A Distant Flickering Light: The Hibakusha Peace Movement (Part 2)

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION, HUMAN RIGHTS, TRANSCEND MEMBERS, WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, ANGLO AMERICA, ASIA--PACIFIC, MILITARISM, 20 Aug 2018

Robert Kowalczyk – TRANSCEND Media Service

[The United States detonated two nuclear weapons over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively.] – Read Part 1 Here

20 Aug 2018 – An Interview with Kazuyo Yamane, Associate Professor of Peace Studies (retired) Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan

Is the Hibakusha Peace Movement fading? Why or why not?

The Hibakusha are growing older and older and it’s becoming more difficult for them to talk about their atomic bombing experiences to others compared to before. Now there is a project entitled, “No More Hibakusha Memory Center” which was established to preserve their memories for younger generations. Both Professor Ikuro Anzai and I are board members, so we have had meetings in Tokyo to discuss how to raise funds to make a proper archive of the past.

A great number of individuals and various groups have been collecting materials related to the Hibakusha Peace Movement. As the Hibakusha pass away, their families retain writings, photographs, recordings and other precious resources related to their memories of the bombing. These need to be collected and preserved in such an archive. Also, the Hibakusha need to preserve and share their past and current health records, not only for themselves but also for their descendants who someday may have physical issues related to the bombings.

In addition, there are second and third generation Hibakusha groups that are active in various ways. One of these is to be reassured that they will have free medical check-ups not only once a year as it is now, but also whenever it may be necessary, as this is still a serious concern. Being of the second generation of survivors, I too share these concerns for myself and for my descendants. We believe that the second to fourth generations should also be given attention, and, when necessary, receive free medical care.

I understand. Have some of the second-generation survivors shown physical ill effects from the bombings?

This is very difficult to clearly demonstrate. There is a United Nations scientific committee on the effects of the radiation and they say that there is no influence of radiation upon subsequent generations. But in reality, we Hibakusha know that there have been ill effects. For example, first children born of a first generation Hibakusha parent or parents have unexpectedly died for some reason, and we Hibakusha have wondered about the true reason for the early deaths. Also there seems to be an unusually high number of descendants who have contracted leukemia. So, there may be some issues related to a lack of immunization from radiation. Concerns such as these are a reality for many of the descendants.

I totally understand the importance of these matters. However, I would like to now focus on the Hibakusha Movement for Peace that relates to their slogan,

“No More Hiroshima. No More Nagasaki.” Is that fading?

Well, as I’ve said, those who have lead the movement are now growing older. But I think their movement is continuing. The best example is that ICAN was awarded the Noble Peace Prize. I think behind that there was the Hibakusha Peace Movement for peace education. I think ICAN members were moved and learned how dangerous nuclear weapons are from the Hibakusha. Because of that, they started to work for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

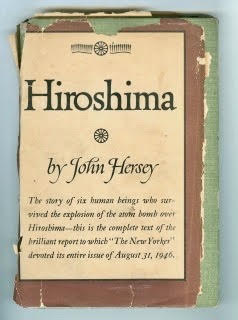

I’d like to read this statement by John Hersey, the author of the celebrated reportage of the atomic bombing, Hiroshima. “What has kept the world safe from the bomb since 1945 has not been deterrence, in the sense of fear of specific weapons, so much as it’s been memory. The memory of what happened at Hiroshima.” And I always add “and Nagasaki.” Is that memory no longer as important as it was, say ten years ago?

I think it’s still important because we had the Fukushima nuclear accident and the same thing is happening in Fukushima. For some reason, the people in Fukushima are called “Hisaisha” (meaning sufferers or victims) not “Hibakusha” (meaning radiation victim). Of course there are many “Hibakusha” in Fukushima, but the media does not use that term for them.

The Japanese term “Hisaisha” means victims of tsunami or any other type of disaster. It is a general term that means “sufferers” or “victims”. It makes no reference to the effects of nuclear radiation at all.

Then who chose that Japanese word?

The media. The media reports use that word. However, the present true situation of Fukushima is not reported.

Then you would prefer that the people who suffered in Fukushima should all be termed Hibakusha?

Yes, I do. But the people there don’t want to think of themselves as “Hibakusha”.

Can you please tell me the exact meaning of Hibakusha in English?

Let me check my dictionary to be sure. It says, “a person who was exposed to radiation from an atomic bomb or a hydrogen bomb or nuclear accidents.”

Thank you. Allow me get back to the meetings of the following generations of Hibakusha. Is there anything being done at these meetings to continue the Hibakusha Peace Movement?

Yes. For example, since 1958 there has been a Peace March from Tokyo to Hiroshima and Nagasaki so this year is its 60th anniversary. They actually walk those long distances over many days in early August leading them down to the two atomic bombed cities for the Commemoration ceremonies. Not only Hibakusha but young people who have been influenced by the Hibakusha also attend this March. The main problem is that it is not reported in the media. The Hibakusha also have attended numerous world conferences against atomic or hydrogen bombs and often speak at these meetings.

There is also a movement called Six-Nine Action, in which, on the sixth and ninth days of ever month, which of course coincides with the two dates of the bombings, Hibakusha collect signatures on the streets of the cities where they reside and other cities. That happens, for example, at Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto or in other locations across Japan. And since 2016, citizens have worked on The Hibakusha Appeal for the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons by 2020 at the UN General Assembly.

I’d like to return to Hersey’s statement. Is he not right that we should all support the continuation of the Hibakusha Peace Movement in one way or the other? Or, to put it another way, will ICAN alone solve the nuclear weapons problem without the active memory of the Hibakusha?

I think because of the Hibakusha’s testimony the people in ICAN learned very much about the danger of nuclear weapons. I think this issue is universal. It is not just about the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It’s universal because there are so many nuclear weapons in the world, so many nuclear power plants in the world, which means all the people, plants or animals would be affected if there is a nuclear accident like Fukushima or a new smaller and more effective nuclear weapon is used by the US, for example. As you know, they are both much more powerful and of a smaller size than ever before.

Excuse me. I would like to address a matter that I consider important. It clearly seems to me that what the Hibakusha have done is nonpolitical; no fingers of blame were ever pointed publicly in any direction throughout the Hibakusha Peace Movement. The issue of the nuclear power plants is quite a different matter. It’s not one of horrific bombing of civilians but rather a social issue of choice, to be decided through a democratic process. I also fully understand that all nuclear power plants are potential nuclear bombs that could easily be targeted with conventional weapons. However, I do not think it is right to confuse the 73-year Hibakusha Peace Movement with these current ongoing political considerations concerning nuclear power.

Yes, I understand. Please remember that I just came back from attending a conference in Fukushima on nuclear power plants so it is still fresh in my memory. Nuclear radiation is also a serious threat to humanity.

Yes, of course. May we return once again to ICAN?

Fine. Please do.

Do you feel that it is or is not important now for such global organizations such as ICAN, with its 468 affiliates in 101 countries, to represent the Hibakusha Peace Movement?

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons logo and map is from the ICAN website on August 15, 2018.

Yes, I think that especially after ICAN was awarded the Noble Peace Prize it means that people all over the world would listen to them more than they did before. I think it’s important for ICAN to unite various kinds of organizations who are against nuclear weapons. Especially the Hibakusha organization known as Nihon Hidankyo which has its own website, both in Japanese and English.

From the best of your knowledge what is the current state of education in Japan about the Hibakusha. Is it constant or is it increasing or decreasing?

I think it is important to teach others what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as other Hibakusha such as native Americans who were opposed to radiation in uranium mining, victims of nuclear tests, nuclear accidents and so forth, comprehensively. I’m afraid that such education is insufficient. When I checked governmentally approved high school textbooks for the coming year at an exhibition put on by the Kyoto Central Library. Aside from the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I was also interested in the explanations of the Nanjing Massacre, nuclear tests and nuclear power issues.

It seems that after World War II, the teachers themselves wanted to promote peace education, however young teachers now giving instructions are themselves not educated enough about these issues. This of course is problematic. These days there is still some information about the atomic bombings, but issues such as the Nanjing Massacre or the Korean women who were forced to work as sex slaves are ignored. In the early 1990’s we could still find such references, but now, due to rising nationalism, students are not taught as deeply even about Hiroshima and Nagasaki as they were before.

You are seeing these issues slowly being erased from the textbooks.

Yes. Even if they do appear, teachers tend to say, “Well these kinds of things will not be on the entrance exams for universities and we can just skip over them.” Moreover, Japanese history is not a compulsory subject; world history is, but not Japanese. When I teach peace studies at Ritsumeikan University, it is shocking that Japanese students are so ignorant about modern or current history.

Perhaps the same could be said for education in the U.S. or elsewhere. But could you give me an example of that in your classes?

Well, in a Peace Studies class there were students from about 17 countries and they were asked to discuss Korean issues, for example. And when a Korean student asked questions to a Japanese student, he was so ignorant of the issue that he couldn’t say anything.

On the other hand, there was a Japanese student from Ritsumeikan High School who had studied a thick school textbook, not the one screened by the Ministry of Education, but one written by a team of historians in China, Korea and Japan. So this student knew real history, including Japan’s aggression towards other countries or Japan’s colonization of Korea, etc. Therefore he could communicate effectively with other students including those from Korea.

Since students from China and Korea come to study at Ritsumeikan University they have a good chance to get to know one another. For example, I took students from both Ritsumeikan and American University to Hiroshima and Nagasaki for about five years from 2011 to meet Hibakusha, including Mrs. Koko Kondo. So there were American, Japanese, Korean and Chinese students on those trips to attend the commemoration ceremonies in the two cities.

The American students, and also the Chinese and Korean students, first thought the bombings were good because they ended the war. However, after listening to Mrs. Koko Kondo or by visiting the Hiroshima Memorial Peace Museum and the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, their concepts of history were totally changed.

In addition, when students visited the Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Peace Museum the Japanese students were shocked to see the Japanese aggression in China and Korea since they did not learn such things at high school. Students from these four countries were able to exchange their thoughts and ideas and they eventually began to relate to each other just like family members do; they all became very good friends by the end of the visits.

That’s very important. For everyone, and especially the young, to understand that human beings are human beings, whether they are Japanese in China or Americans in Vietnam. All human beings are capable of being used for war.

I remember a Korean female student who met and listened to Mrs. Koko Kondo and eventually shed tears and hugged her because her talk was so moving. The student used to think that the atomic bombing was so good because it ended Japan’s colonization of Korea, but after the visits she could realize that it was not right and she could see the other side, what had happened to the Japanese people. So we really need such peace education.

I couldn’t agree more. Then let me ask you this, what do you hope to do in coming years to further, in your own way, a deeper understanding of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

There is a peace education project in the Peace Studies Association of Japan and we want to use workshops for students or citizens to promote peace education. Young people like animation. So we created an animated film on ethnic issues that are related to human rights and even made an English version. And now we are trying to publish a book that contains a DVD of animation based on Johan Galtung’s theories of peace studies. I believe such a tool will be useful because it sometimes is not enough for students to merely listen to a lecture about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, for example. However, if there is a workshop and each individual needs to get involved and express their ideas and think what we all should do for the abolition of nuclear weapons, I believe the use of animation and those kinds of materials could make it much more effective.

Animation would also be effective because both young and old can enjoy it, and after watching an animated feature they can all discuss the issues it presents. At Kyoto Museum for World Peace we had a workshop for graduate students from various countries and they were asked to make an exhibition on an issue in which they were interested, and they also were asked to make a Peace Game with the help of members of the Department of Image (Eizo Gakubu) of Ristumeikan University.

As you know, war games are very popular not only in Japan but also in many countries. Well in war games, the more one can kill, the more points he or she gets. But in Peace Games, the more individuals cooperate with one another, the more points they get. The graduate students did a good job on those games, so I suggested that they present a paper at the International Conference of the INMP (International Network of Museums for Peace) in Belfast. And one student did! An American scholar from Dayton International Peace Museum in Ohio was really impressed and agreed that there should be more Peace Games than war games. So I’m sure there are various ways to promote Peace Education rather than just giving a lecture.

That is all very fine and hopeful.

I have one last question. In your academic speeches, presentations and discussions at international conferences outside of Japan, how many of those that you have met know about the Hibakusha Peace Movement?

Many simply do not know about the Hibakusha and their peace movement. However, once they know about them they begin to change their minds and better realize the dangers of nuclear weapons. Actually, I know two Americans whose lives were changed after visiting the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

One is David Krieger, who visited the museum when he was young and was so shocked that he decided to work for the abolition of nuclear weapons by founding The Nuclear Age Peace Foundation.

And the other is Professor Roy Tamashiro of Webster University in the United States who recently retired. When he first visited Hiroshima, he was wondering what he should do about the Vietnam War, but after visiting the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum he became a conscientious objector. So I realized that the peace museum in Hiroshima is so very powerful. It can change people’s lives and we simply do not know how long it may take. It can be two or three months, or 20 to 30 years later. So I think peace education is both very interesting and also very difficult to clearly evaluate.

So we can say that visiting and seeing what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki heightens the awareness of what life is about and what the dangers are, an experience that changes lives. In that sense, to lose the Hibakusha Peace Movement is to lose a most important understanding of peace.

Yes, it is. Fortunately, however, there are many museums for peace in Japan, and as we can see by the efforts of the International Network of Museums for Peace, they are growing throughout the world. I trust they will do their best to preserve these memories for future generations. This has been a significant part of my life work and remains my continual hope.

Thank you very much Professor Yamane. It has been a pleasure and a reward to share this time with you.

You’re welcome.

___________________________________

All images are by Robert Kowalczyk, including images from the 2007 Commemoration ceremonies in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Robert Kowalczyk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. He is former Professor and Department Chair of the Department of Intercultural Studies in the School of Art, Literature and Cultural Studies of Kindai University, Osaka, Japan. Robert has coordinated a wide variety of projects in the intercultural field, and is currently the International Coordinator of Peace Mask Project. He has also worked in cultural documentary photography and has portfolios of images from Korea, Japan, China, Russia and other countries. He has been a frequent contributor to Kyoto Journal. Contact can be made through his website portfolio: robertkowalczyk.zenfolio.com.

Robert Kowalczyk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. He is former Professor and Department Chair of the Department of Intercultural Studies in the School of Art, Literature and Cultural Studies of Kindai University, Osaka, Japan. Robert has coordinated a wide variety of projects in the intercultural field, and is currently the International Coordinator of Peace Mask Project. He has also worked in cultural documentary photography and has portfolios of images from Korea, Japan, China, Russia and other countries. He has been a frequent contributor to Kyoto Journal. Contact can be made through his website portfolio: robertkowalczyk.zenfolio.com.

Kazuyo Yamane, a second generation Hibakusha, is an Associate Professor of Peace Studies at Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto (retired). She was Vice-Director of the Kyoto Museum for World Peace and is a board member of The International Museums for Peace (INMP) and is active in many other peace organizations.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 20 Aug 2018.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: A Distant Flickering Light: The Hibakusha Peace Movement (Part 2), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

One Response to “A Distant Flickering Light: The Hibakusha Peace Movement (Part 2)”

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION:

- The Visionary Palestinian Peace Plan for Israel and Gaza That You’ve Never Heard of

- TFF Portfolio for True Peace in Ukraine

- President Putin Reiterates the 14 Jun 2024 Conditions for Ending the War with Ukraine

HUMAN RIGHTS:

- Human Rights in a Divided & Dangerous World

- Landmark Ruling Finally Brings Justice for Survivors of Wartime Sexual Violence in DRC

- 'Brutal Sadism:' Israel Bans Gazans from Entering Mediterranean Sea Under Pain of Death

TRANSCEND MEMBERS:

- Albert Einstein Foresaw the “Catastrophe" That Is Israel and Declined to Be President of Zionist Losers

- A Mnemonic Framework for Understanding Communication Challenges

- The Weaponizers of Antisemitism Have Come for the American Psychological Association

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION:

ANGLO AMERICA:

- ‘We Want It Back’: Trump Asserts U.S. Claims to Venezuelan Oil and Land

- Judge, Jury, and Executioner: On U.S. Assassination Policy 1975-2025

- Everything the Trump Administration Is Doing in Venezuela Involves Oil and Regime Change—Even if the White House Won’t Admit It

ASIA--PACIFIC:

- Genocide Emergency: Xinjiang, China 2025

- Prisons as Sites of National Reconciliation or Continuing Hells

- Japan’s Push Toward “Aggressive Militarist Ambitions” Raises Alarms for Asia-Pacific and World Peace

MILITARISM:

Much kudos to Professors Yamane and Kowalczyk for this informative, provocative and inspiring interview.

One peccadillo: I wish there had been a definition of ICAN a bit sooner. I’m chagrined to admit that I didn’t know about this important organization–and didn’t know what the acronym stood for.

Responding to Professor Kowalczyk’s carefully constructed–even probing–questions, Professor Yamane enlightened the reader about the current status of Hibakusha survivors in Japan, and the imperative need for more peace activism, as well as more information about nuclear dangers from wars or Fukushima-type disasters. Professor Yamane stressed the need to reform and update current educational methodologies to meet the needs of a rapidly globalizing world consciousness. Why not have computer “Peace Games” instead of “War Games” for example? Use anime to connect to children. Encourage international meetings of students: not to fix “blame” for the horrors of the past, but to highlight the dangers to our future as interconnected beings on a fragile planet.

Americans are becoming more familiar with the idea of “fake news” (and some even wonder about “fake history”!) Both professors touch on the idea of media misdirection: the media’s failure to take notice of Hibakusha peace marches, and other kinds of peace-activism.

Santayana’s poignant warning still rings true: Those who do not learn the lessons of past failures and tragedies are bound to repeat them! Professor Yamane notes: “It seems that after World War II, the teachers themselves wanted to promote peace education; however, young teachers now giving instructions are themselves not educated enough about these issues. This of course is problematic. These days there is still some information about the atomic bombings, but issues such as the Nanjing Massacre or the Korean women who were forced to work as sex slaves are ignored. In the early 1990’s we could still find such references, but now, due to rising nationalism, students are not taught as deeply even about Hiroshima and Nagasaki as they were before.”

And:

“When I teach peace studies at Ritsumeikan University, it is shocking that Japanese students are so ignorant about modern or current history.”