Meet the Activists Risking Prison to Film VR in Factory Farms

ANIMAL RIGHTS - VEGETARIANISM, 9 Dec 2019

Andy Greenberg | Wired – TRANSCEND Media Service

This animal liberation group actually wants to be put on trial. Their goal: force jurors to wear VR headsets and immerse them in the suffering of animals bound for slaughter.

5 Dec 2019 – Just before midnight somewhere in the western United States, a white pickup truck’s high beams light up a stretch of dark highway.

The driver slows as his three passengers peer through the cab’s front and rear windshields, looking for the headlights of any cars that might catch them in the act of trespassing.

“Let’s be prepared to jump.”

“You have your bag and walkies?”

“Stop here. Here, here, here.”

As the truck speeds off, the three figures scramble quietly off the highway shoulder and into a terrain of scrub brush and jagged gullies. For the next 15 minutes, they walk down an unlit dirt road in near total darkness; even the waning moon’s sliver of light is hidden behind clouds. But their noses tell them they’re in the right place. They’re engulfed in a smell that intensifies as they walk: a blend of barnyard animal, excrement, and decaying flesh. The silence is interrupted only by the crunch of their feet on the sand and then, after a few minutes, sporadic, far-off guttural animal bellowing. They’re approaching their destination, a massive industrial pig farm.

As the three near the facility’s long, low-slung barns arrayed behind giant, man-made lagoons of pig feces and blood, they spot the guardhouse. A TV seems to flicker inside, as it had on the three previous nights. To avoid the building, they leave the road, circling away from the shed through a dry riverbed, and approach the barns from the opposite side.

In the darkness, one of the three intruders switches on a pair of night vision goggles and scans for guards—it’s her turn to remain outside and serve as lookout. The other two pull on Tyvek suits and polyurethane boot covers and run toward the barns.

The team’s leader and smallest member worms through a hole in the enclosure and lifts a bolt on a door to let the other one in. Then the two activists, members of an animal liberation organization known as Direct Action Everywhere, or DxE, start their work: They pull out cameras and begin documenting the inside of the facility, a typical factory farm of the kind that produces the vast majority of the pork Americans eat.

On one side of the two intruders, stretching beyond the edges of their headlamps’ light, full-grown pigs are crammed eight to a cage; the enclosures are just large enough that the activists can see small patches of concrete floor between the animals. On the other side, sows—each at least as intelligent and emotionally sensitive as a dog—are locked individually into metal pens roughly the dimensions of their bodies. The animals in these so-called gestation crates appear not to be able to turn around or even take a step.

Ducking and running through a half-covered hallway between the barns, the two activists enter another barn where they find mothers that have just given birth inside those same crates. Tiny piglets covered in birth fluid and blood stumble around on the metal grate floors. Reaching into a pen, the group’s leader helps to free one squealing piglet whose foot is caught in the grate. Others lie dead in corners of the pens or in piles of feces. They return to one pen where, the night before, they freed a group of injured piglets caught under a cage door. Now they see no sign of those injured animals other than a bloodstain on the floor.

I see all of this—the crates, the dead piglets, the bloodstain. Not in person, which would have required me to break the same trespassing laws as the DxE activists, but in their raw video recordings, which they show me the next day as we sit around a dining table of their Airbnb in a nearby town, reviewing the footage while a vegan pizza grows cold in the center of the table.

One of the DxE trespassers shot the footage with a Sony A7 III camera; he also retrieved several tiny cameras, small enough to escape workers’ notice, which he’d hidden around the farm on an earlier intrusion. Another activist had carried a less standard piece of equipment: a $400, 360-degree camera mounted on the end of an extension arm, recording everything around it with a pair of fish-eye lenses for a stripped-down experience of virtual reality.

That crude VR capture is, of course, missing some of the horrors described to me: The squeals are dampened. The smell is absent—I’d only experience it firsthand when we drove near the farm the next day, so that they could film it from above with a quadcopter drone, while swarms of flies from the nearby pig sewage lagoons filled their truck.

But through their ultrawide-angle lenses, I can get a hint of what it’s like to be inside the facility. On one of the activists’ laptops, sitting on the table of the Airbnb, I use the trackpad to rotate my point of view down an endless corridor of the barn’s cages. I swing the perspective to the front, and then to the back. In each direction, rows of doomed animals stretch out, farther than I can see, into the darkness.

Direct Action Everywhere’s cofounder, a compact 38- year-old Taiwanese American man named Wayne Hsiung, describes the American meat industry as a kind of vast dystopian hoax.

“Animal suffering is something people intrinsically care about,” Hsiung says. Americans can’t stand to see an animal die onscreen in a TV show. They obsess over a dentist who kills a beloved lion on a hunting trip in Zimbabwe, and they lavish billions of pageviews on cute animal videos on social media. To keep that same public happily buying hot dogs requires nothing less than a Matrix-like system of mass delusion, he argues. “The fight against animal agriculture,” Hsiung says, “is the fight against misinformation.”

At our first meeting, Hsiung sits cross-legged on a bed in his home in a lush subdivision in Berkeley, California, a house he shares with a rotating cast of guests, currently around half a dozen activists and seven animals. Hsiung speaks a bit like a spiritual guru, albeit one with the accelerated patter and citation-filled arguments of a political podcast host. Before embarking on his second career as the leader of DxE’s guerrilla animal liberation group—a loose network of thousands of activists in chapters around the world—Hsiung spent years working as a lawyer and academic researching behavioral economics.

From that behavioral economist’s perspective, he still marvels at the social influence of the global meat industry, the soothing images of small farms and happy pastures that it puts on packages of bacon, he says, to obscure the reality: a collection of factories whose contribution to climate change rivals that of automobiles, where tens of billions of creatures live out their short lives in confined squalor, overseen by underpaid migrant workers performing dangerous, grueling labor. “That takes some next-level hacking,” Hsiung says. “To convince the public that these massive agribusiness concerns, which are inflicting horrible suffering on animals, that are huge assembly line productions—that this is good.”

Defeating that disinformation has become an “arms race,” Hsiung says, one that stretches back to Upton Sinclair’s 1906 meat industry exposé, The Jungle. For decades, factory farms and slaughterhouses have, for economic reasons as much as PR ones, been moving away from urban areas to remote rural ones, out of the public eye. The companies that run them have lobbied for “ag-gag” laws that criminalize dissemination of video and photos from within their walls. They’ve tightened security against groups like his that seek to break into their facilities and film surreptitiously—all while processing more animals through their feeding barns and slaughterhouses than ever before.

“The fight against animal agriculture,” Hsiung says, “is the fight against misinformation.”

At the same time, the animal rights movement has gained an arsenal of tools to fight what they see as the information blackout around the meat industry. “Drones, secret cameras, VR, social media,” Hsiung says. “Over the past few years there’s been an eruption in technology, and that’s leading to a cataclysmic battle.”

If that description of the conflict sounds hyperbolic, it’s perhaps because the stakes are particularly high for Hsiung himself: He faces up to 60 years in prison on charges—including burglary and theft of livestock—related to a series of animal extractions he’s carried out over the past two years. In three of those operations, in which he helped remove animals from pig and turkey farms in Utah and an egg farm in California, he and his fellow DxE activists filmed their operations with virtual reality cameras: custom-built stereoscopic depth-capturing rigs far larger and more sophisticated than the simple 360-degree camera footage the activists had shown me at their Airbnb.

Hsiung wasn’t caught in the act of those intrusions. He and several other DxE members were charged only after they published the virtual reality footage they’d captured, which included images of their unmasked faces. DxE carries out what the animal liberation movement calls “open rescue,” a practice dating back decades in which animal rights activists publicly reveal their actions and identities to claim moral high ground. In some cases, hundreds of DxE activists have marched into animal facilities together, in daylight, to take out animals in acts of mass protest, sometimes streaming their actions live on Facebook. Even the anonymous DxE activists I met the day after their midnight pig farm operation intended to eventually reveal themselves—they said they were just waiting for the most strategic moment to do so.

DxE rejects framing these actions as civil disobedience. Instead, the group points to statutes in common law and some US state laws that allow bystanders to trespass to stop animal cruelty or help an animal in a life-threatening situation. Someone who rescues a starving piglet from a factory farm, they say, is no different from someone who breaks a window to save a dog locked in a hot car—an argument that has yet to be tested in court as a defense for factory farm intrusions.

While DxE’s technological savvy has put it in the spotlight, the group’s radical tactics have also set it apart from other animal rights activists, as has its abolitionist view that no “humane certified” or “free-range” certifications represent an acceptable compromise. The agribusiness trade group WATT Global Media has written that DxE “could very well be the most dangerous animal rights organization out there.”

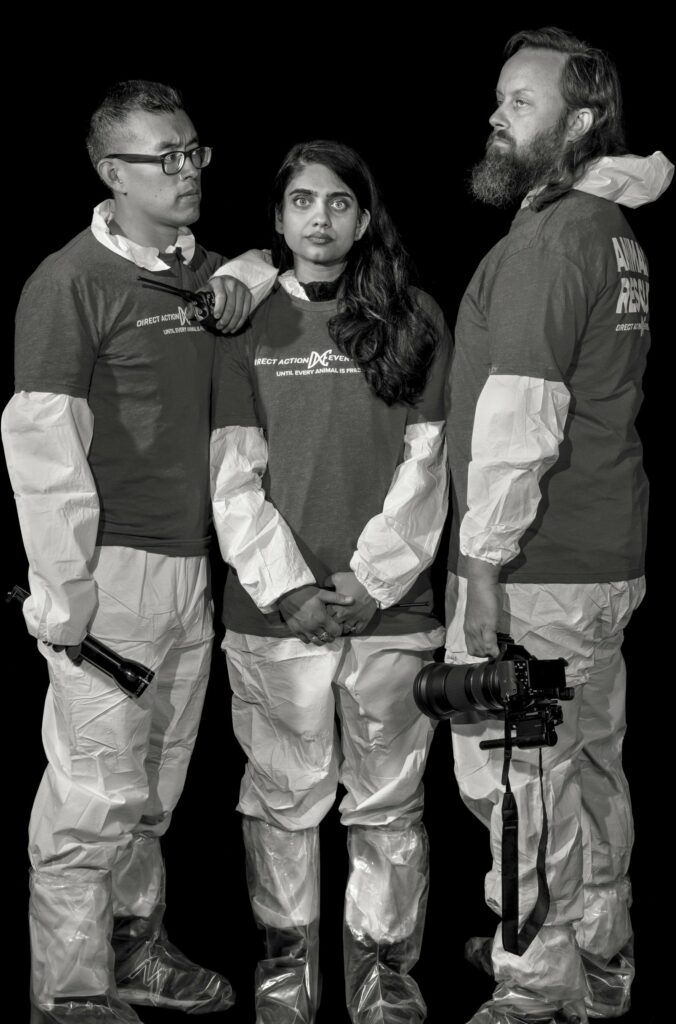

Hsiung with DxE members Priya Sawhney and Paul Darwin Picklesimer, outfitted as they would be for an intrusion into a factory farm.

Photograph: Philip Montgomery

Even some animal rights groups, while sympathetic to DxE’s views, set themselves apart from its absolutist approach—targeting ostensibly conscientious businesses like Whole Foods and Chipotle, along with the very worst animal rights offenders—and acknowledge that, in a world where meat consumption has increased for decades, an incrementalist approach may be more effective. “If people are going to continue to eat animal products, we have an obligation to reduce animals’ suffering,” says Andrew deCoriolis, executive director of Farm Forward, an animal rights group that advocates for smaller-scale, more humane animal farming. “If we can ensure that animals have lives worth living but preserve animals being raised for food, that would be much better than the track we’re currently on.” Other animal rights activists quietly believe that DxE’s approach of inviting criminal prosecution seems more likely to achieve martyrdom than real progress.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wlSE1X-hSqQ

But even as Hsiung’s charges mount, he’s never been more optimistic about the effects of his work. This spring, he and a codefendant, Paul Darwin Picklesimer, will face trial in Utah for breaking into Circle Four Farms, one of the world’s largest pig farms, and taking out two piglets. Both say they look forward to the proceedings as a rare opportunity. After years of open rescues that ended in dismissed charges, they believe the meat industry is finally ready for a direct confrontation, one that will allow them to put the industry itself on trial and broadcast the footage they’ve been collecting for years to a far larger audience.

In fact, they hope to use their trial to stage an unprecedented, Clockwork Orange–style stunt that will combine DxE’s legal and technological innovations: They plan to request that the jury—and perhaps the prosecutors and judge too—be required to strap on VR headsets and be immersed in the scenes the activists captured inside Circle Four. That footage, the activists point out, constitutes the central evidence against them. The jury’s reaction to it may determine whether they’re convicted as vandals and thieves or exonerated as rescuers of animals that DxE argues would otherwise have died and been discarded as trash.

Whether this radical legal tactic will fly in court may come down entirely to the discretion of a judge, who will have to decide whether the VR material’s relevance to the case outweighs its emotional impact, which could prejudice the jury against Circle Four. “The big question is whether they’ll be able to talk a judge into letting the VR stuff in,” says Hadar Aviram, a visiting fellow at Harvard Law School’s Animal Law and Policy Program who has focused her recent research on DxE. “The footage is quite arresting. I can see a jury, even in a rural county, a farming county, being very sympathetic to people trying to bring that to light.”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1tVeAwdoCzM

_________________________________________

Andy Greenberg (@a_greenberg) is a senior writer at WIRED and the author of the new book Sandworm: A New Era of Cyberwar and the Hunt for the Kremlin’s Most Dangerous Hackers.

This Article Appears in the January Issue

Tags: Activism, Animal Justice, Animal cruelty, Animal rights, Humanitarianism, Nonviolence, Solutions, Veganism, Vegetarianism, Violence

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

ANIMAL RIGHTS - VEGETARIANISM: