The Matrix 20 Years On: How a Sci-Fi Film Tackled Big Philosophical Questions

ARTS, 1 Apr 2019

Richard Colledge – The Conversation

Cult film The Matrix was released 20 years ago this month. From the Vedic Scriptures to Plato to Descartes to Kant to Baudrillard, the film explored philosophical dilemmas humanity wrestles with permanently.

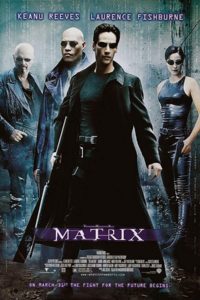

The Matrix was a box office hit, but it also explored some of western and eastern philosophies’ most interesting themes. HD Wallpapers Desktop/Warner Bros

27 Mar 2019 – Incredible as it may seem, the end of March marks 20 years since the release of the first film in the Matrix franchise directed by The Wachowski siblings. This “cyberpunk” sci-fi movie was a box office hit with its dystopian futuristic vision, distinctive fashion sense, and slick, innovative action sequences. But it was also a catalyst for popular discussion around some very big philosophical themes.

The film centres on a computer hacker, “Neo” (played by Keanu Reeves), who learns that his whole life has been lived within an elaborate, simulated reality. This computer-generated dream world was designed by an artificial intelligence of human creation, which industrially farms human bodies for energy while distracting them via a relatively pleasant parallel reality called the “matrix”.

‘Have you ever had a dream, Neo, that you were so sure was real?’

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vKQi3bBA1y8

This scenario recalls one of western philosophy’s most enduring thought experiments. In a famous passage from Plato’s Republic (ca 380 BCE), Plato has us imagine the human condition as being like a group of prisoners who have lived their lives underground and shackled, so that their experience of reality is limited to shadows projected onto their cave wall.

Read more: The great movie scenes: The Matrix and bullet-time

A freed prisoner, Plato suggests, would be startled to discover the truth about reality, and blinded by the brilliance of the sun. Should he return below, his companions would have no means to understand what he has experienced and surely think him mad. Leaving the captivity of ignorance is difficult.

In The Matrix, Neo is freed by rebel leader Morpheus (ironically, the name of the Greek God of sleep) by being awoken to real life for the first time. But unlike Plato’s prisoner, who discovers the “higher” reality beyond his cave, the world that awaits Neo is both desolate and horrifying.

Our fallible senses

The Matrix also trades on more recent philosophical questions famously posed by the 17th century Frenchman René Descartes, concerning our inability to be certain about the evidence of our senses, and our capacity to know anything definite about the world as it really is.

Descartes even noted the difficulty of being certain that human experience is not the result of either a dream or a malevolent systematic deception.

The latter scenario was updated in philosopher Hilary Putnam’s 1981 “brain in a vat” thought experiment, which imagines a scientist electrically manipulating a brain to induce sensations of normal life.

Read more: How do you know you’re not living in a computer simulation?

So ultimately, then, what is reality? The late 20th century French thinker Jean Baudrillard, whose book appears briefly (with an ironic touch) early in the film, wrote extensively on the ways in which contemporary mass society generates sophisticated imitations of reality that become so realistic they are mistaken for reality itself (like mistaking the map for the landscape, or the portrait for the person).

Of course, there is no need for a matrix-like AI conspiracy to achieve this. We see it now, perhaps even more intensely than 20 years ago, in the dominance of “reality TV” and curated identities of social media.

In some respects, the film appears to be reaching for a view close to that of the 18th century German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, who insisted that our senses do not simply copy the world; rather, reality conforms to the terms of our perception. We only ever experience the world as it is available through the partial spectrum of our senses.

The ethics of freedom

Ultimately, the Matrix trilogy proclaims that free individuals can change the future. But how should that freedom be exercised?

This dilemma is unfolded in the first film’s increasingly notorious red/blue pill scene, which raises the ethics of belief. Neo’s choice is to embrace either the “really real” (as exemplified by the red pill he is offered by Morpheus) or to return to his more normal “reality” (via the blue one).

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ManqKgHTGE

This quandary was captured in a 1974 thought experiment by American philosopher, Robert Nozick. Given an “experience machine” capable of providing whatever experiences we desire, in a way indistinguishable from “real” ones, should we stubbornly prefer the truth of reality? Or can we feel free to reside within comfortable illusion?

In The Matrix we see the rebels resolutely rejecting the comforts of the matrix, preferring grim reality. But we also see the rebel traitor Cypher (Joe Pantoliano) desperately seeking reinsertion into pleasant simulated reality. “Ignorance is bliss,” he affirms.

The film’s chief villain, Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving), darkly notes that unlike other mammals, (western) humanity insatiably consumes natural resources. The matrix, he suggests, is a “cure” for this human “contagion”.

We have heard much about the potential perils of AI, but perhaps there is something in Agent Smith’s accusation. In raising this tension, The Matrix still strikes a nerve – especially after 20 further years of insatiable consumption.

_________________________________________

Richard Colledge – Senior Lecturer & Head of School of Philosophy, Australian Catholic University

Richard Colledge – Senior Lecturer & Head of School of Philosophy, Australian Catholic University

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons license.

Go to Original – theconversation.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.