I and Thou: Philosopher Martin Buber on the Art of Relationship and What Makes Us Real to One Another

INSPIRATIONAL, 26 Mar 2018

Maria Popova | Brain Pickings – TRANSCEND Media Service

“The primary word I–Thou can only be spoken with the whole being. The primary word I–It can never be spoken with the whole being.”

“Relationship is the fundamental truth of this world of appearance,” the Indian poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore — the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize — wrote in contemplating human nature and the interdependence of existence. Relationship is what makes a forest a forest and an ocean an ocean. To meet the world on its own terms and respect the reality of another as an expression of that world as fundamental and inalienable as your own reality is an art immensely rewarding yet immensely difficult — especially in an era when we have ceased to meet one another as whole persons and instead collide as fragments.

“Relationship is the fundamental truth of this world of appearance,” the Indian poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore — the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize — wrote in contemplating human nature and the interdependence of existence. Relationship is what makes a forest a forest and an ocean an ocean. To meet the world on its own terms and respect the reality of another as an expression of that world as fundamental and inalienable as your own reality is an art immensely rewarding yet immensely difficult — especially in an era when we have ceased to meet one another as whole persons and instead collide as fragments.

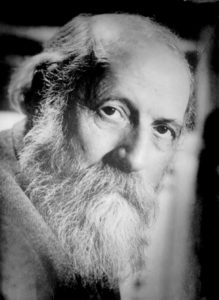

How to master the orientation of heart, mind, and spirit essential for the art of sincere and honorable relationship is what philosopher Martin Buber (February 8, 1878–June 13, 1965) explores in his 1923 classic I and Thou (public library) — the foundation of Buber’s influential existentialist philosophy of dialogue.

Three decades before Buddhist philosopher Alan Watts cautioned that “Life and Reality are not things you can have for yourself unless you accord them to all others,” Buber considers the layers of reality across which life and relationship unfold:

To the man the world is twofold, in accordance with his twofold attitude.

The attitude of man is twofold, in accordance with the twofold nature of the primary words which he speaks.

The primary words are not isolated words, but combined words.

The one primary word is the combination I–Thou.

The other primary word is the combination I–It; wherein, without a change in the primary word, one of the words He and She can replace It.

Hence the I of man is also twofold. For the I of the primary word I–Thou is a different I from that of the primary word I–It.

In consonance with poet Elizabeth Alexander’s beautiful insistence that “we encounter each other in words… words to consider, reconsider,” and with bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s conviction that words confer dignity upon that which they name, Buber adds:

Primary words do not signify things, but they intimate relations.

Primary words do not describe something that might exist independently of them, but being spoken they bring about existence.

Primary words are spoken from the being.

If Thou is said, the I of the combination I–Thou is said along with it.

If It is said, the I of the combination I–It is said along with it.

The primary word I–Thou can only be spoken with the whole being.

The primary word I–It can never be spoken with the whole being.

[…]

Every It is bounded by others; It exists only through being bounded by others. But when Thou is spoken, there is no thing. Thou has no bounds.

When Thou is spoken, the speaker has no thing; he has indeed nothing. But he takes his stand in relation.

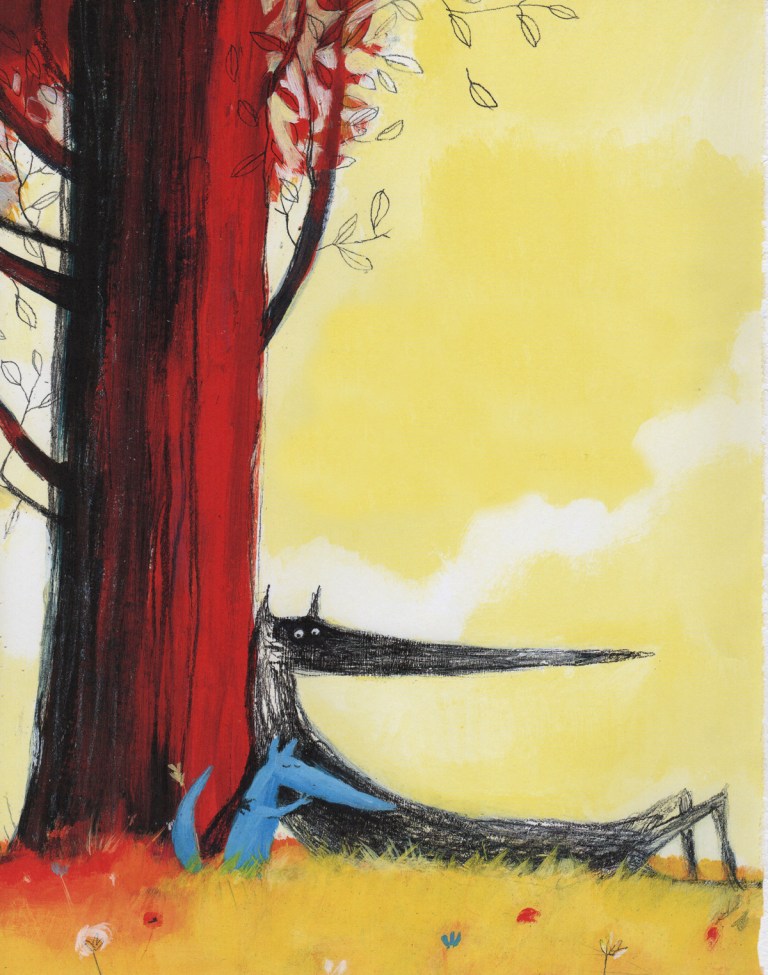

Art by Olivier Tallec from Big Wolf & Little Wolf — a tender tale of transformation through relationship.

Each battery, Buber argues, has a place and a function in human life — I–It establishes the world of experience and sensation, which arises in the space between the person and the world by its own accord, and I–Thou establishes the world of relationship, which asks of each person a participatory intimacy. Thou addresses another not as an object but as a presence — the highest in philosopher Amelie Rorty’s seven layers of personhood, which she defines as “the return of the unchartable soul.” Buber writes:

If I face a human being as my Thou, and say the primary word I–Thou to him, he is not a thing among things, and does not consist of things.

Thus human being is not He or She, bounded from every other He and She, a specific point in space and time within the net of the world; nor is he a nature able to be experienced and described, a loose bundle of named qualities. But with no neighbour, and whole in himself, he is Thou and fills the heavens. This does not mean that nothing exists except himself. But all else lives in his light.

Buber offers a symphonic counterpoint to the presently fashionable fragmentation of whole human beings into sub-identities:

Just as the melody is not made up of notes nor the verse of words nor the statue of lines, but they must be tugged and dragged till their unity has been scattered into these many pieces, so with the man to whom I say Thou. I can take out from him the colour of his hair, or of his speech, or of his goodness. I must continually do this. But each time I do it he ceases to be Thou.

[…]

I do not experience the man to whom I say Thou. But I take my stand in relation to him, in the sanctity of the primary word. Only when I step out of it do I experience him once more… Even if the man to whom I say Thou is not aware of it in the midst of his experience, yet relation may exist. For Thou is more that It realises. No deception penetrates here; here is the cradle of the Real Life.

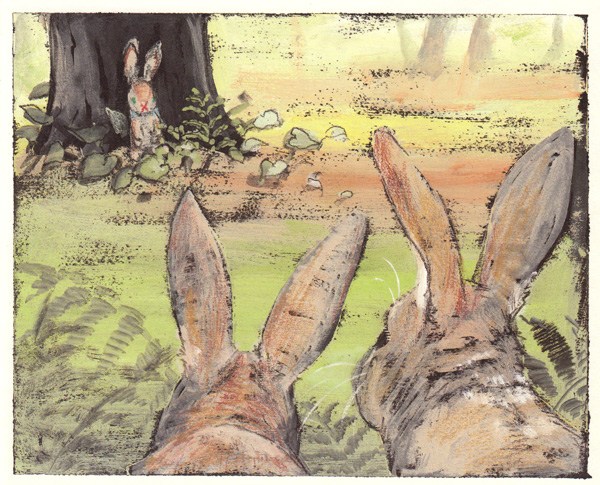

“Real isn’t how you are made… It’s a thing that happens to you.” Illustration for The Velveteen Rabbit by Japanese artist Komako Sakai.

To address another as Thou, Buber suggests, requires a certain self-surrender that springs from inhabiting one’s own presence while at the same time stepping outside one’s self. Only then does the other cease to be a means to one’s own ends and becomes real. Buber writes:

The primary word I–Thou can be spoken only with the whole being. Concentration and fusion into the whole being can never take place through my agency, nor can it ever take place without me. I become through my relation to the Thou; as I become I, I say Thou.

All real living is meeting.

[…]

No aim, no lust, and no anticipation intervene between I and Thou. Desire itself is transformed as it plunges out of its dream into the appearance. Every means is an obstacle. Only when every means has collapsed does the meeting come about.

I and Thou, translated by Ronald Gregor Smith, is a sublime read in its entirety. Complement it with physicist David Bohm on the art of dialogue and what is keeping us from listening to one another, Amin Maalouf on identity and belonging, and Ursula K. Le Guin on the magic of real human communication.

______________________________________________

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors.

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors.

Go to Original – brainpickings.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.