Reflections on the Cultural Construction of Reality: Assumptions, Issues, Directions

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 23 Apr 2018

Anthony J. Marsella, Ph.D. - TRANSCEND Media Service

23 Apr 2018

- There is an inherent human impulse in the human brain and body to describe, understand, and predict the world through the processing and ordering of stimuli;

- The undamaged human brain and body not only responds to stimuli, but also organizes, connects, and symbolizes stimuli; there is an effort after meaning;

- In the process and ordering of stimuli, the brain and body generate patterns of explicit and implicit “meanings,” facilitating and promoting survival, adaptation, and adjustment;

- The process and product of these neural activities are, to a large extent, culturally contextualized, generated, and shaped through sensory, linguistic, behavioral, and interpersonal practices, constituting the cultural socialization process and product;

- The storage of stimuli as accumulated life experience, in both representational and symbolic forms in the in the brain, and in external forms (e.g., books), generates a shared cognitive and affective process and product;

- Cultural continuity occurs or is challenged across time (i.e., past, present, and future) for both the person and the group;

- Individual and collective “identities” are forged through this process of change and adaptation and adjustment.

- There are dynamic (i.e., changing) variations within individual and collective identities in a given cultural context, furthering the survival, adaptation and adjustment;

- Through socialization, individual and group preferences and priorities are rewarded or punished, thus promoting and/or modifying the cultural constructions of reality (i.e., ontogenies, epistemologies, praxologies, cosmologies, ethosei, values, and behavior patterns);

- “Reality” is “culturally constructed;”

- Different cultural contexts create different realities via cultural socialization processes;

- Cultural diversity is as important for human survival, adaptation, and adjustment, as is biological diversity;

- Efforts and pressures after homogenization, conformity, and denial of diversity limit individual and collective potential and encourage risks oppression and domination.

- Definition of Culture:

- Culture is shared learned meanings and behaviors socially transferred across time to facilitate and promote individual and collective survival, adaptation, and adjustment;

- Cultures are represented (1) internally (i.e., values, beliefs, attitudes, axioms, orientations, epistemologies, consciousness levels, perceptions, expectations, personhood, identities) and (2) externally (i.e., artifacts, roles, institutions, social structures);

- Cultural milieus can be (3) transitory (i.e. situational, even for a few minutes); (4) relatively enduring (i.e., ethno-cultural life-styles, world views); and are, in all instances, (5) dynamic (i.e., subject to change and modification as a function of individual, collective, and environmental responses);

- Cultures (6) shape and construct our realities (i.e., they contribute to our world views, perceptions, orientations), including ideas, morals, and preferences.

- Cultures pursue and achieve intentions and purposes via (7) both specific and integrated sensory input processes and patterns (e.g., sensory types and patterns) yielding situational and accumulated experiences.

- In constructing shared and individual realities, (8) experiences are coded verbally, linguistically, imagistically, proprioceptively, and viscerally. Coding shapes individual and group differences by influencing ways-of-knowing (i.e., epistemology), views of human nature and being (ontologies), and behavior practices and displays (praxiology).

- Group differences in the nature of “being” in the world can be perceived as (9) variations associated with national and societal “cultures” (e.g., Japanese, Chinese, Indian, German; Latino, European, American, Indigenous).

- Cultural Change and Destruction

Culturally constructed realities resist imposed change; they do not yield well to contestations. Although adjustments can and do occur, consequences have often been associated with pernicious outcomes including the following:

- cultural confusion,

- cultural destruction,

- cultural dislocation,

- cultural collapse,

- cultural abuse,

- cultural decline,

- cultural eradication,

- cultural extinction

Culture as Term, Concept, Construct

Culture is a concept and construct. It is a word and terms. It joins thousands of other concepts among social, psychological, and behavioral disciplines, and is essential foundation for “culture” disciplines and professions. Debate regarding the power of “words” is not new. Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626) wrote:

“Men imagine that their reason governs words, whilst, in fact, words react upon their understanding; and this has rendered philosophy and the sciences sophistical and inactive. Words are generally formed in a popular sense, and define things by those broad lines which are most obvious to the vulgar mind; but when a more acute understanding, or more diligent observation is anxious to vary those lines, and to adapt them more accurately to nature, words oppose it.”

— Sir Francis Bacon, Novum Organum I, (1620), 59-60.

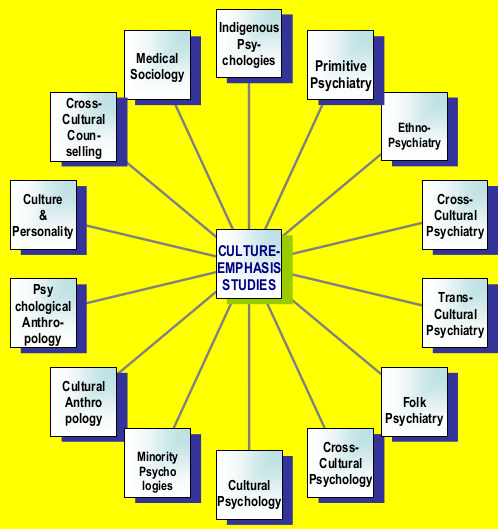

Culture Studies Disciplines, Specialties, Interests

There are many academic and professional disciplines specialties, and interests studying culture. These are displayed in Chart 1:

CHART 1: EXAMPLES OF CULTURE-EMPHASIS STUDIES,

DISCIPLINES, SPECIALTIES

There is so much more to be said, explained, debated about the concept and term culture. In today’s world, cultures have assumed ideological implications, and a contestation for dominance and control. Patience is needed. Doubt is a virtue!

__________________________________________

Anthony J. Marsella, Ph.D., a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment, is a past president of Psychologists for Social Responsibility, Emeritus Professor of psychology at the University of Hawaii’s Manoa Campus in Honolulu, Hawaii, and past director of the World Health Organization Psychiatric Research Center in Honolulu. He is known internationally as a pioneer figure in the study of culture and psychopathology who challenged the ethnocentrism and racial biases of many assumptions, theories, and practices in psychology and psychiatry. In more recent years, he has been writing and lecturing on peace and social justice. He has published 21 books and more than 300 articles, tech reports, and popular commentaries. His TMS articles may be accessed HERE and he can be reached at marsella@hawaii.edu.

Anthony J. Marsella, Ph.D., a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment, is a past president of Psychologists for Social Responsibility, Emeritus Professor of psychology at the University of Hawaii’s Manoa Campus in Honolulu, Hawaii, and past director of the World Health Organization Psychiatric Research Center in Honolulu. He is known internationally as a pioneer figure in the study of culture and psychopathology who challenged the ethnocentrism and racial biases of many assumptions, theories, and practices in psychology and psychiatry. In more recent years, he has been writing and lecturing on peace and social justice. He has published 21 books and more than 300 articles, tech reports, and popular commentaries. His TMS articles may be accessed HERE and he can be reached at marsella@hawaii.edu.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 23 Apr 2018.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Reflections on the Cultural Construction of Reality: Assumptions, Issues, Directions, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

I hope you will correlate your fine constructivist definitions with those found in my text, Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication: Paradigms, Principles, & Practices. The text defines a constructivist paradigm (in contrast to a Newtonian/Positivist one and an Einsteinian/Relativist one) and then, along with associated readings, explicitly places intercultural communication definitions and applications in the constructivist context. I welcome the company!