A Genocide Incited on Facebook, with Posts from Myanmar’s Military

ASIA-UPDATES ON MYANMAR ROHINGYA GENOCIDE, MILITARISM, MEDIA, 22 Oct 2018

Paul Mozur – The New York Times

A border police officer at a repatriation center for Rohingya returning to Myanmar. Human rights groups blame anti-Rohingya propaganda online for fueling violence and displacement.

Adam Dean for The New York Times

15 Oct 2018 — They posed as fans of pop stars and national heroes as they flooded Facebook with their hatred. One said Islam was a global threat to Buddhism. Another shared a false story about the rape of a Buddhist woman by a Muslim man.

The Facebook posts were not from everyday internet users. Instead, they were from Myanmar military personnel who turned the social network into a tool for ethnic cleansing, according to former military officials, researchers and civilian officials in the country.

Members of the Myanmar military were the prime operatives behind a systematic campaign on Facebook that stretched back half a decade and that targeted the country’s mostly Muslim Rohingya minority group, the people said. The military exploited Facebook’s wide reach in Myanmar, where it is so broadly used that many of the country’s 18 million internet users confuse the Silicon Valley social media platform with the internet. Human rights groups blame the anti-Rohingya propaganda for inciting murders, rapes and the largest forced human migration in recent history.

While Facebook took down the official accounts of senior Myanmar military leaders in August, the breadth and details of the propaganda campaign — which was hidden behind fake names and sham accounts — went undetected. The campaign, described by five people who asked for anonymity because they feared for their safety, included hundreds of military personnel who created troll accounts and news and celebrity pages on Facebook and then flooded them with incendiary comments and posts timed for peak viewership.

Working in shifts out of bases clustered in foothills near the capital, Naypyidaw, officers were also tasked with collecting intelligence on popular accounts and criticizing posts unfavorable to the military, the people said. So secretive were the operations that all but top leaders had to check their phones at the door.

Facebook confirmed many of the details about the shadowy, military-driven campaign. The company’s head of cybersecurity policy, Nathaniel Gleicher, said it had found “clear and deliberate attempts to covertly spread propaganda that were directly linked to the Myanmar military.”

On Monday, after questions from The New York Times, it said it had taken down a series of accounts that supposedly were focused on entertainment but were instead tied to the military. Those accounts had 1.3 million followers.

“We discovered that these seemingly independent entertainment, beauty and informational pages were linked to the Myanmar military,” the company said in its announcement.

The previously unreported actions by Myanmar’s military on Facebook are among the first examples of an authoritarian government’s using the social network against its own people. It is another facet of the disruptive disinformation campaigns that are unfolding on the site. In the past, state-backed Russians and Iranians spread divisive and inflammatory messages through Facebook to people in other countries. In the United States, some domestic groups have now adopted similar tactics ahead of the midterm elections.

Screen shots from the official account of the Myanmar military’s commander in chief, whose pages were taken down in August. Facebook

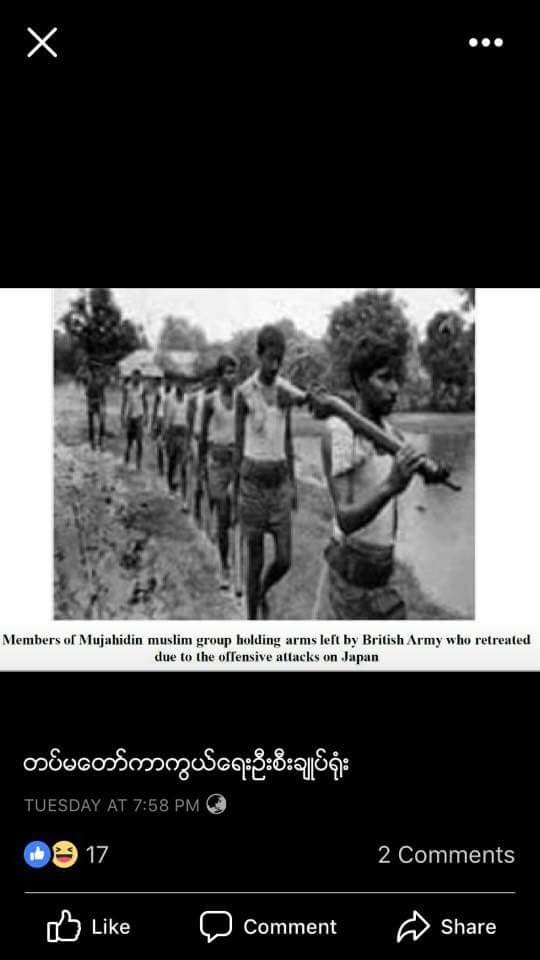

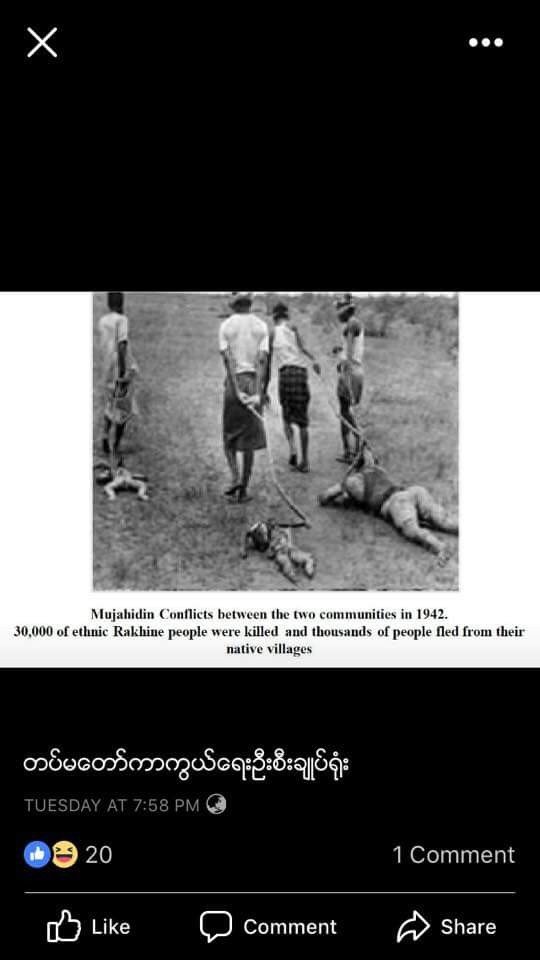

The photos claim to show evidence of conflict in Myanmar’s Rakhine State in the 1940s, but the images are from Bangladesh’s war for independence from Pakistan in 1971.

Facebook

“The military has gotten a lot of benefit from Facebook,” said Thet Swe Win, founder of Synergy, a group that focuses on fostering social harmony in Myanmar. “I wouldn’t say Facebook is directly involved in the ethnic cleansing, but there is a responsibility they had to take proper actions to avoid becoming an instigator of genocide.”

In August, after months of reports about anti-Rohingya propaganda on Facebook, the company acknowledged that it had been too slow to act in Myanmar. By then, more than 700,000 Rohingya had fled the country in a year, in what United Nations officials called “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” The company has said it is bolstering its efforts to stop such abuses.

“We have taken significant steps to remove this abuse and make it harder on Facebook,” Mr. Gleicher said. “Investigations into this type of activity are ongoing.”

The information committee of Myanmar’s military did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The Myanmar military’s Facebook operation began several years ago, said the people familiar with how it worked. The military threw major resources at the task, the people said, with as many as 700 people on it.

They began by setting up what appeared to be news pages and pages on Facebook that were devoted to Burmese pop stars, models and other celebrities, like a beauty queen with a penchant for parroting military propaganda. They then tended the pages to attract large numbers of followers, said the people. They took over one Facebook page devoted to a military sniper, Ohn Maung, who had won national acclaim after being wounded in battle. They also ran a popular blog, called Opposite Eyes, that had no outward ties to the military, the people said.

Those then became distribution channels for lurid photos, false news and inflammatory posts, often aimed at Myanmar’s Muslims, the people said. Troll accounts run by the military helped spread the content, shout down critics and fuel arguments between commenters to rile people up. Often, they posted sham photos of corpses that they said were evidence of Rohingya-perpetrated massacres, said one of the people.

Digital fingerprints showed that one major source of the Facebook content came from areas outside Naypyidaw, where the military keeps compounds, some of the people said.

Some military personnel on the effort suffered from low morale, said two of the people, in part because of the need to spread unfounded rumors about people like Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel laureate and Myanmar’s de facto civilian leader, to hurt their credibility. One hoax used a real photo of Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi in a wheelchair and paired it with false suggestions that she had gone to South Korea for Botox injections, the people said.

The Facebook page of the sniper, Mr. Ohn Maung, offers one example of the military’s tactics. It gained a large following because of his descriptions of the day-to-day life of a soldier. The account was ultimately taken over by a military team to pump out propaganda, such as posts portraying Rohingya as terrorists, said two of the people.

One of the most dangerous campaigns came in 2017, when the military’s intelligence arm spread rumors on Facebook to both Muslim and Buddhist groups that an attack from the other side was imminent, said two people. Making use of the anniversary of Sept. 11, 2001, it spread warnings on Facebook Messenger via widely followed accounts masquerading as news sites and celebrity fan pages that “jihad attacks” would be carried out. To Muslim groups it spread a separate message that nationalist Buddhist monks were organizing anti-Muslim protests.

A settlement for Rohingya arrivals in Thang Khali, Bangladesh. More than 700,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar in what United Nations officials have called “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Adam Dean for The New York Times

The purpose of the campaign, which set the country on edge, was to generate widespread feelings of vulnerability and fear that could be salved only by the military’s protection, said researchers who followed the tactics.

Facebook said it had found evidence that the messages were being intentionally spread by inauthentic accounts and took some down at the time. It did not investigate any link to the military at that point.

The military tapped its rich history of psychological warfare that it developed during the decades when Myanmar was controlled by a military junta, which gave up power in 2011. The goal then was to discredit radio broadcasts from the BBC and Voice of America. One veteran of that era said classes on advanced psychological warfare from 15 years ago taught a golden rule for false news: If one quarter of the content is true, that helps make the rest of it believable.

Some military personnel picked up techniques from Russia. Three people familiar with the situation said some officers had studied psychological warfare, hacking and other computer skills in Russia. Some would give lectures to pass along the information when they returned, one person said.

The Myanmar military’s links to Russia go back decades, but around 2000, it began sending large groups of officers to the country to study, said researchers. Soldiers stationed in Russia for training opened blogs and got into arguments with Burmese political exiles in places like Singapore.

The campaign in Myanmar looked similar to online influence campaigns from Russia, said Myat Thu, a researcher who studies false news and propaganda on Facebook. One technique involved fake accounts with few followers spewing venomous comments beneath posts and sharing misinformation posted by more popular accounts to help them spread rapidly.

Human rights groups focused on the Facebook page called Opposite Eyes, which began as a blog about a decade ago and then leapt to the social network. By then, the military was behind it, said two people. The blog provided a mix of military news, like hype about the purchase of new Russian fighter jets, and posts attacking ethnic minority groups like the Rohingya.

At times, according to Moe Htet Nay, an activist who kept tabs on it, the ties of the Opposite Eyes Facebook page to the military spilled into the open. Once, it wrote about a military victory in Myanmar’s Kachin State before the news became public. Below the post, a senior officer wrote that the information was not public and should be taken down. It was.

“It was very systematic,” said Mr. Moe Htet Nay, adding that other Facebook accounts reposted everything that the blog wrote, spreading its message further. Although Facebook has taken the page down, the hashtag #Oppositeyes still brings up anti-Rohingya posts.

Today, both Facebook and Myanmar’s civilian leaders said they were keenly aware of the power of the platform.

“Facebook in Myanmar? I don’t like it,” said Oo Hla Saw, a legislator. “It’s been dangerous and harmful for our democratic transition.”

__________________________________________________

Wai Moe contributed reporting from Yangon, Myanmar.

A version of this article appears in print on Oct. 16, 2018, on Page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: Genocide Across Myanmar, Incited on Facebook.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

ASIA-UPDATES ON MYANMAR ROHINGYA GENOCIDE:

- Myanmar’s War Has Forced Doctors and Nurses into Prostitution

- Six Years After Their Darkest Hour, the Rohingya Have Been Abandoned

- The International Community Must Stand Up to Myanmar’s Junta

MILITARISM:

- Think Tanks Fueling Endless War - Think Tanks or Stink Tanks?

- Dolphins in the Military

- US Has Given Israel $22 Billion in Military Aid since October 2023

MEDIA: