One of those documents, the first to be made public in June 2013, revealed that the NSA was tracking billions of telephone calls made by Americans inside the US. The program became notorious, but its full story has not been told.

The first accounts revealed only bare bones. If you placed a call, whether local or international, the NSA stored the number you dialed, as well as the date, time and duration of the call. It was domestic surveillance, plain and simple. When the story broke, the NSA discounted the intrusion on privacy. The agency collected “only metadata,” it said, not the content of telephone calls. Only on rare occasions, it said, did it search the records for links among terrorists.

I decided to delve more deeply. The public debate was missing important information. It occurred to me that I did not even know what the records looked like. At first I imagined them in the form of a simple, if gargantuan, list. I assumed that the NSA cleaned up the list—date goes here, call duration there—and converted it to the agency’s preferred “atomic sigint data format.” Otherwise I thought of the records as inert. During a conversation at the Aspen Security Forum that July, six weeks after Snowden’s first disclosure and three months after the Boston Marathon bombing, Admiral Dennis Blair, the former director of national intelligence, assured me that the records were “stored,” untouched, until the next Boston bomber came along.

Even by that account, the scale of collection brought to mind an evocative phrase from legal scholar Paul Ohm. Any information in sufficient volume, he wrote, amounted to a “database of ruin.” It held personal secrets that “if revealed, would cause more than embarrassment or shame; it would lead to serious, concrete, devastating harm.” Nearly anyone in the developed world, he wrote, “can be linked to at least one fact in a computer database that an adversary could use for blackmail, discrimination, harassment, or financial or identity theft.” Revelations of “past conduct, health, or family shame,” for example, could cost a person their marriage, career, legal residence, or physical safety.

Mere creation of such a database, especially in secret, profoundly changed the balance of power between government and governed. This was the Dark Mirror embodied, one side of the glass transparent and the other blacked out. If the power implications do not seem convincing, try inverting the relationship in your mind: What if a small group of citizens had secret access to the telephone logs and social networks of government officials? How might that privileged knowledge affect their power to shape events? How might their interactions change if they possessed the means to humiliate and destroy the careers of the persons in power? Capability matters, always, regardless of whether it is used. An unfired gun is no less lethal before it is drawn. And in fact, in history, capabilities do not go unused in the long term. Chekhov’s famous admonition to playwrights is apt not only in drama, but in the lived experience of humankind. The gun on display in the first act—nuclear warheads, weaponized disease, Orwellian cameras tracking faces on every street—must be fired in the last. The latent power of new inventions, no matter how repellent at first, does not lie forever dormant in government armories.

These could be cast as abstract concerns, but I thought them quite real. By September of that year, it dawned on me that there were also concrete questions that I had not sufficiently explored. Where in the innards of the NSA did the phone records live? What happened to them there? The Snowden archive did not answer those questions directly, but there were clues.

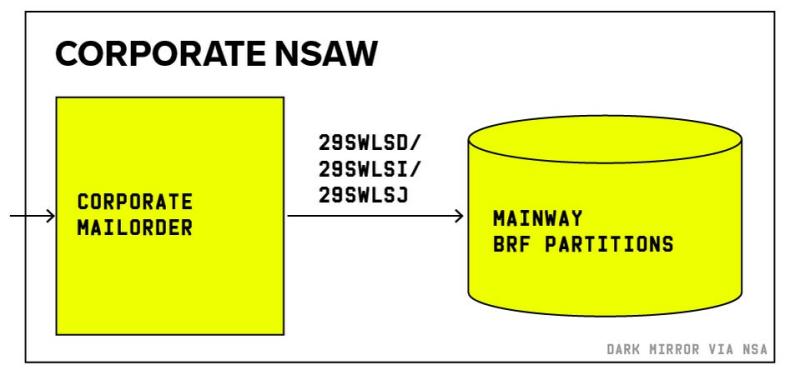

The diagram as a whole, too large to display in full, traced a “metadata flow sourced from billing records” at AT&T as they wended through a maze of intermediate stops along the way to Fort Meade. Mailorder, the next to last stop, was an electronic traffic cop, a file sorting and forwarding system. The ultimate destination was Mainway. The “BRF Partitions” in the network diagram were named for Business Records FISA orders, among them a dozen signed in 2009 that poured the logs of hundreds of billions of phone calls into Mainway.

The diagram as a whole, too large to display in full, traced a “metadata flow sourced from billing records” at AT&T as they wended through a maze of intermediate stops along the way to Fort Meade. Mailorder, the next to last stop, was an electronic traffic cop, a file sorting and forwarding system. The ultimate destination was Mainway. The “BRF Partitions” in the network diagram were named for Business Records FISA orders, among them a dozen signed in 2009 that poured the logs of hundreds of billions of phone calls into Mainway.