In Search of Meaning: Thoughts on Belief, Doubt and Wellbeing

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 24 Sep 2018

A Twenty-Year Anniversary Reflection

September 20, 1999 – September 20, 2018«Plus Ca Change, Plus C’est La Meme Chose »

— Jean Baptiste Alphonse Karr, 1849

Abstract

This paper, published first in 1999, discusses the spiritual consequences for health and wellbeing associated with a dialogical tension between meaning-making and doubt. Meaning-making is pursued via various complex belief systems: worldviews, philosophies, religions, ideologies, mythologies, and “spiritual paths. These belief systems provide a sense of purpose, direction, predictability, and control. In doing so, discomforting stresses and tensions associated with uncertainty or “not knowing,” afflicting health and wellbeing, are reduced, released, or eliminated. Optimal health and wellbeing, however, requires meaning-making efforts tolerated doubt.

Dialogical stresses and tension between belief systems and doubt promote an enhanced sense of spiritual well-being characterized by mind-enhancing experiences of awe, reverence, harmony, connection, and unity, resulting in releasing body and mind from existing assumptions, and promoting a continuing condition and state of revival, renewal, and personal growth.

(This paper polishes and refines prior thoughts after twenty-years. The passage of twenty years provokes thoughts about what has changed, and what remains constant. Obviously, the world has changed politically, economically, culturally, and morally in many ways. What has not changed, in my opinion, however, is the important inherent human impulse for meaning-making requiring the tolerance and acceptance of doubt. In the presence of the comforts and satisfactions of certainty, pursued in religious, ideological, and philosophical, belief systems, doubt remains essential).

Introduction

Not non-existent was it, nor existent was it at that time; there was not atmosphere nor the heavens which are beyond. What existed? Where? In whose care? Water was it? An abyss unfathomable? . . .

Who after all knows? Who here will declare from whence it arose, whence this world? Subsequent are the gods to the creation of this world. Who then, knows when it came into being?

This world – whence it came into being, whether it was made or whether not – He who is its overseer in the highest heavens surely knows – or perhaps he knows not.Creation Hymn – X. 129

Selections from the Rgveda

Maurer, W. (1986, p. 285)

In Search of Meaning: The Endless Dance of Belief and Doubt

Asserting and Refuting

The inspiring words from the Rgveda’s Creation Hymn X. 129, written more than 3500 years ago, document and affirm the age-old human quest for personal meaning. For me the special enchantment of the Creation Hymn resides in its delicate juxtaposition of the human impulse to know (i.e., to make sense of the world) and to doubt (i.e., to question that which is known and accepted). What profound words: “He who is its overseer in the highest heavens surely knows, or perhaps he knows not.”

The process of “asserting” yet “refuting” expressed in the Creation Hymn, captures the essential force behind human progress through the ages. It is an adaptive dialectic enriching and extending human possibilities and potential. Even as we reach a hard-won conclusion, doubt emerges to move us toward yet other possibilities. Unlike other beings whose behavior is fixed by reliance upon instinct and reflex, human beings have the capacity for reflective thought. We can reach a conclusion in one moment and modify it a moment later.

The human impulse to know and to doubt provides an insight into the origins and nature of our religious, philosophical, and mythological, and ideological belief systems. These spring from our impulse to know and to doubt.

There is within our nature an imperative to ask why, and to order our answers in increasingly complex systems of beliefs designed to reduce our uncertainties and to increase our sense of control and mastery of the world. This is a reflexive and automatic response. So too is our inclination to doubt. Yet, because of the discomfort associated with uncertainty, it is often necessary for us to exert greater conscious effort so that we may move beyond reflexive acceptance toward the discomforts associated with disbelief.

Thus, the human mind — that experienced sense of intention and agency emerging from the simultaneous interaction of organism and environment — establishes order, coherence, and meaning from the vast array of stimuli flooding the senses. At some point, within a cultural context, it constructs elaborate and ritualized beliefs and/or practices regarding human meaning providing us with a sense of certainty, comfort, and significance from the vicissitudes of life’s experiences. The process of meaning-making and doubting has important implications for health and wellbeing.

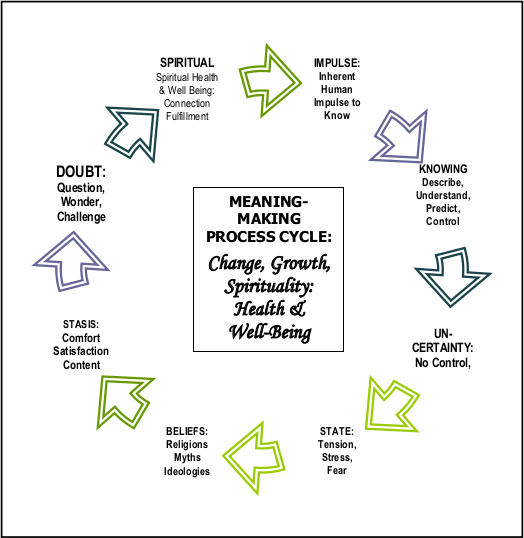

Chart 1 displays the process cycle. As Chart 1 indicates, the meaning-making process begins with the inherent human impulse to know and by making sense of the myriad stimuli imposed on the brain. The process imposes order and organization, often times relying on macro belief system processes (e.g., religion, ideologies)

Chart 1: Meaning-Making Process Cycle

Chart 1: Meaning-Making Process Cycle

Meaning, Doubt, and Belief Systems

- Renewed Interest in Human Meaning

The pursuit of meaning is, in many respects, the most human of behaviors — the defining characteristic of our species homo sapiens. Within the past few decades, there has been a renewed interest in the study of human meaning among clinicians and scientists (e.g., Richards & Bergin, 1997; Thorsen, 1998; Wong & Fry, 1998). Wong & Fry (1998), in the introduction to their exceptional book, The Human Quest for Meaning, write:

After a hundred years in the wilderness of philosophical and religious discourse, the concept of personal meaning has emerged as a serious candidate for scientific research and clinical study. . . . There is now a critical mass of empirical evidence and a convergence of expert opinions that personal meaning is important not only for survival but also for health and wellbeing. (p. Wong & Fry, pp. xvii) (Wong & Fry have published a new edition in 2018)

Contemporary theorists agree the pursuit of meaning is critical for our adaptation and adjustment (e.g., Klinger, 1998; Maddi, 1998). These theorists build upon the contributions of previous theorists in psychology including Allport (1955), Frankl (1946/1959), Fromm (1947), Kelly (1956), Maslow (1968), and May (1967). Viktor Frankl (1905-1998) is perhaps the most notable figure in our century to call attention to the human quest and need for meaning.

Frankl (1946/1959), a Nazi concentration camp survivor and the developer of Logotherapy (Frankl, 1973), in his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, he argues that meaning is the central motive of human life. He suggests that above all else, our capacity to ask why with regard to our existence indicates that “meaning” is at the core of our health and wellbeing.

For Frankl, human survival depends on finding and preserving “meaning” amidst the madness of our world, and on filling the “existential vacuum.” But, more importantly for Frankl, “meaning” is not something that occurs reflexively within the human mind, but rather something demanding an active pursuit — the “will to meaning” — in which we actively seek a meaning in life.

In Frankl’s opinion, the “will to meaning” is a primary human motive that supersedes the pursuit of pleasure and power. Wong (1998) points out Frankl’s life epitomizes Nietzsche’s dictum: “He who has a why to live for, can bear almost anything. Human history is replete with examples affirming Nietzsche’s dictum. Frankl’s views have often been considered more of a “secular religion” (see Wong, 1998, p. 400) than a science, and for this reason, they have not always been popular among behavioral scientists.

Today, data is accumulating in support of Frankl’s views. For example, the recent book by Wong and Fry (1998) provides data from numerous studies of personal meaning based on quantitative (e.g., Personal Meaning Profile; Life Regard Index) and qualitative measures (e.g., personal narratives) that affirm Frankl’s assumptions.

- Brain and Meaning

Klinger (1998) argues the human quest for meaning is rooted within the brain itself, and that goal-striving is a biological imperative of all zoological organisms. He notes it is humankind’s cognitive and symbolic capacity elevating this biological drive to the transcendent experience of higher purpose and meaning (Wong & Fry, 1998). Indeed, Klinger (1998) concludes that failures to make meaning may have pathological consequences.

The highest calling of the brain, aside from its basic reflexive survival functions, is its efforts to generate meaning and purpose from the vast array of sensory-coded experiences our billions of brain cells accumulate. This accumulation process — this storage of lived experience — both supports our survival, and drives us forward in search of higher principles for organizing and connecting our acquired experience. Through memory and learning, continuities are established with our individual, collective, and cosmic past and imagined future.

Thus, the brain is more than a simple sensate mechanism for reflexively recording external and internal stimulation in organized substrates. The undamaged human brain not only responds to stimuli, it also organizes, symbolizes, and connects stimuli, and in this process, it generates an emergent pattern of meaning, facilitating our survival, growth, and development. These higher-order functions of the brain push us toward the pursuit of meaning, and with this, a felt sense of understanding, predictability, and transcendence.

Recent developments in neurosciences support the existence of intimate relationships between brain structures and processes and cognitive behavior. Each day new discoveries seem to appear regarding the neurological basis of consciousness, sensation, emotion, memory, and learning. It is estimated our brain possesses more than 15 billion neurons that work in organized units through trillions of complex vertical and horizontal connections. The structure of these cells — the cytoarchitectonics — and their myriad connections, constitute an essential element of human psychology (e.g., Damasio, 1994; Marshall & Magoun, 1998).

- The Inherent Impulse After Meaning

Efforts after meaning begin with the human brain’s inherent impulse to order, organize, and structure sensory data. This impulse, acted out within a cultural context, leads to the construction of higher-order cognitive beliefs, schemata, and information patterns that we associate with worldviews and various philosophies, religions, ideologies, mythologies. We move from simple information processing of sensory inputs to complex belief systems guiding and framing our lives, these are belief systems associated with existential concerns: purpose, hope, identity, life, death, self, choice, and morality. We cannot separate these existential concerns from human health and wellbeing.

The importance of establishing organized and systematic belief systems for our health and wellbeing cannot be denied, and although these vary considerably across individuals and cultures, they seem to be universal in their function of bringing comfort, purpose, direction, predictability, and control to our lives (e.g., Frankl, 1959; Richards & Bergin, 1997; Taggart, 1994). Taggart (1994) stated that:

. . . our belief systems are . . . the basis for our existence; they are symbol systems that enable us to derive meaning from a chaos of stimuli and instincts and to decode the mystery of our existence. Our separate core beliefs, whether secular or religious, anchor us in the dizzying vastness of the great unknown we call reality. (Taggart, p. 20)

Throughout history, humans have advanced numerous atheistic and theistic belief systems (see Sheinkin, 1986) replete with rituals, rites, ceremonies, and dogmas. At a personal and cultural level, these belief systems help position and root us within the mysteries of the cosmos. They order chaos, reduce complexity, and give purpose (e.g., Allport, 1950; Brown, 1994; Frankl, 1959; Richards & Bergin, 1997; Taggart, 1994).

Wong (1998) suggests that personal meaning has three components: cognitive (beliefs, schemas, making sense), emotional (feeling good, feeling fulfilled), and motivational (goal striving, purpose, incentive value). Referring to his model, Wong (1998) notes:

Thus, the structural definition of personal meaning is that it is an individually constructed, culturally-based cognitive system that influences an individual’s choice of activities and goals, and endows life with a sense of purpose, personal worth, and fulfillment. This definition identifies the key elements of meaningful existence, and indicates their interrelations. (Wong & Fry, 1998, p. 407).

The Importance of Doubt

Even as we seek to confirm and sustain core beliefs, there is, I believe, a simultaneous disposition to ponder, to question, and to doubt, whether the “truths” we prize are in fact more relative than absolute, more questionable than certain, and more temporal than enduring.

Humans seek meaning, but dislike doubt. The American philosopher Charles Peirce (1839-1914) noted human beings will tolerate many things — but not doubt. When faced with doubt, he claimed humans will often resolve the tensions by deferring to authority or simply maintaining their beliefs with renewed tenacity. Obviously, we must guard against this tendency. As Andre Gide reminds us: “Believe those who seek truth, doubt those who find it.”

Here, I also think of the words of Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), the famous Danish existential philosopher, who was concerned with the question of human choice and responsibility, and especially of our “fear of nothingness.” In one of his later books, A Sickness Unto Death, Kierkegaard (1849/1954) writes:

. . . the good is the opening toward a new possibility and choice, the ability to face into anxiety; the closed is the evil, that which turns away from newness and broader perceptions and experiences; the closed shuts out revelation, obtrudes a veil between the person and his own situation in the world. (Kierkegaard, p. 124)

Within the traditions of academic psychology, George Kelly (1956), with whom I had the privilege of studying, advanced a theory supporting Kierkegaard’s observations about the consequences of closed and open minds. According to Kelly (1956), the impulse to establish a set of organized beliefs about the world and our role in it, flows from our natural inclination to process information from the world about us for the purposes of describing, understanding, predicting, and controlling our lives.

Kelly contends we do this by establishing a system of super-ordinate and sub-ordinate cognitive constructs (i.e., templates) that emerge from our personal experience and that serve to mediate our reality.

Our perceptions of our world, and our responses to it, are dictated by our “constructs.” And most importantly, for Kelly it is through lived experience that our personal construct system is continually revised, adjusted, and reorganized. Thus, he notes, experience serves to modify the sub-ordinate/super-ordinate relationships of our personal construct system, yielding new perceptions of reality and alternative behavior patterns that keep us open to new possibilities.

Meaning, World Views, and Culture

Even as we speak of personal meaning at an individual level, it is essential to understand all individuals are embedded within cultural contexts. These contexts constitute the basis for socializing and for promoting ways of life across generations particular to a group of people. Culture is the context in which mind is acquired, and thus, mind reflects culturally constructed realities.

Defining Culture

Culture can be defined as:

Shared learned experience transmitted across generations for purposes of survival, adaptation, and adjustment. Culture is externally represented in such forms as artifacts (e.g., clothing, foods, technologies), roles (e.g., parents, mother, occupations), and institutions (e.g., family, religion, education, economic, etc.). Culture is represented internally in such forms as worldviews, values, beliefs, attitudes, consciousness patterns, epistemologies, cognitive styles.

Behavior cannot be separated from the cultural context in which it develops and is sustained. Culture influences all aspects of our lives, including our:

- Values, attitudes, beliefs, and standards of normality/abnormality, and morality;

- Notions of time, space, and causality (i.e., epistemology, ontology, praxiology);

- Patterns of human communications and social interaction (e.g., verbal, nonverbal, and para-verbal communications);

- Linguistic nuances and structures;

- Expressive styles and preferences in clothing, food, art, and recreation; a sense of aesthetics;

- Familial, marital, and child rearing practices and preferences;

- Preferred cognitive styles, and coping and problem-solving styles;

- Interpersonal relationship patterns, especially regarding authority, gender, elderly (i.e., social structure and social formation);

- The structure and dynamics of institutions such as the family, schools, government, religion, workplace, and social formation;

- Personal, racial, and social identities;

- Creative arts and artifacts (e.g., diet, food, dress, make-up)

- Our biological nature, including brain structures and processes.

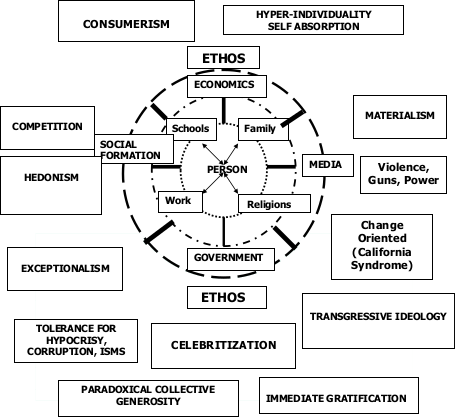

Cultural systems are generally constructed around an ethos, or set of core assumptions. These assumptions eventually find themselves represented in institutions (e.g., political systems, economic systems), activity settings (e.g., family activities, work activities), and personal behavior patterns.

Chart 2 provides a schematic of a prototypical cultural system using dominant group American core values as the Ethos. As Chart 2 indicates, an Ethos of individualism, materialism, competition, supported macrosocial and microsocial institutions, encourages these qualities, promote them via socialization. A contrasting ethos, valuing an unindividuated (collective) self, spirituality, and cooperation, will produce another socialization context.

Cultures vary in their concepts of selfhood or personhood (e.g., Marsella, Hsu, DeVos, 1985). Within the United States, the dominant cultural emphasis is placed on socializing an individual who is autonomous, detached, and independent. Health, wellbeing, and maturity are often equated with self-sufficiency and independence.

In many East Asian cultures, a collective or unindividuated self, is preferred. This self is considered to be inseparable from the group, and individual happiness and wellbeing are derived from meetings one’s social roles and expectations.

CHART 2: AMERICAN (USA) POPULAR CULTURE: Ethos, Macro, Micro, Psychosocial Socialization

CHART 2: AMERICAN (USA) POPULAR CULTURE: Ethos, Macro, Micro, Psychosocial Socialization

Chart 1 describes the process of the cultural construction of reality via the socialization process. Religions, life philosophies, and mythological belief systems reflect the essentials of our many and varied culturally constructed cosmological, epistemological, ontological, and praxiological orientations. Culturally, these orientational systems are embedded in our worldviews, the broader set of assumptions regarding our relations to god(s), nature, and one another. These differences in preferred views of selfhood help demonstrate the consequences of the cultural construction of reality.

Collective “Ethei” found in East Asian cultures have a strong Confucian orientation. Confucius (circa 551-479 BCE) advocated meeting one’s social obligations and responsibilities as a basic virtue. In meeting these obligations and responsibilities, one helps promote social harmony, civility, and conformity to virtuous standards (e.g., kindness, faithfulness, decorum, wisdom, and character). The worth and purpose of individuals is often assessed against their group and/or societal contribution.

Table 1:

Contrasting Prototypical USA and East-Asian

Cultural Patterns (Pre-Year 2000 Version)

DIMENSION CULTURE A CULTURE B

- SELF Individual/Collective Collective/Individual

- Maturity Independence Interdependence

- Style Assertive Deferent

- Orientation Product/Process Process/Product

- Communication Direct Indirect

- Mode Verbal Non-verbal

- Status Equality Hierarchical

- Effort Mastery Harmony

- Determinants Person/Status Destiny/Karma/Person/Status

- Traditions Change/New Preserve/Past

- Generations Distinct Continuous

- Knowing Fission Fusion

According to Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911) who fought against the domination of learning by the physical and natural sciences and their methods, our “world view” is a subjective, experientially derived/ set of beliefs developed “to resolve the enigma of life” (see Kluback & Weinbaum, 1957, p. 25). Table 1 present a listing of the steps involved in the cultural construction of reality. It begins with birth (actually it begins with the nature of the human brain and mind. The arbitrary designation of six steps describes the process.

TABLE 2 – THE CULTURAL CONSTRUCTION OF “REALITY”

- There is an inherent human impulse to describe, understand, predict, and control the world about us through the ordering of stimuli into complex belief systems that can guide behavior;

- The undamaged human brain not only responds to stimuli, it also organizes, connects, and symbolizes them, and in this process, it generates patterns of explicit and implicit meanings and purposes that promote survival, growth, and development;

- The process and product of this activity are to a large extent culturally generated and shaped through linguistic, behavioral, and interpersonal practices that are part of the socialization process;

- This storage of accumulated life experience, in both representational and symbolic forms, generates complex shared cognitive and affective organizational and process systems that create continuity across time (i.e., past, present, and future) for both the person and the group;

- Through the process of socialization, individual and group preferences and priorities are rewarded through chance and choice, thus promoting and/or modifying the cultural constructions of reality (i.e., epistemologies, cosmologies, ethei (ethoses), values, and behavior patterns);

- Reality is culturally constructed!

Worldviews (Weltanschauung): The Need for Meaning

Without a sense of purpose and meaning, as reflected in our philosophical, religious, and mythological belief systems, we would find ourselves confused, disoriented, and dislocated, an organism compelled to respond to each situation without a reason or rationale beyond immediate adaptation and adjustment. Societal life would be impossible, for it is the shared beliefs that enable us to live together with some degree of mutual concern and intent. It is out of our impulse to know and doubt that arise our capacity and motivation to address questions about the nature of human life and existence, and to develop a world view or weltanschauung (e.g., Dilthey [Kluback & Weinbaum, 1957]; Kearney, 1984; Richards & Bergin, 1997).

Cultural variations in worldviews have long been a topic of interest (see Kearney, 1984). The social anthropologist, Bronislaw Malinowski (1922), wrote:

What interests me really in the study of the native is his outlook on things, his Weltanschauung, the breath of life and reality that breathes and by which he lives. Every human culture gives its members a definite vision of the world, a definite zest of life. In the roaming over human history, and over the surface of the earth, it is the possibility of seeing life and the world from the various angles, peculiar to each culture, that has always charmed me most, and inspired me with real desire to penetrate other cultures, to understand other types of life (Kearney, 1984, p. 37)

Richards and Bergin (1997) note that our world view — our weltanschauung — is about the nature of reality and our existence:

For example, how did the universe and the Earth come to exist? How did life, particularly human life, come to exist? Is there a Supreme Being or creator? What is the purpose of life? How should people live their lives in order to find happiness, peace, and wisdom? What is good, moral, and ethical? What is undesirable, evil, and immoral? How do people live with the realities of suffering, grief, pain, and death? Is there a life after death, and if so, what is the nature of the afterlife? (Richards & Bergin, 1997, p. 50)

Kearney (1984), who wrote a popular text on the topic of worldviews, states:

Worldview studies seek to discover, at much greater levels of abstraction, underlying assumptions about the nature of reality, assumptions that can then be stated by the anthropologist as formal propositions. The theoretical bias here is that these assumptions are systematically interrelated, and that they form a basis for culturally patterned decision making (influenced by values which also derive from these existential assumptions), and for other culturally specific cognitive activity. (Kearney, 1984, p. 36)

Both implicitly and explicitly, the thoughts of great religious leaders reflect particular worldviews (e.g., Bahaullah, Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, Jina, Lao Tse, Moses, Muhammad, Nanak, Zoroaster). These world views emerged from the leader’s personal encounters with the mysteries of life and from the historical and cultural context of their lives. Much as we do today, these religious leaders struggled with the search for meaning: — “Who after all knows? Who here will declare from whence it arose, whence this world?

Meaning, Health, and Wellbeing

- Health and Wellbeing: D-Words

Typically, mental health professionals have used the presence or absence of symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, tension) as an index of human health and wellbeing. Diagnostic interviews and symptom checklists are often used to determine whether a person can be considered mentally “diseased” or “disordered.” But this approach is limited, for it often fails to address other “d” words that are important: distress, demoralization, disability, and deviancy — all of which can be present without symptom manifestations.

- S-Words

For present purposes, there are more important words than the “d” words. These words go beyond reductionistic biological and social levels to those levels of functioning concerning “meaning,” including: self, serenity, sanctuary, sacred, sanctified, soul, and spirituality. These words refer to different aspects of our functioning; they deal with our sense of being and purpose, they deal with our sense of relationship to the cosmos (e.g., Thoresen, 1998).

- Defining Health

Health, according to the World Health Organization (1975), is: “A state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (WHO, 1975, P. 17). I think WHO is correct in pursuing a “holistic” rather than “deficit” model; however, what is missing in the WHO definition is the spiritual dimension. This, too, is important, as noted previously. We can have struggles of the spirit. For Viktor Frankl, living without a sense of meaning, without meaningful values, spirituality, or responsibility results in a “noogenic neurosis,” a life characterized by aimlessness, purposelessness, and meaninglessness.

- Disorders of Meaning-Seeking and Meaning-Making

When our efforts after meaning-making are thwarted or denied, and when we our efforts to engage doubt are halted or restrained, we are faced with life situations that may place our health and wellbeing in jeopardy. Meaning-seeking and meaning-making are essential. This is the process by which we order, prioritize, and prize our beliefs with respect to our culturally constructed realities. It is the process permiting us to assert: “This is meaningful! This is not meaningful! This is right! This is wrong! This is good! This is bad!

No matter what the formal source of our beliefs may be (i.e., religion, life-philosophy, ideology), without meaning-seeking and meaning-making, we are left devoid of guideposts for life’s journey. It seems to me many discomforts, disorders, and diseases of our time are related to an absence of meaning-seeking and meaning-making. At the individual level these include despair, angst, boredom, alienation, psychosis and suicide. At the cultural level these include cultural disintegration, societal decay, national collapse.

- Problems of Blind Belief

The quest for meaning can result in blind commitment to a belief system that demands unconditional acceptance. While this may bring a respite from pangs and perils of uncertainty, it cannot provide the basis for spiritual health and wellbeing. Belief must be combined with doubt to be meaningful! Doubt is an essential part of human growth and becoming. While the mind of the “true believer” (see Eric Hoffer, 1964) may find comfort in the certainty associated with uncontested belief, their closed mind will prevent them from evolving toward new levels of knowledge and possibility.

Total and complete adherence to “religious” systems often has proven useful in dealing with many psychological and social problems (e.g., alcoholism, substance abuse, criminal behavior); but, it needs to be appreciated as a temporary station rather than a final destination.

There is considerable research (see Richards & Bergin, 1997; Taggart, 1994; Thoresen, 1998) suggesting human health is better and happiness is greater among those individuals who have meaningful belief systems regardless of whether the system is a formal religious system or an anti-religious system. But, unless doubt is present and the relativity of beliefs is acknowledged, we will remain in a static state, rather than a state of becoming. To have meaningful outcome in the quest for meaning, a continual dialogical interaction between belief and doubt must occur.

For meaningful meaning-making to occur, beliefs must be doubted and accepted, and then doubted again, in an endless cycle of inquiry, reflection, and contemplation. This, I think, is a life of the spirit; this is a life honoring spirituality.

- Pursuing Meaning in Therapy

While the present paper is not the forum for a detailed discussion of the need to include meaning-related matters within the therapeutic encounter, it is clear to me that therapists must increasingly address this topic. Some therapies (e.g., Existential Therapy, Logotherapy) are specifically concerned with the patient’s quest for meaning and make it the focus of the therapeutic encounter; for others, however, it is only incidental.

For many problems (e.g., depression, anxiety) and many groups (e.g., refugees, alcoholics), personal meaning is at the core of the difficulties they experience. It seems to me that having a sense of personal meaning is essential, and that mental health professions must do more to introduce it into assessment and therapy activities (see Wong & Fry, 1998).

Guideposts for a Spiritual Life

- The Ecology of the Spirit

There is an ecology of the spirit that can be understood and nurtured to assist us in our quest for meaning. Table 2 displays assumptions of the ecology of the spirit framework.

Thus, ultimately a sense of spirituality emerges from the joust between belief and doubt. Much as character is built through positive responses to adversity and life’s ordeals, evolving higher-order values and systems of meaning emerge from the dialectic between belief and doubt.

Erich Fromm (1947/1990) acknowledged the power and importance of doubt for meaning-making when he stated: “The quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning. Uncertainty is the very condition to impel man to unfold his powers.”

TABLE 3: ECOLOGY OF SPIRIT ASSUMPTIONS

- There is a real but chaotic world;

- Our sensate brain interacts (i.e., seeks, organizes, and assigns meaning) with information from this world and constructing smaller units of information into complex systems of ordered beliefs, helping to generate a broader sense of meaning;

- There is an effort after meaning: meaning making;

- This effort after meaning-making orders beliefs within a cultural context, resulting in a cultural-construction of reality;

- A sense of “mind” emerges from the “interaction” of the organism’s perceived meanings, and the demands/presses of the environmental milieu;

- This process generates a “conscious awareness” of the yielding an element: “self” or “person,” from the interactive forces;

- Beliefs, and belief systems, emerge from the interactive forces in response to the impulse and effort after meaning-making;

- Beliefs, and belief systems, are challenged by the inherent natural impulse to doubt.

- The continuous cycle of meaning-making emerging from the belief and doubt dynamic produces a sense of spirituality promoting salutogenic (health) consequences.

Thus, ultimately, a sense of spirituality emerges from the joust between belief and doubt. Much as character is built through positive responses to adversity and life’s ordeals, evolving higher-order values and systems of meaning emerge from the dialectic between belief and doubt.

Erich Fromm (1947/1990) acknowledged the power and importance of doubt for meaning-making when he stated: “The quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning. Uncertainty is the very condition to impel man to unfold his powers.”

The Experience of Spirituality

The term spirituality has so much “religious” overlay that it is frequently disregarded by many scientists and professionals as soon as it is used. My use of the term is unrelated to the traditional religious views of the term “spirit” as an immaterial substance associated with divine forces. For me, spirituality is a construct that can be used to explain certain behaviors characterized by a sense of wonder, awe, mystery, enhanced acuity, reverence, humility, and oneness or unity.

More than 50 years ago, Deikman (1966) noted certain states of consciousness result in the “discovery of mind,” including (1) feelings of intense realness; (2) unusual modes of perception; (3) feelings of being at one with something or someone (often described as an oceanic moment, aesthetic moment, mystical moment); (4) an inability to place the experience in words, (i.e., ineffable); and (5) an encounter in which all of these may occur simultaneously. These are qualities are also associated with spiritual experiences.

Spirituality emerges from our efforts after personal meaning-making. But, it is the interaction of belief and doubt that is the essential key to spirituality. As noted previously, the dialectic between belief and doubt encourages a willingness to explore and to push the boundaries of our perceptions and experiences to new limits. This, it seems to me, is the essence of spirituality, and this, it seems to me is the basis of good health and wellbeing.

Conclusions

This paper discussed a spectrum of connected topics related to the relationships of meaning, belief, doubt, meaning, mind, culture, spirituality, and wellbeing. The paper argues that human health and wellbeing involves spirituality. The discussion of these topics suggests the following conclusions were reached:

- The real world presents itself as chaotic array of stimuli to which the sensate brain responds by assigning order, coherence, and meaning; this is part of an inherent impulse to describe, understand, predict, and control the world about it.

- The brain builds upon the data that is sensed, stored, and managed to create higher order systems of beliefs that are imbued with personal and cultural meaning.

- Each belief system is rooted within a cultural context and is culturally constructed. This shapes the content of our beliefs and the process by which we seek to affirm, and to doubt them. Belief systems take the forms of worldviews, life-philosophies, religions, ideologies, and mythologies.

- Worldviews are concerned with essential existential questions of life including answers to questions about the nature of god(s), life after death, nature and the cosmos, human relations, and moral patterns of behavior — all of which are critical for our sense of personal meaning.

- Yet, even as we pursue meaning, in both its reflexive and conscious dimensions, we are challenged by the need to doubt the very belief systems we have constructed. It is through the dialectical process of belief and doubting that meaning-making assumes its most potent possibilities as spirituality.

- Doubt requires giving up the certainty, control, and sense of mastery that often accompanies commitment to a belief system. Yet, it is doubt that moves us to new possibilities and choices and doubt that affords us the chance to affirm old beliefs.

- Spirituality is a subjectively experienced sense of self that is accompanied by awe, reverence, mystery, tranquility, connection, and unity. The spiritual sense of self opens us to new levels of experience and new perceptions of meaning enabling us to develop and grow with an even greater sense of mastery and transcendence.

- Optimal health and wellbeing require this state of spirituality. Thus, it is crucial we reconsider previous notions about health and wellbeing associated with deficit models, and include spiritual health and wellbeing as required criteria for health. At the heart of spirituality, is doubt.

- To tolerate doubt, to accept doubt, to embrace doubt! This is the essential inherent impulse for guiding the inquiring mind . . . as always!

PLUS CA CHANGE, PLUS C’EST LA MEME CHOSE

(Jean Baptiste Alphonse Karr, 1849)

Endnotes:

- Marsella, A.J. (1999). In search of meaning: Thoughts on belief, doubt, and wellbeing. The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 18, 41-52.

- This is a revised version of a paper presented at the International Conference on Culture, Religion, and Health, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, September 21-22, 1998.

- This paper is dedicated to Professor Abe Arkoff (in memorial) and Professor Emeritus, Samuel Shapiro, both in the Department of Psychology, University of Hawai`i, Honolulu, Hawai`i, 96822.

Dedication offered in appreciation for their provocative and inspirational exchange of ideas over the years, and for their friendship, colleagueship, and mentoring, in the course of our mutual search for meaning.

References from 1999 publication paper remain, although some no longer cited in present paper:

Allport, G. (1950). The individual and his religion: A psychological interpretation. New York: Macmillan.

Allport, G. (1955). Becoming: Basic considerations for a psychology of personality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Brown, L. (Ed.) (1994). Religion, personality, and mental health. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Grosett & Putnam.

Deikman, AJ. (1966). Deautomatization and the mystic experience. Psychiatry, 29, 324-338.

Frankl, V. (1946/1959). Man’s search for meaning. New York: Pocket Books (originally published 1946).

Frankl, V. (1973). The doctor and the soul. New York: Vintage Press.

Fromm, E. (1947). Man for himself: An inquiry into the psychology of ethics. New York: Holt, Rinehardt, & Winston.

Hoffer, E. (1989). The true believer: Thoughts on the nature of mass movements. New York: Harper Collins (version published in 1968).

Kearney, M. (1984). World view. Novato, CA: Chandler & Sharp Publishers.

Kelly, G. (1956). The psychology of personal constructs. New York: Norton

Kierkegaard, S. (1849/1954). Fear and trembling and the sickness unto death. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday.

Klinger, E. (1998). The search for meaning in evolutionary perspective and its clinical implications. In P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.) The human quest for meaning (pp. 27-50). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kluback, W., & Weinbaum, M. (1957). Dilthey’s philosophy of existence: Introduction of Weltanschauugslehre. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Maddi, S. (1998). Creating meaning through making decisions. In P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.) The human quest for meaning (pp. 3-26). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Marsella, AJ., DeVos, G., & Hsu, F. (Eds.) (1985). Culture and self: Asian and western perspectives on self. London: Tavistock.

Marshall, L, & Magoun, H. (1998). Discoveries in the human brain. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press

Maslow, A. (1968). Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Maurer, W. (1986). Selections from the Rgveda. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

May, R. (1967). Psychology and the human dilemma. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Peirce, C. (1997). Essential Peirce: Selected philosophical writing 1893-1913 (Editor: Nathan Houser). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Richards, P., & Bergin, A. (1997). A spiritual strategy for counseling and psychotherapy. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association Press.

Sheinkin, D. (1986). Path of the kabbalah. New York: Paragon House.

Smith, N. (1993). Religions of Asia. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Smith, N. (1994). Religions of the West. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Taggart, S. (1994). Living as if. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Thoresen, C. (1998). Spirituality, health, and science: The coming revival. In S. Roemer, S. Kurpius, & C. Carmin (Eds.) The emerging role of counseling psychology in health care. New York: Norton.

Toynbee, A. (1968). Man’s concern with death. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Wong, P. (1998). Meaning-centered counseling. In P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.). The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 395-436). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wong, P., & Fry, P. (1998). The human quest for meaning. A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

World Health Organization (1975). Promoting health in the human environment. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Wulff, D. (1997). Psychology of religion: Classic and contemporary views. New York: Wiley.

___________________________________________

Anthony J. Marsella, Ph.D., a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment, is a past president of Psychologists for Social Responsibility, Emeritus Professor of psychology at the University of Hawaii’s Manoa Campus in Honolulu, Hawaii, and past director of the World Health Organization Psychiatric Research Center in Honolulu. He is known internationally as a pioneer figure in the study of culture and psychopathology who challenged the ethnocentrism and racial biases of many assumptions, theories, and practices in psychology and psychiatry. In more recent years, he has been writing and lecturing on peace and social justice. He has published 21 books and more than 300 articles, tech reports, and popular commentaries. His TMS articles may be accessed HERE and he can be reached at marsella@hawaii.edu.

Anthony J. Marsella, Ph.D., a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment, is a past president of Psychologists for Social Responsibility, Emeritus Professor of psychology at the University of Hawaii’s Manoa Campus in Honolulu, Hawaii, and past director of the World Health Organization Psychiatric Research Center in Honolulu. He is known internationally as a pioneer figure in the study of culture and psychopathology who challenged the ethnocentrism and racial biases of many assumptions, theories, and practices in psychology and psychiatry. In more recent years, he has been writing and lecturing on peace and social justice. He has published 21 books and more than 300 articles, tech reports, and popular commentaries. His TMS articles may be accessed HERE and he can be reached at marsella@hawaii.edu.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 24 Sep 2018.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: In Search of Meaning: Thoughts on Belief, Doubt and Wellbeing, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.