“The Atlas of Surveillance database, containing several thousand data points on over 3,000 city and local police departments and sheriffs’ offices nationwide, allows citizens, journalists, and academics to review details about the technologies police are deploying, and provides a resource to check what devices and systems have been purchased locally,” EFF announced on July 13.

Users can click on the map to see what surveillance technologies are used in specified localities. If you want to see what’s going on in your area, the map is searchable by the name of a city, county, or state. The map can also be filtered according to technologies such as body-worn cameras, drones, and automated license plate readers.

The nearest entry to me is in Prescott Valley, Arizona, where the police department is among the hundreds that have partnered with Ring, the Amazon-owned doorbell-camera company.

The Ring partnerships don’t give police live feeds, but they can request video recordings regarding a specific time and area. While participation by Ring customers is voluntary, the partnerships are “a clever workaround for the development of a wholly new surveillance network, without the kind of scrutiny that would happen if it was coming from the police or government,” warns Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, a professor at the University of the District of Columbia’s David A. Clarke School of Law and author of The Rise of Big Data Policing.

Researchers find few crimes solved by the voluntary surveillance partnerships, but the home-security marketing of the Ring arrangement nudges the culture toward an easier acceptance of a panopticon that operates outside of the full range of civil liberties protections.

Also easing America’s slide toward a full surveillance state is fear of the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health officials who, just months ago, fretted about overcoming privacy concerns with regard to contact-tracing schemes have turned to governments’ usual solution: threatening harsh penalties for noncompliance.

“Travelers from certain states landing at New York airports starting Tuesday could face a $2,000 fine for failing to fill out a form that state officials will use to track travelers and ensure they’re following quarantine restrictions,” AP reported this week.

Mandatory tracking forms for travelers to New York follow on Rockland County’s earlier efforts to compel cooperation with contact tracers.

“Commissioner of Health Dr. Patricia Schnabel Ruppert urged residents to comply with the Department of Health’s contact tracing efforts and threatened those who do not comply with subpoenas and $2,000 per day fines,” the county announced on July 1.

We can hope that health-related snooping into people’s movements and activities will come to an end when the pandemic passes, but these things have a way of getting embedded in the culture as people become accustomed to them. In the name of controlling infection, many private companies are now closely monitoring employees, including their proximity to one another in the workplace.

“Privacy advocates warn the tracing apps are a slippery slope toward ‘normalizing’ an unprecedented new level of employer surveillance,” notes Politico.

“Aggressive expansion of surveillance programs without adequate checks could normalize privacy intrusions and create systems that may later be used for various forms of political and social repression,” frets Freedom House.

That novel invasions of privacy which might once have set off alarms can become the new normal is clear from public-private surveillance partnerships of the sort that Ring developed with police departments. After the Supreme Court ruled that police need a warrant to access cellphone location data in Carpenter v. United States (2018), law enforcement quickly started purchasing data from private marketing firms.

“The Trump administration has bought access to a commercial database that maps the movements of millions of cellphones in America and is using it for immigration and border enforcement,” the Wall Street Journal reported earlier this year. “Experts say the information amounts to one of the largest known troves of bulk data being deployed by law enforcement in the U.S.—and that the use appears to be on firm legal footing because the government buys access to it from a commercial vendor.”

In a growing trend, other agencies, including the FBI and the IRS, have also turned to private sources to monitor social media posts and track cellphone movements. The new surveillance technique is quickly becoming widely established.

Likewise, even after COVID-19 fades to an unpleasant memory, we may find that it has left a legacy of intrusive monitoring of our whereabouts and social connections—all for our own good, we’ll be told.

For now, the growing incidence of public health surveillance is too new and low-tech to be included in the Atlas of Surveillance, which is plenty full as it is.

Selecting “automated license plate readers” reveals dense clusters in California, and in urban areas and along major highways elsewhere.

Clicking on “drones” reveals that they monitor much of the country—especially east of the Mississippi River and along the West Coast—from the sky.

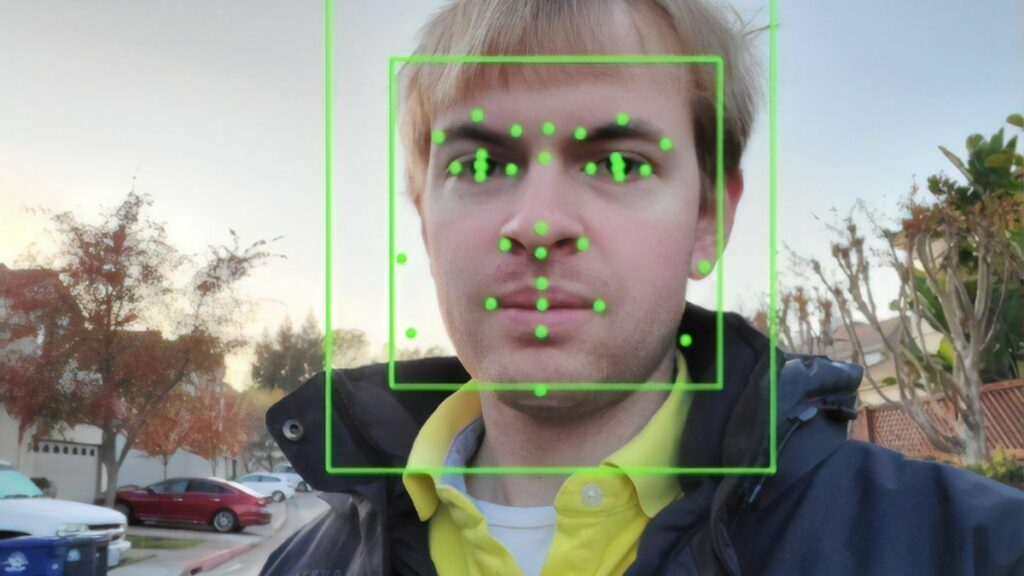

A look at “face recognition technology” shows that it is especially popular in Florida and around Washington, D.C.

As thoroughly monitored as the atlas reveals the country to be, it’s far from complete and EFF invites volunteers to assist in collecting data. As new information trickles in, that map will undoubtedly fill in with new jurisdictions and surveillance efforts as time goes on.

The Atlas of Surveillance will probably fill in with new monitoring technologies, too, including some driven by public health concerns. For officials looking for reasons to poke their noses into other people’s business, the pandemic is as good an excuse as any.