Road Map to a Green New Deal: From Extraction to Stewardship

ENERGY, ENVIRONMENT, PARADIGM CHANGES, SCIENCE, 29 Jul 2019

Mathew Lawrence | Common Wealth – TRANSCEND Media Service

5 Jul 2019 – The latest report from the UK-based think tank Common Wealth includes “a transatlantic proposal” for making public power ownership a core feature of the Green New Deal. A public buyout of the fossil fuel industry is the timeliest way to bring to heel the industry’s insatiable pursuit of profit at the expense of the planet.

Executive summary

Tinkering at the margins of an economic model driving environmental breakdown is guaranteed to deepen the climate emergency. To thrive, only a systemic response to a systems crisis will do. We need a UK Green New Deal to rapidly and justly decarbonise our society. This is a plan to restructure the economy toward sustainability, better steward and repair natural systems, hardwire democracy and justice into economic and social life, reimagine and expand prosperity, build resilience, and decolonise the global economy and its everyday operations. The goal is simple but transformative: a deep and purposeful reorganisation of our economy so that it is democratic, sustainable, and equal by design. Driven by a step change in public policy and investment, a UK Green New Deal can rescue our collective futures from climate catastrophe and create the conditions for universal human flourishing.

A UK Green New Deal will depend on an unprecedented mobilisation of finance, anchored by an ambitious expansion in public investment, and directed through a green industrial strategy to restructure the economy – both supply and demand – toward a post-carbon future. Given the annual cost of reaching net-zero by 2050 is estimated to be 1-2% of GDP to 20501, it is reasonable to assume achieving comprehensive decarbonisation at an earlier date will require increasing annual investment in decarbonising industries, technologies and infrastructures – perhaps up to a value of 3-5% of GDP per year in the next decade – creating millions of good jobs and building low-carbon wealth.

A UK Green New Deal, however will need to be more than a series of discrete policies to decarbonise. It must be a common project to transform society, extending freedom to all, and supporting new ways of living and working. The purpose is not just to decarbonise today’s economy but to build the democratic economy of tomorrow, one based on new and purposeful goals that centres what Tithi Bhattacharya describes as “life-making over profit-making”.2

Over the summer, Common Wealth is publishing a comprehensive road map for a Green New Deal for the UK. With contributions from leading climate activists, practitioners, policy experts, and academics, it will set out detailed plans for justly and rapidly decarbonising almost two dozen sectors or institutions in six main areas.

- Transforming and democratising finance to deliver a UK Green New Deal. At the core of the plan is the largest mobilisation of resources in peace-time history to finance transition. To deliver the volume and quality of investment needed will require reshaping private finance, repurposing central banking, creating a new architecture of international finance that can fund a global just transition, and delivering a transformative expansion in the scale and ambition of public investment to finance a UK Green New Deal.

- Restructuring the economy and work through a green industrial industrial strategy. An ambitious green industrial strategy shaped by workers and communities on the front line of change will be vital to driving a just transition, restructuring the economy to provide good work for all who want it. The road map includes sectoral strategies for transformation and new recommendations to ensure meaningful, well-rewarded work is at the heart of a UK Green New Deal.

- Building public affluence in place of private wealth. A UK Green New Deal will have to transform and move beyond the infrastructures and ways of life of the carbon age in little more than a decade, expanding social goods in place of private consumption. This will require reimagining how we provide and own housing, transport, and care. The road map will set out plans to democratise and decarbonise our energy system, retrofit and expand the UK’s building stock to provide decent, affordable and zero-carbon housing for all, scale a green public transport system, and support new forms of care.

- A decentralised and democratised state to drive decarbonisation: Delivering the UK Green New Deal will require a transformed state, with proposals for radical decentralisation to the nations, regions, cities and towns of the UK to support place-based decarbonisation, and new institutions to coordinate structural transformation.

- Nurturing a 21st century commons in place of extractivism: In place of an economics of extraction, a UK Green New Deal must nurture a dense and generative network of commons that encompases everything from better stewardship of nature to democratising digital technologies to plan and deliver decarbonisation. The road map will examine how to redistribute wealth and time to universalise security, support new ways of living and thriving, and expand leisure.

- Developing a green and just multilateralism: A Green New Deal must deliver climate justice, working to unpick the UK’s role in an extractive global economy, supporting reform of the architecture of international financial institutions, and promoting a global just transition through investment and technological transfers.

Our road map for a Green New Deal is based on the following principles:

- Our goal should be to decarbonise as rapidly and justly as feasibly possible based on a fair net-zero target. All aspects of public policy should be repurposed toward that goal, mobilising to decarbonise our economy substantially before 2050. We have both a responsibility and capacity to act, and rapid transition brings many co-benefits. Rather than pursuing a lowest-cost pathway to decarbonisation, we should seek the highest ambition route. The net-zero target should be based on low residual emissions offset by the restoring and scaling of natural carbon sinks in the UK, not via unproven technologies or offsetting through unfair land use in the Global South.

- Markets on their own cannot drive a society-wide reorganisation of production and consumption at the pace and scale required – a UK Green New Deal must be a government-led process of economic restructuring. A Green New Deal must be a government-led, society-wide mission to rapidly and justly restructure our economy toward environmental sustainability, decoupling economic activity from non-renewable resource consumption and carbon emissions while expanding the social and economic conditions needed for human flourishing. The means are a transformative step change in the forms and direction of investment, ownership, planning, and control in society, based on a deep institutional turn in the ordering of our economy toward democracy, sustainability and shared forms of sovereignty.

- A Green New Deal must deliver a just transition. A UK Green New Deal must create good forms of work for all who want it, be shaped by the voices and interests of communities on the frontline of change including social movements, workers and trade unions, and challenge inequalities of class, race, gender and generations at the heart of fossil fuel capitalism. A just transition means investing in communities and regions in the UK and globally where it is most needed to address historic and ongoing inequalities and prepare for the inevitable disruptions ahead.

- Climate crisis is a crisis of inequality. Both the causes and unequal effects of climate crisis are intimately linked to and driven by inequality. Stark, longstanding differences in consumption between countries and individuals are putting natural systems under intense stress. Yet despite not being responsible, the consequences of breakdown fall predominantly on poorer nations and households. A UK Green New Deal must challenge the inequalities driving climate emergency or risk deepening climate apartheid.

- A UK Green New Deal must support global climate justice. As a key nodal point in fossil fuel capitalism and a beneficiary of centuries of unequal extraction, the UK has a particular obligation to support a just global transition. Given the nature of climate crisis, effective action necessarily will involve effective international co-ordination. A UK Green New Deal will therefore have to be based on new forms of green internationalism, supporting the pooling of resources and technologies to address climate change equitably.

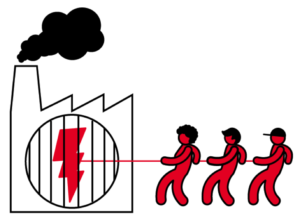

A UK Green New Deal will ultimately require rewiring an economy based on extraction where nature is commodified and unsustainably consumed, where the commons – natural, social, technological – is enclosed and its wealth privatised; and where value is extracted from labour, both waged and unwaged. Extraction drives the unequal accumulation of wealth and concentrates power.

An alternative must be anchored in models of ownership and control that are sustainable, democratic and purposeful by design to better steward our common resources. This will require a reimagining and expansion of common ownership to ensure we share in the wealth we create in common, new forms of stewardship to re-embed the economy in nature and end the false separation of the economic from the environmental, and a rewiring of control so we all have a stake and a say in decision-making that shapes our workplaces, communities, and society. And it will require a new purpose for the economy, focused on more social, creative and sustainable ways of creating, measuring and distributing value in the economy. A UK Green New Deal can build that future for all of us.

Over the coming weeks, Common Wealth will publish a set of detailed policy interventions that taken together can deliver on these principles and scale a democratic and sustainable economic architecture if powered by social movement, communities and politics organising for climate justice. A UK Green New Deal must be central to that transformation.

1. The climate crisis is political

The climate crisis is fundamentally a crisis of politics. We can therefore address it democratically and justly. We have the capability, ingenuity, and resources to radically and equitably decarbonise our economy and repair the natural systems we are currently ravaging. The challenge is in mobilising the democratic power and transformative programme to match the scale of emergency confronting us. If we fail, natural systems breakdown will accelerate further, with those least responsible for change bearing the brunt of its repercussions.

Climate breakdown is already here, it is just not evenly distributed. From extreme weather events to rising seas, from collapsing biodiversity and soil erosion, the effects are already devastating many communities, livelihoods, and ecosystems, particularly those in the Global South.3 Yet unless global carbon emissions are reduced by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero globally by 2050, temperature rises of 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels are highly likely within decades.4 This will mean large-scale planetary disaster and an end to the old assumptions – of climatic stability and benign nature – of political life.

Increases of 1.5 degrees or more would trigger accelerating and interconnected forms of natural systems breakdown that would all but guarantee immense and unnecessary suffering and disruption for many. Decarbonising rapidly enough to keep temperature rises to 1.5 degrees or less is therefore a question of life or death for many people and species and will require rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented transitions in economic and social systems to achieve.5 Yet on current trends, temperatures are forecast to increase by 3 to 5 degrees above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.6 Temperature rises on that scale will threaten the sustainability of human civilization as we know it and have devastating effects on health and mortality rates; it will condemn with certainty many of the habitats and species that coexist with and enrich us.7

Climate crisis and the distribution of its effects are laced through and driven by wider inequalities in the global economy, flowing from histories of colonial extraction. The poorest half of the world’s population are responsible for just 10% of carbon dioxide emissions compared to 50% for the richest tenth, yet developing countries will bear an estimated 75% of the costs of climate crisis.8 Similarly, driven by high levels of resource consumption by wealthier nations and individuals, we are dangerously outstripping the capacity of the Earth to regenerate itself, using materials and producing carbon faster than they can be regenerated or absorbed.9 Without change, we risk fatally eroding the biophysical conditions that sustain and renew life.

The uneven distribution of cause and effect of climate breakdown suggests we may have entered the Anthropocene geologically, our new era where human activity is the dominant and devastating influence on the climate and environment. Yet politically we live in the “capitalocene”: capitalism organises the relations between humans and the rest of nature in ways that are hierarchical, unequal, and extractive, appropriating and transforming nature and labour for private gain with little regard for the common wealth.10

The choice then is clear: we must rapidly and equitably transform the institutions, infrastructure, and ways of life of the carbon age in little more than a decade or face deepening climate apartheid.11 Transformation will require a daunting but ultimately deeply hopeful project of collective creation.

Out of crisis, we can build a better society that supports richer forms of human flourishing for all. But tinkering won’t suffice. Only a shared effort of reimagining, of new world making, can radically and justly decarbonise our society in ways that deepen and universalise individual and collective freedom.

Inaction or timidity guarantees escalating breakdown, and becomes more costly the longer we wait. A technocratic politics of anti-democratic managerialism – a climate Leviathan – risks securing decarbonisation at the expense of justice, amplifying the failures of an economic system that is driving climate breakdown.12 Or, worse, an ethno-nationalist vision of climate eschatology could triumph: a dangerous mix of a reckless defence of the commanding heights of the carbon economy rather than a justly managed transition, an aggressive acceleration of the inequalities of global capitalism, and the increasingly violent policing of people displaced by environmental crisis. Given this, a politics of incrementalism is not simply complacent, it is actively dangerous.

A “hothouse earth” of deep inequality, disruption and hollowed-out democracy does not have to be our future.13 We are not passive bystanders. But we are the last generation that can avert potentially runaway climate breakdown and build the forms of resilience we need to cope equitably with the inevitable change to come. The window to act is narrowing and action must be matched with scale and ambition. Only a Green New Deal can deliver this, rescuing our collective futures from its current trajectory. In the face of climate crisis, there really is no alternative.

2. A UK Green New Deal is the answer

A Green New Deal is a public-led, society-wide mission, shaped by workers, unions and communities, to rapidly and justly decarbonise the economy as fast as feasibly and fairly possible, bring our environmental footprint within fair and sustainable limits, and expand the social and material conditions for universal human flourishing. It aims to rapidly and justly restructure the economy toward environmental sustainability, decoupling economic activity from non-renewable resource consumption and carbon emissions while expanding the sectors and activities that can build and share sustainable wealth. The means are a transformative step change in the forms and direction of investment, ownership, planning, and control in society, based on a deep institutional turn in the ordering of our economy toward democracy, sustainability and shared forms of sovereignty.

The scale and pace of change required will not happen if left to market-based “solutions”.14 Markets on their own are an inappropriate mechanism to drive society-wide reorganisation of production and consumption within a short timeframe, risk amplifying inequalities, and fail to account for environmental externalities that threaten our collective futures. Progressively designed carbon price policies that lower demand for carbon-intensive goods and services, incentivise transition to a zero carbon future, and punish polluters inside and outside of the UK have a role to play, but “are no substitute for the large-scale investment in sustainable industries, new technologies, and the transition toward zero-emissions infrastructure.”15 A Green New Deal will instead depend on public action – at multiple levels of the state – playing a fundamental role in re-defining the direction of development and coordinating economic activity, repurposing institutions, and reshaping supply and demand in the economy to meet social and environmental needs.16

A Green New Deal must have justice and democracy at its heart. Economic restructuring must involve a double-movement, delivering comprehensive decarbonisation while transforming how the economy operates and for whom. In other words, the point is not just to decarbonise, but in the process build a new one of expanded possibility and social wealth, a deep reconfiguration of the economy based on new ways of living, working, and thinking.

Today, our economic model is failing to generate sustainable, fairly shared prosperity, a failure rooted in long-standing flaws in our economy.17 The British state is too centralised, hoarding power in Whitehall and giving too little to the nations, regions, cities and towns of the UK. Too many are denied security and dignity by a decade of austerity and insecure work. And globally the UK contributes to climate crisis as a key nodal point and beneficiary of an extractive and unequal international economy.

A radical Green New Deal must address these failings, democratising and decentralising the state, giving new resources and powers to communities, rewiring the institutional arrangements and ownership structures of our economy, creating new forms of purpose, measurement and value to guide economic activity, and building new forms of security. It must support a new internationalism, multilateral in orientation, decarbonising and decolonising in action, working for and shaped by the Global South and undoing the colonial legacies that the UK continues to benefit from. A Green New Deal should be a collective and democratic project to reimagine public affluence, the commons, the household economy and the market for sustainable prosperity, focused on meeting the needs of human and non-human life, and centring the voices and interests of ordinary people and communities.

3. The contours of a Green New Deal

The need for a transformational shared project to drive a step change in emissions and sustainability is clear. There have been remarkable and unforeseen successes over the past few decades. The UK’s electricity system has recently gone a fortnight with no coal generation, part of a remarkable transformation in energy generation. Carbon emissions have declined by around 38% from 1990 levels, decarbonising faster than any other major industrialised economy, due primarily to de-coaling energy generation and expanding renewables alongside shifts in industry18 (although importantly this figure fails to account for the emissions from imported goods based on consumption which substantially reduces the scale of emissions reduction18). Critically, public policy played a vital role in driving these shifts; emissions would have been twice as large today compared to 1990 in a “business as usual” scenario.19

Yet despite these successes, we are straining at the limits of what the current policy environment can achieve and are still failing to keep pace with our decarbonisation commitments. As the Committee on Climate Change noted in February 2019, the government is falling short in 15 out of 18 areas needed to meet its legally-binding climate targets. This is often due to unsupportive policy decisions.21 From the selling off of the Green Investment Bank to a company that supports open coal mines and fracking to backing for carbon-intensive infrastructures to inadequate support for home retrofitting and the renewables sector, many opportunities have been missed. As a result, the UK is on course to miss its carbon budgets in the 2020s and beyond by growing margins. Indeed, despite legislating for net-zero by mid-century, the UK is currently set to miss its target of an 80% reduction on 1990 levels of emissions by 2050.

A Green New Deal must consequently deliver a step change in outcomes, reducing carbon emissions across the whole of society at once, including where decarbonisation has been slowest and most difficult. This means that alongside driving forward areas where more rapid progress has already been achieved, such as in scaling low-carbon energy generation, credible strategies for just decarbonisation of sectors that have lagged behind must be at the centre a Green New Deal. This includes areas such as transport, land use, building stock, industry, heating, aviation, and shipping. A Green New Deal must drive the accelerated deployment of low-carbon technologies and infrastructure at scale and the managed and just phasing out of carbon-heavy activities.

Transforming and decarbonising supply will not be enough though; a Green New Deal will need to reshape demand too. The UK cannot decarbonise rapidly without reshaping consumption, including scaling down meat and dairy consumption, carbon-intensive activities particularly associated with the wealthiest, and fairly managing and constraining demand for air travel. It will also require new approaches to complex consumer and industrial supply chains to limit the global environmental footprint of the UK. A Green New Deal must then grasp the nettle of shifting society’s choice architecture or it will not deliver the scale of reductions required. It will also require the collective provision of goods and services currently privatised, transforming the means consumption. Changing the choice architecture will generate benefits but will require political and social leadership.

Far-reaching changes are needed to deliver decarbonisation. A Green New Deal must drive comprehensive and simultaneous change across many sectors.

Sector-by-sector plan for decarbonisation:

TO CONTINUE READING THE REPORT Go to Original – common-wealth.co.uk

Tags: Activism, Capitalism, Climate Change, Conflict, Cooperatives, Development, Economics, Ecosystem, Environment, Global warming, Green New Deal, Paradigm change, Social justice, Solutions

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

ENERGY:

- China Opens World’s Largest Offshore Solar Power Facility

- Nuclear Industry Takes Control of NASA

- The Nuclear Energy Dilemma: Climate Savior or Existential Threat?

ENVIRONMENT:

PARADIGM CHANGES:

- How We Can Place the Wellbeing Economy at the Heart of Our Cities

- The Circular Economy: What Is It, Why Is It Important and How Can We Embrace It?

- Listen to the Poets

SCIENCE: