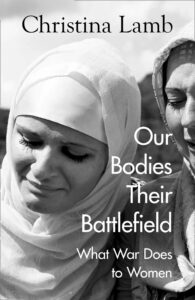

‘The Most Powerful and Disturbing Book That I Have Ever Read’

REVIEWS, 9 Mar 2020

Antony Beevor | The Spectator - TRANSCEND Media Service

A Devastating Exposé of the Systematic Use of Rape in War and Ethnic Cleansing

29 Feb 2020 – I had assumed, after 40 years of researching and writing about war in the 20th century, that I was prepared for just about any horror. But Christina Lamb’s research, into the mass rape of women and young girls in more recent wars and ethnic cleansing shook me to the core. This is the most powerful and disturbing book that I have ever read, and it raises important questions.

Lamb takes us from one zone of racial and religious aggression to another. The attackers have different motives and each persecuted minority is culturally unique, yet the pain and suffering of their victims are terrifyingly similar. She meets the Yazidi women, seized by Isis warriors from their ancient homeland between Syria and Iraq, chosen by lot as sex slaves, then sold on like second-hand cars from one rapist to another. The Muslim Rohingya women in northern Myanmar are violated with conspicuous cruelty by the Buddhist army in order to stampede an entire people over the frontier to Bangladesh.

In Nigeria, Boko Haram kidnaps girls en masse to turn them into ‘bush wives’ to produce another generation of fighters and slaves. ‘I abducted your girls … I will sell them in the market, by Allah,’ declared their leader Abubakar Shekau, after seizing hundreds of schoolgirls. ‘I will marry off a woman at the age of 12. I will marry off a girl at the age of nine.’ Militia groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo sometimes even rape babies and infants because they are led to believe that this will give them special powers, or cure them of HIV.

There have been so many more examples of mass rape in different countries. Bangladeshi women were abused terribly in 1971 by their fellow Muslims from the Pakistan Army in its attempt to crush the independence movement. The Rwandan genocide against the Tutsis was known for its massacres, yet the mass rapes which accompanied them were overlooked at the time. The 2018 report of the UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict named a minimum of 19 states in which women had been raped during recent conflicts. It also listed ‘12 national military and police forces and 39 non-state actors’ as guilty of mass rape.

Rather like the killing of prisoners in wartime, rape has seldom been mentioned in the past, partly because it might have been embarrassing to think that one’s own side might also be guilty, but also because of an assumption that it had always been a natural part of war. ‘For decades there was little discussion,’ Lamb writes. ‘It took rape camps being set up again in the heart of Europe for the issue to get international attention. Like many people, the first time I heard of sexual violence in conflict was in the 1990s during the war in Bosnia.’ And yet rape had certainly not been absent from the ideological conflicts of the first half of the century.

In the Spanish Civil War, officers in Franco’s Army of Africa, during their advance on Madrid in the late summer and early autumn of 1936, urged their Moroccan troops to rape, and in many cases disembowel, the wives and daughters of peasants and workers as a deliberate act of terror to panic the Republican militias. The greatest example of all took place in 1945, as soldiers in the Red Army raped an estimated two million German women, tens of thousands of Hungarians, and even those women of supposedly Allied nations, such as Poles and Serbs. The Imperial Japanese Army did not restrict itself to the perpetual rape of ‘comfort women’ imprisoned in military brothels. They also believed in the gang rape of enemy civilians as a form of comradeship bonding.

Lamb’s book should certainly provoke much debate and I hope it will also clarify some thinking. Perhaps the phrase ‘rape as a weapon of war’ has become too much of a standard term. In many cases it is correct, although a more accurate version would be ‘a weapon of terror in conflict and ethnic cleansing’. Yet much depends on whether the ‘weapon’ is a deliberate military policy. It certainly was with the Pakistani Army in Bangladesh, Franco’s Army of Africa, the Japanese Army and the Myanmar Army, along with all the other acts of ethnic cleansing.

But there are also examples of where an army has slipped its leash, and soldiers simply exploit the opportunity. In the case of the Red Army, the position was complex. Soviet propaganda had dehumanised the ‘Fascist beast’, and even the ‘blonde witch’, with calls for vengeance, yet many officers and soldiers were horrified by what their comrades did and took no part in it. A number even saved German women. So, we do need to be careful about generalisations.

The feminist definition of rape is that it is an act of violence driven by a compulsion to exert power, and has nothing to do with sex. But that is naturally the victim’s point of view and does little to explain the motivation of the perpetrator. All the sadistic acts, which Lamb quite rightly does not spare us, clearly support that perspective. The dehumanisation of the enemy, which needs to be heightened by a strong dose of fear along with the hatred, is also another part of the weapon of terror. But men’s motives to rape in war obviously vary, from sheer sexual opportunism to the fanatical compulsion to hurt, humiliate, pollute, disfigure and even kill their female victims. And as the Red Army example showed, not all men become rapists, even when they face no retribution. Also, to refute the black and white approach, Susan Brownmiller acknowledged in her seminal work on the subject, Against Our Will, there is even the ‘grey area of wartime prostitution’, where men with food, as well as guns, can exploit another form of power.

The very phrase ‘weapon of war’ also unintentionally reinforces that old mistake of including rape as a natural part of the landscape of armed conflict. Unfortunately, as Lamb emphasises, in the few recent cases where perpetrators have been brought to trial, prosecutors tend to drop the rape charges when they find it easier to convict on the more general charge of terrorism. That is no comfort whatsoever to the women who have had to summon up great courage to appear as witnesses.

The vast majority of victims suffer twice. Those who survive their ordeals then have to face ostracism from their own families and communities. They are seen as polluted. Many commit suicide, unable to cope with the contempt and shame heaped upon them. Most of the rest, whatever culture they come from, describe feeling ‘dead inside’. It is very hard to enjoy normal human relations after an assault intended to dehumanise one. And how can one trust anyone again when, in the case of ethnic cleansing, former friendly neighbours become savage aggressors? As Lamb argues, the survivors are heroic. Mercifully for the male reader, there are some heroes too on their side of the fence, principally rescuers and doctors.

It must also have taken courage to research and write this book. When you tackle such horrors, they have a way of coming back to haunt you in the dark watches of the night. In 1944, a traumatised Vasily Grossman wrote, after producing the very first report on the atrocities of the Treblinka extermination camp: ‘It is the writer’s duty to tell this terrible truth, and it is the civilian duty of the reader to learn it.’

Christina Lamb has more than accomplished her duty. It is now our duty to face this other ‘terrible truth’ — that of man’s inhumanity to woman.

Tags: Reviews, War, Women Rights

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.