Hurricane Irma Unleashes the Forces of Privatization in Puerto Rico

CAPITALISM, 18 Sep 2017

Kate Aronoff, Angel Manuel Soto and Averie Timm – The Intercept

A view of part of Parkville and the Urb Ponce de Leon and the bottom San Juan mostly without electricity on Sept. 6, 2017. Photo: Ramon Tonito Zayas/GFR Media/GDA/AP

12 Sep 2017 – Vultures circling the wreckage of Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Irma are closing in on a long-sought prize: the privatizing of the island’s electric utility.

Puerto Rico avoided the very worst of the storm, which darted just north of the U.S. territory. But it didn’t escape unscathed. Following a request from Gov. Ricardo A. Rosselló, the White House declared a state of emergency. Three people were killed and more than 1 million were left without electricity in the storm’s wake.

The fragile body responsible for that power is the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, whose executive leadership warned ahead of the storm that parts of the island could be left without electricity for up to six months. Thanks to the change in the storm’s path and a crew of dedicated line workers, Prepa, the island’s sole electricity provider, now expects most towns to have their lights back on within two weeks and full power within a month. As of Monday, more than 70 percent of homes had already gotten electricity back.

But once the lights are turned on, Puerto Rican households will face a new threat.

Watch a 360 Video on Capitalism and Colonialism in Puerto Rico

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ohnPokUQ_VY

“The Rich Port: Capitalism and Colonialism in Puerto Rico” by Averie Timm and Angel Manuel Soto. Grab and drag for a 360 view.

“[The investors] have the best sales pitch now,” Carlos Gallisá, a former consumer representative on Prepa’s board of directors, told The Intercept by phone from San Juan. “They have already started, saying that only privatization will serve the people.”

For struggling governments around the world, privatizing utilities has come to be seen as a kind of get-rich-quick scheme, offering an upfront infusion of cash to underfunded municipalities. Given Prepa’s size and that of its debt — $9 billion — it has been a long-standing target for privatizers, even before Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act last year to help rein in Puerto Rico’s mounting debt crisis. The blackout following Irma just added fuel to the fire. Days before Irma hit, Rosselló emphasized that privatization is firmly on the table, telling the New York Times that Irma “can become an opportunity or another liability.” According to a Friday report from Reorg Research, a trade publication for investors, creditors and members of Puerto Rico’s federally appointed financial oversight board have met with Prepa top brass in recent days to discuss a new “transformation plan” aimed at privatizing major aspects of the power authority. The two anonymous sources for the story claimed that the plan could go so far as “breaking up” Prepa entirely, selling pieces of the utility to various bidders.

In radio interviews after the storm, a representative from the Electrical Industry and Irrigation Workers Union (UTIER) that represents Prepa workers denounced the utility’s leadership for not sending 170 available workers out to reconnect lines and accused it of delaying restoration to build support for a corporate selloff. In the last several months, the union has made similar charges, alleging that Prepa has intentionally degraded service to prime the pump for privatization. Rumors circulated on social media, too, that Prepa’s foreboding warnings about storm-related outages were a signal for privatizers from its new leadership — installed as part of an agreement with Prepa’s creditors — that the system has reached a breaking point.

Like many other public corporations in Puerto Rico, Prepa’s leadership is wont to change with different administrations. Gallisá was elected in 2016 to serve as one of three consumer advocates on the Prepa board, only to be shunted in March when Rosselló — considered friendly to the creditors — assumed office this year. Because those position are elected, local lawmakers had to pass special legislation in order to remove Gallisá and other board members from office. “They fired everybody with the new law, and they threw us out,” Gallisá said. “They appointed members of the party in power, and that’s who are there now.”

Gallisá also suspects that one of the reasons for his ouster was that he and the other consumer advocates were outspoken about their opposition to privatization and increasing involvement from Prepa’s creditors. “At the beginning, when the governor discussed with the bondholders, the bondholders were very interested in having two or three seats [on] the board. We told them, ‘No way, they can’t have seats on the board.’”

The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (Prepa) thermoelectric plant stands San Juan, on Saturday, April 30, 2016. Photo: Erika P. Rodriguez/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Although the buzz about privatization picked up in the lead-up to and aftermath of Irma, it’s been on the agenda for years. Lisa Donahue, a consultant enlisted by Prepa to restructure the agency’s debt, floated the idea before Congress last year, and governors of Puerto Rico have discussed privatization as far back as 2012. At the end of July, four of the seven oversight board members penned a Wall Street Journal op-ed, titled “Privatize Puerto Rico’s Power”, published just after the body had rejected a restructuring proposal from Prepa. “We believe that only privatization will enable Prepa to attract the investments it needs to lower costs and provide more reliable power throughout the island,” the authors argued. “By shifting from a government entity to a well-regulated private utility, Prepa can modernize its power supply, depoliticize its management, reform pensions, and renegotiate labor and other contracts to operate more efficiently.”

By building on existing legislation, PROMESA grants the board legal authority to do it. Act 76, passed by Puerto Rico’s legislature in 2000, allows governmental bodies to bypass certain permitting processes during a state of emergency. It also allows the governor to “amend, revoke regulations and orders, and rescind or resolve agreements, contracts, or any part of them” so long as the state of emergency is in effect.

Rosselló invoked Act 76 to issue an executive order declaring a state of emergency for the U.S. territory’s energy infrastructure in January, then issued a continuation of that order in early July. Title V of PROMESA essentially extends the expedited, emergency-permitting process established under Act 76 to any of the “critical projects” outlined within it, which are required both to address an emergency and to have immediate access to private capital. Any agency that receives a critical projects proposal is required by law to put it through an expedited permitting process. The revitalization coordinator, a position created by the oversight board under Title V, must then submit a report on the project’s necessity and a recommendation to the governor, after which point the public has 30 days to comment. The revitalization coordinator is further charged with responding to those comments and relaying them to the oversight board within five days of the end of the comment period.

Under the current state of emergency, any company that submits a proposal for a critical project can bypass the permitting process ordinarily required of major projects in Puerto Rico and appeal directly to the oversight board rather than to Puerto Rican regulatory authorities or the commonwealth’s government.

“Title V is a blueprint to transform a public utility. … There are interests who were already knocking on Congress’s door to take on the issue of Prepa. When you have a body like the board, that is only accountable to Congress, companies and individuals that want to invest in Puerto Rico aren’t going to lobby the government of Puerto Rico,” said Deepak Lamba-Nieves, the Research Director for the Center for a New Economy, a Puerto Rico-based think tank. “They’re going to lobby Congress.”

As Lamba-Nieves suggested, the origins of Title V might explain why it’s so friendly to private interests and especially, to energy companies who have an interest in getting in on the ground floor of Prepa energy generation. One of its chief authors, Bill Cooper, was recruited by Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, who oversees the House committee with jurisdiction over Puerto Rico. Cooper was an adviser to Bishop, and was, while drafting PROMESA until today, the head of the Center for Liquefied Natural Gas, a trade association for LNG producers and transporters. At one point, his name was floated for the position of head of the oversight board. Commenting on that prospective appointment, one Capitol Hill lobbyist told Caribbean Business last year that “it is a done deal, Bill Cooper is going to be the executive director of the federal control board. … The fact that he has ties to the energy sector is no coincidence.”

In an interview with Politico last week, Bishop was explicit about what sorts of changes he hoped to see in the commonwealth’s energy system post-Irma: “[Prepa’s problems] are always on our radar. … They need to get a [liquefied natural gas] port there, we’ve got to get them off hard oil, but that’s not necessarily caused by the hurricane. … That’s part of the frustration we had with Prepa; they need to be able to attract more capital.”

The man tapped for that job is Noel Zamot, the revitalization coordinator hired by the oversight board in late July. Zamot, who did not respond to The Intercept’s multiple requests for comment, is the founder of a cybersecurity consultancy with a background in engineering and the military. Since coming on board, he has been soliciting critical projects proposals, almost all of which, to this point, deal with generation. Asked about Zamot’s role by Puerto Rican newspaper Metro at the end of August, Oversight Board Chairman José B. Carrión III said in a radio interview that his main task would be to “privatize the Electric Power Authority as soon as possible.”

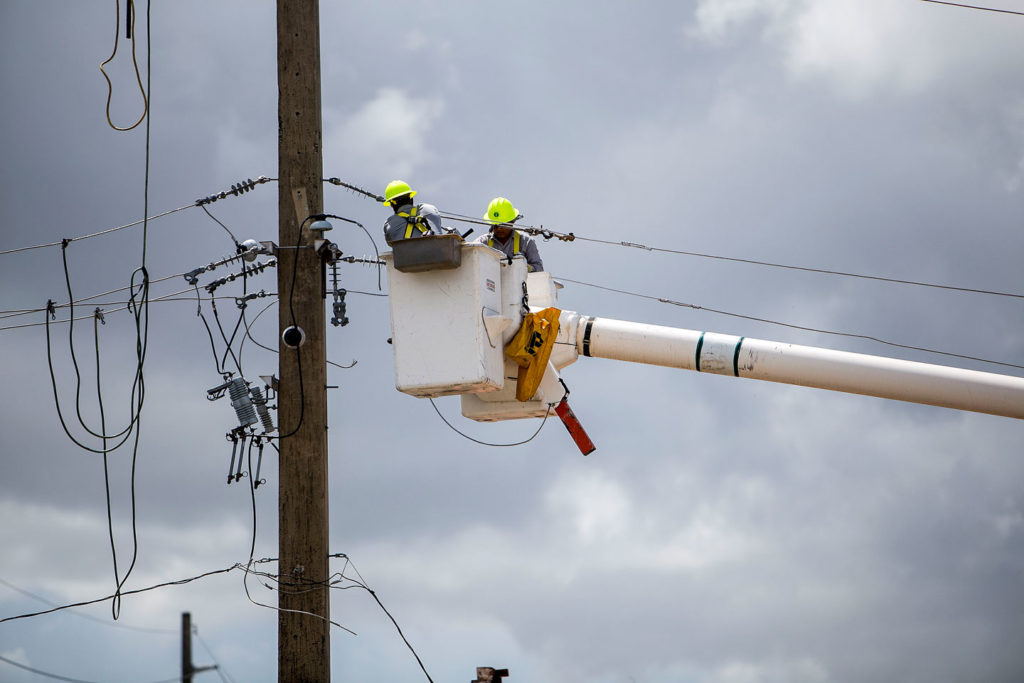

Public employees at the Electric Power Authority and Highway Patrols during and after the passage of Hurricane Irma in Puerto Rico on Sept. 7, 2017.

Photo: Xavier Garcia/GFR Media/AP

This most recent privatization push is taking place in the midst of a broader economic crisis in Puerto Rico, which is facing $74 billion of municipal debt. How did that happen? In a nutshell: Corporations flocked to the island for years thanks to a series of tax incentives, and public agencies there eagerly issued bonds to creditors who could collect a subsidy for buying them come tax season. Those incentives came under assault in the mid-90s, and, as they faded, manufacturers’ interest in the island faded too.

Due to a series of lingering and idiosyncratic tax breaks, American investors — hedge funds, mutual funds, and individuals — kept buying up bonds from Puerto Rico that were by then considered junk, without much concern for just how dire the island’s financial situation really was.

All this reached a breaking point in a 2006 recession that the global recession two years later only exacerbated. Before long, the commonwealth was having major trouble paying interest on its loans. But for reasons that remain a mystery, Puerto Rican public institutions have not been allowed to file for Chapter 9 bankruptcy since 1984. Because much of Puerto Rico’s debt is owned by a coterie of American creditors, however, the Puerto Rican government and agencies therein can still be sued in the American legal system for nonpayment.

That’s part of why hedge funds spent so much money to keep the anti-bankruptcy statute in place when debates around Puerto Rico’s debt started coming to a head in Washington post-crash. As lawmakers discussed the debt crisis, the funds poured millions of dollars into lobbying efforts and a string of front groups. One such outfit, dubbed Main Street Bondholders, was allegedly “comprised of small bondholders from across America who are committed to a policy process that returns Puerto Rico to sound financial management.”

To avoid a default — and a war between bondholders and the island’s government — Congress last July passed PROMESA. The law endows a federally appointed Financial Oversight and Management Board with broad authority to restructure the island’s debt and raise revenue. Among its powers are the ability to break union contracts, cut pensions, and take control of public assets. The legislation also established several policy protocols for how to rein in spending and fiscal management across various sectors of the Puerto Rican economy. Among the 30 percent cuts now outlined are plans to close down 75 percent of the commonwealth’s public agencies, lower the minimum wage, and privatize a slew of public corporations.

Like austerity measures elsewhere, PROMESA was passed amid tremendous controversy. Just before it went to a vote on Capitol Hill, a majority of Puerto Ricans were found to reject the creation of an oversight board. Many see it as a colonial power, one of many in the island’s long and fraught colonial relationship with a U.S. government that has severely limited Puerto Rico’s autonomy and democratic structures. It’s easy to see why: Though its authority officially circumvents that of the commonwealth governor and legislature, only one of the board’s seven members is required to be from Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rican governor is technically a member of the board but cannot vote on any of its final decisions. Protests have continued since PROMESA’s passage against various austerity measures, including a massive student strike against university privatization this past May.

Bondholders are angry about the restructuring arrangement and Prepa privatization plan for nearly opposite reasons. Unsatisfied with PROMESA and seeking faster repayment, they are now actively pressuring both the board and Puerto Rican government officials to expand cuts already slated to happen over the next several years. Those with who hold Prepa’s debt fear privatization could mean losing their collateral.

Though the drive to privatize Prepa has come largely from above, few would argue that it can continue as is. The status of the utility’s infrastructure has declined steadily over the last few decades, and many of its generation and distribution systems are dangerously outmoded. A blackout following a transmission line failure last September left half of the island without power.

“This disaster is waiting to happen. No one could say that they didn’t know the electrical system was in a state of disrepair,” says Cathy Kunkel, an energy analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, who has presented expert testimony on Prepa’s status.

A study from the Center for a New Economy found that the system loses 12 percent of its sales revenue annually to faulty billing and theft, and its leadership has historically operated without oversight and transparency. Prepa is suffering, too, from the same workforce drain as the rest of the Puerto Rican economy, where as much as 10 percent of the working-age population has emigrated in the last four years. For the utility sector, that means an aging workforce is tasked with caring for its decrepit infrastructure. That trend continuing long-term could spell disaster.

Power generation problems run still deeper. Like most other island power systems, Prepa is inordinately dependent on imported oil, which supplies about four-fifths of the island’s power and is put out to market via old and inefficient generation plants. And because most energy is produced in the south and consumed in the north, a sizable portion of what is produced gets lost along the way. A recent study commissioned by the Puerto Rican government found “a rapidly increasing generation outage rate, and customer outage levels four to five times higher than other U.S. utilities,” with authors adding that “it is difficult to overstate the levels of disrepair and operational neglect at Prepa’s generation facilities. … Prepa’s system today appears to be running on fumes and in our opinion desperately requires an infusion of capital — monetary, human, and intellectual — to restore a functional utility.”

As storms like Irma become more likely — and more likely to batter Puerto Rico — thanks to climate change, the need for an updated energy system there will only grow more urgent. “It’s pretty predictable that a Caribbean island with this sort of infrastructure would face a problem like this at some point,” Kunkel told The Intercept. “Prepa is this really disappointing example of public ownership. It’s a non-transparent entity that is not doing its job of investing in the ongoing upkeep of the generation system. It’s hard to make the argument that Prepa is some blameless entity that, had it been well-funded, would have done its job well.”

