Prisons and Policing: Community Control Over Police – A Proposition for the USA

PARADIGM CHANGES, 27 Nov 2017

Max Rameau | The Next System Project – TRANSCEND Media Service

Systemic Challenges and Alternative Visions

Introduction

10 Nov 2017 – While it might be fair to say that the police enjoy support among the majority of the white population, the police enjoy no such support among the majority of Black people, who endure more frequent and harsher interactions with cops than whites.

To be sure, white support for the police decreases proportionately with income. That is to say, poorer whites tend to support the police less because the police interact with them differently than with their wealthier white counterparts. By the same token, support for the police among Blacks tends to increase proportionately with increases in income, wealth and other privileges. Overall and within each economic stratum, however, white support for police is higher than Black support.

Similarly, largely as a consequence of physical or sexual assaults by men against them, many women find themselves in need of protection against assaults and most often turn to the police because there are few other legal or viable options. At the same time, low-income Black, Latina and Native American women can find themselves in need of protection from assault and, simultaneously, fear being dismissed, belittled or even assaulted by the very police they turn to for protection from assault. In instances of familial or intimate partner violence, women often fear that instead of acting as a third party mediator, police will brutalize the person that they want protection from and—simultaneously—want to protect.

This tension between needing an institution for protection and living in fear of that same institution is compounded among gay, lesbian, and transgender people, who experience scorn and sexual assault at the hands of police at even higher rates than cis-gendered women. While these tensions are disproportionately visited upon under- and working-class people, they exist across class lines based on identity or perceived identity.

One’s relationship with the police, then, is not merely a function of personal preference, but is deeply rooted in realities of class, race, sex and gender, or perceived gender, identity. One’s disposition towards the police, then, is not merely an individual choice, or a trend fueled by social media, but rather a consequence of lived class and group identity experiences. The pandemic of police brutality, therefore, cannot be addressed on the individual level, but only on the structural level.

For the majority of American history, the evolution of the structures and institutions of policing occurred not just outside of the participation of Black people, but in a manner and direction that is fundamentally antagonistic to the development of the Black community. The institution of policing in what would become the United States began as private patrols of white men tasked with capturing runaway slaves. Not incidentally, those patrols were often rewarded with the bodies of Black women. After the Civil War, slave patrols morphed into an organized government structure tasking white men with enforcing the Black Codes, a series of laws crafted to criminalize and control the population of former slaves, including any imagined infringement upon the sanctity of white women.

One’s disposition towards the police is not merely an individual choice, or a trend fueled by social media, but rather a consequence of lived class and group identity experiences.

The police are not simply here to stop crime and make our neighborhoods safe. The police as an institution with a defined role in society cannot be properly understood outside of the context of class, race, and gender.

Black Communities as a Domestic Colony and Police as an Occupying Force

In his groundbreaking 1967 “Where do we go from here?” speech, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. argued that beyond the laws and customs of segregation, “the problem that we face is that the ghetto is a domestic colony that’s constantly drained without being replenished.”

That same year, the seminal book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, by Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) and V. Charles Hamilton forcefully argued that Blacks “stand as colonial subjects in relation to the white society. Thus institutional racism has another name: colonialism.”

While traditional colonies are lands geographically distant from the controlling metropole—think of African or ‘new world’ colonies and their European metropole—the primary aspects of colonialism are not distance, but exploitation and oppression.

Majority Black communities in counties or cities are forcefully segregated and provide advantages for those in power and those who identify with that power. These communities are sources for cheap labor in factories or government jobs. They serve as a dumping ground for cheap or unsafe products, such as the meat no longer good enough for nice neighborhoods, used clothing that can be resold instead of trashed, and housing that turns a profit without the need for repairs. They provide the functional equivalent of raw materials in the form of ‘customers’ in for-profit prisons or as bodies to justify government contracts in health, social services, or a number of other sectors. And the residents of Black communities provide the powers-that-be and middle class white communities with an eternally useful bogeyman for any range of social ills.

In form and in function, Black communities are a domestic colony inside of the United States. If Black communities are a domestic colony, then that colonial relationship of exploitation and oppression is maintained by an occupying force: the police.

The harsh reality is that the relationship between US police forces and residents of low-income Black communities more closely resembles that of the US army and citizens of Iraq or Afghanistan than of the police and residents of wealthy majority white gated communities. In both ghettos and invaded countries, residents fear—even hate—the occupiers, but have no say in how that force carries out its mission to ‘protect’ them. In both instances, the job of the occupying force is to defend business assets from poor people. Most telling, when cops or soldiers murder a colonial subject, the entire occupying force protects their own, the media demonizes the dead while humanizing the murderer, the colonial government protects their armed representative from any semblance of justice, and citizens of the metropole, who benefit from this colonial relationship, rally in support of their troops.

In form and in function, Black communities are a domestic colony inside of the United States.

In practice, the police serve as a hostile occupying force, enforcing the colonial status of Black communities in America. The undemocratic nature of policing undermines the ambitions of Black and other communities to exercise self-determination.

Because colonial occupation is inherently unjust, attempts to reform the occupation is inherently futile. This is why proposed “solutions” like community relations boards are fundamentally flawed.

Working at peak effectiveness, community relations boards help the occupiers better communicate the terms of occupation with the occupied. When granted teeth, civilian oversight boards help insure that the occupiers adhere to the rules of occupation established by the occupiers. Even if all police were properly trained to the highest standard imaginable, the result would be an occupation by a well-trained force.

End the Occupation and Shift Power

Virtually all theories of democracy and laws governing international human rights concur that functional democratic institutions must be firmly grounded in the informed consent of the governed. By definition, however, no people grant consent to colonization or occupation. In practice, Black people in America have never been afforded the opportunity to grant consent to an armed force empowered to stop, detain, arrest, and even take the life of members of our community.

This historic moment calls for something more significant than additional training or even civilian oversight boards.

In the face of protests against police brutality and abuse, the real question, then, is not about community relations, civilian oversight, appropriate levels of training, or even well-intentioned slogans. The core issue is one of democratic power. For all of the complexities of this time in history—and there are many complexities—the underlying issue is one of power.

The fundamental function of police in any society is to enforce the will and mores of those in power, whether that will is formally encoded in law or informally ingrained in social custom. Because they are the enforcement wing of the system, any campaign whose primary objective is to convince the police to disobey the will of those in power—to disobey their boss—and, instead, adhere to the wishes of those with no power, is not only illogical, it is doomed to fail.

The only way the police can represent and enforce the interests of the Black community—rather than the interests of outside colonial powers—is to shift power so that the Black communities have power over their own police departments. This historic moment calls for something more significant than additional training or even civilian oversight boards. We must fight for Community Control over Police.

Community Control over Police

Community Control over Police is both a principle of democratic self-determination and an objective of a social movement determined to end abusive practices that are inevitable in the context of colonial domination. However, while most support the concept of local democratic rule, that abstract idea must be converted into concrete proposals around which the Black community, and the broader social justice movement, can coalesce.

Ending the rampant abuses at the hands of police, and the criminalization of entire segments of the population to feed the prison industrial complex, is entirely dependent upon the creation of institutions and mechanism that enable low-income Black communities to control the priorities, policies, and practices of the armed forces patrolling their neighborhoods.

