 1980s and 1990s neoliberal reforms when some 35,000 factory jobs disappeared and 120 factories closed.47

This implosion eviscerated the union movement, united under the Central Obrera Boliviana, and fostered a burgeoning urban informal economy. Since the 1980s, in fact, roughly 60 percent of city dwellers have been working informally. MAS policies failed to create more job stability—or to transform the economy more generally.48 Although union membership rates historically have been very high, they have dropped since Morales took power, further undermining the COB.49

Pressured by COB, the Morales government did take over a failing factory in 2012, creating Enatex, a state textile company. But four years later ENATEX was shuttered, a victim of poor management, inadequate marketing, and the deluge of second hand clothing from the US combined with cheap Chinese goods, both frequently entering Bolivia as illegal contraband. A weak COB broke with the government over the Enatex crisis, ending a three-year alliance that had represented a significant departure from the federation’s historic political independence.

Coops could provide alternatives to the informal economy, but Bolivia lacks a strong cooperative tradition. Formally, the largest cooperative sector is made up of the mining cooperatives, but many of these are in fact small businesses, sometimes family-run, that can be highly exploitative, even self-exploitative. Ex–factory worker and leader of the Cochabamba Water War Oscar Olivera reports: “I was involved in setting up a self-governing factory here in Cochabamba several years ago. There was absolutely no interest from the government in what we were trying to achieve.”50

Coops could provide alternatives to the informal economy, but Bolivia lacks a strong cooperative tradition. Formally, the largest cooperative sector is made up of the mining cooperatives, but many of these are in fact small businesses, sometimes family-run, that can be highly exploitative, even self-exploitative.

Anti-imperial regional integration and trade regimes

As a landlocked country with a small internal market and a government committed to increasing industrialization, Bolivia is keener than many of its neighbors on regional integration. Most of the country’s exports go to its neighbors, but almost 90% of them are raw materials, mostly natural gas to Brazil and Argentina. This relationship has propelled Bolivia’s government to prioritize trade integration with its five neighbors, rather than with Europe or the United States.

In 2008, Bolivia lost its preferential trade status (ATPDEA) with the United States after the US determined the country was not doing enough to combat drug trafficking.51 Although the small textile manufacturing sector, particularly in El Alto, was almost destroyed, overall ATPDEA’s end had only a minimal impact because the Bolivian government replaced the subsidies and Venezuela and Brazil increased their Bolivian imports.52

Initially, Evo Morales’ government showed little interest in the region’s orthodox and market-driven integration mechanisms, the Comunidad Andina de Naciones (Andean Community of Nations – CAN) and the Mercado Común del Sur (Southern Common Market – Mercosur). However, by 2014 as leftist governments began to decline in popularity, Bolivia became a full member of Mercosur.

Early on in its administration, the Morales government took another tack. It sought to break dependence and develop solidarity principles based on such concepts as Living Well and South-South cooperation, especially through the Venezuelan-initiated Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América (Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America – ALBA) and Union de Naciones Suramericanas (Organization of South American governments– UNASUR) modeled on the European Union.

ALBA is an alternative to the US- proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas, which Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina rejected in 2005, decisively asserting their independence from the US.53 Led by Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia, the alliance’s conception of integration is fiercely anti-imperialist.54 Committed to eradicating illiteracy and expanding employment, it provides preferential rates on Venezuelan oil for Bolivia, though the recent shift in the balance of power within Latin America away from left-identified governments has undermined ALBA’s influence.55

Bolivia took the lead in forming the Tratado de Comercio de los Pueblos (TCP), which complemented ALBA but was even more explicitly anti-neoliberal. However, a trade agreement along TCP lines never materialized because of the complexity of existing agreements, interference from international institutions, bureaucratic idiosyncrasies between countries, and weaknesses in the proposal itself.56

UNASUR, formed in 2007, is less anti-neoliberal and anti-imperialist than ALBA. It seeks economic and political integration by uniting Mercosur and CAN and all 12 South American states into a regional economic bloc and integrating regional infrastructure. The proposed South American Parliament is located just outside Bolivia’s fourth largest city, Cochabamba, where initial construction of its home should be completed by late 2017.

Other construction may be under way soon too. The Morales government is discussing building a trans-continental railway linking Brazil and Peru through Bolivia and is an active partner in the Infraestructura Regional Suramericana (IIRSA). Clearly, the government hopes to attract foreign investment into hydrocarbons, mining and hydro-electric power.

Coca and Cocaine

Bolivia is the world’s third-largest coca leaf producer after Colombia and Peru—a fact that has determined its international relations for 40 years now. About 75,000 indigenous peasant families, represented by powerful peasant unions, grow coca leaf. Most is for local consumption, and about a third is processed first into cocaine paste and then into cocaine. Although essential to cocaine, coca has been consumed throughout the Andes for thousands of years and figures into rituals from birth to death. An excellent source of vitamins and minerals, it also effectively relieves stomach ailments and altitude sickness.

In March 2017, the government passed two new laws related to coca. One covered coca cultivation and the other drug trafficking, legally separating the leaf from cocaine for the first time. The previous 1988 law, widely believed to have been imposed by the US, did no such thing.57 The new coca law formally authorizes the 20,000 hectares of coca leaf cultivation that has been informally permitted since 2006, ensuring that registered growers can cultivate a subsistence amount.

In drug policy, Evo Morales’ government asserted independence from the US early on. In 2008, he expelled the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and in 2013, the US Agency for International Development (US AID). Thirty years of US-funded policy had failed to stanch the northward flow of cocaine but had provoked constant conflict and human rights violations against coca growers – who occupy the lowest rung on the drugs production chain. One of Bolivia’s two principal coca regions suffered almost constant violent conflict when the US War on Drugs began in earnest during the 1990s, but this all but disappeared after 2006.

In 2009, the Morales government initiated an innovative program with European Union financing to socially control coca. Drawing on coca grower organizations’ cohesive loyalty to Evo Morales and MAS, paired with sophisticated technological monitoring, land titling, and economic development, the program helps willing farmers engage with state institutions, international entities and agencies. Growers themselves run all the associated programs. While the pioneering policy has reduced conflict to almost zero, it is not designed, nor able, to limit drug smuggling, which faces tough prescriptions under the new 2017 anti-trafficking law.58

Key to the government’s approach is promoting alternative products made from coca, such as teas, tinctures, syrup, and flours. However, even though the UN accepted Bolivia’s local consumption of coca leaf in 2013, drug-control treaties remain a huge obstacle to marketing the leaf internationally. In November 2016, Ecuador agreed to purchase coca products, but a broader international market for coca appears a long way off.

Bolivia’s social control program is considered by the Organization of American States “a best practice… (worthy of) replication,” and it is praised by the UN Office of Drug Control. Bolivia has instituted the world’s first supply-side program that broadly reflects harm-reduction principles. These recognize that drugs will never be eliminated but also that their negative impacts on individuals, families and communities can be curtailed. While the program’s success relies heavily on the MAS party’s influence over growers’ unions, the approach highlights the potential of bottom-up approaches to one of the world’s most complex and intractable problems.59

Environmental protection and the development of a culture of sustainability

The MAS government inherited an impoverished country, with little rural infrastructure, and a mandate to bring resources to the country’s poor majority. It also inherited a country where relentless resource extraction from silver to soy has bequeathed a legacy of environmental destruction so severe that local environmental organizations consider as much as a quarter of the country’s territory under immediate threat.60 As a result, the MAS government is in a seemingly endless tug of war between its oft-stated commitment to protect the environment and the pressure to expand extractive industries to fund its ambitious social and development programs.

Initiatives like the 2012 Law of Mother Earth, where Bolivia along with Ecuador grant rights to nature for the first time in world history, play well on the hustings and the international stage, but the law lacks teeth–quantifiable targets–so has never been applied substantially. This grant of rights also clashes with entrenched interests– such the $800-million soy industry, which relies almost completely on genetically modified organisms (GMOs) banned under the law.

