Martin Luther King Jr. (15 Jan 1929 – 4 Apr 1968)

BIOGRAPHIES, 14 Jan 2019

Biography – TRANSCEND Media Service

Civil Rights Activist, Minister

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was a Baptist minister and social activist who led the Civil Rights Movement in the United States from the mid-1950s until his death by assassination in 1968.

Martin Luther King Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. King, both a Baptist minister and civil-rights activist, had a seismic impact on race relations in the United States, beginning in the mid-1950s. Among many efforts, King headed the SCLC. Through his activism, he played a pivotal role in ending the legal segregation of African-American citizens in the South and other areas of the nation, as well as the creation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. King received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, among several other honors. King was assassinated in April 4, 1968, and continues to be remembered as one of the most lauded African-American leaders in history, often referenced by his 1963 speech, “I Have a Dream.”

Early Years

Born as Michael King Jr. on January 15, 1929, Martin Luther King Jr. was the middle child of Michael King Sr. and Alberta Williams King. The King and Williams families were rooted in rural Georgia. Martin Jr.’s grandfather, A.D. Williams, was a rural minister for years and then moved to Atlanta in 1893. He took over the small, struggling Ebenezer Baptist church with around 13 members and made it into a forceful congregation. He married Jennie Celeste Parks and they had one child that survived, Alberta. Michael King Sr. came from a sharecropper family in a poor farming community. He married Alberta in 1926 after an eight-year courtship. The newlyweds moved to A.D. Williams home in Atlanta.

Michael King Sr. stepped in as pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church upon the death of his father-in-law in 1931. He too became a successful minister, and adopted the name Martin Luther King Sr. in honor of the German Protestant religious leader Martin Luther. In due time, Michael Jr. would follow his father’s lead and adopt the name himself.

Young Martin had an older sister, Willie Christine, and a younger brother, Alfred Daniel Williams King. The King children grew up in a secure and loving environment. Martin Sr. was more the disciplinarian, while his wife’s gentleness easily balanced out the father’s more strict hand. Though they undoubtedly tried, Martin Jr.’s parents couldn’t shield him completely from racism. Martin Luther King Sr. fought against racial prejudice, not just because his race suffered, but because he considered racism and segregation to be an affront to God’s will. He strongly discouraged any sense of class superiority in his children which left a lasting impression on Martin Jr.

Growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, Martin Luther King Jr. entered public school at age 5. In May, 1936 he was baptized, but the event made little impression on him. In May, 1941, Martin was 12 years old when is grandmother, Jennie, died of a heart attack. The event was traumatic for Martin, more so because he was out watching a parade against his parents’ wishes when she died. Distraught at the news, young Martin jumped from a second story window at the family home, allegedly attempting suicide.

King attended Booker T. Washington High School, where he was said to be a precocious student. He skipped both the ninth and eleventh grades, and entered Morehouse College in Atlanta at age 15, in 1944. He was a popular student, especially with his female classmates, but an unmotivated student who floated though his first two years. Although his family was deeply involved in the church and worship, young Martin questioned religion in general and felt uncomfortable with overly emotional displays of religious worship. This discomfort continued through much of his adolescence, initially leading him to decide against entering the ministry, much to his father’s dismay. But in his junior year, Martin took a Bible class, renewed his faith and began to envision a career in the ministry. In the fall of his senior year, he told his father of his decision.

Education and Spiritual Growth

In 1948, Martin Luther King Jr. earned a sociology degree from Morehouse College and attended the liberal Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania. He thrived in all his studies, and was valedictorian of his class in 1951, and elected student body president. He also earned a fellowship for graduate study. But Martin also rebelled against his father’s more conservative influence by drinking beer and playing pool while at college. He became involved with a white woman and went through a difficult time before he could break off the affair.

During his last year in seminary, Martin Luther King Jr. came under the influence of theologian Reinhold Niebbuhr, a classmate of his father’s at Morehouse College. Niebbuhr became a mentor to Martin, challenging his liberal views of theology. Niebuhr was probably the single most important influence in Martin’s intellectual and spiritual development. After being accepted at several colleges for his doctoral study including Yale and Edinburgh in Scotland, King enrolled in Boston University.

During the work on this doctorate, Martin Luther King Jr. met Coretta Scott, an aspiring singer and musician, at the New England Conservatory school in Boston. They were married in June 1953 and had four children, Yolanda, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott and Bernice. In 1954, while still working on his dissertation, King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church of Montgomery, Alabama. He completed his Ph.D. and was award his degree in 1955. King was only 25 years old.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

On March 2, 1955, a 15-year-old girl refused to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery city bus in violation of local law. Claudette Colvin was arrested and taken to jail. At first, the local chapter of the NAACP felt they had an excellent test case to challenge Montgomery’s segregated bus policy. But then it was revealed that she was pregnant and civil rights leaders feared this would scandalize the deeply religious black community and make Colvin (and, thus the group’s efforts) less credible in the eyes of sympathetic whites.

On December 1, 1955, they got another chance to make their case. That evening, 42-year-old Rosa Parks boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus to go home from an exhausting day at work. She sat in the first row of the “colored” section in the middle of the bus. As the bus traveled its route, all the seats it the white section filled up, then several more white passengers boarded the bus. The bus driver noted that there were several white men standing and demanded that Parks and several other African Americans give up their seats. Three other African American passengers reluctantly gave up their places, but Parks remained seated. The driver asked her again to give up her seat and again she refused. Parks was arrested and booked for violating the Montgomery City Code. At her trial a week later, in a 30-minute hearing, Parks was found guilty and fined $10 and assessed $4 court fee.

On the night that Rosa Parks was arrested, E.D. Nixon, head of the local NAACP chapter met with Martin Luther King Jr. and other local civil rights leaders to plan a citywide bus boycott. King was elected to lead the boycott because he was young, well-trained with solid family connections and had professional standing. But he was also new to the community and had few enemies, so it was felt he would have strong credibility with the black community.

In his first speech as the group’s president, King declared, “We have no alternative but to protest. For many years we have shown an amazing patience. We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice.”

Martin Luther King Jr.’s fresh and skillful rhetoric put a new energy into the civil rights struggle in Alabama. The bus boycott would be 382 days of walking to work, harassment, violence and intimidation for the Montgomery’s African-American community. Both King’s and E.D. Nixon’s homes were attacked. But the African-American community also took legal action against the city ordinance arguing that it was unconstitutional based on the Supreme Court’s “separate is never equal” decision in Brown v. Board of Education. After being defeated in several lower court rulings and suffering large financial losses, the city of Montgomery lifted the law mandating segregated public transportation.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference

Flush with victory, African-American civil rights leaders recognized the need for a national organization to help coordinate their efforts. In January 1957, Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and 60 ministers and civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches. They would help conduct non-violent protests to promote civil rights reform. King’s participation in the organization gave him a base of operation throughout the South, as well as a national platform. The organization felt the best place to start to give African Americans a voice was to enfranchise them in the voting process. In February 1958, the SCLC sponsored more than 20 mass meetings in key southern cities to register black voters in the South. King met with religious and civil rights leaders and lectured all over the country on race-related issues.

In 1959, with the help of the American Friends Service Committee, and inspired by Gandhi’s success with non-violent activism, Martin Luther King visited Gandhi’s birthplace in India. The trip affected him in a deeply profound way, increasing his commitment to America’s civil rights struggle. African-American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, who had studied Gandhi’s teachings, became one of King’s associates and counseled him to dedicate himself to the principles of non-violence. Rustin served as King’s mentor and advisor throughout his early activism and was the main organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. But Rustin was also a controversial figure at the time, being a homosexual with alleged ties to the Communist Party, USA. Though his counsel was invaluable to King, many of his other supporters urged him to distance himself from Rustin.

In February 1960, a group of African-American students began what became known as the “sit-in” movement in Greensboro, North Carolina. The students would sit at racially segregated lunch counters in the city’s stores. When asked to leave or sit in the colored section, they just remained seated, subjecting themselves to verbal and sometimes physical abuse. The movement quickly gained traction in several other cities. In April 1960, the SCLC held a conference at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina with local sit-in leaders. Martin Luther King Jr. encouraged students to continue to use nonviolent methods during their protests. Out of this meeting, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee formed and for a time, worked closely with the SCLC. By August of 1960, the sit-ins had been successful in ending segregation at lunch counters in 27 southern cities.

By 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. was gaining national notoriety. He returned to Atlanta to become co-pastor with his father at Ebenezer Baptist Church, but also continued his civil rights efforts. On October 19, 1960, King and 75 students entered a local department store and requested lunch-counter service but were denied. When they refused to leave the counter area, King and 36 others were arrested. Realizing the incident would hurt the city’s reputation, Atlanta’s mayor negotiated a truce and charges were eventually dropped. But soon after, King was imprisoned for violating his probation on a traffic conviction. The news of his imprisonment entered the 1960 presidential campaign, when candidate John F. Kennedy made a phone call to Coretta Scott King. Kennedy expressed his concern for King’s harsh treatment for the traffic ticket and political pressure was quickly set in motion. King was soon released.

‘I Have a Dream’

In the spring of 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. organized a demonstration in downtown Birmingham, Alabama. Entire families attended. City police turned dogs and fire hoses on demonstrators. Martin Luther King was jailed along with large numbers of his supporters, but the event drew nationwide attention. However, King was personally criticized by black and white clergy alike for taking risks and endangering the children who attended the demonstration. From the jail in Birmingham, King eloquently spelled out his theory of non-violence: “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community, which has constantly refused to negotiate, is forced to confront the issue.”

By the end of the Birmingham campaign, Martin Luther King Jr. and his supporters were making plans for a massive demonstration on the nation’s capital composed of multiple organizations, all asking for peaceful change. On August 28, 1963, the historic March on Washington drew more than 200,000 people in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial. It was here that King made his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, emphasizing his belief that someday all men could be brothers.

“I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

— Martin Luther King, Jr. / “I Have a Dream” speech, August 28, 1963

The rising tide of civil rights agitation produced a strong effect on public opinion. Many people in cities not experiencing racial tension began to question the nation’s Jim Crow laws and the near century second class treatment of African-American citizens. This resulted in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 authorizing the federal government to enforce desegregation of public accommodations and outlawing discrimination in publicly owned facilities. This also led to Martin Luther King receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for 1964.

King’s struggle continued throughout the 1960s. Often, it seemed as though the pattern of progress was two steps forward and one step back. On March 7, 1965, a civil rights march, planned from Selma to Alabama’s capital in Montgomery, turned violent as police with nightsticks and tear gas met the demonstrators as they tried to cross the Edmond Pettus Bridge. King was not in the march, however the attack was televised showing horrifying images of marchers being bloodied and severely injured. Seventeen demonstrators were hospitalized leading to the naming the event “Bloody Sunday.” A second march was cancelled due to a restraining order to prevent the march from taking place. A third march was planned and this time King made sure he was on it. Not wanting to alienate southern judges by violating the restraining order, a different tact was taken. On March 9, 1965, a procession of 2,500 marchers, both black and white, set out once again to cross the Pettus Bridge and confronted barricades and state troopers. Instead of forcing a confrontation, King led his followers to kneel in prayer and they then turned back. The event caused King the loss of support among some younger African-American leaders, but it nonetheless aroused support for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

From late 1965 through 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. expanded his Civil Rights Movement into other larger American cities, including Chicago and Los Angeles. But he met with increasing criticism and public challenges from young black-power leaders. King’s patient, non-violent approach and appeal to white middle-class citizens alienated many black militants who considered his methods too weak and too late. In the eyes of the sharp-tongued, blue jean young urban black, King’s manner was irresponsibly passive and deemed non-effective. To address this criticism King began making a link between discrimination and poverty. He expanded his civil rights efforts to the Vietnam War. He felt that America’s involvement in Vietnam was politically untenable and the government’s conduct of the war discriminatory to the poor. He sought to broaden his base by forming a multi-race coalition to address economic and unemployment problems of all disadvantaged people.

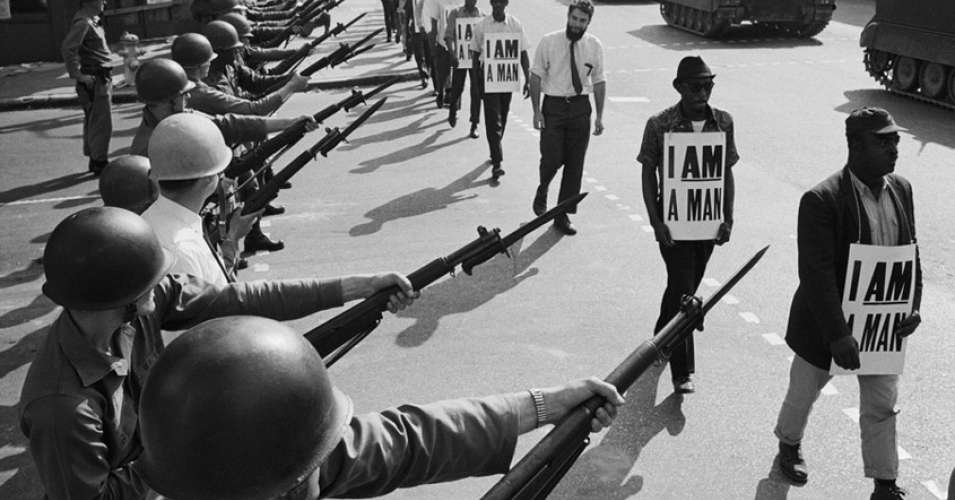

While Martin Luther King, Jr.’s name is most often attached to his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in history books, just before his assassination his fight for economic equality for black Americans was gaining steam; he spoke at a demonstration by sanitation workers in March 1968. (Photo: Recuerdos de Pandora/Flickr/cc)

Assassination and Legacy

By 1968, the years of demonstrations and confrontations were beginning to wear on Martin Luther King Jr. He had grown tired of marches, going to jail, and living under the constant threat of death. He was becoming discouraged at the slow progress civil rights in America and the increasing criticism from other African-American leaders. Plans were in the works for another march on Washington to revive his movement and bring attention to a widening range of issues. In the spring of 1968, a labor strike by Memphis sanitation workers drew King to one last crusade. On April 3, in what proved to be an eerily prophetic speech, he told supporters, “I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.” The next day, while standing on a balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Motel, Martin Luther King Jr. was struck by a sniper’s bullet. The shooter, a malcontent drifter and former convict named James Earl Ray, was eventually apprehended after a two-month, international manhunt. The killing sparked riots and demonstrations in more than 100 cities across the country. In 1969, Ray pleaded guilty to assassinating King and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. He died in prison on April 23, 1998.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s life had a seismic impact on race relations in the United States. Years after his death, he is the most widely known African-American leader of his era. His life and work have been honored with a national holiday, schools and public buildings named after him, and a memorial on Independence Mall in Washington, D.C. But his life remains controversial as well. In the 1970s, FBI files, released under the Freedom of Information Act, revealed that he was under government surveillance, and suggested his involvement in adulterous relationships and communist influences. Over the years, extensive archival studies have led to a more balanced and comprehensive assessment of his life, portraying him as a complex figure: flawed, fallible and limited in his control over the mass movements with which he was associated, yet a visionary leader who was deeply committed to achieving social justice through nonviolent means.

Go to Original – biography.com

Tags: Biography, Martin Luther King

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.