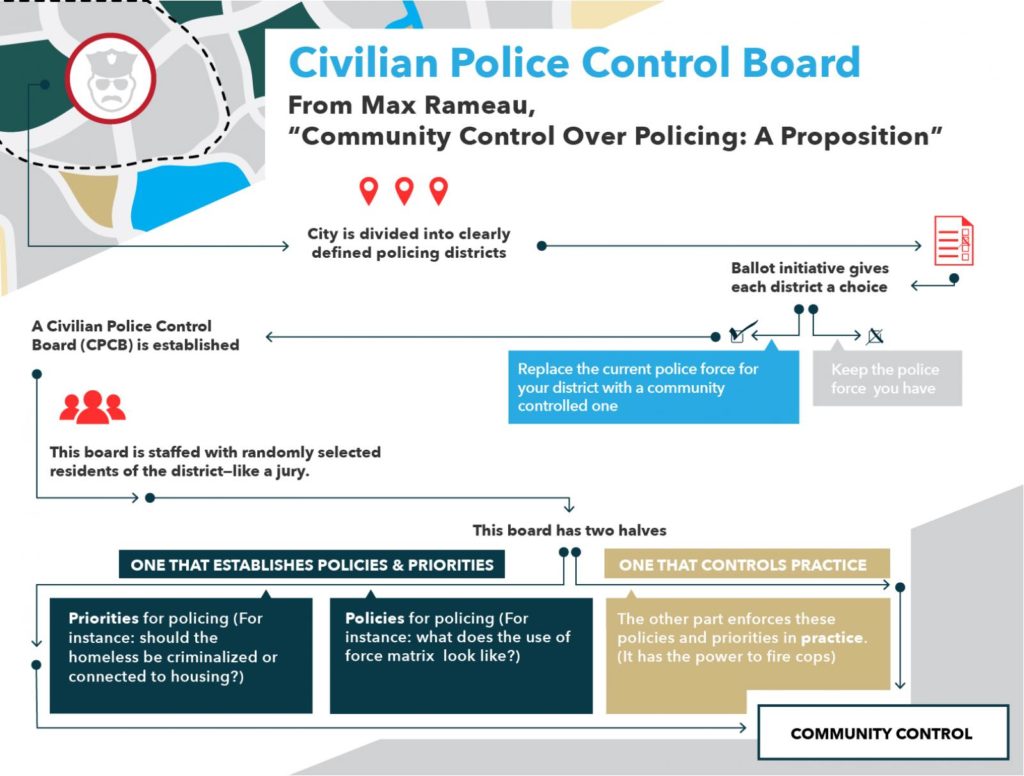

The drive towards Community Control over Police begins by organizing the target city (county or town) into clearly identified policing districts. These districts can be identical to existing commission districts, wards or other political boundaries, or can be drawn up entirely from scratch. The districts should be physically, economically and socially contiguous, enabling Black communities to have their own policing district or districts.

Once each district is delineated, the next phase is to launch a Community Control over Police ballot initiative, wherein each policing district faces a choice: keep their existing police department or start their own. While the rules for launching a ballot initiative differs from one locale to the next, the overall objective is the same in that each community or section of the city has the right to vote for the police department they want.

The process is identical to voting for commissioners, council members or alderpersons for single member districts. Voters in each district receive unique ballots that apply only to their district. Residents of District 1, for example, have no say in the determination of residents in District 5. Residents of the two districts can reach identical or opposing conclusions and one will have no impact on the other.

Do you like how your local police treat you and your neighbors? Vote to keep them. Do you think the police are unfair to you and your neighbors? Vote them out. Both voices can prevail without infringing upon the aspirations of the other.

For the first time, people will have a direct say in who has the right to carry a gun, detain, arrest, and use force in their community in the name of the state. For all of the controversy surrounding this proposal, there are few clearer examples of democracy in action. As such, this is a contest all sides of the debate should be eager to wage.

Do you believe Black communities support the police? Great! This is the chance to prove it and temper the voices of dissent. Do you believe Black communities want self-determination? Great! This is the chance to offer a direct vote on an alternative, a choice never offered by the two-party system. In the end, some communities will vote out the existing police department and vote to build a new one from scratch.

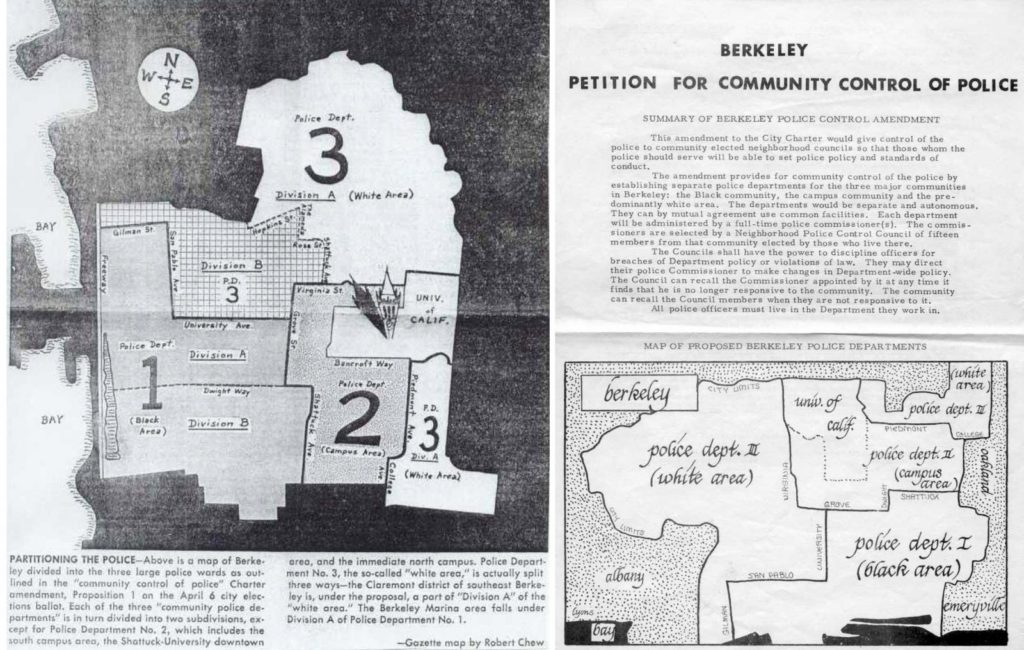

Materials from a 1970 campaign which put community control of police on the ballot in Berkeley, California.

For those who scoff at the vision of multiple agencies, it is important to note that most county police departments already work with multiple city agencies, and that many large jurisdictions already contain a plurality of different police forces operating side-by-side. For example, in addition to its own police department with jurisdiction throughout the county, Miami-Dade County, Florida has over 30 municipal police departments, at least two university departments, and a railroad police force. Beyond that, there are multiple police agencies with jurisdiction throughout the entire state of Florida, not to mention the federal departments, such as the FBI, with jurisdiction across the country. Far from an exception, the presence of multiple police departments is currently common practice throughout the country.

For the first time, people will have a direct say in who has the right to carry a gun, detain, arrest, and use force in their community in the name of the state.

Because democracy is a process and not a destination, the plebiscite on policing will reinvigorate political participation in many communities as both supporters and opponents of the local police mobilize their bases. Those organizations engaged in electoral politics and ‘get out the vote’ efforts will witness a record number of newly registered Black and Latina voters (“So let me get this straight, you are telling me I can vote out the police?”).

At the end of the vote, districts satisfied with their police will see no difference in their department. In districts that vote for a new department, the police will retreat to within its new boundaries to allow the new force to serve their new bosses.

To be clear, this vote is not to take control over an existing police department, but to establish a new one. No colony seeks control over the occupying army, they pursue an end to colonialism and realization of self-rule. In this instance, the vote is to establish a Civilian Police Control Board.

A Model: The Civilian Police Control Board

The primary institution for the exercise of Community Control over Police is the Civilian Police Control Board (CPCB).

To be clear, the power of this body is to exercise control and power over the police, not review or oversight. This is not a review board: at this stage in history, review boards represent a step backwards and one that further entrenches existing power relationships instead of upending them in favor of the oppressed. We are no longer satisfied with the ability to review abuses of our communities, we are in pursuit of the power to end those abuses.

The CPCB must be empowered to establish police priorities, set department policies, and enforce practices of the new police force.

Even though they do not make the laws, every police department, and even each district inside of a department, establishes policing priorities. For example, police districts serving downtown areas often prioritize preventing human beings without homes from damaging alleys, sidewalks, and parks with their urine, even though they have nowhere else to respond to calls of nature, and aggressively seek to arrest those who transgress these priorities. The CPCB, by contrast, can prioritize the protection of human beings without homes over the protection of sections of cement from those humans.

We are no longer satisfied with the ability to review abuses of our communities, we are in pursuit of the power to end those abuses.

Policies can include uniform specs, appropriate interactions with civilians, required levels of training around courtesy with people, and a use of force matrix. In order to enforce these policies, the CPCB must have the power to hire and fire individual police who are not serving the public interest.

With such a broad range of powers, the CPCB would likely consist of a bi-cameral board, with one half dealing with establishing priorities and policies and another with enforcement of these policies in practice.

This is Community Control over Police.

The CPCB must be comprised entirely of civilian adult human beings—not corporations or human representatives of corporations—residing in the police district. To be explicit, residing means living in, not just owning property in. And this residency requirement should be evaluated without regard to citizenship status or criminal history.

While some envision an elected board, we propose something entirely different: a board selected entirely at random among residents of the policing district.

There are two main constraints to an elected board. First, elections in the US are thoroughly corrupted by influences of corporate finance on one side and two party electoral politics on the other. Even if multiple communities were to win control over their police, it is not difficult to imagine that after one or two election cycles, your local CPCB would be a corporate board brought to you by [ insert name of powerful corporation here ]. For this board to shift power, instead of becoming another institution to maintain power, it must break through the limitations of electoral corruption.

Second, even elections with minimal levels of corporate or party influence, still occur in a social context. In this social context, elected officials are disproportionately white, male and wealthy—the exact population with the highest level of support for the police. We must devise democratic systems that encourage active participation from those least likely to engage, not those most likely to benefit.

Sortition—government by random selection—is the best way to ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to exercise power. The rich and poor, straight and gay, male and female, white and Black all have an equal shot at making decisions through random selection. If we believe that democracy is for everyone, then random selection of officials is the best way to ensure each person can exercise power.

Not incidentally, there are numerous studies on sortition, including a few theories that suggest the practice would instill better government in Washington, DC than the current practice of corporate elections.

However, for those with deep reservations about allowing randomly selected people to judge police or engage on this level of decision making, we are willing to meet you halfway. We are prepared to concede the point, and publicly support the position that ‘randomly selected’ people are not qualified to make these decisions and work to find a viable alternative that does not involve unqualified randomly selected individuals.

Right after we empty the prisons.

Guilt and innocence, imprisonment and freedom, even life and death are determined by unqualified randomly selected individuals that we call ‘jurors.’ Anyone who is not qualified to determine how their taxes are used to arm officers of the state or to decide if those officers have behaved inappropriately towards the people they serve, cannot possibly be qualified to determine if someone represented by an overworked public defender or prosecuted by an unscrupulous district attorney is guilty or innocent in a case with any level of complexity. Empty the prisons and we will work together on a better system for both.

Randomly selected board seats, refreshed on a regular basis, make subversion of the democratic process virtually impossible. Special interests would be forced to bribe entire communities in order to assure some level of voting pattern stability. If bribery is special treatment or rewards for the official in question, randomly selected board members would compel the corrupting force to provide special treatment for every adult in the given community, an act which more closely resembles a perk or amenity than bribery. Kind of like a neighborhood pool or rec center.

Equally as important, the job of ‘qualifying’ community members for board service will fall to social justice organizations. Building robust and wide reaching political education and leadership development programs will make community organizing relevant like never before as we attempt to reach the next board member before their appointment. The person with the deciding vote on the priorities of the police might be the undereducated high school dropout who hangs out near the corner store most of the day. In order to get justice, we would have to politically educate and organize our entire community.

Vision

This movement moment, in which people are rising up against police abuse, presents this generation with a unique historic opportunity to shift powers on numerous levels.

The fight for Community Control over Police has the potential to remove us from the indignity of having to manage the public relations aspects of colonial occupation. A Community Police Control Board holds the potential to not only shift power into the hands of the Black community, but to transform the very definition of power itself. The levers of power will no longer be protected behind velvet ropes, with guards ensuring the exclusive nature of the club by checking for education, diction, and money to make sure only the ‘right’ people get close. Every member of the community will have the power to decide how the armed force of the neighborhood is supposed to act.

Once we are able to secure Community Control over Police and ensure that entire communities are empowered to exercise such control, we will be free to re-imagine and re-envision the very nature of policing itself.

We suspect that this vision, and its implementation, might be so radically different and unrecognizable from what we today call ‘policing,’ that we just might be forced to rename the institution.

Imagine, a low-income Black community with 100 full time, paid community workers with sophisticated communications equipment, access to government information, and even vehicles. Now imagine those community workers operating under the control of low-income Black women who form the majority of the control board. By unleashing our power and creative energy, we can build a new vision of what police can do to truly serve and protect our communities.

We suspect that this vision, and its implementation, might be so radically different and unrecognizable from what we today call ‘policing,’ that we just might be forced to rename the institution.

But to get there we must fight for power. We must fight for Community Control over Police.

_____________________________________

Max Rameau – Haitian born Pan-African theorist, campaign strategist, organizer, and author. After moving to Miami, Florida in 1991, Max began organizing around a broad range of human rights issues impacting low-income Black communities, including Immigrant rights (particularly Haitian immigrants), economic justice, LGBTQ rights, voting rights, particularly for ex-felons and police abuse, among others. As a result of the devastating impacts of gentrification taking root during the housing “boom,” in the summer of 2006 Max helped found the organization which eventually became known as Take Back the Land, to address ‘Land’ issues in the Black community. In October 2006, Take Back the Land seized control of a vacant lot in the Liberty City section of Miami and built the Umoja Village, a full urban shantytown, addressing the issues of land, self-determination and homelessness in the Black community. more

Max Rameau – Haitian born Pan-African theorist, campaign strategist, organizer, and author. After moving to Miami, Florida in 1991, Max began organizing around a broad range of human rights issues impacting low-income Black communities, including Immigrant rights (particularly Haitian immigrants), economic justice, LGBTQ rights, voting rights, particularly for ex-felons and police abuse, among others. As a result of the devastating impacts of gentrification taking root during the housing “boom,” in the summer of 2006 Max helped found the organization which eventually became known as Take Back the Land, to address ‘Land’ issues in the Black community. In October 2006, Take Back the Land seized control of a vacant lot in the Liberty City section of Miami and built the Umoja Village, a full urban shantytown, addressing the issues of land, self-determination and homelessness in the Black community. more

Go to Original – thenextsystem.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.