At the 2009 Copenhagen World Climate Summit, Morales launched a passionate plea for climate change reparations for low-income countries. In 2010, Bolivia hosted more than 15,000 people at an alternative People’s Summit on Climate Change. In the same year, Bolivia’s proposal to make access to water a universal right was approved by the United Nations (UN), leading the UN General Assembly to name Morales the “World Hero of Mother Earth.”61

The difference between discourse and practice first came to a head in 2011, when the government proposed constructing a road linking the isolated northeastern lowland known as the Beni with the country’s main highway. The proposed road would run through an indigenous territory, the TIPNIS, inhabited by Moseten peoples, whose traditional way of life was already under increasing threat from expanding logging and coca cultivation. After government forces repressed an indigenous-led march, resistance to the project spread nationally, and the government was eventually forced to put the road on indefinite hold, though it is inching toward taking up the project again.

The reliance on resource extraction has only grown since the TIPNIS controversy fractured the Unity Pact and demonstrated that the government’s commitment to prior consultation with indigenous peoples is superficial. The result is that Bolivia, with the world’s seventh largest tropical forests, now suffers the highest rate of deforestation in South America. In 2015, the MAS government promulgated a law permitting hydrocarbons and mining companies to explore up to 20 million hectares, much of it in protected areas.62 Large-scale hydro-electric projects, now in the planning stages, would further the goal of turning Bolivia into a regional energy hub. Soy production has roughly doubled since Morales took office ten years ago.

Conclusions

The economic and political metamorphosis promised by MAS has been thwarted by the inherent limitations of a small landlocked country that remains the poorest in South America. Bolivia thus continues its long history of economic dependence, though increasingly the ties have shifted from western countries to Brazil and China.

While MAS’s room to maneuver has also been limited by its increased collaboration with elites, the government’s steady undercutting of the country’s once-powerful social movements that thrust it to power has further limit its capacity for transformation. Bolivia’s social movements were unrivalled by any others in Latin America’s pink-tide countries, handing MAS both a unique opportunity and challenge. With no viable rightwing opposition since 2008, MAS has squandered the opportunity for more radical transformation by co-opting social movements. By 2016, these movements were a shadow of their former selves, with leaders demoralized or working either in the government itself or in government-controlled organizations. Increasingly, clientelism has been MAS’ response to the continued demands from both social movements and party militants for state patronage.

The consequence of this interplay of forces is overdependence on a charismatic populist leader leading a weak party, an almost textbook recreation of the stereotypical Latin American caudillo. Preserving the party and its leader in power has become a central, if not the paramount, MAS goal. The dominant watchword is ‘proyectitis’ – but public works are disconnected from any overall development plan and designed mainly to garner more votes in the next election. This emphasis has given MAS-connected leaders social mobility, repeating historic patterns of political participation in exchange for spoils. As former Bolivia representative to the United Nations, Pablo Solon, puts it, “Almost no one in the MAS escaped from the corrupting influence of power.”

The economic and political metamorphosis promised by MAS has been thwarted by the inherent limitations of a small landlocked country that remains the poorest in South America.

In Bolivia’s push to catch up after 500 years of underdevelopment and poverty, sustainability has been pushed to the back burner. A few alternative initiatives – such as a solar plant outside Oruro – are under way, but don’t compare with large-scale resource extraction. Notions of a culture of sustainability and of serious environmental protection have gone by the wayside, driven by colluding state and private sector interests.

Social movements’ loss of strength impedes progressive social change – think here of the failure to maintain the mobilization that put Barack Obama into office. But in Bolivia, where political culture is based largely in the streets, this loss of momentum is devastating. Backroom deals during times when the whims of a tiny elite threatened to carry the day were often trumped by the sheer volume of angry and articulate working class and indigenous people and their middle -class allies taking to the streets.

The cautionary tale here? No matter how fractious social movements can be or how difficult government can find it to meet their demands or how challenging sustaining mobilization can be, more radical social change will not happen unless these movements are active and independent. MAS’ failure to rethink how to make politics work, how to avoid top-down and concentrated power, how to facilitate independent citizen oversight without controlling it, and how to solve the thorny dilemma of improving living standards without destroying the natural environment demonstrates the structural constraints progressive movements face in low-income countries. That failure also shows that we still have a long way to go in creating a constructive intersection between progressive governments and social movements, and more broadly civil society organizations, capable of propelling the creation of more equitable societies.

Social movements’ loss of strength impedes progressive social change – think here of the failure to maintain the mobilization that put Barack Obama into office. But in Bolivia, where political culture is based largely in the streets, this loss of momentum is devastating.

NOTES:

- 1. Zuazo, 2010. ¿Cómo nació el MAS? La ruralización de la política en Bolivia Entrevistas a 85 parlamentarios del partido. La Paz: Frederick Ebert Stiftung.

- 2. Young, Kevin. 2017. Blood of the Earth: Resource Nationalism, Revolution, and Empire in Bolivia. Austin: UTexas Press.

- 3. Makaran, Gaya. 2016 “La figura de L llunk’u y el clientelismo en la Bolivia de Evo Morales” Revista Antropologías del Sur 5: 33 – 47.

- 4. Financial times Oct 26 2015 The New Bolivia. https://www.ft.com/reports/new-bolivia?mhq5j=e3

- 5. World Bank. Bolivia’s Gini Index 199-2014. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?end=2014&locations=BO&start=1995

- 6. Weisbrot, Marc and Luis Sandoval. 2006. Bolivia’s Challenges. Center for Economic and Policy Research. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/reports/bolivias-challenges

- 7. Wolff, Jonas. 2017. Evo Morales and the promise of political incorporation: Advancements and limits. Paper prepared for the 2017 Congress of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA), Lima, Peru, April 29-May 1, 2017: p. 5

- 8. Solón, Pablo. 2016. “Algunas reflexiones, autocriticas y propuestas sobre el proceso de cambio en Bolivia” Feb 26. https://pablosolon.wordpress.com/2016/02/25/algunas-reflexiones-autocriticas-y-propuestas-sobre-el-proceso-de-cambio/

- 9. Personal communication: employees and administrators in five ministries. 2008-2016.

- 10. Achtenberg, Emily. 2016. Evo’s Bolivia at a Political Crossroad. NACLA Dec 2, 2016. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10714839.2016.1258282

- 11. Achtenberg. 2016. Ibid.

- 12. Lefebvre, Stephan and Jeanette Bonifaz 2014. Lessons from Bolivia: re-nationalising the hydrocarbon industry. Open Democracy UK. https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/stephan-lefebvre-jeanette-bonifaz/lessons-from-bolivia-renationalising-hydrocarbon-industry.

- 13. Kaup, Brent. 2010. Bolivia’s Nationalised Natural Gas: Social and Economic Stability Under Morales. London School of Economics. http://www.lse.ac.uk/IDEAS/publications/reports/pdf/SU005/kaup.pdf 2010

- 14. Página Siete. 2016. Brasil prevé bajar a la mitad la importación de gas de Bolivia http://www.paginasiete.bo/economia/2016/9/15/brasil-preve-bajar-mitad-importacion-bolivia-10959.html

- 15. Achtenberg, Emily. 2012. Nationalization, Bolivian Style: Morales Seizes Electric Grid, Boosts Oil Incentive. NACLA. http://nacla.org/blog/2012/5/10/nationalization-bolivian-style-morales-seizes-electric-grid-boosts-oil-incentives

- 16. La Razón.2017. Déficit Minero. P. A2. March 9, 2017.

- 17. Enrique Andres Pretel. 2014. Bolivia’s Morales pledges no major nationalizations in new term. Reuters. Oct. 13. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-bolivia-election-idUSKCN0I22AU20141014

- 18. World Bank. Doing Business. http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/bolivia in 2013

- 19. Johnston, Jake and Stephan Lefebvre. 2014. Bolivia’s Economy Under Evo in 10 Graphs. Center for Economic and Policy Research. http://cepr.net/blogs/the-americas-blog/bolivias-economy-under-evo-in-10-graphs

- 20. Gustafson, B., & Fabricant, N. (2011). Introduction: New Cartographies of Knowledge and Struggle. In N. Fabricant & B. Gustafson (Eds.), Remapping Bolivia: Resources, Territory and Indigeniety in a Plurinational State (pp. 1-25). Santa Fe, New Mexico: School for Advanced Research Press.

- 21. Garcés, F. (2011). The Domestication of Indigenous Autonomies in Bolivia In N. Fabricant & B. Gustafson (Eds.), Remapping Bolivia: Resources, Territory and Indigeneity in a Plural National State (pp. 46-67). Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press. Pp 50-58

- 22. Sturtevant, Chuck. 2015. Evo Morales champions indigenous rights abroad, but in Bolivia it’s a different story. Feb 27. http://theconversation.com/evo-morales-champions-indigenous-rights-abroad-but-in-bolivia-its-a-different-story-38062

- 23. Tockman, Jason and John Cameron. 2014. Indigenous Autonomy and the Contradictions of Plurinationalism in Bolivia. Latin American Politics and Society. Volume 56, Issue 3. pp. 46–69

- 24. Tockman and Cameron. 2014: 56. ibid.

- 25. Schillling-Vacaflor, Almut. 2016, Who controls the territory and the resources? Free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) as a contested human rights practice in Bolivia, in: Third World Quarterly, online first, 1-17.

- 26. Fundacion Tierra. 2014. Reflexión y Evaluación sobre Derechos y Territorios Indígenas en Bolivia. http://www.ftierra.org/index.php?option=com_mtree&task=att_download&link_id=130&cf_id=52

- 27. Garcés, 2010:93 “El Pacto de Unidad y el Proceso de Construcción de una Propuesta de Constitución Política del Estado” www.redunitas.org/PACTO_UNIDAD.pdf

- 28. Webber, Jeff. 2015. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/10/morales-bolivia-chavez-castro-mas/ OR Achtenberg. 2014. http://nacla.org/blog/2014/2/3/rival-factions-bolivias-conamaq-internal-conflict-or-government-manipulation

- 29. Urioste, Miguel. 2009. La «revolución agraria» de Evo Morales: desafíos de un proceso complejo. septiembre-octubre. Buenos Aires: Nueva Sociedad.

- 30. Bolivia Information Forum. 2016. “Ten years on: the Morales government in perspective” Bulletin #35.

- 31. Bolivia: Land Portal. Jan 2017. http://landportal.info/es/voc/regions/bolivia?page=6; Colque, Gonzalo, Efraín Tinta and Esteban Sanjinés. 2016. “Segunda Reforma Agraria” Fundación Tierra. La Paz www.landcoalition.org/sites/default/…/segunda_reforma_agraria_2da_ed.pdf

- 32. See MacKey, Lee, 2011 “Legitimating Foreignization in Bolivia: Brazilian agriculture and the relations of conflict and consent in Santa Cruz, Bolivia”. Paper presented at the International Conference on Global Land Grabbing 6-8 April. www.iss.nl/…/23_Lee_Mackey.pdf

- 33. Ormachea S., Enrique, and Nilton Ramírez F., 2013 “Políticas agrarias del gobierno del MAS o la agenda del “poder empresarial-hacendal” La Paz: CEDLA.

- 34. Komandina Rimassa, Jorge. 2011. Los poderes de control. Revista Traspatios # 2. La transformación del Estado y del campo político en Bolivia. La Paz: Plural Editores.

- 35. Fornillo, Bruno. 2007. Encrucijadas del cogobierno en la Bolivia actual. https://www.scribd.com/document/166479429/Bolivia-EL-MAS-en-El-Poder.

- 36. Revista Traspatios # 2. 2011. La transformación del Estado y del campo político en Bolivia. La Paz: Plural Editores.

- 37. Eversole, Robyn 2010 Empowering Institutions: Indigenous Lessons and policy perils, Society for International Development 10116370/10; http://www.redunitas.org/DESAFIO_Observatorio_julio2011.pdf

- 38. Martin Vogel. 2010. Constructing local democracy in Bolivia: Decentralization and rural development, Master thesis in Development Studies, Lund University.

- 39. Puente, Rafael. 2011. ¿Qué hacer para reconstituir el sujeto del proceso? Semanario La Época, 22-6

- 40. Farthing, Linda and Benjamin Kohl, 2014. Evo’s Bolivia: Continuity and Change. Austin, TX: U Texas Press.

- 41. Revista Traspatios #2; op.cit. p. 44.

- 42. Osorio, Jimmy. 2013 “La participación y el control social ahora” La Razón Sept 29 http://www.la-razon.com/suplementos/animal_politico/participacion-control-social-ahora_0_1915008539.html; Banco Central de Bolivia.2015 “Cartilla Control Social 2015” https://www.bcb.gob.bo/?q=content/cartilla-control-social-2015

- 43. Zuazo, 2010. op. cit. p. 130

- 44. Mayorga, 2011. “Movimientos sociales y participación política en Bolivia” pp. 19-41 in Isidoro Cheresky, (ed.) Ciudadanía y legitimidad democrática en América Latina. Buenos Aires: Promoteo. biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/gt/…/cheresky-cap1.pdf

- 45. Wolf, 2017. op.cit. p. 13.

- 46. Wolff, Jonas. 2017. op.cit.

- 47. Farthing, Linda. 1991. The New Underground, Report on the Americas, 25:1, 17-37.

- 48. Evia, José Luis and Napoleón Pacheco. 2010. “Una Perspectiva Económica sobre la Informalidad en Bolivia” La Paz: Fundación Millenio; Arze, Carlos. 2016. Revista fiscal 17: Una década de gobierno. ¿Construyendo el Vivir Bien o un capitalismo salvaje revista_gpfd_17_una_decada_de_gobierno_carze_opt.pdf

- 49. Webber, 2015. 0p. cit.

- 50. Author interview, April 25, 2012, Cochabamba.

- 51. Agramont, Daniel. 2010. Bolivia frente a la integración regional: desafíos y oportunidades frente a las nuevas características del regionalismo. La Paz: Frederick Ebert Stiftung. https://www.academia.edu/5312830/Bolivia_frente_a_la_integraci%C3%B3n_regional_desafios_y_oportunidades_frente_a_las_nuevas_caracteristicas_del_regionalismo

- 52. Cadot, Olivier, Ethel M. Fonseca, Seynabou Yaye Sakho. 2008. ATPDEA’s end: Effects on Bolivian Real Incomes. CREA – Université du Lausanne. https://www.unil.ch/crea/files/live/sites/crea/files/Documents/Economie%20mondiale/ATPDEA_BolivianIncomes_02.2008.pdf

- 53. Kostze, Ignacio. 2012. “Integración económica en América Latina: desafíos en el post-neoliberalismo”http://www.madres.org/documentos/doc20130123135623.pdf

- 54. Telesur. 2014. Bolivia llama a la integración regional contra arremetida estadounidense http://www.telesurtv.net/news/Bolivia-llama-a-la-integracion-regional-contra-arremetida-estadounidense-20141229-0027.html

- 55. Bolivia Information Forum. 2017. Bulletin #37.

- 56. Cusack, Asa K. 2016. ALBA, el Tratado de Comercio de los Pueblos y los obstáculos persistentes a la cooperación económica Sur-Sur en América Latina y el Gran Caribe http://www.cries.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/11-Asa.pdf

- 57. Farthing, Linda. 2017. World Politics Review. Negotiating with Growers, Bolivia forges its own approach to coca production.http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/21803/negotiating-with-growers-bolivia-forges-its-own-approach-to-coca-production

- 58. Farthing, Linda and Kathryn Ledebur. 2015. Habeas Coca: Bolivia’s community control of coca. New York: Open Society Foundation.

