To Fix the Climate Crisis We Must Face Up to Our Imperial Past

ENVIRONMENT, IN FOCUS, JUSTICE, HEALTH, CIVIL SOCIETY, SEXUALITIES, 15 Oct 2018

Daniel Macmillen Voskoboynik | Open Democracy – TRANSCEND Media Service

It’s time to join the dots between our overlapping crises of – and shared solutions to – environmental degradation, damaged health, racial oppression and gender injustice.

‘The invading civilization[s] confused ecology with idolatry. Communion with nature was a sin worthy of punishment… Nature was a fierce beast that had to be tamed and punished so that it could work as a machine, placed at our service for ever and ever. Nature, which was eternal, owed us slavery’ (1)

– Eduardo Galeano

8 Oct 2018 –There are many ways to see colonialism. A breakneck rush for riches and power. A permanent pillage of life. A project to appropriate nature, to render it profitable and subservient to the needs of industry.

We can see colonialism as imposition, as the silencing of local knowledges, and erasure of the other. Colonialism as a triple violence: cultural violence through negation; economic violence through exploitation; and political violence through oppression (2).

Colonialism was not a monolithic process, but one of diverse expressions, stages and strategies. Commercial colonialism, centred around ports, differed from settlement colonialism. But its common factor is that colonialism took states to seek access to new lands, resources and labourers. Impelled by God, fortunes or fame, with almost limitless ambition, countries and companies scrambled to acquire control of land. New territories were seen as business enterprises. Local inhabitants were either obstacles to be removed or workforces to be subjugated.

The colonial-imperial era is fundamental to an understanding of how we have arrived here. As Eyal Weizman notes: ‘the current acceleration of climate change is not only an unintentional consequence of industrialization. The climate has always been a project for colonial powers, which have continually acted to engineer it’ (3).

What did colonialism seek? Wealth and power are the abstractions. But concretely it was commodities: metals, crops, minerals, and people. Political might, economic growth and industrialization required hinterlands to provide raw materials, food, energy supplies, labour and consumer demand. States sought expansion, appropriating territories and dominions. Between 1400 and 1917, the Russian empire expanded a thousandfold (4).

Gold and silver supplied the first vice, feverishly obsessing the early colonizers. From the 16th to the early 19th century, around 100 million kilograms of silver were hauled from the mines of Latin America to Europe. The Spanish writer Alonso de Morgado observed at the time that enough treasure had arrived on the shores of Seville by the 1580s to pave the entire city’s streets with gold and silver (5).

Plant commodities – from sugar to spices, cotton to coffee – would follow, as empires arranged the world to satisfy metropolitan tastes. Nature would serve as the canvas, the prize, and the victim of colonialist dreams (6).

The impact on nature

Nature narrates the colonial story, through its vast mines, its desecrated rivers, and emaciated territories. Across continents, mangroves, grasslands, rainforests, and wetlands were cleared to make way for quarries, plantations, ranches, roads and railways.

As historian Richard Drayton explains, imperialism – the expansion of empire – was ‘a campaign to extend an ecological regime: a way of living in Nature’ (7). Entire landscapes had to be subjected to control and exploitation. Overuse, pollution and deforestation were the norm.

Colonies were arranged to maximize and facilitate extraction. Profit was the compass. French colonial planners divided ‘useful Africa’ from ‘useless Africa’ (8). Lands were surveyed, zoned, parcelled, and mapped. All these endeavours relied on a narrative of emptiness, of nothingness.

The New World’s territories were vacant fields, lands of nobody, terra nullius – open for conquest and colonizing. The Arctic, the Outback, the Wild West and the Amazon were (and continue to be) enduring metaphors that allowed colonisers to depict territories as barren wastelands. But these lands were not empty. The fiction of negation, and discovery, was used to justify the clearance of native habitats and inhabitants.

Nature was a blank slate, to be reconfigured and rendered useful. Where colonizers arrived, maps were redrawn, inhabitants ousted, and new methods of production installed. Collective land management practices were shredded, as models of individual property ownership were imposed. New courts and laws governed the territory, handing lands over to concessionary companies and settlers. Long-term residents were now ‘squatters’ on their own land.

Time-tested and locally rooted agricultural traditions were trampled and stamped out (9). In Mexico, peasants were stripped of their milpa lands. In Madagascar, the tavy system was outlawed.

Rural areas were dragooned into ambitious imperial strategies, with villages forced to pay tribute or follow new production regimes. Local peasants were subjected to forced cultivation, compelled to grow what they were told. In French Equatorial Africa, the Mandja people were barred from hunting and pushed into work on cotton plantations (10). In 1905, communities living in the German-controlled Tanganyika (now part of Tanzania) revolted against policy forcing them to grow cotton for export. In response, as historian John Reader recalls: ‘three columns advanced through the region, pursuing a scorched earth policy – creating famine. People were forced from their homes, villages were burned to the ground; food crops that could not be taken way or given to loyal groups were destroyed’ (11). Around 300,000 people would perish.

From continent to continent, staples were replaced by cash crops. Plantation systems were installed, designed to maximize yields. In India, the British entirely reorganized the agricultural system. India’s land, previously used for low-scale subsistence agriculture, would now be destined for cash crops such as cotton and tea, grown for export to international markets. The Portuguese empire installed cotton regimes across its Brazilian, Angolan and Mozambican colonies.

Communal water management techniques were replaced with enormous works of engineering and state regulation (12). Pseudo-ecological arguments were often used to discredit local peoples and justify the clearance of communities. Traditional pastoralist practices were framed as outdated, damaging and ineffective. French July Monarchy propagandists used Arab desertification of Algerian land as a justification for conquest: once in control, France would restore ecological order and change the climate (13).

Perhaps the most destructive agrarian practice involved sugar. In the Canary and Cape Verde islands, sugar production was imposed through deforestation, woodlands were cleared to end up as deserts (14). The forested Atlantic island of Madeira, which means wood in Portuguese, was virtually stripped of trees to make way for livestock and sugarcane plantations. Slaves, transported from the Canary Islands and Africa, dug thousands of kilometres of canal to irrigate the sugarcane fields. Once Madeira’s forests were cleared, and the sugar industry could no longer burn wood to fuel its mills, plantations were replaced with vineyards (15).

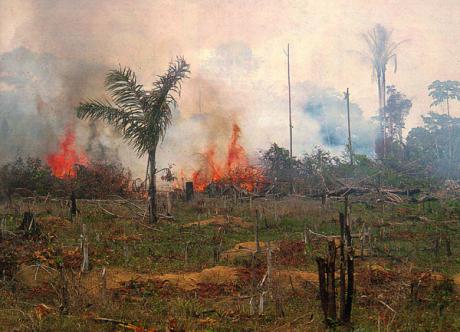

In the Americas, millions of hectares were stripped of forest life and burned to allow for massive cane plantations, accelerating soil erosion. In the West Indies and Guyana, rainforests were demolished to make way for sugarcane cultivation. Haiti, whose name means ‘green island’ in Arawak, was stripped of trees (16). In Mexico, deforestation exploded with the arrival of the Spanish, as forests were cleared to supply sugar refineries with fuelwood.

The logic of sugar’s monoculture was applied to a variety of commodities. The peripheries of the Amazon were cleared for coffee plantations. Using forced labour, Southeast Asia, southern Colombia and the Congo were deforested and converted into rubber plantations. Burma and Thailand saw their forests turned to mass ricefields, while Indian ecosystems were felled to make way cotton plantations.

In all these contexts, soils were exhausted and made sterile, degraded by deforestation and monoculture. In areas of Brazil and the Caribbean, the tree-bare terrains left by plantation economies became ideal incubators for mosquitos carrying malaria and yellow fever. Searing epidemics killed major segments of the population.

As historian Corey Ross recalls:

‘One of the recurring themes in the history of plantations is the perennial cycle of boom and bust. Whether the crop is sugar, tobacco, or cotton, the basic pattern is often the same: an initial frenzy of clearing and planting is followed by either a precipitous collapse of production or a gradual process of creeping decline before eventually ending in soil exhaustion, abandonment, and relocation elsewhere’ (17).

Since there was always more land to conquer and acquire, sustainability was irrelevant. The model was simple: exhaust the land, abandon it and clear new land. But the shortcomings of such short-termist thinking would become readily apparent, particular in the circumscribed territories in the Caribbean.

Beyond agriculture, intensive alluvial gold mining in the Caribbean, and silver mining in the Andes and Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains, devastated the local terrain. Trees were ripped out of the ground to fuel smelting furnaces, triggering erosion, flooding and major loss of soil fertility. Around the Bolivian mining city of Potosí, over 30 dams were built around Potosí to power its mills. But the hydraulic infrastructure installed to amplify production (as well as the local deforestation) caused constant flooding. In 1626, the major San Ildefonso dam broke; over 4,000 people were killed. Thousands of cubic tonnes of water contaminated by mercury effluent flooded into local rivers (18).

Loggers also wrought devastating impacts. India’s Malabar coast was cleared of teak forests by British merchants. Burma’s Tenasserim forest was raided next, stripped of teak over just two decades (19). Within only a handful of years, Fiji, Hawaii and the Marquesas Islands were cleared of sandalwood. In Canada, settlers set light to forests to provide a core ingredient of potash. In Australia, settlers predicted it would take centuries to clear the ‘Big Scrub’ terrain across New South Wales; it disappeared in just 20 years (20).

From territory to territory, life was swept away. Entire animal species were decimated through overhunting. The demand from European elites for fine furs drove hunters and trappers into Siberia and the Americas, carving open new frontiers. John Astor, founder of the American Fur Company, became the first multimillionaire in US history (21). Fishing fleets scoured the seas, slaughtering shoals. In less than 30 years, sea cows were harpooned into oblivion across the Bering Strait (22). Quaggas, thylacines, great auks, passenger pigeons, warrahs and hundreds of other species disappeared within decades. Industrial whaling, driven by demand for blubber, culled whales to the edge of extinction, removing all bowhead whales from the Beaufort Sea (23).

The impact on peoples

Just as environments and animal species needed to make way for productive ‘civilization’, so too did local inhabitants. The eradication and exploitation of nature was conjoined with the eradication and exploitation of peoples. Ecocide came hand in hand with ethnocide. The Guanches, Lucayas, Charrúa and Beothuk are just some of the many peoples massacred on the altar of lucre.

The methods were common: seize, dispossess, exclude, expel, extract, and extinguish. Martinican author Aimé Césaire would later note that between ‘colonizer and colonized there is room only for forced labor, intimidation, pressure, the police, taxation, theft, rape, compulsory crops, contempt, mistrust, arrogance, self-complacency, swinishness, brainless elites, degraded masses’ (24). The life of empire depended on the theft of life.

In the colonial realm, nature and those deemed inferior enough to be part of it, had to be removed or put to work. Governed by whips and watches, labourers were forced to work the earth: to slash, mine, break, cut, harvest, extract, carry and cart. Across its centuries, coerced labour found different incarnations, from formal slavery to convict-leasing, from indentured labour to peonage. Under systems of bondage, human beings were treated as chattel, expendable facets of the exploitation of expendable lands.

NOTES:

- Eduardo Galeano, ‘Mundo: Cuatro frases que hacen crecer la nariz de Pinocho’, Servindi, nin.tl/Galeano#

- Horacio Machado Aráoz, ‘El territorio moderno y la geografía (colonial) del capital’, Memoria y Sociedad, Vol 19, No 39, 2015; Vumbi-Yoka Mudimbe, The invention of Africa, Indiana University Press, 1988.

- Eyal Weizman and Fazal Sheikh (photographs), Colonization as Climate Change in the Negev Desert, Steidl, 2015.

- Susan Crate, ‘Viliui Sakha of Subartic Russia and Their Struggle for Environmental Justice’, Environmental justice and sustainability in the former Soviet Union, MIT Press, 2009, p 190.

- Kendall W Brown, A History of Mining in Latin America, University of New Mexico Press, 2012.

- This framing draws on the writings of Danilo Urrea and Tatiana Roa Avendaño on the role of nature in the Colombian peace process. See: ‘La cuestión ambiental’, Y sin embargo, se mueve, Ediciones Antropos, 2015.

- Richard Drayton, Nature’s Government, Yale University Press 2000, p 229.

- James Ferguson, Global Shadows, Duke University Press, 2006, p 39.

- David R Montgomery, Dirt: the erosion of civilizations, University of California Press, 2012, p 110.

- Michael Perelman, The Invention of Capitalism, Duke University Press, 2000, p 52.

- Robert H Nelson, ‘Environmental Colonialism: “Saving” Africa from Africans’, Independent Review, Vol 8, No 1, 2003.

- William M Adams, ‘Nature and the colonial mind’, in William M Adams & Martin Mulligan, eds, Decolonizing Nature, Earthscan, 2003, p 25.

- Diana Davis, Resurrecting the Granary of Rome, Ohio University Press, 2007, pp 4-6.

- Per Lindskog & Benoit Delaite, ‘Degrading land’, Environment and History, Vol 2, No 3, 1996.

- Jason W Moore, ‘Madeira, Sugar, and the Conquest of Nature in the “First” Sixteenth Century’, Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 2009.

- David R Montgomery, op cit, p 231.

- Corey Ross, ‘The plantation paradigm,’, Journal of Global History, Vol 9, No 1, 2014, p 49.

- A Gioda, C Serrano & A Forenza, ‘Dam collapses in the world’, La Houille Blanche, Vol 4, 2002; Jason W Moore, ‘Silver, ecology and the origins of the modern world, 1450-1640’, Rethinking Environmental History, Altamira Press, 2007, p 132.

- Clive Ponting, A New Green History of the World, Random House, 2007, p 189.

- William M Adams, op cit, p 30.

- John F Richards, The Unending Frontier, University of California Press, 2003, p 463.

- Callum Roberts, The Unnatural History of the Sea, Island Press, 2007.

- Andrew Stuhl, Unfreezing the Arctic, University of Chicago Press, 2016, p 7.

- Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, Monthly Review Press, 2000, p 42.

____________________________________

This is the first of two extracts from The Memory We Could Be, Daniel’s new book published this Autumn by New Internationalist Books.

Go to Original – opendemocracy.net

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

ENVIRONMENT:

- COP30’s Three F-Words: Failure on Fossil Fuels

- Declaration of the Peoples’ Summit Towards COP30

- Plutonium Found at Former San Francisco Naval Shipyard – Navy Faces Cover-Up Claims

IN FOCUS:

- Towards Piracy 2.0

- You Are Chosen if You Say You Are

- Manifestation of Inherent Human Elements in Creating Values for Sustainable Peace

JUSTICE:

- Int’l Court of Justice Finds Israelis Broke Law by Starving Palestinians of Gaza

- Gaza Tribunal: A Historic Statement in the Shadow of Testimony

- Bertrand Russell's Historic War Crimes Tribunal against the US in Vietnam, 1964-1967

HEALTH:

- FDA Orders COVID ‘Vaccine’ Makers Pfizer and Moderna to Warn Public about Heart Damage Risk

- U.S. Terminates Funding for Polio, H.I.V., Malaria and Nutrition Programs Around the World

- Autism, Made in the USA

CIVIL SOCIETY:

- Fragmented Society

- Get Out of My Face! Facial Recognition Technology Could Enslave Humankind like Never Before

- Privatization Increases Corruption

SEXUALITIES: