At Guantánamo Bay, Torture Apologists Take Refuge in Empty Code Words and Euphemisms

ANGLO AMERICA, 3 Feb 2020

Margot Williams – The Intercept

In this photo reviewed by U.S. military officials, the sun sets behind the closed Camp X-Ray detention facility on April 17, 2019, at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. Photo: Alex Brandon/AP

29 Jan 2020 – The accused were escorted into the courtroom by guards wearing gloves made of blue latex. The men were placed in seats one behind the other in five rows next to their lawyers. The sixth row was empty, but a chain was still attached for shackling a defendant to the floor.

Welcome to Guantánamo Bay, where an unused shackle is a small reminder of the abnormal fusing into the normal, nearly two decades after the first prisoners of the “war on terror” began arriving here. The defendants now are not chained, and they appear for court in clothing of their choice, often camouflage jackets or traditional garments worn in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, or Yemen; there are no more government-issued jumpsuits.

At the U.S. naval base that hosts the extraordinary military commissions for the prosecution of post-9/11 detainees, a view of the Sierra Maestra in the distance is one of the few reminders that you are in Cuba. There’s also a souvenir shop with trinkets that show sites in Havana you can’t drive or fly to from here. This is not that Cuba.

The U.S. military has attempted for years to devise a system for trying the men accused of organizing or aiding the terror attacks against America, but without giving them the benefit of a trial in federal court. This case has dragged on for almost eight years without a trial formally getting underway. There have been 40 pretrial hearings and extended arguments over what evidence can be introduced — and, for instance, whether the word “torture” can be used in relation to the interrogations that took place at the CIA’s notorious “black sites.”

The two psychologists who helped design and execute the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques” are now at the center of the proceedings in Guantánamo. Last week, Dr. James E. Mitchell testified for four days, and on Monday and Tuesday his testimony continued. His colleague, Dr. Bruce Jessen, is expected to testify later this week. Their appearances constitute one of the most unusual moments in the 18-year history of Guantánamo, because now the men who were at the center of one of the most controversial aspects of U.S. policy are defending their conduct in open court.

The psychologists were called in by attorneys representing defendant Ammar al Baluchi, nephew of co-defendant and alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. On Monday and Tuesday, the defense team for Mohammed, who was waterboarded 183 times by Mitchell and Jessen, questioned Mitchell. Last week, it was attorney James Connell III, representing Baluchi, who spent three days questioning Mitchell. The psychologist started his first day of testimony defiant, then waxed emotional, choking up at one point when asked about why he took the job. “I felt my moral obligation to protect American lives outweighed the temporary discomfort of terrorists who voluntarily took up arms against us,” Mitchell said, holding back tears. “I’d get up today and do it again.”

The courtroom in Guantánamo is a place where your ears are ordinarily filled with details of interrogation sessions in secret locations: descriptions of belly slaps, facial grasps, stress positions, slams against a wall, and “applications” of waterboarding (simulated drowning). Some detainees at Guantánamo have been held for 18 years without charges against them, and others have been charged with crimes of terrorism. Forty men remain in custody of the 780 held here since January 2002, when the first prisoners of the 9/11 era were brought to this island to be kept in American custody without being in America proper.

Guantánamo is more than a courtroom and a prison, of course. It is also a town with galleys staffed by Filipino and Jamaican workers, first-run movies, a school and hair salon, and neighborhoods with single family homes, along with the barracks, trailers, and tents for soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, Coast Guard members, and civilian workers. And it is a tropical island with beaches, lizards, and iguana crossing signs. Food choices include McDonald’s and Subway. The local pub is called O’Kelly’s.

With only a handful of dining choices, it’s no surprise that legal teams, witnesses, and visiting journalists turn up at the same place. Journalists who are covering the hearings kept bumping into the star witness at various locations last week. Walking past a table of reporters in the galley (Navy lingo for a chow hall), Mitchell mistook me for tireless New York Times reporter Carol Rosenberg, who has covered Guantánamo far longer than anyone else. I was greeted courteously by the chief prosecutor, Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, at the pizza joint next to the bowling alley; we used to hear from Martins somewhat regularly, until he stopped giving briefings to reporters in the media office.

Last week marked the 40th pretrial hearings in the death penalty case against the five alleged perpetrators of the 9/11 attack: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al Shibh, Ammar al Baluchi, and Mustafa al Hawsawi. These were the five defendants who were escorted into the courtroom by the gloved guards. Mitchell, the psychologist, sat across the room from them, in the witness box.

The large courtroom is crowded: five defense teams with several lawyers, paralegals, and interpreters on the left, and about a dozen prison escorts wearing camouflage uniforms. Most of the female defense attorneys and staff wear head coverings out of respect for their clients on the days when they are present; the male attorneys all wear the normal lawyer suits and ties. The military lawyers and staff are in uniform.

The large contingent of prosecution attorneys and staff are on the right, led by Martins, always crisply uniformed, with a chest full of medals and badges. His pedigree is unassailable: Martins has degrees from West Point, Oxford, and Harvard Law School. Air Force military judge Col. W. Shane Cohen, sitting on the bench, is the third judge to preside in this case; he was appointed last June.

The jury box is empty for now. These hearings on pretrial motions have been going on since 2012. When the trial begins, now set by Cohen for January 11, 2021, the panel will be made up of military officers flown in for the proceedings.

At the rear of the court, behind a glass wall, is a gallery with four rows of seats for media, nongovernmental observers, and their military escorts. There is also a section reserved for the families of the victims of the attacks. Ten family members attended daily last week, and a curtain was drawn between them and the other observers.

The gallery sees the live scene, but hears the proceedings on a 40-second delay, with the exchanges switching to white noise if classified issues are mentioned. It’s a confusing spectacle: Gestures seen on the monitors in the gallery, and the words that go with them, lag behind what’s happening in front of your eyes. When the judge calls for a break, we’re told by our escorts to rise, even though the monitors above our heads show the judge still seated.

It is a strict atmosphere. Observers are monitored by cameras mounted on the walls and military minders in the gallery. No electronic devices are permitted. Reporters scribble furiously in their notepads as a sketch artist wields her pastels (her sketches must be approved and stamped by an information security officer before she can take them out of the courtroom, and they can’t be altered afterwards).

Last week, Connell, the defense lawyer, pursued questions taken from Mitchell’s 2016 book “Enhanced Interrogation,” and other books by former CIA employees which had undergone prepublication review by the agency. But in a strange twist, a new classification guidance redacts categories of information in those books. This means that although the books contain information that is available to anyone with a library card or enough money to buy a copy, the defense lawyers try not to mention the forbidden categories.

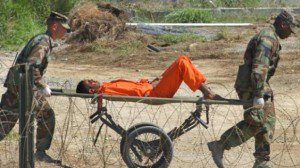

Detainees in orange jumpsuits sit in a holding area at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. CIA’s savagery, kidnapping and torture.

Photograph: U.S. Navy/Getty Images

The countries where the accused and others were held at black sites are cloaked by the classification guidance as Location 2, Location 3, Location 4, and so on. They are identified in the Senate’s 2014 torture report by colors, for instance, COBALT, GREEN, and BLUE. News stories and books about the CIA torture program place those three black sites in Afghanistan, Thailand, and Poland (there were at least five others in various countries).

The black site that held some of these prisoners in Guantánamo in 2003-2004 was only a rumor until the Senate’s report, but now can be named in court. Mitchell was a debriefer at that site for several months, making a distinction from the locations where, in his words, “enhanced interrogation techniques” were “applied.” Mitchell and Jessen’s multiple roles as interrogator, debriefer, and psychologist, and their status as contractors in the black sites, are questioned by the defense as potential conflicts.

Euphemism is a foundation of the torture structure. Even Mitchell railed against some of the words used by the government to describe the program he was pursuing: “You want to watch the use of euphemism for what you’re doing. Don’t be fooled by ‘enhanced interrogation,’ you are doing coercive physical techniques,” he said last week. So there is a euphemism for the euphemism, which in plain English is torture.

Euphemism is a foundation of the torture structure.

As the testimony continues, euphemisms abound. There are code words for locations as well as code numbers and pseudonyms for names. An overlay of psychological terminology tries to give method and reason to examples of physical abuse. These phrases are used: “intelligence requirements,” “abusive drift,” “countermeasures to resistance,” “Pavlovian response,” “learned helplessness,” “negative reinforcement,” “conditioning strategy,” a chart of “moral disengagement.” Torturers used a technique known as “walling,” in which a detainee is thrown against a wall that is described as “safe” because it is made of plywood and constructed to have “bounce.” When walling was used, a beach towel was protectively wrapped around the prisoner’s neck and later became a “Pavlovian” tool that the detainee could be shown to remind him of the suffering he’d endured. This is how torturers speak, cloaking their actions in anodyne language.

During the hearings, CIA cables were either flashed on the overhead monitor if they had been declassified, or remained hidden from our view if they were still secret, recounting the number of slaps, the hours and days of sleep deprivation, the stopwatch counts of waterboard drownings, the rounds of “walling.” The effect is deadening to the observer; it seems part of a bureaucracy of nightmares.

Just yards away from the witnesses, the accused are listening to an Arabic translation of the proceedings. What are they thinking? A lawyer for Hawsawi, Walter Ruiz, said that when he asked his client for a reaction to Mitchell as a witness, Hawsawi said: “Arrogant.”

On Friday, Hawsawi had to leave the courtroom to receive a dose of Tramadol for the pain he has suffered since his detention at a black site in Afghanistan (known as COBALT in the Senate report, or Location 2 in the courtroom’s lingo). Other defense lawyers had no comment from their clients, but said that seeing the interrogator was difficult for them, even more than a decade after their torture.

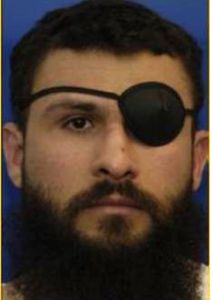

Palestinian Prisoner Abu Zubaydah claims that “a collar was used to slam him against a concrete wall.”

Photo: Department of Defense/MCT via Getty Images

Mitchell’s testimony last week focused on the treatment of Ammar al Baluchi at a CIA black site in Afghanistan. Mitchell did not participate in that interrogation and was willing to discuss the “abusive drift” of another CIA interrogator. This man, who died soon after his retirement in 2003, was identified by the Washington Post more than five years ago as Charlie Wise, but was not named in court during multiple questions and answers about his actions. In court he was referred to only as “NX2,” and Mitchell called him the “new sheriff.” Wise conducted this session of “walling” along with four of his trainees.

“It looked like they used your client as a training prop,” Mitchell told Baluchi’s lawyer. Mitchell sought to put distance between his team and Wise, saying: “We didn’t have them practice on detainees.”

A declassified CIA report, shown to the witness and on monitors in the courtroom and gallery, described what happened that day: “After the session Ammar was returned to his cell naked and placed in the standing sleep deprivation position, hands at eye level, where he will remain until the next interrogation session the following day.” Baluchi apparently stood in that position for 44 hours.

On Friday, after many allusions to an October 2001 statement by an anonymous George W. Bush administration official that “the gloves are off,” the word “torture” was finally spoken by Ruiz, learned counsel for Hawsawi, over objections by the prosecution.

“I know torture’s a dirty word,” Ruiz said. “I’ll tell you what, judge, I’m not going to sanitize this for their concerns.”

Ruiz described what was done to Hawsawi during his interrogations (not by Mitchell, but allegedly by another CIA interrogator). Hawsawi underwent a “bath” where his “ass” and “balls” (the words used by Ruiz in court) and then face were scrubbed with a stiff brush; he was hung naked from the ceiling; his face was slapped; he was placed in stress positions; and he was doused with cold water. Mitchell subsequently participated in a psychological assessment of Hawsawi, which was displayed in the courtroom. Hawsawi was the only defendant in the courtroom watching at the time.

“Did it matter in your assessment that Mr. Al Hawsawi had been tortured in this many ways?” Ruiz asked. “Did it matter to you?”

Mitchell objected to the characterization of Hawsawi’s treatment as “torture.”

Cohen, the judge, responded, “Of course he says no because he doesn’t think it is torture.”

Ruiz then showed a video clip of a 2018 podcast in which Mitchell said: “We never used the word torture. Because torture’s a crime.”

Guantánamo is on a tropical island that tends to be balmy, but extreme weather is not unknown. On Wednesday and Thursday last week, the canvas tents housing nongovernmental observers and journalists were whipped by apocalyptic winds, and on Tuesday at 2:10 pm, tremors from an earthquake in the Caribbean sea rocked the courtroom. After a brief pause, the hearing continued.

_____________________________________________

Related:

- In Guantánamo Case, U.S. Government Says It Can Indefinitely Detain Anyone — Even U.S. Citizens

- We Tortured Some Folks: The Report’s Daniel Jones on the Ongoing Fight to Hold the CIA Accountable

- It’s Still Open: Will the Guantánamo Bay Prison Become a 2020 Issue?

Margot Williams – margot.williams@theintercept.com

Go to Original – theintercept.com

Tags: Abu Ghraib, Bruce Jessen, CIA, Enhanced Interrogation, Guantanamo, History, Human Rights, Invasion, Iraq, James Mitchell, NATO, Occupation, Pentagon, Rendition, State Terrorism, Torture, US Military, USA, Violence, War, Whistleblowing

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.