To help reform the agency in 2014, Prepa enlisted management consultant Lisa Donahue, of AlixPartners, as its chief restructuring officer. Two years and nearly $43.6 million in contracts to AlixPartners later, Prepa had cut several corners and managed to hold bondholders at bay, but was scarcely closer to a comprehensive restructuring. Donahue left the project after her sixth contract extension expired last winter. In late July, the oversight board rejected a restructuring proposal between Prepa and creditors based partially on her work, punting Prepa into default and then bankruptcy court-like proceedings outlined under Title III of PROMESA, where it now sits. Though no longer on the board, Gallisá is still an active opponent of privatization, and he hopes the court proceedings will result in the utility being able to write off a significant portion of its debt. Fearful that they could lose out on their collateral, Prepa creditors have sued the board to stop Title III proceedings.

AES Guayama Plant Treatment Plant for Ashes of the AES Company in Guayama. These ashes are not covered, at times of the passage of Hurricane Irma in Puerto Rico on Sept. 6, 2017.

Photo: Xavier Garcia/GFR Media/AP

While the board has been transparent about its desire to privatize the system, it’s less clear what it hopes privatization will look like — in part because most of those conversations have happened behind closed doors. Kunkel and Gallisá both predict that the board will move to privatize only power generation and sourcing, leaving transmission lines up to the public authority and embarking on a series of private-public partnerships.

As CNE and others argue, widespread privatization is far from the only way to whip Prepa into shape. “Prepa was created as a public good for the people of Puerto Rico. The model needs to change, but I don’t think the notion of the public good needs to wiped out,” Lambda-Nieves contended. “We’re all in favor of restructuring the debt,” he added of CNE, “but what you need to be thinking about is economic growth, not how you focus on how to appease specific bondholders.”

It’s not as if Prepa’s existing experiments with privatization have been success stories. The utility currently purchases around 30 percent of its power from two private sources, an AES coal plant in Guayama and a natural gas plant in Peñuelas, owned by the Spanish company EcoElectrica. AES sparked a major fight in the area and abroad for the plant’s dumping of coal ash, which can seep into waterways and cause a number of health problems. Post-Irma, UTIER — the Prepa utility workers’ union — denounced both of the private providers for shutting down during the storm to protect their infrastructure, straining both public providers and the unionized workforce. Were large swaths of Prepa to be privatized, it’s also likely UTIER would be disbanded.

Many suspect, as well, that further privatization would also drive up rates for customers, which has already begun to happen as part of the negotiations with bondholders.

Lambda-Nieves noted that Prepa will likely need at least some level of private investment to survive, but that without a transformation of Prepa’s governance and active regulation, nothing will change for the better. Some inroads have been made on this front already. A push from CNE and other groups led to the creation of the 2014 Energy Reform Commission, which, according to Kunkel and Lambda-Nieves, has managed to avoid becoming ensnared in the kinds of partisan political fights that have plagued Prepa.

Contra Margaret Thatcher, there are a few alternatives between Prepa’s collapse and its total privatization. CNE recently partnered with researchers at Johns Hopkins University to produce a report outlining several steps for transitioning Puerto Rico’s power grid to renewable energy, reducing the expense and volatility of an oil-based grid and driving much-needed job creation and revenue growth in the process. “With Prepa we’re not in the present. We’re stuck in the past,” Lambda-Nieves said. “It’s not just about prices, it’s about the future. Are we going to compromise the health of future generations because we have an aging and polluting power source? If there are new technologies today that can help us generate energy, why are we not using them?”

The starving, mismanagement and privatization of Prepa couldn’t come at a worse historical moment. The only real path to dramatically reducing carbon emissions in order to stave off cataclysmic climate change runs through a World-War-II-level exertion by the public sector in the energy industry. Instead, in the wake of Hurricane Irma, Puerto Rico is headed in the opposite direction.

For now, Prepa’s fate rests with the courts — and in the clouds. If the storms now brewing in the Atlantic are any indication, it’ll have bigger problems than either its creditors or the oversight board in the not-too-distant future.

___________________________________________

Kate Aronoff – karonoff18@gmail.com

Angel Manuel Soto – angel@ryot.org

Averie Timm – averie@ryot.org

Article by Kate Aronoff; video by Averie Timm and Angel Manuel Soto.

Go to Original – theintercept.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.