When Facebook Becomes ‘The Beast’: Myanmar Activists Say Social Media Aids Genocide

MEDIA, 9 Apr 2018

A young woman looks at her Facebook wall while she travels on a bus in Yangon on August 20, 2015. Facebook remains the dominant social network for US Internet users, while Twitter has failed to keep apace with rivals like Instagram and Pinterest, a study showed.

NICOLAS ASFOURI/AFP/Getty Images

7 Apr 2018 – As tens of millions of Americans come to grips with revelations that data from Facebook may have been used to sway the 2016 presidential election, on the other side of the world, rights groups say hatemongers have taken advantage of the social network to widely disseminate inflammatory, anti-Muslim speech in Myanmar.

The rhetoric is aimed almost exclusively at the disenfranchised Rohingya Muslim minority, a group which has been the target of a sustained campaign of violence and abuse by the Myanmar military, which claims it is targeting terrorists.

Human rights activists inside the country and out tell CNN that posts range from recirculated news articles from pro-government outlets, to misrepresented or faked photos and anti-Rohingya cartoons.

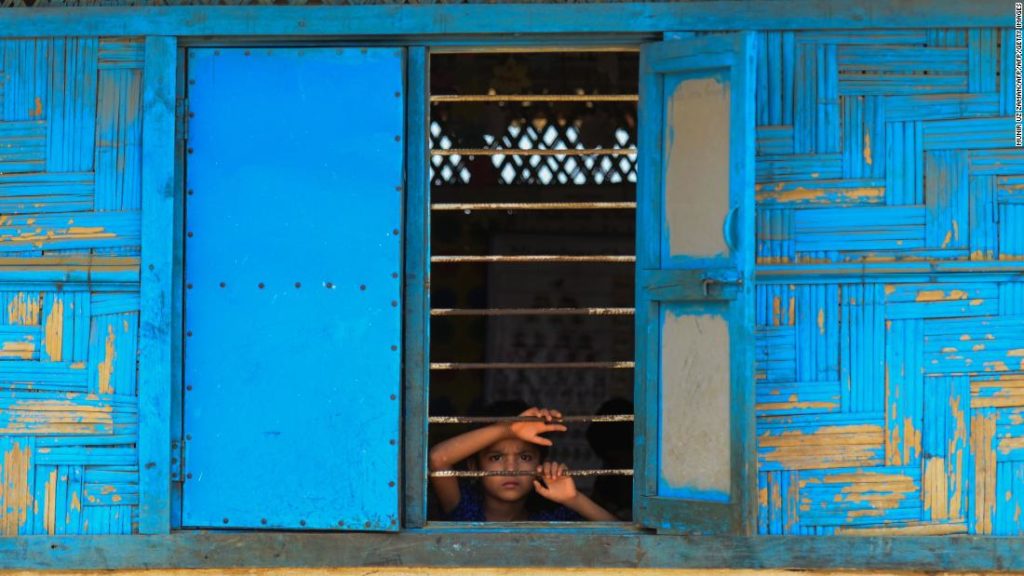

A Rohingya refugee looks out from a school window at Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh’s Ukhia district.

In response to the flood of hate-filled posts, a cross-Myanmar group of tech firms and NGOs has written an open letter to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, lambasting what they term the “inadequate response of the Facebook team” to escalating rhetoric on the platform in Myanmar.