- 59. Grisaffi, Tom. 2017. Long Live Coca: The Political Ascent of Bolivia’s Coca Growers’ Unions. Unpublished manuscript

- 60. Farthing, Linda. 2009. Bolivia’s dilemma: Development confronts the Legacy of Extraction. https://nacla.org/article/bolivia%E2%80%99s-dilemma-development-confronts-legacy-extraction

- 61. Munoz, Kevin. 2015. Corrupted Idealism: Bolivia’s Compromise Between Development and the Environment. http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/31724-corrupted-idealism-bolivia-s-compromise-between-development-and-the-environment#a36

- 62. Though the government requires that an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) be performed in any “protected area,” in many case these assessments have become mere formalities. Hill, David. 2015. “Bolivia opens up national parks to oil and gas firms.” The Guardian, June 5. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/andes-to-the-amazon/2015/jun/05/bolivia-national-parks-oil-gas

______________________________________________

Linda Farthing is a writer and educator with 25 years experience in Latin America as a study abroad director, film field producer and journalist/independent scholar. she is co-author of three books: Impasse in Bolivia: Neoliberal Hegemony and Social Resistance (Zed, 2006), From the mines to the streets: an activist’s life (Texas, 2011), and Evo’s Bolivia: Continuity and Change (Texas 2014). She has written for the Guardian, Ms. Magazine, Jacobin, Al Jazeera and the Nation. Her most recent policy reports are Bolivia Prison Report: Marginal Progress and Unwieldly Challenges and Habeas Coca: Bolivia’s Community Coca Control.

Linda Farthing is a writer and educator with 25 years experience in Latin America as a study abroad director, film field producer and journalist/independent scholar. she is co-author of three books: Impasse in Bolivia: Neoliberal Hegemony and Social Resistance (Zed, 2006), From the mines to the streets: an activist’s life (Texas, 2011), and Evo’s Bolivia: Continuity and Change (Texas 2014). She has written for the Guardian, Ms. Magazine, Jacobin, Al Jazeera and the Nation. Her most recent policy reports are Bolivia Prison Report: Marginal Progress and Unwieldly Challenges and Habeas Coca: Bolivia’s Community Coca Control.

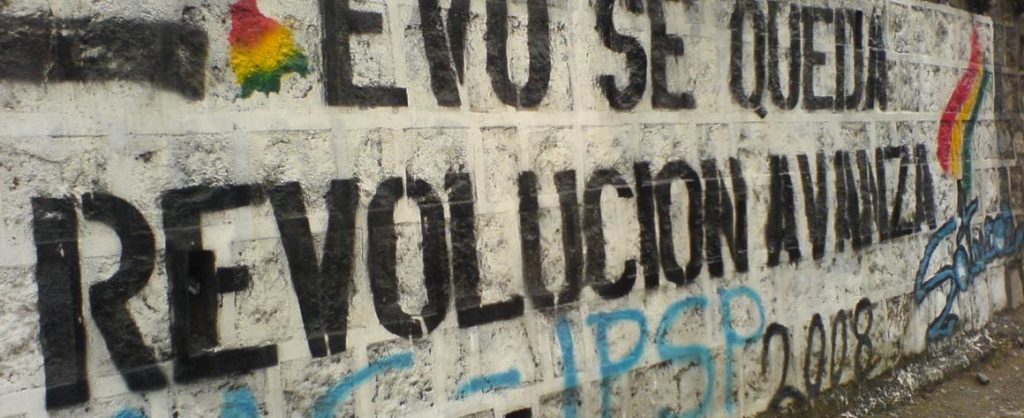

All images within the article are a copyright of Linda Farthing.

Go to Original – thenextsystem.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN:

- ‘Haiti’s Survival Is at Stake,’ Says UN Expert, Warning of Worsening Crisis

- Women's Interdepartmental Coalition of Haiti

- Biden or Trump, US Latin American Policy Remains Contemptible: Migration, Drugs, Tariffs

PARADIGM CHANGES: