Solidarity Economy: Building an Economy for People & Planet

PARADIGM CHANGES, 7 May 2018

Emily Kawano | The Next System Project – TRANSCEND Media Service

1 May 2018 – We stand at the brink of disaster. The fragilities of the 2008 global economic meltdown remain, prompting warnings of another financial collapse from the likes of billionaire financier George Soros and the International Monetary Fund. Inequality in wealth and income are at historic highs, with all of the attendant dangers of concentrated wealth and power, along with the burdens that fall disproportionately on communities of color and low-income communities. Our ecosystem is in crisis. A growing number of scientists believe that humans are fueling our headlong rush toward what is being called the Sixth Extinction—the Fifth Extinction wiped out the dinosaurs.1

This is a grim picture of a long simmering crisis that is systemic in nature and created by our own hands. And yet, crisis is opportunity. The last two major economic crises, the Great Depression and the stagflation of the late 1970s, resulted in profound shifts in the dominant capitalist economic model. The Great Recession has shaken the faith in neoliberal capitalism and created an openness to thinking about new models. It will take a fundamental transformation of our system to draw us back from the brink. The solidarity economy offers pathways toward a transformation of our economy into one that serves people and planet, not blind growth and private profits.

The solidarity economy is a global movement to build a just and sustainable economy. It is not a blueprint theorized by academics in ivory towers. Rather, it is an ecosystem of practices that already exist—some old, some new, some still emergent—that are aligned with solidarity economy values. There is already a huge foundation upon which to build. The solidarity economy seeks to make visible and connect these siloed practices in order to build an alternative economic system, broadly defined, for people and the planet.

Defining the solidarity economy can be challenging. Definitions vary across place, time, politics, and happenstance, though there is increasingly a broad common understanding. This paper draws heavily on two perspectives. The first is the Intercontinental Network for the Promotion of the Social Solidarity Economy (RIPESS), which was formed in 1997 and connects national and regional solidarity economy networks that exist on every continent. The author is a member of the RIPESS Board and coordinated RIPESS’s global consultation to develop a stronger common understanding of the concepts, definitions, and framework of the solidarity economy. Through this process, RIPESS produced its Global Vision for a Social Solidarity Economy (2015) document. The other perspective that informs this paper is the U.S. Solidarity Economy Network (SEN), which was formed in 2007 at the US Social Forum in Atlanta. The author has served as SEN’s coordinator since its founding.

Solidarity Economy: Vision and Principles

The Solidarity Economy seeks to transform the dominant capitalist system, as well as other authoritarian, state-dominated systems, into one that puts people and the planet at its core. The solidarity economy is an evolving framework as well as a global movement comprised of practitioners, activists, scholars, and proponents.

The framework of solidarity economy is a relatively recent construct, though its component parts are both old and new. The term arose independently in the late 1980s in Latin America and Europe through academics such as Luis Razeto (1998) in Chile and Jean Louis Laville (2007) in France.2 The articulation of the solidarity economy was, in many ways, theory in pursuit of practice, rather than practice in conformity to a model. Scholars drew on their research and experiences to theorize and systematize a wide array of existing practices that form the foundation of “another world,” or more accurately, in the words of the Zapatista, “a world in which many worlds fit.”

We understand transformation to include our economic as well as social and political systems, all of which are inextricably intertwined. The economy is a social construction, not a natural phenomenon, and is shaped by the interplay with other dynamics in culture, politics, history, the ecosystem, and technology. Solidarity economy requires a shift in our economic paradigm from one that prioritizes profit and growth to one that prioritizes living in harmony with each other and nature.

Examples of the solidarity economy exist in all sectors of the economy, as depicted in Diagram 1. We understand the solidarity economy—and all economies—as being embedded in the natural and social ecosystems. Governance, through policies and institutions, shapes the economic system on a macro-level (e.g., national or international) as well as the micro-level (enterprise or community). Given that the solidarity economy is about systemic transformation, we are talking about change in all sectors of the economy including governance, or the state. As Argentinian economist Jose Luis Corragio put it,

When today we propose a State as a protagonist of a revolution and promoter of another economy and another territorialization, it must be on the assumption that the State itself has changed its political context, that it “governs by obeying”, following the Zapatista slogan.3

Principles

The principles of the solidarity economy vary in their articulation from place to place but share a common ethos of prioritizing the welfare of people and planet over profits and blind growth. The U.S. Solidarity Economy Network uses these five principles:

- solidarity, cooperation, mutualism

- equity in all dimensions (e.g., race, ethnicity, nationality, class, and gender, etc.)

- participatory democracy

- sustainability

- pluralism

It is important to take these principles together. Individually, they are insufficient to undergird a just and sustainable system. It is entirely possible to have alignment in one dimension but not in others. For example, it is possible to have equity without sustainability, democracy without equity, sustainability without solidarity, and so forth. Like any healthy ecosystem, the solidarity economy flourishes with a full spectrum of interconnected principles.

These broad principles can each be unpacked to articulate a more fine-grained expression of values.

Pluralism

Solidarity economy is respectful of variations in interpretation and practice based on local history, culture, and socio-economic conditions. Pluralism means that the solidarity economy is not a fixed blueprint, but rather acknowledges that there are multiple paths to the same goal of a just and sustainable world. Thus, there are national and local variations in the definition of the solidarity economy as well as strategies to build it. That said, there is a strong common foundation, as articulated in RIPESS’s Global Vision document. It draws on the experience and analysis of grassroots networks of practitioners, activists, scholars, and proponents on every continent (save Antarctica).4

Diagram 1: Solidarity Economy Prezi – An evolving presentation created by the Center for Popular Economics. Last updated 3/29/16:

https://prezi.com/y7zbactvkoxx/se-w-movement/

Solidarity

Solidarity economy is grounded in collective practices that express the principle of solidarity, which we use as shorthand for a range of social interactions, including: cooperation, mutualism, sharing, reciprocity, altruism, love, caring, and gifting. The solidarity economy seeks to nurture these values, as opposed to individualistic, competitive values and the divisiveness of racism, classism, and sexism that characterize capitalism. The solidarity economy takes forms that are old and new, formal and informal, monetized and non-monetized, mainstream and alternative, and most importantly, exist in all sectors of the economy. Of particular note is the recognition of non-monetized activities that are often motivated by solidarity, such as care labor and community nurturing (cooking, cleaning, child-rearing, eldercare, community events, helping a neighbor, and volunteer work) as not only part of the “real” economy, but the bedrock of reproduction and essential to participation in paid work. Unpaid household production accounts for an estimated $11 trillion worth of global economic activity, ranging from 18 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the US to 42 percent and 43 percent of the GDP in Australia and Portugal respectively.5 The solidarity economy not only recognizes the critical role of non-monetized transactions in enabling societies to function, but also seeks to support them through policies and institutions.

Equity

The solidarity economy framework emerged from real-world practices, many of which were undertaken by communities on the front lines of struggle against neoliberalism and corporate globalization.6 For example, in Latin America, the poor, unemployed, landless, and marginalized used solidarity economy practices to collectively build their own livelihoods in the devastating wake of the debt crisis, neoliberal policies, structural adjustment, and austerity. Examples include land takeovers by Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), factory take-overs in Argentina, the autonomista movements in Chiapas, Mexico, and the Popular Economic Organizations in Chile.7

The principle of equity is thus embedded in the solidarity economy through its historical development as well as through deliberate commitment. The solidarity economy opposes all forms of oppression: imperialism and colonization; racial, ethnic, religious, LGBTQ, and cultural discrimination; and patriarchy. Solidarity economy values are informed by the struggles of social movements. As a movement, the solidarity economy is interwoven with social movements focusing on anti-racism, feminism, anti-imperialism, labor, poor people, the environment, and democracy. We believe that we need to both resist and build; whereas social movements tend to focus more on resisting, the solidarity economy tends to focus more on building. Both are necessary and interdependent and we aim to foster stronger integration between them.

In the US, we need to be deliberate in our efforts to support and strengthen the solidarity economy in marginalized and oppressed communities and to be mindful of the danger of becoming isolated in relatively affluent and white communities. In order for the solidarity economy to uphold equity, it must be part of the solution to poverty and oppression for low-income communities, communities of color, and immigrant, LGBTQ, and other marginalized groups.

This is not to imply that solidarity economy practices are absent in low-income communities. Throughout time, marginalized communities have practiced informal forms of community self-provisioning, gardening, child and elder care, mutual aid, lending, and healing. Many of these practices are invisible because of their informal nature—they are not incorporated, they do not pay taxes, they do not hang out a shingle, they are not listed in a directory. In terms of formal sector solidarity economy practices, historically, there have been ebbs and flows in marginalized communities. For example, Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s recent book Collective Courage documents a history of thriving cooperatives in the African American community.8 Sadly, these businesses came under racist attack and strangulation, resulting in the loss of this history until Gordon Nembhard uncovered it. In the last section of this paper on real world examples, solidarity economy practices in marginalized communities are highlighted.

