Triggering War

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 26 Mar 2018

Prof. Graeme McQueen – Global Research

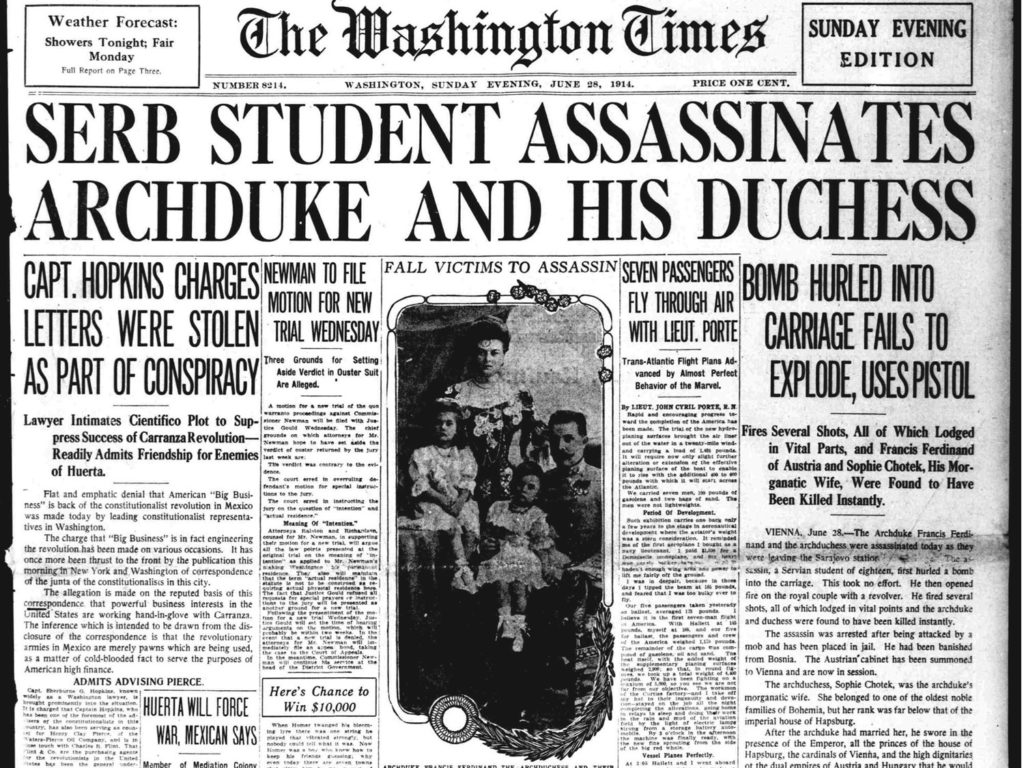

18 Mar 2018 – The assassination of Archduke Ferdinand on June 28, 1914 led to the outbreak of World War I. The Gulf of Tonkin incidents on August 2 and August 4, 1964 enabled what we call the Vietnam War. Russia-gate, Novichok, Eastern Ghouta, False Flags too?

As we watch Western governments testing their opponents – today Iran, the next day the DPRK, and then Russia and China – we hold our breaths. We are waiting with a sense of dread for the occurrence of a catalytic event that will initiate war. Now is the time to reflect on such catalytic events, to understand them, to prepare for them.

The assassination of Archduke Ferdinand on June 28, 1914 in Sarajevo led to the outbreak of World War I. The Gulf of Tonkin incidents on August 2 and August 4, 1964 enabled what we call the Vietnam War.

Both events were war triggers. A “war trigger”, as I am using the term, is an event that facilitates an outbreak or expansion of hot war–that phase of the war system in which active killing takes place.

War triggers can lead affected populations to cast aside their critical faculties and their willingness to dissent from government narratives. They can also disable moral values and ideological commitments. At the outbreak of World War I the peace movement, the women’s movement and the socialist movement were all shattered.

While there is debate among scholars today about the extent of the frenzy in Europe as World War I began, it is difficult to dismiss sophisticated eyewitnesses such as Rosa Luxemburg (image on the right), who referred to what she saw as:

“mad delirium”; “patriotic street demonstrations”; “singing throngs”; “the coffee shops with their patriotic songs”; “the violent mobs, ready to denounce, ready to persecute women, ready to whip themselves into a delirious frenzy over every wild rumour”; “the atmosphere of ritual murder”. (Luxemburg, 261)

What Luxemburg described was a subjective state produced by a successful war trigger, in which a population becomes extremely lethal as it readies itself to rush at its foe while simultaneously battering anyone in its own ranks that dares to dissent.

Luxemburg herself dared to dissent. This led to two and a half years in a German prison cell. During this time she wrote the Junius Pamphlet, criticizing Europe’s socialist leaders for having been captured by the spirit of war, and pointing to the consequences of their folly:

“the cannon fodder that was loaded upon the trains in August and September is rotting on the battlefields of Belgium and the Vosges…Cities are turned into shambles, whole countries into deserts, villages into cemeteries, whole nations into beggars, churches into stables; popular rights, treaties, alliances, the holiest words and the highest authorities have been torn into scraps”. (Luxemburg, 261-2)

Luxemburg’s anger had a solid basis in what has become known as “the August madness” that struck Europe. For example, on August 3, 1914, when the war had just begun, the following call went out to university students from the most senior officials in the Bavarian universities:

“Students! The muses are silent. The issue is battle, the battle forced on us for German culture, which is threatened by the barbarians from the East, and for German values, which the enemy in the West envies us. And so the furor teutonicus bursts into flame once again. The enthusiasm of the wars of liberation flares, and the holy war begins”. (Keegan, 358)

In response to this hysterical appeal, the German university students volunteered in large numbers. Untrained, they were thrown into battle. In the space of three weeks 36,000 of them were killed.

Germany was not unique, of course, in its vulnerability. Randolph Bourne, in an unfinished essay generally known as “War is the Health of the State”, described what he saw somewhat later in the United States as that country flipped from anti-war to pro-war and joined in the global disaster. He observed that once the executive branch had made the decision to go to war the entire population suddenly changed its mind. “The moment war is declared… the mass of the people, through some spiritual alchemy, become convinced that they have willed and executed the deed themselves.”

Therefore, the people, “with the exception of a few malcontents, proceed to allow themselves to be regimented, coerced, deranged in all the environments of their lives, and turned into a solid manufactory of destruction.”

It is true that war madness of the kind that accompanied WWI has been less common in the years since then, partly because that war turned out to be an unprecedented catastrophe. But I believe it is entirely wrong to think that in today’s era of high technology and digitalized war the arousing of the spirit of war in a population is no longer sought or needed. A highly influential analysis of American Vietnam War strategy, carried out by one Col. Harry Summers, concluded some years ago that a chief cause of the US downfall was the failure of leaders to arouse their population’s emotions. The American people, said Summers, had been forced to fight that war “in cold blood”, which they found intolerable. In fact, this failure to arouse the war spirit was taken by many US analysts to have led to the “Vietnam syndrome” – a reluctance to intervene in the affairs of other countries militarily. This was a timidity unsuitable, they felt, for an imperial power.

One of the purposes of the September 11, 2001 operation, in my view, was precisely to change that situation – to arouse intense feelings of unity, aggression and support for government in order to banish once and for all the Vietnam Syndrome and to launch with great energy the new global conflict formation (the “War on Terror”) so that the 21st century, with the military leading the way, would become another American Century.

Still, war triggers are not all the same, and we need to create categories. We can distinguish three broad types: accidental war triggers, managed war triggers and manufactured war triggers.

An accidental war trigger is an event that triggers hot war in the absence of intention. The pressure of events, random clashes, the everyday quest to satisfy physical needs – all these may, in the absence of warlike intent, produce a war trigger. After the event occurs it may lead, again without conscious plotting, directly to a hot and violent conflict between contending parties.

No doubt many war triggers throughout history fit the category of accidental war trigger. However, the more I have studied recent human wars the less ready I have become to promote the triggering events as accidental.

Years ago when I gave talks on war triggers I used to give the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand as an example of an accidental war trigger. True, I understood that the assassin of the Archduke did not act alone: Gavrilo Princip, the young Serbian nationalist, was certainly not a “lone wolf”; he was one of several armed men stationed along the route of the Archduke’s carriage, and although he was committed to this plan it is also pretty clear that he was deliberately used by a group with high-level connections to carry out the assassination. But I felt that the planners were unlikely to have sought the large-scale conflagration they ended up getting, and I was impressed by the variety of elements in the “Balkan cauldron” that seemed to defy rational planning. Likewise, I was impressed by the numerous systemic factors operative in the wake of this event that led to a major war, ranging from a flourishing arms industry, through genuinely deluded ruling classes and entangling state alliances, to systems such as railways that gave an advantage to the first party to mobilize. All in all, I felt that non-deliberate factors outweighed deliberate factors, so I called this an accidental war trigger.

Recent reading, however, has made me less confident of this position. Especially since encountering Docherty and McGregor’s book, Hidden History: the Secret Origins of the First World War, I am inclined to reclassify the World War I war trigger as a managed trigger.

A managed war trigger is one in which a party of influence consciously acts to increase the chances of hot war, either by deliberately creating conditions where a war trigger is likely to arise, or by seizing an event after the fact and shaping it into a war trigger.

If World War I’s war trigger must be moved from accidental to managed, this increases the number of cases in this already well-stuffed category. The Pearl Harbor attack that caused the US entry into World War II was certainly managed. The factors that would increase the chances of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, thereby overcoming the US population’s resistance to entering this war, were studied and made part of a deliberate program. The Japanese advance on Pearl Harbor was consciously allowed to proceed. The declaration of war on Japan was the immediate fruit of this managed attack.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident also falls into this category. This was no accidental dustup in the Gulf of Tonkin. US leaders had created a systematic program of naval raids on the coast of North Vietnam (the DESOTO raids) intended to stimulate responses. While there is still debate about the degree to which this incident was planned, I am on the side of those who see it as highly deliberate provocation by US leaders, constructed and used to create hot war. The North Vietnamese response to the intrusion of the Maddox and the Turner Joy was remarkably mild, but it was magnified and distorted by US Cold Warriors so that it could be portrayed as “communist aggression” that required violent response.

The success of these last two managed war triggers can be seen in the record of voting in the US Congress. On December 8, 1941 there was only one vote in Congress against the declaration of war on Japan. On August 7, 1964 the House voted unanimously in favour of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, while in the Senate the vote was 88-2.

These voting statistics are sobering. The readiness of the group mind to revert to a pre-rational state—to take aggressive action with dire consequences without seeking any serious confirmation of the facts of the matter—puts humanity in a state of profound risk.

A manufactured war trigger carries the manipulation of populations even further. Here, deliberateness is extreme: it is not simply a matter of increasing the chances that this or that incident will occur, or making a mountain out of a molehill after the event. Here, those desirous of war write the script, choreograph the action, plan the output, and carry out, or subcontract, the actual event. Typically, they will also prepare to demonize and marginalize anyone who dares to challenge the narrative they present to the world.

The War on Terror is a master class in manufactured and managed war triggers. My own studies have concentrated on the two-part operation of the fall of 2001 – the September 11 airplane incidents and the immediately following anthrax letter attacks. These were manufactured war triggers, and they were successful in winning the support of both the US population and its representatives for foreign wars and restrictions on domestic civil rights.

A Washington Post-ABC poll initiated on the evening of 9/11 reportedly found that:

“nearly nine in 10 people supported taking military action against the groups or nations responsible for yesterday’s attacks even if it led to war. Two in three were willing to surrender ‘some of the liberties we have in this country’ to crack down on terrorism”. (MacQueen, 36)

Meanwhile, on September 11 cowed members of Congress fled for their lives on receiving information that a plane was headed toward the Capitol. That evening they assembled on the Capitol steps to sing God Bless America and to begin what was, in effect, their complete capitulation to those who had manufactured this war trigger.

On September 14, 2001 the Authorization for Use of Military Force was passed with a vote of 98-0 in the Senate and 422-1 in the House.

By late October members of Congress had begun to recover somewhat, and the USA Patriot Act, restricting domestic civil rights, met more opposition in the House than had the rush to war, passing by a vote of 357-66. Its fate in Senate, however, was more typical of such cases: 98 to 1.

These outcomes in Congress demonstrate the remarkable success, in the short term, of the manufactured war triggers of the fall of 2001. The effects of such operations, however, are temporary, so the perpetrators have had no choice but to continue managing and manufacturing war triggers to maintain the fraudulent War on Terror. The FBI (and parallel federal police agencies in other Western countries) busily entrap and recruit young people as fodder for the War on Terror, while in other cases False Flag attacks are carried out using wholesale invention. These initiatives have had a mixed success. For example, the official account of the Boston Marathon bombing is widely accepted despite its contradictions and absurdities; but the story of the Syrian chemical weapons attack of 2013 failed to accomplish its apparent aim of greatly expanded direct US military involvement in Syria. Likewise, sceptics of the recent claim of Russian “novichok” use in the UK are already vocal.

We would do well to remember that the on-going production of managed and manufactured war triggers takes great resources and cannot forever remain leak-proof. It carries serious risks for war planners. The successful and definitive exposure of even one of these frauds before the people of the world could affect the balance of power overnight.

Our task is clear. We must mobilize both our investigative resources and our communication resources to nullify the efforts of those who specialize in the construction and encouragement of war triggers and who wish to keep the war system robust. We lost over 100 million people to war in the 20th century. Are we really going to let this happen again?

Sources:

The Junius Pamphlet: The Crisis in the German Social Democracy, in Rosa Luxemburg Speaks, edited by Mary-Alice Waters. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1970.

John Keegan, A History of Warfare. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1993.

Randolph Bourne, “The State (‘War is the Health of the State’)”, 1918.

Col. Harry Summers, On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War. Presidio Press, 1982.

Gerry Docherty and Jim MacGregor, Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2013

Robert B. Stinnett, Day of Deceit: The Truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor. New York: Touchstone, 2001.

Graeme MacQueen, The 2001 Anthrax Deception: The Case for a Domestic Conspiracy. Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2014.

_______________________________________________

Prof. Graeme MacQueen is co-editor of the Journal of 9/11 Studies and co-author, with Johan Galtung, of Globalizing God-Religion, Spirituality and Peace, TRANSCEND University Press, 2008.MacQueen was founding director of the Centre for Peace Studies at the McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, where he taught for 30 years. He holds a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies from Harvard University and is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. MacQueen was an organizer of the Toronto Hearings on 9/11, is a member of the Consensus 9/11 Panel, and is a former co-editor of the Journal of 9/11 Studies.

Prof. Graeme MacQueen is co-editor of the Journal of 9/11 Studies and co-author, with Johan Galtung, of Globalizing God-Religion, Spirituality and Peace, TRANSCEND University Press, 2008.MacQueen was founding director of the Centre for Peace Studies at the McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, where he taught for 30 years. He holds a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies from Harvard University and is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. MacQueen was an organizer of the Toronto Hearings on 9/11, is a member of the Consensus 9/11 Panel, and is a former co-editor of the Journal of 9/11 Studies.

Go to Original – globalresearch.ca

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.