How Freud Made Clear We’re ‘Nothing but a Band of Murderers’

IN FOCUS, 3 Dec 2018

World War I, which ended exactly 100 years ago, bolstered Freud’s view that war doesn’t awaken violent impulses but rather tears off the thin veil of civilization and makes us confront the savage within.

9 Nov 2018 – At 11 A.M. on Monday, November 11, 1918, (the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month), the armistice marking the end of World War I was signed in a train car in France’s Compiègne Forest. It was the first war described as “the war to end all wars.” And at that moment, this seemed truly to be the case.

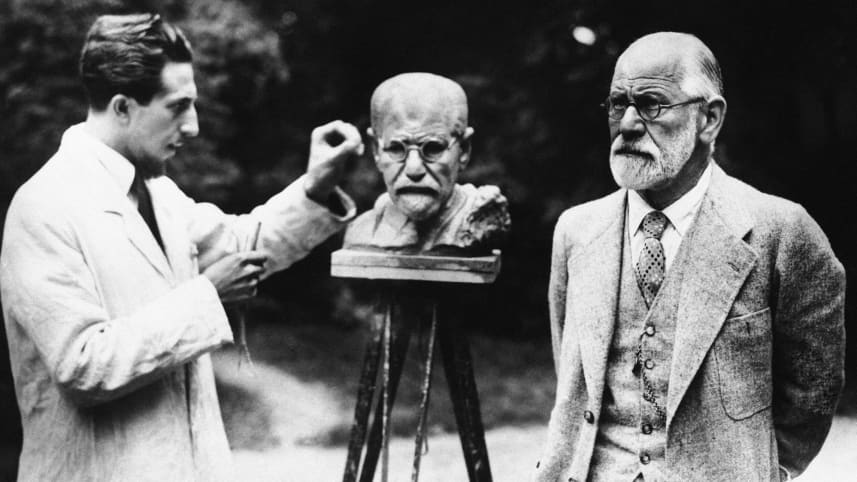

About 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) away, at 19 Berggasse in Vienna, sat a godless Jew with a bitter smile on his lips. Sigmund Freud had understood long before that all civilization was essentially a delicate piece of lacework, meticulously woven by generations upon generations in a heartrending attempt to cover the deep dark abyss of the soul. Freud was criticized and ridiculed for methodically examining the tears in that fabric – dreams, jokes, slips of the tongue, sudden bursts of savagery. The Great War was a wide enough tear to confirm his insights.

During the war, Freud’s clinical practice dwindled. He also lost all his savings, which were linked to Austrian bonds, and barely managed to support his family. With more time on his hands, he devoted himself mainly to writing, often with fingers trembling from the cold in his unheated study. Among his writings during this period were two essays about the war. Though largely forgotten, they still pack quite a punch.

In the essay “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death: The Disillusionment of the War,” written six months after the fighting began, Freud uncharacteristically expressed feelings of confusion, helplessness and an inability to understand the events of the day. At age 58 when the war broke out, Freud had lived through a remarkably long period of peace in Europe. In the era of “the first global village” in the early 20th century, citizens of Western countries could move from one country to another or spontaneously travel to other countries without prior arrangements or special documentation. Thus, according to Freud, a new Vaterland had arisen – one he viewed as akin to a vast museum comprising the beauty, art and history of all the nations.

But then the war, which no one including Freud believed possible, broke out. “We have told ourselves, no doubt, that wars can never cease so long as nations live under such widely differing conditions, so long as the value of individual life is so variously assessed among them, and so long as the animosities which divide them represent such powerful motive forces in the mind,” he wrote in his essay. But the war that was now occurring was between countries that shared a similar culture and way of life, between people of the same race, he lamented.

“We had expected the great world-dominating nations of white race upon whom the leadership of the human species has fallen, who were known to have world-wide interests as their concern, to whose creative powers were due not only our technical advances toward the control of nature but the artistic and scientific standards of civilization – we had expected these people to succeed in discovering another way of settling misunderstandings and conflicts of interest,” he wrote.

Not only were members of the white race killing one another, they were doing so with unprecedented diligence and success. Even science, which Freud as an enlightened and liberal person placed his hopes on, deeply disappointed him. All scientists did was search for more and more effective weapons. In a letter to psychoanalyst Lou Andreas-Salomé during that time, Freud wrote: “I have no doubt that humanity will get over this war too, but I know for certain that I and my contemporaries will see the world cheerful no more. It is too vile” (quoted in Peter Gay’s book, “Freud: A Life for our Time,” p. 253).

Humans were never that great

Freud was profoundly saddened, but not surprised. After all, what the war seemed to have destroyed was merely an illusion. Our species didn’t sink as low as we had feared, Freud consoled his readers and himself, because it had never risen as high as we had thought.

We mistakenly thought human beings to be better and more moral than they really are, for the instincts of the other always remain hidden to us. Civilized society demands “good” behavior and doesn’t care whether the origin of this behavior is an authentic internalization of its values or just the fear of sanction from transgressing the accepted rules. The multitudes who adhere to society’s requirements don’t do so by nature. They’re subject to continual repression of the instinct, and the great tension this creates manifests itself in neuroses and pathologies.

Freud went on: “There is, however, another symptom in our fellow-citizens of the world which has perhaps astonished and shocked us no less than the descent from their ethical heights which has so greatly distressed us,” he wrote, referring to the “want of insight shown by the best intellects” in cooperating with the ruling powers.

For example, Thomas Mann wrote in 1914: “War! It was a cleansing, a release that we experienced, and an incredible sense of hope.” Stefan Zweig, who ultimately became a pacifist, also served the Austrian propaganda machine, and Rainer Maria Rilke wrote of the “remote, incredible War God.”

This phenomenon is easy to explain, Freud said. “Students of human nature and philosophers have long taught us that we are mistaken in regarding our intelligence as an independent force and in overlooking its dependence on emotional life,” he wrote. “Our intellect, they teach us, can function reliably only when it is removed from the influences of strong emotional impulses; otherwise it behaves merely as an instrument of the will and delivers the inference which the will requires.” Psychoanalysis shows that even the most brilliant person will act like an imbecile when wisdom collides with emotional resistance.

This barb, perhaps unwittingly, is also aimed at its shooter. When war was declared, Freud himself was gripped by patriotism. “For the first time in 30 years I feel myself an Austrian,” he said, and enthusiastically supported Austria’s hard-line position against Serbia.

Fighting for the fatherland

Freud’s children apparently absorbed some of this patriotism. His three sons, Martin, Oliver and Ernst, volunteered to serve even though they weren’t obligated to. They were sent to the front and were decorated. Their anxious father had a “prophetic dream” one night foreseeing his sons’ deaths, with Martin first (though all of them survived the war). Freud later found out that on that day Martin was wounded on the Russian front, a discovery that got the master studying telepathy.

Death’s permanent presence in his thoughts during the war led Freud to other spectacular and depressing conclusions about human nature, which he shared in a talk at the B’nai Brith lodge in Vienna on February 15, 1915. This lecture formed the basis of his essay “Our Attitude Towards Death,” in which he argued that our distant ancestors’ approach to death was characterized by inconsistency. Primitive man wasn’t at all troubled by the death of the stranger, which was perceived as an event of no importance, nor did he hesitate to cause his death with much greater cruelty than exists in the natural world. The result of this stance can be seen in the history books, which are mainly composed of a series of killings.

The attitude to the death of people who are closely connected is more complex. When primitive man saw someone close to him being killed, his very being objected. But the law of emotional ambivalence, which to this day controls our relationships with the people we love most, inserted a drop of contentment even regarding the death of a loved one. Love and hate always appear together, Freud wrote, for love is a response to the hostile impulses that we feel even toward someone close and dear to us, because even the closest person is still always a stranger.

The emotional conflict regarding the death of loved ones is what gave rise to psychology and religion, Freud said. Over the grave of the loved one arose the doctrines of the soul and the belief in immortality, and that’s where the guilt feelings arose that spawned the first moral imperatives. The most important prohibition generated by the awakening conscience was “Thou Shalt Not Kill.” It was conceived from the outset as a response to the hidden hatred behind the mourning for loved ones who have died, and later expanded to be directed at strangers and eventually enemies too.

“Such a powerful inhibition can only be directed against an equally strong impulse,” Freud wrote. “What no human being desires to do does not have to be forbidden, it is self-exclusive. The very emphasis of the commandment: Thou shalt not kill, makes it certain that we are descended from an endlessly long chain of generations of murderers, whose love of murder was in their blood as it is perhaps also in ours.”

Just like primitive man, he added, “in our unconscious we daily and hourly do away with all those who stand in our way, all those who have insulted or harmed us.” Our unconscious will also kill over trivial matters – it’s the only punishment it can mete out. To judge by our unconscious impulses, we are “nothing but a band of murderers”; the only thing that has changed is our cultural and normative attitude toward death. War does not awaken violent impulses, it “strips off the later deposits of civilization and allows the primitive man in us to reappear.”

War cannot be abolished, Freud concluded. We must therefore recognize that in our civilized attitude toward death we are ignoring reality.

“Were it not better to give death the place to which it is entitled both in reality and in our thoughts and to reveal a little more of our unconscious attitude towards death which up to now we have so carefully suppressed?” he asked. While it may seem a step backward, at least it takes the truth into account and so makes life more bearable, he argued, summing it up thus:

“We remember the old saying:

“Si vis pacem, para bellum.

“If you wish peace, prepare for war.

“The times call for a paraphrase:

“Si vis vitam, para mortem.

“If you wish life, prepare for death.”

_______________________________________________________

More:

- When Freud and Einstein tried to answer an age-old question: Why war?

- Freud’s secret fellowship of the ring

- Vienna is trying to get its Jews back – will it succeed, with the far right on the rise?

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.