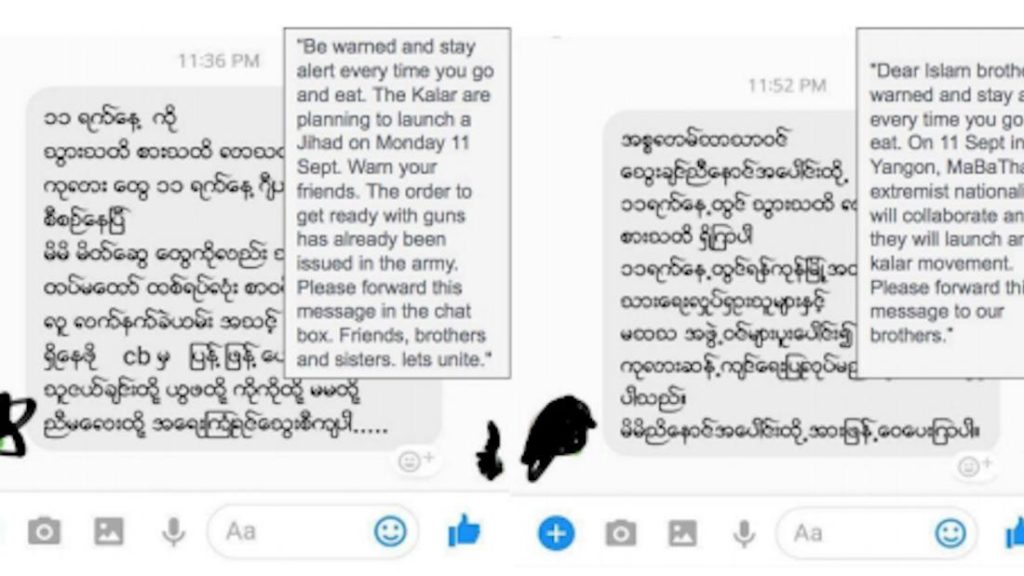

Citing conversations the group says it unearthed on Facebook’s Messenger service, which issue calls to arms against Muslims over a fabricated “jihad” planned for September 2017, it stated that the examples show “clear examples of (Facebook) tools being used to incite real harm.

Facebook Messenger conversations, screenshotted and included with an open letter to Mark Zuckerberg from Myanmar tech companies.

“Far from being stopped, they spread in an unprecedented way, reaching country-wide and causing widespread fear and at least three violent incidents in the process.”

The letter cited an interview Zuckerberg did with Vox’s Ezra Klein, in which he said Facebook’s “systems detected” the hate speech. The letter surmised that by “systems” Zuckerberg meant the signatories of the letter — third party vendors in Myanmar which, the letter admits, were “far from systematic” in their detection of hate speech.

Calling it “the opposite of effective moderation,” the group also chided Facebook for what it called a lack of proper mechanisms for emergency escalation, a reticence to engage local stakeholders and a lack of transparency.

Zuckerberg told Vox hate speech is “a real issue, and we want to make sure that all of the tools that we’re bringing to bear on eliminating hate speech, inciting violence, and basically protecting the integrity of civil discussions that we’re doing in places like Myanmar, as well as places like the US that do get a disproportionate amount of the attention.”

Sudden surge

New research suggests Facebook played a key role as extremists sought to escalate the conflict in Myanmar.

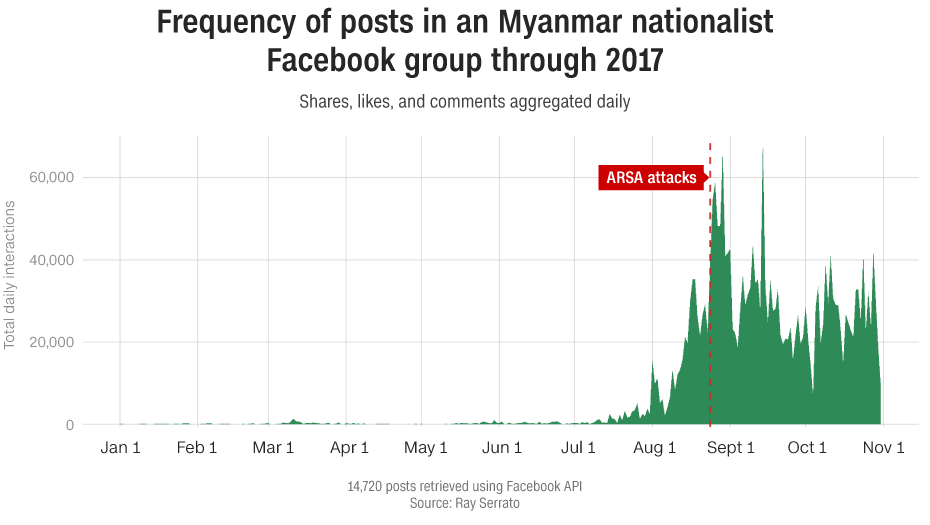

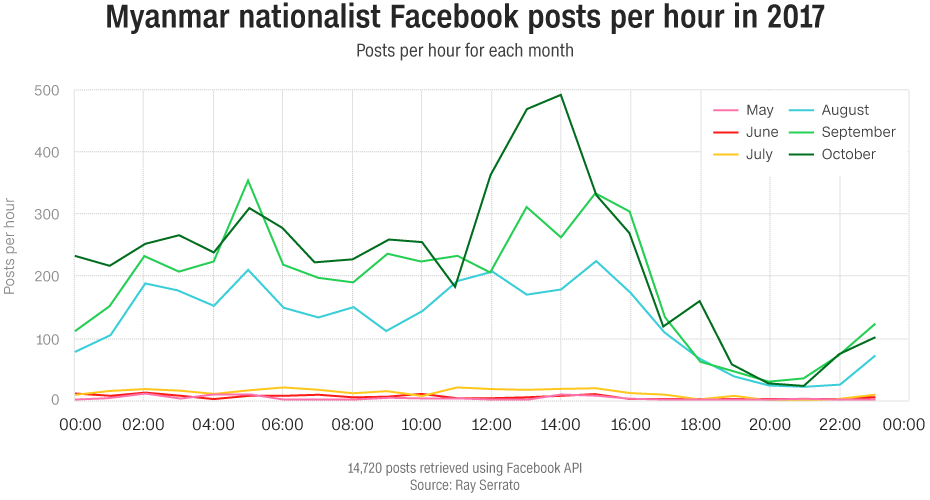

Data analyst Raymond Serrato looked at posts from Myanmar citizens over the course of 2017, determining that there was a massive spike in hate-speech posts following an August military campaign in the country’s western Rakhine state, home to the majority of the country’s Rohingya.

The campaign was initially sparked when an insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, called for an uprising — one which was easily quelled by the government.

The failed attempt led to the large-scale purge, which the UN has called “ethnic cleansing,” and a subsequent refugee crisis, which has seen 700,000 Rohingya forced from their homes and across the border into neighboring Bangladesh. Myanmar denies the intentional killing of civilians, and insists that operations targeted terrorists.

Serrato said he was “surprised by the intensity” and frequency of the anti-Rohingya posts.

“In August, when ARSA called on the Rohingya to rise up, (we were) surprised by the speed at which (anti-Rohingya voices) weaponized social media.”

Facebook has ‘turned into a beast’

In March, Facebook was accused by the UN of “substantively” contributing to the “level of acrimony” against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

Marzuki Darusman, the chair of a United Nations probe into human rights in Myanmar, said “hate speech and incitement to violence on social media is rampant, particularly on Facebook” and largely “goes unchecked.”

His colleague, the UN special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, added that “we know ultra-nationalist Buddhists… are really inciting a lot of violence and a lot of hatred against the Rohingya or other ethnic minorities.

“I’m afraid that Facebook has now turned into a beast, and not what it originally intended” to be, she said.

Instrument of ‘hate and racism’

Human rights activist Zarni, who like some in the country, goes by only one name, told CNN the platform is neutral, but “what is toxic is the state. (Lee) said Facebook has turned into a beast, (but in fact) the beasts are using Facebook.”

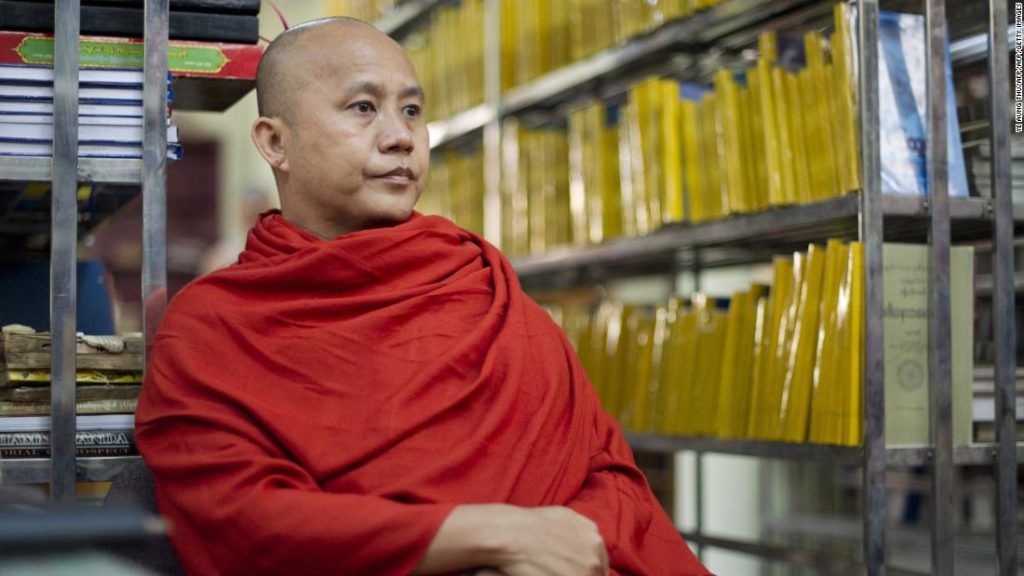

He says the main provocateurs are “operating in very powerful institutions — the military and monastic networks; the two major pillars of Burmese society.” Among the offenders, at least until his ban from the platform, was the infamous ultra-nationalist monk Wirathu.

Controversial Myanmar monk Wirathu speaking during an interview at a monastery in Myanmar’s second biggest city of Mandalay.

In 2015, he told CNN that Muslims “take many wives and they have many children. And when their population grows they threaten us.” “And,” he concluded, “they are violent.”

Thaw Parka, a spokesman for Ma Ba Tha, a Buddhist nationalist group associated with the controversial monk, says critics “cherry pick (Wirathu’s) extreme words.”

A Facebook spokesperson told Reuters it suspends and sometimes removes anyone that “consistently shares content promoting hate,” in response to a question about Wirathu’s account.

Others are not letting the social media giant off the hook. It would be “superficial” to “ignore the conflict between ethnicities,” Serrato says, “but Facebook has definitely facilitated it.”

Jes Kaliebe Petersen, CEO of Myanmar-based startup accelerator Phandeeyar, says while there is a lot of racist content shared on the platform, “there are also moderate voices that are doing good work not only countering this but spreading moderate narrative, but “get drowned out.”

New users, new problems

Myanmar’s relative callowness in engaging online is part of the reason the rhetoric has exploded, and been so influential.

The country experienced a “digital leapfrog effect,” says Petersen. “Until 2014, there was less than 5% mobile phone penetration, but overnight, SIM cards were offered for (as little as) $1.50,” allowing a much greater number of people to buy smartphones.

Myanmar has a “whole new generation of internet users, just coming to terms with what you can do online,” he says.

Facebook’s ubiquity in the country — the UN’s Darusman says, in Myanmar, “social media is Facebook, and Facebook is social media” — only serves to multiply hate speech’s virality.

Activist Sein Thein says the burden of responsibility for the online rhetoric should not fall entirely on Facebook’s shoulders, and that Myanmar’s citizens “need to be mature” when they are online.

Facebook: We’re combating hate

In order to combat the platform being used for hate speech against the Muslim minority, Facebook said it has “invested significantly in technology and local language expertise” in Myanmar following the UN accusations.

“There is no place for hate speech or content that promotes violence on Facebook, and we work hard to keep it off our platform,” a spokesperson told CNN.

The spokesperson said the company has worked with experts in Myanmar for several years to produce a community standards page for Myanmar “and regular training sessions for civil society and local community groups across the country.”

It is hard for Facebook to monitor the rise of hate speech in the country, Petersen says, partly due to language difficulties.

“There’s an intention to enforce them but it’s not being followed.” Petersen says his company, Phandeeyar, helped Facebook translate its community standards into Burmese.

In response to the March UN accusations, Myanmar government spokesman Zaw Htay said his government and Facebook are “promoting cooperation and coordination for the Myanmar people to understand the community standards of Facebook.”

On Facebook he said supporters of the Rohingya were also using social media to “spread… disinformation around the world.”

The group that sent the open letter to Zuckerberg, co-signed by Phandeeyar, urged the tech mogul “to invest more into moderation — particularly in countries, such as Myanmar, where Facebook has rapidly come to play a dominant role in how information is accessed and communicated.”

Long history

Zarni says the country has a “long ideological tradition by which genocides are acceptable,” which can partially be explained by support of the enemies of the then-British empire, including the Nazis, in resistance to British rule in the 1930s and 40s.

“I came from that society, I grew up with it. In the 1930s, we were quoting Hitler left and right in Burma,” he said, using the colonial-era name for the country.

“What really has emboldened the Burmese public behavior in terms of their social media interactions is the military — the military has taken up an entirely new function, it’s not only the (defense of what it sees as its) territory, but defense of culture, society, religion and race.”

Silence condemned

The country’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, has been criticized for her silence in the face of the country’s treatment of the minority.

“She will not do anything (to defend the Rohingya) — she struggled more than 15 years to get this position,” Rohingya rights defender Nay San Lwin says.

“She will never speak for any minority. If she (sympathizes with) the oppressed people, she will lose her position. She’s never been a human rights defender, she’s a politician.”

Suu Kyi and her supporters meanwhile have accused the international press of exaggerating the crisis and constructing a “huge iceberg of misinformation” which is negatively affecting her ability to run the country.

However in September 2017 she acknowledged the issue, saying her administration also wanted to “find out what the real problems were,” according to the Financial Times, and agreed to implement the recommendations of the UN-led Rakhine Advisory Commission.

____________________________________________

CNN’s Angus Watson and Bex Wright contributed to this report.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.