Rachel Carson on Writing and the Loneliness of Creative Work

INSPIRATIONAL, 6 May 2019

Maria Popova | Brain Pickings – TRANSCEND Media Service

“If you write what you yourself sincerely think and feel and are interested in… you will interest other people.”

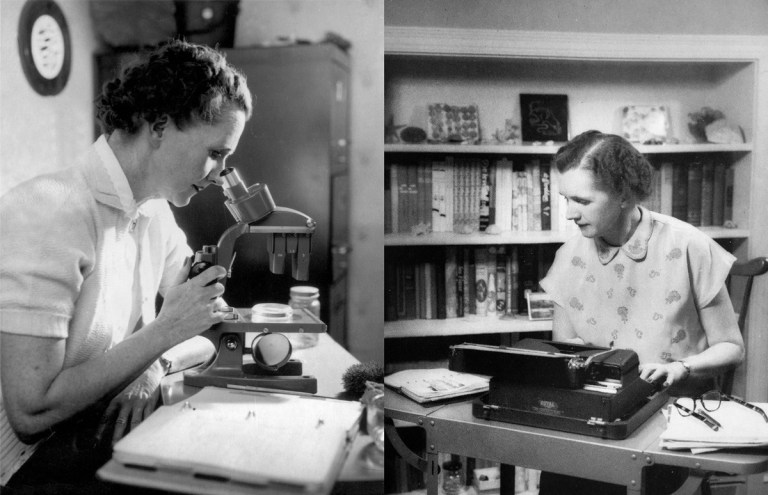

Many of the titans of literature have left, alongside a body of work that models powerful writing, abiding advice on the craft that examines the source of that power. Unrivaled among them in the combination of cultural impact and sheer splendor of prose is Rachel Carson (May 27, 1907–April 14, 1964) — the Promethean writer and marine biologist whose 1962 masterwork of moral courage, Silent Spring, ignited the modern environmental movement.

Many of the titans of literature have left, alongside a body of work that models powerful writing, abiding advice on the craft that examines the source of that power. Unrivaled among them in the combination of cultural impact and sheer splendor of prose is Rachel Carson (May 27, 1907–April 14, 1964) — the Promethean writer and marine biologist whose 1962 masterwork of moral courage, Silent Spring, ignited the modern environmental movement.

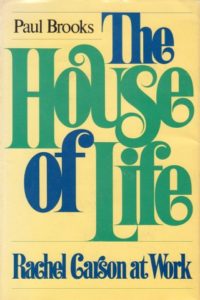

Nowhere does Carson’s writing philosophy, of which she never published a formal statement, come to life more vividly than in the 1972 out-of-print treasure The House of Life: Rachel Carson at Work (public library) — a portrait of Carson, drawn from her previously unpublished papers and letters, by Paul Brooks, who worked closely with her as editor-in-chief at Houghton Mifflin during the publication of The Edge of the Sea and Silent Spring.

A generation after Virginia Woolf contemplated the relationship between loneliness and creativity, Carson echoed the lament at the heart of Hemingway’s Nobel Prize speech and observed upon accepting one of the many writing awards she won:

Writing is a lonely occupation at best. Of course there are stimulating and even happy associations with friends and colleagues, but during the actual work of creation the writer cuts himself off from all others and confronts his subject alone. He* moves into a realm where he has never been before — perhaps where no one has ever been. It is a lonely place, even a little frightening.

In a sentiment that calls to mind choreographer Martha Graham’s notion of the “divine dissatisfaction” driving all creative work, Carson adds:

No writer can stand still. He continues to create or he perishes. Each task completed carries its own obligation to go on to something new.

Like Einstein, Carson made an unwearying effort to answer as much as she could of the voluminous fan mail she received, but her most touching correspondence is with a young aspiring writer by the name of Beverly Knecht — a blind girl hospitalized with what would turn out to be a terminal illness. After devouring The Edge of the Sea on Talking Books — an early audiobook program initiated by the Library of Congress and the American Foundation for the Blind in the 1930s — Beverly sent Carson a letter of affectionate appreciation. Carson wrote back:

I hope you can realize the very deep and lasting pleasure your letter gave me. In my writing, I have always tried not to lean on illustrations (of which most of my books have had few) but to create in words an image that would register clearly on the eyes of the mind. You make me feel I may have succeeded.

Illustration by Anne Herbauts from What Color Is the Wind?, a serenade to the senses inspired by a blind child

In a letter to another young woman with whom Carson felt a deep kinship of spirit, she returns to the subject of loneliness as a necessary condition for creative work:

You are wise enough to understand that being “a little lonely” is not a bad thing. A writer’s occupation is one of the loneliest in the world, even if the loneliness is only an inner solitude and isolation, for that he must have at times if he is to be truly creative. And so I believe only the person who knows and is not afraid of loneliness should aspire to be a writer. But there are also rewards that are rich and peculiarly satisfying.

More than anything, however, Carson held up work ethic and integrity of vision as the most vital requirements for being a successful writer. In a sentiment which James Baldwin would come to echo decades later in his thoughts on the relationship between talent and discipline, and which Hemingway had articulated in his advice on the art of revision, she tells her young correspondent:

Given the initial talent … writing is largely a matter of application and hard work, of writing and rewriting endlessly, until you are satisfied that you have said what you want to say as clearly and simply as possible. For me, that usually means many, many revisions.

Carson adds a thought that parallels my own animating ethos since the inception of Brain Pickings more than a decade ago:

If you write what you yourself sincerely think and feel and are interested in, the chances are very high that you will interest other people as well.

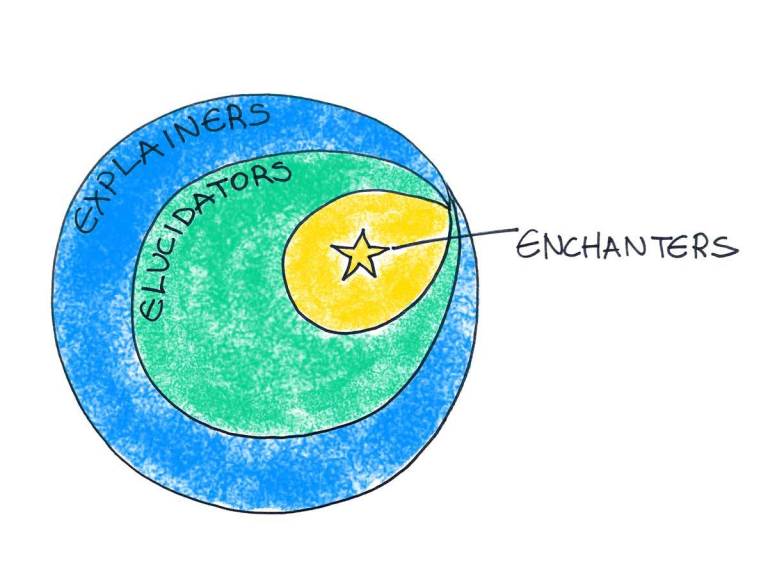

In previously contemplating what constitutes great nonfiction, I placed writers in a hierarchy of explainers, elucidators, and enchanters, the latter class being exceedingly rare and exceedingly rewarding to read. Carson was the twentieth century’s science-enchanter par excellence, whose writing was governed by her belief in “the magic combination of factual knowledge and deeply felt emotional response.” Today’s finest science writers — authors like Oliver Sacks, Janna Levin, Alan Lightman, Diane Ackerman, and James Gleick, who convey the inherent poetry of the universe in uncommonly enchanting prose — have some of Carson’s blood coursing through the pulse-beat of their books.

Carson, who made an art of illuminating nature beyond scientific fact, resented the notion that science is somehow separate from life. Our only means of upending the conventions and belief systems we resent is by modeling superior alternatives, and that is precisely what Carson did with her 1937 masterpiece Undersea, which pioneered a new way of writing about science with a strong lyrical sensibility, revealing the native poetry of nature. The piece became the seed for Carson’s 1951 bestseller The Sea Around Us, which won her the National Book Award. In her acceptance speech, she took head on the obtuse convention — one enduring to this day — that writing about science belongs in a special compartment of literature:

The materials of science are the materials of life itself. Science is part of the reality of living; it is the what, the how, and the why of everything in our experience. It is impossible to understand man without understanding his environment and the forces that have molded him physically and mentally.

The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history or fiction; it seems to me, then, that there can be no separate literature of science.

With an eye to the deliberate stylistic choices she made in how she wrote about the sea — choices highly unusual for their time, which steered nonfiction toward an epoch-making new aesthetic direction — she adds:

My own guiding purpose was to portray the subject of my sea profile with fidelity and understanding. All else was secondary. I did not stop to consider whether I was doing it scientifically or poetically; I was writing as the subject demanded.

The winds, the sea, and the moving tides are what they are. If there is wonder and beauty and majesty in them, science will discover these qualities. If they are not there, science cannot create them. If there is poetry in my book about the sea, it is not because I deliberately put it there, but because no one could write truthfully about the sea and leave out the poetry.

She took up the subject again in a letter written a few years after the publication of The Sea Around Us:

The writer must never attempt to impose himself upon his subject. He must not try to mold it according to what he believes his readers or editors want to read. His initial task is to come to know his subject intimately, to understand its every aspect, to let it fill his mind. Then at some turning point the subject takes command and the true act of creation begins… The discipline of the writer is to learn to be still and listen to what his subject has to tell him.

Later, during the writing of Silent Spring, Carson would reflect on the writer’s ultimate task:

The heart of it is something very complex, that has to do with ideas of destiny, and with an almost inexpressible feeling that I am merely an instrument through which something has happened — that I’ve had little to do with it myself.

She would then tell her beloved, Dorothy Freeman, in the same letter:

As for the loneliness — you can never fully know how much your love and companionship have eased that.

Lonely

Art by Isol from Daytime Visions

During her final revisions of Silent Spring, as she navigated the anguishing late stages of metastatic breast cancer, Carson addressed a friend’s concern that the book’s focus on pesticides would eclipse the splendor of the planet she was trying to protect. Acknowledging for the first and only time the dual motive power of moral outrage and fidelity to beauty that had animated her as she composed her masterpiece, she wrote:

I myself never thought the ugly facts would dominate, and I hope they don’t. The beauty of the living world I was trying to save has always been uppermost in my mind — that, and anger at the senseless, brutish things that were being done. I have felt bound by a solemn obligation to do what I could — if I didn’t at least try I could never again be happy in nature. But now I can believe I have at least helped a little. It would be unrealistic to believe that one book could bring a complete change.

Carson died eighteen months after Silent Spring was published and never lived to see herself proven wrong as it catalyzed the modern environmental movement by mobilizing the public conscience and effecting major government reform in environmental policy — nothing less than “a complete change” in culture and consciousness, proof that unrelenting idealism is in the end the mightiest realism.

*****

Complement the thoroughly wonderful The House of Life with Carson’s prescient protest against the government’s assault on science and nature and her almost unbearably touching farewell to her beloved, then revisit other timeless advice on writing from Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Susan Sontag, James Baldwin, Umberto Eco, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Ursula K. Le Guin.

UPDATE: For more on Carson, her epoch-making cultural contribution, and her unusual private life, she is the crowning figure in my book Figuring.

_______________________________________

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors. Email: brainpicker@brainpickings.org

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors. Email: brainpicker@brainpickings.org

Go to Original – brainpickings.org

Tags: Literature, Writting

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.