Participatory Democracy

The solidarity economy embraces participatory democracy as a way for people to participate in their own collective development. Making decision-making and action as local as possible, sometimes referred to as subsidiarization, helps people participate in decision-making about their communities and workplaces and in the implementation of solutions.

The principle of democracy extends to various aspects of life, including the workplace. The solidarity economy upholds self-management and collective ownership. The RIPESS Global Vision document states:

Self-management and collective ownership in the workplace and in the community [are] central to the solidarity economy…There are many different expressions of self-management and collective ownership including: cooperatives (worker, producer, consumer, credit unions, housing, etc.), collective social enterprises, and participatory governance of the commons (for example, community management of water, fisheries, or forests).9

Therefore, capitalist enterprises, in which there is an owning class and a working class, are not included in the solidarity economy even if the company is socially responsible and operates according to a triple bottom line (social, ecological, and financial). This is because the owner ultimately has control over the enterprise and profits. The existence of worker participation in decision-making granted by management or negotiated by a union does not constitute workplace democracy insofar as it can be taken away or lost. In contrast, a cooperative structure by definition gives workers decision-making power, even if there are instances where this is poorly enacted. While the solidarity economy does not extend to capitalist enterprises, in practical terms, there are many allies and much common ground to be found among socially responsible capitalist enterprises. The long-term vision of the solidarity economy remains committed to economic democracy, but transitional process will need to build alliances while working to move allies in the direction of solidarity economy principles.

Sustainability

RIPESS has embraced the concept of buen vivir or sumak qawsay (living well), which draws heavily upon Andean indigenous perspectives of living in harmony with nature and with each other. The Ecuadoran National Plan for Good Living defines it as: “Covering needs, achieving a dignified quality of life and death; loving and being loved; the healthy flourishing of all individuals in peace and harmony with nature; and achieving an indefinite reproduction perpetuation of human cultures.”10

An important component of buen vivir is the rights of Mother Earth or Nature. The solidarity economy upholds the principle of sustainability and RIPESS has embraced the more radical notion that ecosystems have the legal right “to exist, flourish and regenerate their natural capacities.”11 Nature cannot be seen as something that is only for humans to own and exploit. The rights of Mother Earth (nature) have been enshrined in the Constitutions of Bolivia and Ecuador and have been recognized by more than three dozen communities in the US, including Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and San Bernadino, California.

Throughout the world there are practices that are well aligned with these values and others that are partially aligned. In other words, there is a spectrum of alignment. Those that are partially aligned but conflict in a fundamental aspect, include, for example, capitalist social enterprises and social investment. We see these as potential strategic allies, while also remaining vigilant of the danger of cooptation. The solidarity economy movement works to break down the silos that separate various SE practices and also to encourage allies to move toward full alignment with all of the SE values.

A New Narrative

While conventional economics likes to portray itself as a science, the economy is in fact a social construction, not a natural phenomenon like gravity or solar radiation. The mainstream economics of capitalism is built on a story or narrative. The central character of this narrative, homo economicus or economic man, is the basis from which economic theory, models, and policies are spun. Our real world economy builds upon particular assumptions about homo economicus, namely that he is rational, calculating, self-interested, and competitive. He is motivated by self-serving individualism rather than by a concern for the well-being of the community, the common good, or the environment.

There is ample research that demonstrates that human nature is complex, comprised both of self-serving and solidaristic tendencies. The limitations of homo economicus have by now been well demonstrated in numerous fields including economics, anthropology, and biology.12

Economists, of course, know that homo economicus is an unbalanced and unrealistic depiction of human beings. However, mainstream economics continues to star homo economicus because it is a useful simplification for mathematical modeling, because it justifies laissez faire neoliberalism, and because economics and behavior in the magic marketplace can be treated in isolation of emotion, culture, and social norms that are the province of the soft sciences—sociology, anthropology, and psychology.

The logic of such one-sided assumptions about human nature and behavior have real world consequences. Capitalism is grounded in the belief that individuals acting in their own self-interest will, through the power of the invisible hand and market, generate optimal and stable economic outcomes. As Adam Smith famously wrote:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages.13

Conservatives from author Ayn Rand to the Chicago School’s Milton Friedman championed the virtues of selfishness as the basis of society and economy. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher forged this belief system into corporate-dominated neoliberalism, which is today severely wounded but still dominant.

Conversely in this economic story, collective action, from cooperatives to community commons are predestined to fail due to the rational, self-interested behavior of homo economicus.

For example, Garrett Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons, first published in 1968, argued that open access to communal resources such as pastureland leads to disastrous overgrazing.14 Arguing that even after the maximum number of animals that the land can support is reached, each individual still has incentive to add to his herd, as his gain is 100 percent of the value of the animal while his loss is only a fraction of the degradation due to overgrazing. Thus, what is rational for the individual is irrational for the group. The answer then is to remove collective access in favor of privatization or enclosure by an individual owner or the government. In other words, according to Hardin, we have an economic system that is predisposed to discourage collective ownership, control, and management.

In 2009, Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel Prize in Economics for her work documenting the many examples of forests, irrigation systems, fishing grounds, and pastureland that have been managed as commons by their stakeholders more efficiently, sustainably, and equitably than by the state or private owners.15 She draws not only on her own research, but also on a well-established body of empirical and game theory work that demonstrates that, contrary to predictions that people will behave as self-serving “rational egoists,” there is an impulse toward action that benefits the collective and that can be reinforced and sustained through a well-defined set of design principles.

As the critiques of homo economicus continue to mount, he is increasingly endangered as the central character in our story of the economy. The new emergent protagonist, who we venture to call homo solidaricus, is more complex—both self-interested and solidaristic—and more diverse, as human behavior is understood to be shaped by a range of social and natural forces, suggesting therefore that there is no singular, universal human nature. This understanding of human behavior provides a strong foundation for building a solidarity economy that draws on the better angels of our nature—solidarity, cooperation, care, reciprocity, mutualism, altruism, compassion, and love. At the same time, it is critical that solidarity economy practices do not succumb to the naïve and unbalanced belief that humans are only solidaristic. As Ostrom shows, cooperative, collective systems must be designed to account for self-interested impulses or they will not be resilient.

A Metaphor for Change

As detailed below, there is already a rich foundation of practice to build upon; however, the solidarity economy and its component parts remain, for the most part, invisible. Part of the explanation lies in the fact that the various practices— worker cooperatives, credit unions, social currencies, and community land trusts, etc.—operate in their own silos. They are seen and indeed tend to develop in an atomized fashion rather than as connected pieces of a whole system.

An apt metaphor for thinking about the social and economic transformation that the solidarity economy seeks is the metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly. When the caterpillar spins its chrysalis, its body begins to dissolve into a nutrient rich soup. Within this soup are imaginal cells that the caterpillar is born with.16 These cells have a different vision of what the caterpillar could be and in fact are so different from the original cells that the residual immune system seeks to attack and kill them.17 Still, the surviving imaginal cells begin to find each other and, recognizing each other as part of the same project of metamorphosis, connect to form clusters. Eventually these clusters of imaginal cells start to work together, integrate with each other, take on different functions, and build a whole new creature. As the imaginal cells specialize into a wing, an eye, a leg, etc., they integrate to create a whole new organism that emerges from the chrysalis as the butterfly.

In the same way, we can think of the many real-world “solidaristic” economic practices as imaginal cells, operating in isolation from one another and existing in a hostile, or at best indifferent, environment. The solidarity economy as a movement works to help these imaginal cells recognize one another as part of the same project of economic metamorphosis and to pull together to build a coherent economic system with all the “organs” that are necessary to survive in finance, production, distribution, investment, consumption, and the state.

Drivers of Change: The Need to Proliferate & Integrate

While the caterpillar may be born with imaginal cells, all economic practices, whether capitalist or solidarity economy, do not simply exist in nature because they are social constructions. Thus, the task is to both proliferate and to connect or integrate these practices.

What drives the proliferation of solidarity economy practices? We look at three dimensions that drive the expansion of the solidarity economy: social and economic drivers, the ecological crisis, and the state.

Social and Economic Factors

Ideology

There are many examples in which people engage in the solidarity economy not out of need but because of an ideological, and sometimes spiritual, commitment. For example, many people choose to become members of food and worker cooperatives, community-supported agriculture programs, credit unions, and engage in community volunteer work not because they lack other options but because doing so expresses their values. In other cases, practical motivation is reinforced by ideological motivations.

We can think of the many ‘solidaristic’ economic practices as imaginal cells, operating in isolation from one another and existing in a hostile environment.

Practical need and hard times

Solidarity economy practices have often been motivated by hard times or simply the challenge of survival. Over the past thirty-five years, solidarity economy practices have surged in response to the long-term crises of neoliberalism, globalization, and technological change. These trends have generated punishing levels of political and economic inequality and created long-term un- and under-employment, acute economic insecurity, and reductions in government social programs and protections. The wealthy elite are able to use their wealth and influence to skew political priorities toward corporate profits and away from social and environmental welfare.

Many scholars talk of the “end of work” as people are replaced by machines.18 Some envision a future of abundance and leisure, while others see a dystopia in which the jobless cannot earn enough to meet their basic needs. Currently, the latter vision is steadily encroaching. Since 2000, the share of people engaged in work has been trending downward, particularly among men of prime working age (twenty-five to fifty-four years old).

In this context, many people and communities have become tired of making demands on a deaf or under-funded government. Moved by a combination of desperation, need, practicality, and vision, people have turned their energy to building their own collective solutions to create jobs, food, housing, healthcare, services, loans, and money. These practices operate both inside and outside of the formal and paid economy.

Economic Crisis

While neoliberalism, globalization, and automation have created a long-term crisis, the economic crisis of 2008 was sharp and shattering. It shook the confidence of the world in the neoliberal model of capitalism and provided a rare opportunity to push for fundamental change. Historically, crises have led to fundamental shifts in the dominant economic paradigm. The Great Depression set the stage for the overthrow of the neoclassical orthodoxy, which held that markets would right themselves and that the government should do nothing. It ushered in Keynesianism, which argued that the government must jump start and stabilize the economy as well as promote social welfare. The crisis of stagnation (simultaneous inflation and high unemployment) of the late 1970s led to the overthrow of Keynesianism by neoliberalism or, as it was called at the time, Reaganomics or Thatcherism.

The 2008 economic crisis has shaken confidence in neoliberalism to its core. The window of opportunity provided by the crisis is not closed. The systemic fractures, particularly in the financial system, still exist and the continuing economic tremors suggest that another financial collapse may not be far off. The long-term trend of growing inequality, un-and under-employment, stagnant wages, and precarious labor continues to fuel interest and engagement in solidarity economy practices such as cooperatives, social currencies, community supported agriculture, and participatory budgeting, to name a few. In the US, Bernie Sanders, who ran openly as a socialist candidate for President found support, even among conservatives, on issues of inequality and the excesses of the corporate and financial elite.

Ecological crisis

The other long term crisis that is driving the growth of the solidarity economy is ecological. There is a growing consensus that human activity is responsible for creating a new geological epoch called the Anthropocene (human epoch) in which humans are driving rapid changes such as global warming, rising ocean levels, intensified hurricanes and tornadoes, ocean acidification, and the loss of biodiversity.19

There is a substantial amount of evidence that these changes are causing a rapid escalation of species extinction and, as mentioned in the introduction, that we may be heading toward the Sixth Extinction—a global mass extinction, the likes of which has only been seen five times before in the history of the Earth.20 The Fifth Extinction saw the end of the dinosaurs.

The solidarity economy is sympathetic to the view that the capitalist system is inherently ecologically unsustainable. This is not because capitalists are evil or stupid, but because the fundamental logic of capitalism requires each individual business to maximize profits and grow, or else be competed out of business. As demonstrated in the prisoner’s dilemma, a classic scenario used in game theory, what is rational for the individual is irrational and decidedly sub-optimal for the whole.21 Continual growth requires ever-increasing levels of consumption both on the supply and the demand side, which is unsustainable given the finite resources of the Earth.

RIPESS’s position on growth is that its value depends on how it is defined:

SSE questions the assumption that economic growth is always good and states that it depends on the type and goals of the growth. For SSE, the concept of development is more useful than growth. For example, human beings stop growing when they hit adulthood, but never stop developing.22

Solidarity economy responses to these drastic ecological changes cover a diverse range such as emphasizing local production for local consumption, integrating ecological principles into production and agriculture (e.g., permaculture and eco-industry), turning waste into inputs, restoring healthy ecosystems, reducing the carbon footprint, shared consumption (e.g., tool and toy libraries), mutual aid disaster relief, and community owned energy generation.

As mentioned above, the solidarity economy embraces a deeper change as well— that of recognizing the rights of Mother Earth and giving it standing. Nature does not exist simply for humans to exploit for our own ends. Human activity must respect the rights of ecosystems to exist. In the US, not only have the rights of Nature been recognized in three dozen communities, but they has also been used to fight destructive practices such as fracking that would imperil an ecosystem’s ability to flourish:

In the United States, in November 2014, CELDF (Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund) filed the first motion to intervene in a lawsuit by an ecosystem. The ecosystem—the Little Mahoning Watershed in Grant Township, Indiana County, Pennsylvania—sought to defend its own legal rights to exist and flourish. The rights of nature were secured in law by Grant Township in June 2014… (thereby) banning frack wastewater injection wells as a violation of those rights.23

The rights of Mother Earth is important not only as a practical tool to combat ecosystem destruction, it is also part of the worldview of buen vivir—or “living well,” in harmony with each other and Mother Earth, that we as human beings must attune to. These sorts of shifts in worldview are part of the impetus behind the growth in the solidarity economy.

Government

Given that the solidarity economy is a big tent, there are those who embrace this framework from an autonomista or anarchist perspective and eschew working with the state. On the other hand, there are many others in the solidarity economy movement who work to transform the state, its institutions, and its policies. There are many paths to the common goals of a more just, equitable, democratic, and sustainable world and we should not fall victim to fighting each other over the single, “right” way forward.

Governments, at the local, national, and international levels, are engaged in fostering the solidarity economy, or its components, both directly through the public sector as well as through supportive policies such as legal recognition of collective and mutual practices, and tax, investment, and procurement policies. There are a growing number of examples. On a municipal level, New York City and Madison, Wisconsin have allocated millions of dollar to support the development of worker-owned cooperatives with an emphasis on job and wealth creation for low-income and marginalized communities. A growing number of countries, including France, Spain, Portugal, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, and the Québec province in Canada have passed, or are in the process of developing, framework legislation that provides recognition and support for the solidarity economy.24 Brazil, France, and Luxemburg have ministries of solidarity economy and Bolivia and Ecuador have enshrined solidarity economy in their constitutions.

Very often government support for the solidarity economy is the result of pressure from social movements. It is far too rare that governments at any level take the lead in promoting policies that support equity, economic democracy, sustainability, and collective action without public pressure. As discussed below, social movements and solidarity economy practitioners are two sides of the same coin: resist and build; oppose and propose. Both are necessary to push through supportive policies, and just as importantly, to transform the state itself.

It is worth noting that some of these government initiatives seek to support the social economy, not necessarily the solidarity economy. It is worth a brief digression on the difference between these two concepts.25 The European Union’s Charter Principles of the Social Economy identifies four families of social economy organization: cooperatives, mutuals, associations, and foundations, which adhere to principles of democratic control by membership, solidarity, primacy of social and member interests over capital, and sustainability.26 The social economy aligns with solidarity economy principles and is embraced as an important component. The social economy, however, does not necessarily seek systemic transformation, whereas the solidarity economy does. The social economy accommodates a range of positions regarding the capitalist system, from regarding itself as a legitimate pillar of capitalism with a particular strength in addressing social and economic inequalities, to being in full support of a transformative, post-capitalist agenda.27 Thus, when governments pass social economy laws, they are supporting a particular sector of the solidarity economy but not necessarily the goal of systemic transformation.

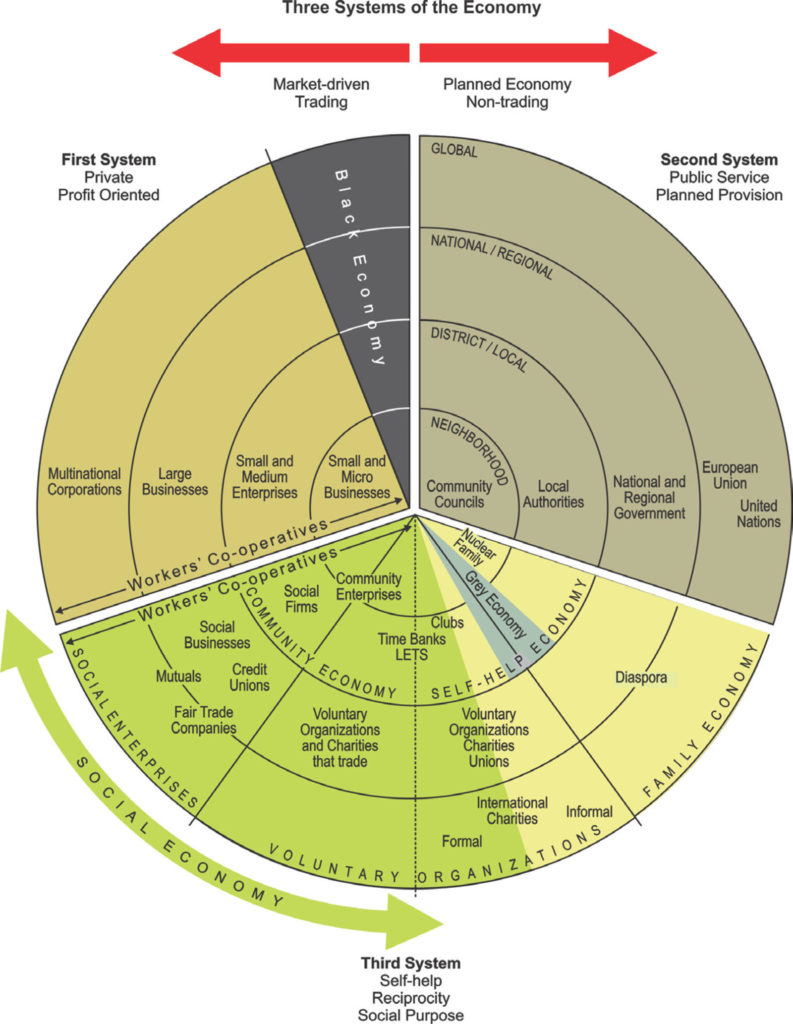

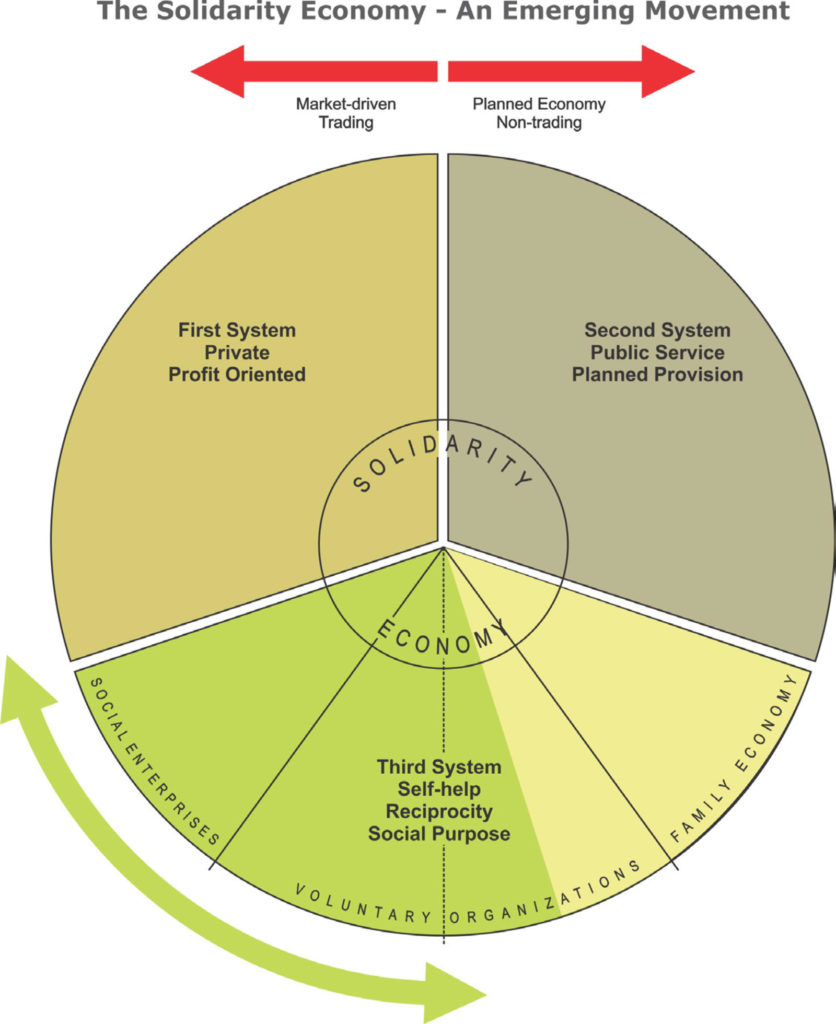

One final noteworthy distinction is that the social economy is far narrower than the solidarity economy, which, for example, includes the state (assuming fundamental change) and non-monetized transactions such as care and volunteer labor. Diagram 2 depicts the social economy as a major part of the third system of self-help, reciprocity, and social purpose. Diagram 3 illustrates the solidarity economy as occupying space, albeit not a dominant one, across all three sectors: public, private and the third sector.

Diagram 2 and 3 from : Michael Lewis and Pat Conaty, The Resilience Imperative: Cooperative Transitions to a Steady-State Economy (Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers, 2012).

Integrating Solidarity Economy Practices

Having looked at what drives the proliferation of solidarity economy practices, we now turn to the question of how to integrate them into an interconnected system, one like the caterpillar’s, in which the imaginal cells come together, specialize, and emerge as a whole new organism. This process relies on three foundations: public awareness, developing solidarity economy value chains, and capacity building.

Public awareness is a first step in the process of the solidarity economy’s imaginal cells coming to recognize each other as part of the same project of transformation. While every single individual practice does not need to embrace this view and agenda, it is important to build common cause among a substantial portion of practices. This is a challenge of outreach, communication, and education. Solidarity economy networks throughout the world are engaged in this work in a variety of ways.

Creating solidarity economy value chains is a strategy of “building our own economy” in which solidarity economy enterprises source from other solidarity economy producers.28 For example, the Brazilian cooperative Justa Trama [Fair Chain] works with a number of cooperatives to produce bags and t-shirts. It sources cloth from Cooperativa Fio Nobre, which buys its raw organic cotton from Coopertextil. Justa Trama buys buttons made out of seeds and shells from Coop Acai. The final production of the bags and t-shirts is done by two sewing cooperatives, Univens and Coopstilus, in Porto Alegre and Sao Paulo. Members involved in this solidarity economy supply chain have benefitted from the collaboration through aspects such as increased sales, landing long term contracts, and allocation of profits to those with the most need.29

This is an example of a social economy supply chain of producers and suppliers. To make it a value chain, the supply chain would be integrated with solidarity economy channels for finance, distribution and exchange, and consumption. For example, the businesses might be financed by a community bank, distributed through a fair trade network, paid for with social currency, and sold through a community cooperative store.

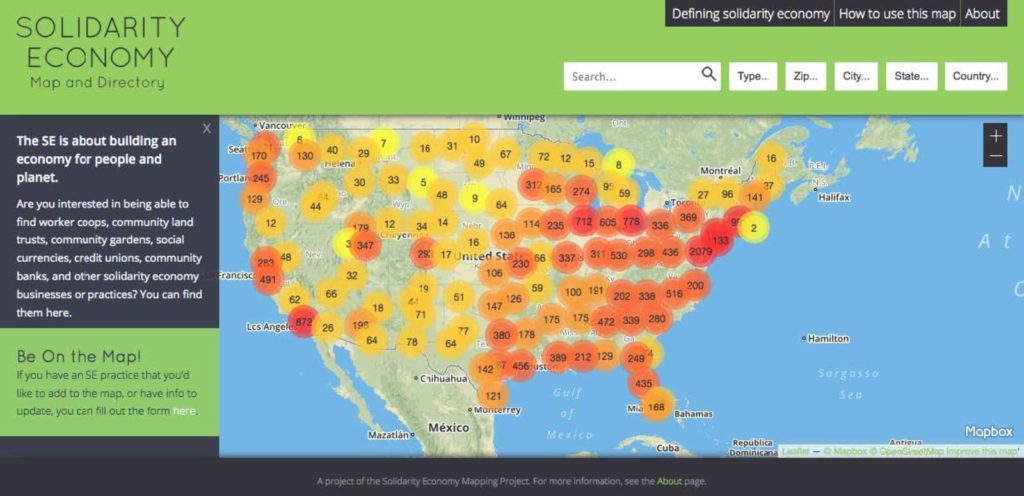

In order to build such solidarity economy value chains, there is a need for capacity building. Some solidarity economy producers do not know of solidarity economy suppliers or they do not exist. The US Solidarity Economy Map seeks to address the first problem by making it easy for SE producers and suppliers to find each other.30

The second problem requires the development of a more diverse ecosystem of solidarity economy producers, particularly in manufacturing. There is a welcome upsurge in cities that are investing in cooperatives as a strategy of inclusive economic development. New York City and Madison, Wisconsin allocated over $3 million and $5 million dollars respectively for worker cooperative development aimed at low-income communities and communities of color.31 Many other cities such as Richmond, California; Jackson, Mississippi; and Cleveland and Cincinnati, Ohio have city, labor, and/or grassroots initiatives to support the development of worker cooperatives.

Resist and Build

Advocates of the solidarity economy are engaged in building, strengthening, and connecting actual practices—our imaginal cells—in order to show that they are viable, in order to advocate for a supportive environment, in order to create a critical mass for systemic transformation, and to build the road by walking. We also believe that it is equally necessary to resist the exploitation, injustice, oppression, and destructiveness of our social and economic system. To resist and build; to oppose and propose—these are both a necessary and two sides of the same coin.

In the US, social movements have tended to favor resistance over building, though that is beginning to change. The solidarity economy is the other half of this coin. For example, advocates of the solidarity economy support improving wages and working conditions but also promote workplaces that are owned and managed by the workers. Solidarity economy supports re-distributional policies but works to build a system that does not generate such inequality in the first place. For example, community land trusts and other “mited equity” cooperative housing models take real estate out of the speculative market.

To resist and build; to oppose and propose—these are both a necessary and two sides of the same coin.

The solidarity economy is about people collectively finding ways to provide for themselves and their communities. It is not primarily about the government doing it for them. It is about the government being a partner in creating the structures and supports for people to create their own solutions—to create jobs and livelihoods, to grow food, manage their local ecosystem, allocate spending, and so forth. Rather than a redistributive welfare state, the goal is to create a system in which everyone has enough to live well.

Building a Movement: RIPESS: a Network of Networks

The solidarity economy continues to grow and gain traction as a global movement for economic transformation. The Intercontinental Network for the Promotion of the Social Solidarity Economy (RIPESS) connects all the continental networks, which are in turn comprised of regional and national solidarity economy networks. RIPESS-North America is comprised of three networks representing the US (U.S. Solidarity Economy), Canada (Canadian CED Network), and Quebec (Chantier de l’économie sociale). Other continental networks are more complicated than North America, having many more states, languages, and member networks, some of which are organized on the basis of geography, and others by sector.

RIPESS was formed in 1997 at a meeting on the globalization of solidarity in Lima, Peru. Subsequent international Social Solidarity Economy meetings have been held every four years: in Quebec (2001), Dakar (2005), Luxemburg (2009), and Manila (2013).32 Affiliated projects include the ongoing development of a Global Vision of Social Solidarity Economy, Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) Global Mapping, web portals such as RELIESS (policy) and Socioeco (all things solidarity economy), a LinkedIn SSE discussion group, and working groups on education, communication, and networking.

International organizations are starting to integrate SSE into their agendas. SSE has long been part of World Social Forums, including the 2013 World Social Forum of Solidarity Economy held in Brazil. The International Labour Organization (ILO) organizes an annual Social Solidarity Economy Academy; in 2013, the UN Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) held a conference in Geneva on the social solidarity economy, and subsequently the UN Inter-agency Taskforce on the Social Solidarity Economy was established which has helped to support SSE representation in regional consultations on the UN’s post-2015 Sustainable Development agenda in Asia, Latin America, Europe, and North America.

Real-world examples

The solidarity economy rests upon a huge foundation of existing practices. It does not need to be built from scratch, but rather, requires that its imaginal cells recognize on another as part of a common process of metamorphosis.

Solidarity economy, in its commitment to pluralism, does not advocate a one-size-fits-all model—different approaches are appropriate depending on historical, cultural, and political realities. The unifying core of principles leaves room for a great deal of diversity as well as debate. That being said, solidarity economy is strongly committed to collective ownership and management. Thus, cooperatives are a backbone of the solidarity economy. Even in regions such as Eastern Europe, and in some African countries, where cooperatives have a bad name because of a negative association with authoritarian forced collectivization or corrupt forms, there are often functional equivalents to cooperatives but with a different name.

The solidarity economy exists in every economic sector: production, distribution and exchange, consumption, finance, and governance. Table 1 provides examples of solidarity economy practices in each sector, though this is far from exhaustive. In general, firms referenced in these examples are collectively and democratically owned and run for the benefit of their members or the community. The solidarity economy does not preclude turning a profit (or surplus), nor engaging in market exchange, but it does not regard markets or profit as ends in themselves.

While this typology may seem straightforward, upon deeper exploration we find that defining the boundaries of the solidarity economy is more complicated.

Many of these practices straddle different sectors and it is impossible to construct a “perfect” taxonomy without some overlap. For example, community supported agriculture is both production and a collective form of distribution and exchange. Additionally, some community gardens straddle production and distribution through gifting surplus.

The Solidarity Economy Mapping Project used the following two criteria to decide which practices to include in its map of the solidarity economy.

- The practice is in substantial alignment with solidarity economy principles (equity, sustainability, solidarity, democracy, and pluralism).

- There is nothing inherent in the structure of the practice that violates solidarity economy principles.

Take worker cooperatives for example.The seven cooperative principles that most cooperatives subscribe to coincide with all five of the solidarity economy principles and there is nothing inherent in the worker cooperative form that violates any of the principles.33 We consequently include worker cooperatives as a type of solidarity economy practice. There may well be worker cooperatives that operate in ways that are not aligned with these principles—for example, they engage in sexist, racist, or homophobic practices. Such a cooperative would be excluded for this reason. However, there is nothing about worker cooperatives in general that gives cause to categorically exclude them.

Table 1 – Typology of Solidarity Economy Practices

|

Production |

Distribution & Exchange |

Consumption |

Finance |

Governance |

| Worker cooperatives

Producer cooperatives Volunteer collectives Community gardens Collectives of self-employed Unpaid care work |

Fair trade networks

Community supported agriculture and fisheries Complementary/ Social/ Local currencies Time banks Barter or Free-cycle networks |

Consumer cooperatives Buying Clubs

Cooperative housing, Co-housing, intentional communities Community land trusts Cooperative sharing platforms |

Credit unions

Community development credit unions Public banking Peer lending Mutual association (eg. insurance) Crowd-funding |

Participatory budgeting

Commons/ community management of resources Public sector (schools, infrastructure, retirement funds, etc) |

Some practices are strongly aligned with one dimension but not necessarily with others. Take for example, social enterprises. Given that they have a social mission, they are likely to be aligned with principles of equity, sustainability, and solidarity. Capitalist social enterprises that have owners or stockholders who are in control while workers lack decision-making power, do not align with the democratic principle of the solidarity economy. Even if the owner allows workers to have input into decision-making, this privilege can just as easily be withdrawn by the owner. Because of the structural conflict with democratic principles, they are excluded from the solidarity economy typology, although they may be valuable allies.

However, a subset of social enterprises that are collectively and democratically owned and managed are included in the solidarity economy. For example, a business that is run by a non-profit or is worker, multi-stakeholder or community-owned would fall in this category. In fact, in some parts of the world, a social enterprise is defined as one which is collectively and democratically owned and managed. In the US, a social enterprise is generally defined as a business with a social aim, so includes capitalist as well as collectively owned social enterprises.

Unpaid care work, as feminists have long argued, should be recognized as an economic activity that enables the reproduction of society, and therefore has economic value deserving of support. We realize that there are far too many instances and cultures where care labor is performed under very oppressive and exploitative conditions that patriarchal culture enables. We would not embrace this kind of care work as an example of the solidarity economy, but in including unpaid care work in our taxonomy, we seek to affirm its economic and social value even though it is non-monetized.

Let’s take one more example. Fair trade seeks to give growers a fair price, which seems like an obviously good thing. However, when a giant transnational corporation like Wal-Mart comes out with its own brand of fair trade coffee while simultaneously union busting, paying poverty wages, and pressuring price reductions for other non-fair trade goods, it is hardly cause to include Wal-Mart in the solidarity economy, even as an ally. Furthermore, some fair trade organizations have chosen to certify large plantations that pay their workers only minimum wage and give them virtually no decision-making power rather than supporting grower cooperatives of small farmers. Some fair trade distributors are collectively owned and managed, such as Equal Exchange and non-profit fair trade organizations like 10,000 Villages, and squarely aligned with solidarity economy principles.

In summary, the boundaries of the solidarity economy are complicated and sometimes require further information about individual enterprises. It is nonetheless useful to identify models that, on the whole, tend to be aligned with solidarity economy principles. Below are a couple of examples in each sector, including ones in low-income communities and communities of color.

Production

Worker Cooperatives: These are businesses that are owned and democratically run by their workers on the basis of one worker one vote. As owners, the workers get to decide how to use profits—how much to reinvest, save, and/or share out among the workers. On the whole, worker cooperatives are more resilient, more equitable, and prioritize the welfare of workers than conventional capitalist businesses. Studies of worker cooperatives in Québec and Canada found that the five-year survival rate was around 60 percent for cooperatives compared to 40 percent for conventional businesses.34 Worker cooperatives tend to have a low ratio of highest to lowest paid—in the neighborhood of 4:1—compared to a US average of 295:1.35 Pay is generally comparable or better in worker cooperatives, and job security is better. In tough times, worker owners tend to take a pay cut rather than lay off workers.

Source: Democracy at Work Institute webpage: http://institute.coop/sites/default/files/State_of_the_sector.pdf

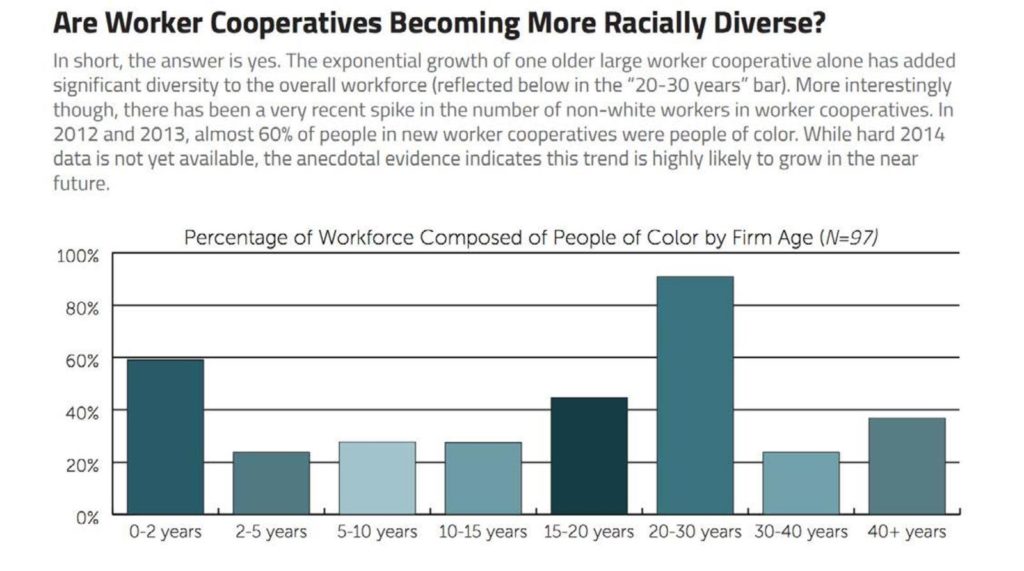

Since the Great Recession of 2008, there has been an upsurge in worker-cooperative start-ups and cities are beginning to invest in worker cooperatives as a strategy for inclusive economic development in low-income communities and communities of color.36 As previously noted, New York City and Madison have allocated millions of dollars for worker-cooperative development and numerous other cities are investing in other ways. Labor unions are supporting worker cooperative development as a strategy of creating good jobs and businesses controlled by the workers.

In 2009, the United Steelworkers announced a collaboration with Mondragon, the most famous cooperative network in the world, focused on developing union cooperatives in the US such as WorX Printing in Worcester, Massachusetts. The Cincinnati Union Co-op Initiative (CUCI) is developing a worker-owned farm, food hub, and grocery store, and exploring a number of other potential businesses.

Self-provisioning, Urban Homesteading, Community Production, and DIY: As mentioned in the values section above, the solidarity economy views non-monetized and non-market exchanges as an important component of the “real” economy. For example, unpaid care work such as child-rearing, elder care, cooking, house-keeping, or community volunteer work is essential for the reproduction of human societies. Throughout the world, women continue to shoulder far more of this unpaid care work than men and often this is on top of paid work. A number of countries now track unpaid care labor through time-use surveys. Recognizing and measuring unpaid labor as part of the “real” economy provides leverage for promoting gender equity.

There is also a fast-growing culture of self-provisioning, spurred on by a desire to live more sustainably, as well as a growing sense of economic precariousness amplified by the Great Recession.37 This renewed interest in self-sufficiency is driving thousands of people to build their own homes; generate their own power; grow their own food; capture rainwater; raise chickens and bees; organize skill shares, swaps, and barn-raisings; and exchange goods and services using social currencies or time banking. Frithjof Bergmann’s thinking about New Work, which looks beyond jobs and toward provisioning on a community scale, has found resonance in cities such as Detroit, where job bases have disappeared.38 As opposed to the back to the land movement of the 1970s that sought to escape to a low-tech lifestyle in isolated homesteads and communes, this vision of community production has taken root in towns and cities and makes full use of the very technologies that are destroying so many jobs, such as digital fabrication and 3-D printers. This technology is being used to localize production of things as complex as a car,39 as large as a house,40 or as personalized as orthodontic retainers,41 enabling communities to become more self-sufficient.

Distribution & Exchange

Social Currencies and Time Banks: These operate alongside the “official” forms of money and enable the exchange of goods and services either through some form of socially created money or time credits. Local forms of money help boost the local economy by increasing the supply of money as well as by keeping it circulating in the local economy rather than “leaking” outside. Social currencies have a long history throughout the world. Some operate far beyond the local level. For example, the Swiss WIR Cooperative has been around since 1934, has 62,000 members, and issues its own money, which is used in $1.41 billion worth of transactions a year.42

In the US, Berkshares are an example of a printed local currency that operates in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts.There are currently over 400 businesses that accept Berkshares including restaurants, accommodations, auto repair shops, healthcare services, landscaping firms, and farms. People can purchase Berkshares from local banks at a 5 percent discount, which gives people an incentive to buy them. Businesses have a disincentive to cash out their Berkshares for dollars because they would lose 5 percent of the face value of their Berkshares.

Time banks are a form of electronic exchange in which people earn time credits for each hour they work. So one person could earn an hour credit by reading to an elderly person and then use that hour credit on a massage or legal services. Time banking has been used in creative ways. For instance, Dane County Timebank’s Youth Court in Madison, Wisconsin and the DC Time Dollar Youth Court Program allow young people volunteering as jurors in cases involving their peers to earn timebank hours that they can spend on things like tutoring, music, and art lessons.

There has been explosive growth throughout the world in social currencies and time banking in recent years, partly in response to the continuing economic recession and austerity programs.

Community supported agriculture (CSA): This supports local, small farmers and sustainable agricultural practices by creating dependable demand for their produce as well as up-front capital for each year’s crops. CSA members pay for a seasonal or yearly subscription, which entitles them to a share of whatever is produced each week. In good years, everyone shares in the bounty and in bad years, everyone shares the pain. CSA members have a relationship with the farm and farmer rather than buying food on the basis of impersonal market transactions. In the US, Local Harvest listed 4,571 CSAs in its directory in 2012. It estimates that this represents only 65–70 percent of those in operation, so there may be over 6,000 CSAs in the US.43

Some CSAs have found ways to serve low-income people by subsidizing shares through donations from wealthier members. Other CSAs such as Uprising Farm in Bellingham, Washington have set their share price to be affordable for people on fixed incomes and accept food stamps/EBT from low-income people.

Consumption

Community Land Trusts (CLTs): These are non-profit organizations that create permanently affordable homes by taking housing out of the speculative market. There are numerous variations, but here is one example of how it works: the CLT owns the land and leases it to the homeowner for a nominal sum. The homeowner pays for the home, not the land, which in addition to grants and other subsidies that the CLT is able to leverage, can make a home affordable. In Vermont, the homes in the Champlain Housing Trust are typically half the price of a comparable open-market properties. Owners can sell their houses at a fair rate of return, but the price of the house is capped in order to maintain permanent affordability. Homeownership is not the only option in CLTs. There are also rental units that are owned by the CLT for those who cannot afford or do not wish to own their own home.

Not only do CLT’s take housing off the speculative market, the model also allows for protection during economic and housing crises. A study conducted in December 2008 showed that foreclosure rates among members of eighty housing trusts in the US were six times lower than the national average, due to a range of supportive services and interventions provided by the CLTs.44 The success of CLTs has led to impressive growth, from 160 in 200545 to 240 in 201146 . In the wake of the disastrous boom and bust of the housing market, this is a model whose time has come.

The Sharing Economy and Platform Cooperativism: The sharing economy certainly sounds like something that is entirely in keeping with the solidarity economy. Some parts of the sharing economy, such as skill-shares, gifting, tool and toy libraries, and other forms of traditional volunteer and care work are clearly aligned with the solidarity economy. These forms of sharing build relationships and community, reduce consumption, and amplify knowledge and skills. More controversial aspects of the sharing economy are capitalist online platforms such as Uber, Lyft, and Task Rabbit, which have rightly come under heavy fire for enriching the owners on the backs of “freelance” workers who have no job security, health insurance, retirement benefits, vacation time, or workplace protection coverage. These workers in the “gig economy” are fueling the rapidly expanding number of contingent workers, who now make up approximately 40 percent of the US workforce.47

Platform Cooperativism defines a particular approach to the sharing economy that leverages many of the same technologies that enable Uber and Task Rabbit, but with a collective ownership structure and the goal of benefiting multiple stakeholders rather than simply maximizing profits.48 One example is Loconomics, a worker-owned version of Task Rabbit, where people can find and offer professional services through an online platform.49

Finance

Public banking: This is gaining a great deal of support, especially after the financial meltdown of 2008. Public banks are owned by the people through local, state, or national government. They exist to serve the public good, as opposed to maximizing profits for shareholders like private banks.

The only state bank currently in operation is the Bank of North Dakota. All of the state’s assets and revenues are held by the bank.The bank targets their lending toward the state’s priorities such as agriculture, infrastructure, economic development, and education. In the wake of the financial crisis, many states were hard hit by downgrades to their credit ratings, which made it more difficult and expensive to borrow money. North Dakota, on the other hand, sailed through the Great Recession with record high budget surpluses, relying on its state bank to provide funds that were then lent out through local banks.

Revenues from the bank are paid to its single shareholder—the people of North Dakota. In the past ten years the bank has paid over $300 million to the state’s general fund. By contrast, most other states deposit their assets and revenues in commercial Wall Street banks, which do not use those deposits for the public good but to maximize profits.

Since 2009, more than twenty states as well as numerous cities like Santa Fe, in New Mexico, have filed legislation to start or explore the feasibility of a public bank.

Credit union membership

Credit unions: These are financial institutions that are non-profit cooperatives, owned and controlled by their members/depositors. Most credit unions make personal loans, but some lend to small businesses and start-ups. Community Development Credit Unions serve predominantly low-income communities and play a critical role in providing an alternative to predatory lending by offering fairly priced loans, non-exploitative pay-day loans, and sound financial counseling and financial literacy education.50

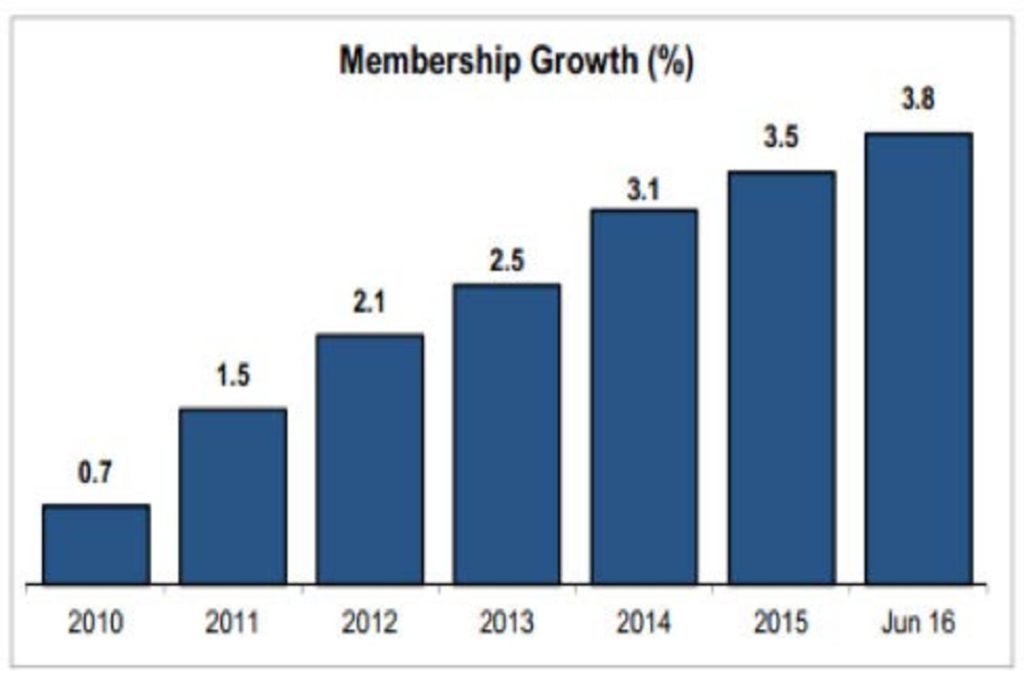

Since the Great Recession, the number of credit unions has decreased from 7,486 in 2010 to 6,143 in 2015,51 mostly due to mergers of small credit unions with larger ones. On the bright side, the annual rate of growth in memberships has increased year on year (see the chart above). Total credit union membership in 2015 is over 105 million or around 33 percent of the population,52 as many depositors are attracted by lower fees and the notion of moving their money out of a Wall Street big bank to a smaller, local credit union.

Governance

Participatory budgeting (PB): This democratizes the process of governmental budgeting by giving local residents an official say in where public money should go. Porto Alegre in Brazil provides one of the first and most prominent examples of participatory budgeting, where communities have been involved in city budgeting since 1989. The model has spread to cities in the US, the UK, Canada, India, Ireland, Uganda, and South Africa. There are PB projects in San Francisco and Vallejo, California, St. Louis, Missouri, Chicago, New York City, Boston, and Cambridge, Massachusetts. As of 2016, residents in various cities decided how to spend $98,000,000 on 440 local projects, including: adding bike lanes to city streets, supporting community gardens, purchasing a new ultrasound system at a hospital, adding heating stations to train platforms, and starting a community composting facility. PB encourages people to become more engaged in local issues, build community connections, learn about how the budgeting process works, and practice direct democracy. It has a track record of channeling increased resources to meet the needs of low income and marginalized communities.

The Commons movement: This seeks to protect and promote resources that we hold in common. Commons proponent Jay Walljasper defines the commons as:

…a wealth of valuable assets that belong to everyone. These range from clean air to wildlife preserves; from the judicial system to the Internet.Some are bestowed to us by nature; others are the product of cooperative human creativity.53

Examples of socially created commons include resources such as Wikipedia and free software, as well as parks, squares, and other public spaces where people come together to play, relax, and engage in social activities. Natural resources such as forests, oceans, clean air, and water are commons that need to be managed to protect the welfare of all, not just the rich and powerful. A commons does not mean a free for all, but rather requires governance that ensures equitable and responsible use.

Conclusion

We stand at the brink of disaster most of which is of our own making.The current economic system is killing us and the planet. To survive, we need a fundamental transformation from an economy that is premised on homo economicus—calculating, selfish, competitive, and acquisitive—to a system that is also premised on solidarity, cooperation, mutualism, altruism, generosity, and love. These are the values that the solidarity economy seeks to build upon. As we human beings practice and live more fully with these values, we are better able to realize the better angels of our nature. There is a strong and diverse foundation upon which to build that stretches across the globe. If these “imaginal cells” can recognize each other as pieces that are engaged in the same transformative project, then we can achieve a metamorphosis of our economy and society, where the welfare of people and planet are of the greatest import. This shift toward the solidarity economy may enable us to pull back from the brink.

NOTES:

- 1. On the Sixth Extinction, see: Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (New York: Picador, 2014).

- 2. Jean Louis Laville, “The Solidarity Economy: An International Movement,” RCCS Annual Review 2 (October 2002); Luis Razeto, “Factor C’: la Solidaridad Convertida en Fuerza Productiva y en el Factor Económico [Factor C: The Force of Solidarity in the Economy],” 1998 and Luis Razeto, Interview With Luis Razeto. Interiew by Esteban Romero. http://cborowiak.haverford. edu/solidarityeconomy/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2013/07/Interview-with-Luis-Razeto_May-2010.pdf.

- 3. Jose Luis Coraggio, “Territory and Alternative Economies,” Universitas Forum 1.3 (2009): 6.

- 4. RIPESS, “Global Vision for a Social Solidarity Economy: Convergences and Differences in Concepts, Definitions and Frameworks,” February 2015, http://www.ripess.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/RIPESS_Global-Vision_EN.pdf.

- 5. Nancy Folbre, Valuing Non-market Work, UNDP Human Development Report – Think Piece, 2015, folbre_hdr_2015_final.pdf.

- 6. Neoliberalism is a particular model of capitalism that advocates minimizing the role of the state in promoting the common good in favor of giving free rein to big business. Policies include privatization, de-regulation, cutbacks in social welfare programs, and “free” trade, though in reality there is a great deal of flexibility regarding these positions depending on what is beneficial to big business.

- 7. Esteban Romero, “The Meanings of Solidarity Economies. Interview with Luiz Razeto,” May 2010, http://cborowiak.haverford.edu/solidarityeconomy/resources-for-researchers/theorizing-social-and-solidarity-economy/interviews-with-louis-razeto/.

- 8. Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Thought and Practice (State College, PA: Penn State University Press, 2014).

- 9. RIPESS, Global Vision, 6.

- 10. National Plan for Good Living 2009–2013: Building a Plurinational and Intercultural State, Summarized Version, The Republic of Ecuador. National Development Plan, Quito, Ecuador, 2010. p6, http://www.planificacion.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2016/03/Plan-Nacional-Buen-Vivir-2009-2013-Ingles.pdf.

- 11. Shannon Biggs, Rights of Nature: Planting the Seeds of Change, San Francisco: Global Exchange, 2012, http://www.globalexchange.org/sites/default/files/RONPlantingSeeds.pdf.

- 12. Economics: Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011); Amartya Sen, “Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioral Foundations of Economic Theory,” Philosophy & Public Affairs 6:4 (1977): 317–344; Richard H Thaler, “From Homo Economicus to Homo Sapiens,” Journal of Economics Perspectives 14 (2000): 133-141; Robert J. Shiller, Irrational Exuberance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); Anthropology: Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation (Boston: Beacon Press, 1957); Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (Chicago: Aldine-Atherton, 1972); Clifford Geertz, Agricultural Involution: The Process of Ecological Change in Indonesia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963); Biology: Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants, and Natural Selection (New York: Pantheon, 1999); Joan Roughgarden, The Genial Gene: Deconstructing Darwinian Selfishness. (University of California Press. Berkeley CA, 2009); Rilling J, Gutman D, Zeh T, Pagnoni G, Berns G, Kilts C., “A neural basis for social cooperation,” Neuron 2002 Jul 18;35(2):395-405.

- 13. Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Vol. 1 (London: George Bells and Sons, 1908).

- 14. Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research 1.3 (2009): 243–53.

- 15. Elinor Ostrom, “Collective Action and the Evolution of Social Norms,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14.3 (2000): 137-58; Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University, 1990).

- 16. Ferris Jabr, “How Does a Caterpillar Turn Into a Butterfly?,” Scientific American, August 10, 2012, http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/caterpillar-butterfly-metamorphosis-explainer/.

- 17. Norie Huddle, Butterfly (New York: Huddle Books, 1990).

- 18. Jeremy Rifkin, End of Work, The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era (Putnam, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1995).

- 19. Eckart Ehlers and Thomas Krafft, Earth System Science in the Anthropocene: Emerging Issues and Problems (Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2006).

- 20. Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction.

- 21. There are lots of illustrations of the prisoner’s dilemma. Here is one user-friendly video: “What Is the Prisoner’s Dilemma?” Scientific American, 6/5/12, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jUTWcYXVR5w.

- 22. RIPESS, Global Vision. op. cit., p. 16.

- 23. Rights of Nature, Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, http://celdf.org/how-we-work/education/rights-of-nature/.

- 24. On the French legislation, see: “The 2014 Law on Social and Solidarity Economy: France.” European Commission, 2014, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/socialinnovationeurope/en/directory/ france/news/2014-law-social-and-solidarity-economy-%C3%A9conomie-sociale-et-solidaire-%E2%80%93-ess-en.

- 25. There is a considerable degree of confusion about and conflation of social economy and solidarity economy. RIPESS uses the term social solidarity economy which is admittedly confusing, but the RIPESS Charter makes it clear that its meaning is the solidarity economy and the intent is systemic transformation. The use of both social and solidarity is a matter of history and a marriage of convenience.

- 26. “The Social Economy,” Brussels: CEPCMAF, 2002, http://www.amice-eu.org/userfiles/ file/2007_08_20_EN_SE_charter.pdf.

- 27. Emily Kawano, “Social Solidarity Economy: Toward Convergence across Continental Divides.” UNRISD. February 26, 2013, http://www.unrisd.org/unrisd/website/newsview.nsf/%28httpNews%29/F1E9214CF8EA21A8C1257B1E003B4F65?OpenDocument.

- 28. Euclides Mance, “Solidarity-Based Productive Chains,” Curitiba, Novermber, 2002, http://solidarius.com.br/mance/biblioteca/cadeiaprodutiva-en.pdf.

- 29. Ana Esteves, “Grassroots Mobilization, Co-production of Public Policy and the Promotion of Participatory Democracy by the Brazilian Solidarity Economy Movement,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Sociology, Brown University, 2011.

- 30. “Solidarity Economy Map and Directory,” Solidarity Economy Mapping Project, http://solidarityeconomy.us/.

- 31. Anne Field, “More Cities Get Serious About Community Wealth-Building,” Forbes, November 10, 2015, http://www.forbes.com/sites/annefield/2015/11/10/more-cities-get-seri-ous-about-community-wealth-building/#3754fc4151c2; Jennifer Jones Austin, “Worker Cooperatives for New York City: A Vision for Addressing Income Inequality,” Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies, January 2014, http://fpwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Worker-Cooperatives-for-New-York-City-A-Vision-for-Addressing-Income-Inequality-1.pdf.

- 32. History of RIPESS, RIPESS website, http://www.ripess.org/about-us/history-of-ripess/?lang=en.

- 33. “Seven Cooperative Principles,” National Cooperative Business Association, https://www.ncba. coop/about-us/organization/7-cooperative-principles.

- 34. Lise Bond et al., “Survival Rate of Cooperatives in Quebec,” Quebec Ministry of Industry and Commerce, 1999; Carol Murray, “Co-op Survival Rates in British Columbia,” British Columbia Cooperative Association, 2011, http://auspace.athabascau.ca/handle/2149/3133.

- 35. Alyssa Davis and Lawrence Mishel, CEO Pay Continues to Rise as Typical Workers Are Paid Less, Economic Policy Institute, Issue Brief 380 ( June 12, 2014), http://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-continues-to-rise/.

- 36. Nina Misuraca Ignaczak, “It Takes an Eco-system: The Rise of Worker Cooperatives in the US,” Shareable, July 16, 2014, http://www.shareable.net/blog/it-takes-an-ecosystem-the-rise-of-worker-cooperatives-in-the-us.

- 37. Juliet Schor, True Wealth: How and Why Millions of Americans Are Creating a Time-Rich, Ecologically Light, Small-Scale, High-Satisfaction Economy (New York: Penguin Group, 2011).

- 38. New Work New Culture website, http://newworknewculture.org/.

- 39. Esha Chhabra, “The 3D Printed Car That Could Transform the Auto Industry: On Sale in 2016,” Forbes, 12/30/15, https://www.forbes.com/sites/eshachhabra/2015/12/30/the-3d-printed-car-that-could-transform-the-auto-industry-on-sale-in-2016/#1e1f95003595.

- 40. Mark Molloy, “This Incredibly Cheap House Was 3D Printed in Just 24 Hours,” The Telegraph, 3/3/17, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2017/03/03/incredibly-cheap-house-3d-printed-just-24-hours/.

- 41. Nathan McAlone, “This College Student 3D Printed His Own Plastic Braces For $60—And They Actually Fixed His Teeth,” Business Insider, 5/19/16, http://www.businessinsider.com/college-student-3d-prints-plastic-braces-for-60-2016-5.

- 42. W. Wuthrich, “Cooperative Principle and Complementary Currency,” trans. Philip Beard, 2004, http://monetary-freedom.net/reinventingmoney/Beard-WIR.pdf.

- 43. Steven McFadden, “Unraveling the CSA Number Conundrum,”The Call of the Land Blog, January 9, 2012, https://thecalloftheland.wordpress.com/2012/01/09/unraveling-the-csa-number-conundrum/.

- 44. “Community Land Trusts Lower Risk of Losing Homes to Foreclosure,” National Community Land Trust Network, March 17, 2009, http://www.homesthatlast.org/surveycommuni-ty-land-trusts-lower-risk-of-losing-homes-to-foreclosure/.

- 45. Rosalind Greenstein and Yesim Sungu-Eryilmaz, “Community Land Trusts: Leasing Land for Affordable Housing,” Land Lines, April 2005, p. 1 www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/community-land-trusts.

- 46. Emily Brown and Ted Ranney, “Community Land Trusts and Commercial Properties,” A Social Justice Committee Report for the Urban Land Institute Technical Assistance Program for Atlanta Land Trust Collaborative, p. 8.

- 47. “Contingent Workforce: Size, Characteristics, Earnings and Benefits,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, GAO-15-168R, April 20, 2015, http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/669899.pdf.

- 48. Trebor Scholz, “Platform Cooperativism: Challenging the Corporate Sharing Economy,” NYC: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, January 2016, http://www.rosalux-nyc.org/wp-content/files_mf/ scholz_platformcooperativism21.pdf.

- 49. Loconomics, http://loconomics.com/.

- 50. Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Taking the Predator Out of Lending: The Role Played by Community Development Credit Unions in Securing and Protecting Assets, Working Paper, Howard University, Center on Race and Wealth, August 2010, https://coas.howard.edu/centeronraceandwealth/reports&publications/0810-taking-the-predator-out-of-lending.pdf.

- 51. U.S. Credit Union Profile, Mid Year 2016, CUNA Economics & Statistics, p. 7.

- 52. Ibid, p. 5.

- 53. Jay Walljasper, “What, Really, is the Commons?” Terrain.org 27 (Spring/Summer 2011), http:// www.terrain.org/articles/27/walljasper.htm.

March 2018

___________________________________________________

Emily Kawano is Co-Director of the Wellspring Cooperative Corporation, which is seeking to create an engine for new, community-based job creation in Springfield, Massachusetts. Wellspring’s goal is to use anchor institution purchases to create a network of worker-owned businesses located in the inner city that will provide job training and entry-level jobs to unemployed and underemployed residents through worker-owned cooperatives. Kawano also serves as Coordinator of the United States Solidarity Economy Network. An economist by training, Kawano served as the Director of the Center for Popular Economics from 2004 to 2013. Prior to that, Kawano taught economics at Smith College, worked as the National Economic Justice Representative for the American Friends Service Committee and, in Northern Ireland, founded a popular economics program with the Irish Congress of Trade Unions.

Emily Kawano is Co-Director of the Wellspring Cooperative Corporation, which is seeking to create an engine for new, community-based job creation in Springfield, Massachusetts. Wellspring’s goal is to use anchor institution purchases to create a network of worker-owned businesses located in the inner city that will provide job training and entry-level jobs to unemployed and underemployed residents through worker-owned cooperatives. Kawano also serves as Coordinator of the United States Solidarity Economy Network. An economist by training, Kawano served as the Director of the Center for Popular Economics from 2004 to 2013. Prior to that, Kawano taught economics at Smith College, worked as the National Economic Justice Representative for the American Friends Service Committee and, in Northern Ireland, founded a popular economics program with the Irish Congress of Trade Unions.

Go to Original – thenextsystem.org