“I think people often confuse what wealthy people are doing on their own dime and what [they’re] doing on our dime, and that’s one of the big problems about this debate,” Madoff notes. “People say, ‘It’s the rich person’s money [to spend as they wish].’ But when they get significant tax benefits, it’s also our money. And so that’s why we need to have rules about how they spend our money.”

Naturally, Big Philanthropy has special interest groups pushing back on the creation of such rules. The Philanthropy Roundtable defends the wealthiest Americans’ “freedom to give,” describing itself as fighting the “increasing pressures from some public officials and advocacy groups to subject private philanthropies to more uniform standards and stricter government regulation.”

The nonprofit group receives funding from influential right-wing billionaires, including hundreds of thousands of dollars from the private foundation of Charles Koch. And it gets substantial funding from the Gates Foundation: nine grants from 2005 to 2017, worth $2.5 million, mostly for general operating expenses. A spokesperson for the foundation says these donations are aimed at “mobilizing voices to advocate for public policies that further enable charitable giving.”

At a certain point, however, the Philanthropy Roundtable seems primarily to serve the private interests of billionaires like the Gateses and Koch who use charity to influence public policy, with limited oversight and substantial public subsidies. It’s unclear how the Philanthropy Roundtable’s work contributes to the Gates Foundation’s charitable missions “to help all people live healthy, productive lives” and “to empower the poorest in society so they can transform their lives.”

While there is no credible argument that Bill and Melinda Gates use charity primarily as a vehicle to enrich themselves or their foundation, it is difficult to ignore the occasions where their charitable activities seem to serve mainly private interests, including theirs—supporting the schools their children attend, the companies their foundation partly owns, and the special interest groups that defend wealthy Americans—while generating billions of dollars in tax savings.

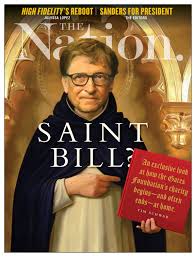

Philanthropy has also delivered a public relations coup for Bill Gates, dramatically transforming his reputation as one of the most cutthroat CEOs to one of the most admired people on earth. And his model of charity, influence, and absolution is inspiring a new era of controversial tech billionaires like Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos, who have begun giving away their billions, sometimes working directly with Gates.

Gates was already one of the richest humans on earth in 2008, but he was also an embattled billionaire, still licking his wounds from a series of legal battles around the monopolistic business practices that made him so extravagantly wealthy—and that compelled Microsoft to pay billions of dollars in fines and settlements.

Gates did not respond to multiple requests for interviews, but in a recent Q&A with The Wall Street Journal, he revisited his legal face-off with antitrust regulators, saying, “I can still explain to you why the government was completely wrong, but that’s really old news at this point. For me personally, it did accelerate my move into that next phase, two to five years sooner, of shifting my focus over to the foundation.”

Gates’s view of Microsoft as the victim of overzealous antitrust regulations may help explain the laissez-faire ethos driving his charitable giving. His foundation has given money to groups that push for industry-friendly government policies and regulation, including the Drug Information Association (directed by Big Pharma) and the International Life Sciences Institute (funded by Big Ag). He has also funded nonprofit think tanks and advocacy groups that want to limit the role of government or direct its resources toward helping business interests, like the American Enterprise Institute ($6.8 million), the American Farm Bureau Foundation ($300,000), the American Legislative Exchange Council ($220,000), and organizations associated with the US Chamber of Commerce ($15.5 million).

Between 2011 and 2014 the Gates Foundation gave roughly $100 million to InBloom, an educational technology initiative that dissolved in controversy around privacy issues and its collection of personal data and information about students. To Diane Ravitch, a professor of education at New York University, InBloom illustrates the way Gates is “working to push technology in classrooms, to replace teachers with computers.”

“That affects Microsoft’s bottom line,” Ravitch observes. “However, I’ve never made that argument…. [The foundation] is not looking to make money from this business. They have an ideological interest in free markets.”

Education isn’t the only area where Gates’s ideological interests overlap with his financial interests. Microsoft’s bottom line is heavily dependent on patent protections for its software, and the Gates Foundation has been a strong and consistent supporter of intellectual property rights, including for the pharmaceutical companies with which it works closely. These patent protections are widely criticized for making lifesaving drugs prohibitively expensive, particularly in the developing world.

“He uses his philanthropy to advance a pro-patent agenda on pharmaceutical drugs, even in countries that are really poor,” says longtime Gates critic James Love, the director of the nonprofit Knowledge Ecology International. “Gates is sort of the right wing of the public-health movement. He’s always trying to push things in a pro-corporate direction. He’s a big defender of the big drug companies. He’s undermining a lot of things that are really necessary to make drugs affordable to people that are really poor. It’s weird because he gives so much money to [fight] poverty, and yet he’s the biggest obstacle on a lot of reforms.”

The Gates Foundation’s sprawling work with for-profit companies has created a welter of conflicts of interest, in which the foundation, its three trustees (Bill and Melinda Gates and Buffett), or their companies could be seen as financially benefiting from the group’s charitable activities.

Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has billions of dollars in investments in companies that the foundation has helped over the years, including Mastercard and Coca-Cola. Bill Gates long sat on the board of directors at Berkshire, announcing his departure just last week, and he and his foundation together hold billions of dollars of equity stake in the investment firm.

The foundation’s work also appears to overlap with Microsoft’s, to which Gates, in recent years, has devoted one-third of his workweek. (Gates announced last week he would be stepping down from the company’s board, but remain involved with the company as a technology advisor). The Gates Foundation’s $200 million program to improve public libraries partnered with Microsoft to donate the company’s software, prompting criticism that the donations were aimed at “seeding the market” for Microsoft products and “lubricating future sales.” Elsewhere, Microsoft is investing money studying mosquitoes to help predict disease outbreaks, working with the same researchers as the foundation. Both projects involve creating sophisticated robots and traps to collect and analyze mosquitoes.

“The foundation and Microsoft are separate entities, and our work is wholly unrelated to Microsoft,” a Gates Foundation spokesperson says.

In 2002, The Wall Street Journal reported that Gates and the Gates Foundation’s endowment made new investments in Cox Communications at the same time that Microsoft was in discussion with Cox about a variety of business deals. Tax experts raised questions about self-dealing, noting that foundations can lose their tax-exempt status if they are found to be using charity for personal gain. The IRS would not comment on whether it investigated, saying, “Federal law prohibits us from discussing specific taxpayers or organizations.”

Gates is notoriously secretive about his personal investments, however, making it difficult to understand if he stands to gain financially from his foundation’s activities or the extent to which he does if this happens.

“It’s hard to draw the line between a) Microsoft; b) his own personal wealth and investment; and c) the foundation,” says consumer advocate Ralph Nader, one of Microsoft’s fiercest critics in the 1990s. “There’s been very inadequate media scrutiny of all that.”

The foundation’s clearest conflicts of interest may be the grants it gives to for-profit companies in which it holds investments—large corporations like Merck and Unilever. A foundation spokesperson said it tries to avoid this kind of financial conflict but that doing so is difficult because its investment and charitable arms are firewalled from one another to keep their activities strictly separate. Bill and Melinda Gates are trustees of both entities, however, making it difficult to draw a sharp line between the two.

And in some places, the Gates Foundation explicitly marries its investing and charitable activities. Gates’s “strategic investment fund,” which the foundation says is designed to advance its philanthropic goals, not to generate investment income, includes a $7 million equity stake in the start-up company AgBiome, whose other investors include the agrochemical companies Monsanto and Syngenta. The foundation also gave the company $20 million in charitable grants to develop pesticides for African farmers. Similarly, the foundation has a $50 million stake in Intarcia and an $8 million investment in Just Biotherapeutics, to which it gave $25 million and $32 million in charitable grants, respectively, for work related to HIV and malaria. At one point, the foundation held a 48 percent stake in an HIV diagnostic company called Zyomyx, to which it previously awarded millions of dollars in charitable grants.

Asked about these apparent conflicts of interest, the foundation says that grants and investments “are simply two tools the foundation uses as appropriate to further its charitable objectives.”

When Gates began his foundation in 1994, he put his father, Bill Gates Sr., in charge. A prominent lawyer in Seattle, Gates Sr. was also a civic leader and, later, a public advocate on issues related to income inequality.

Working with Chuck Collins, an heir to the Oscar Mayer fortune who gave away much of his inheritance during his 20s, Gates Sr. helped organize a successful national campaign in the late 1990s and early 2000s to build political power around preserving the estate tax, the taxes levied against the assets of the wealthy after they die.

In interviews Gates Sr. gave at the time (he has Alzheimer’s disease now and was not contacted for an interview), his advocacy work seemed designed not to generate tax revenues but to inspire philanthropy.

“A wealthy person has an absolute choice as to whether they pay the [estate] tax or whether they give their wealth to their university or their church or their foundation,” he told journalist Bill Moyers.

That’s because when the rich give away their wealth, they reduce the assets that the estate tax targets. But such an arrangement, whereby the wealthiest Americans get to decide for themselves whether they want to pay taxes or donate their money to charity—including to groups that influence government policy—sounds like a peak example of tone-deaf privilege. In many respects, that’s how the tax system works for the superrich.

“The richer you are, the more choice you have between those two,” says Collins, who today works on income inequality at the nonprofit Institute for Policy Studies.

For some billionaire philanthropists, it may be less of a choice than an entitlement. Buffett and Gates have recruited hundreds of millionaires and billionaires to sign the Giving Pledge, a promise to donate most of their wealth to charity, which some signatories explicitly cite as an alternative to paying taxes.

According to Collins, Bill Gates Sr. had a nuanced view that included limiting billionaires’ tax benefits.

“He said to me…it’s a problem that his son is going to give—at the time, it was like $80 billion—to the foundation and never have to pay taxes on any of that wealth,” Collins recalls. “His view was that there should be a cap on the lifetime amount of wealth that could be given to charity where you get a deduction.”

Around the time that Collins and Gates Sr. were putting pressure on Congress to make sure the wealthy pay their fair share of taxes, the younger Gates was running a multinational company aggressively looking for tax breaks. According to the assessor’s office for King County, which includes Seattle, Microsoft has filed 402 appeals on its property taxes. Likewise, a 2012 Senate investigation examined Microsoft’s aggressive use of offshore subsidiaries to save the company billions of dollars in taxes. And The Seattle Times reported that Microsoft spent decades creating lucrative, tax-reducing barriers around corporate profits.

Bill Gates, nevertheless, has managed to become a leading—and seemingly progressive—public voice on tax policy. Every year around tax time, he and Buffett make media appearances decrying how little they pay in taxes, calling on Congress to raise taxes on the wealthy. At times, however, they advocate policies that may not actually touch their wealth, such as promoting the estate tax, which they will likely avoid through charitable donations.

Gates, along with a growing chorus of billionaires, has also used his public platform to push back on a proposed wealth tax, supported by both Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. A wealth tax would take a percentage of a billionaire’s assets every year, limiting the accumulation of wealth—and possibly the amount of money spent on philanthropy. Gates counters that charity work reduces income inequality.

“Philanthropy done well not only produces direct benefits for society, it also reduces dynastic wealth,” he wrote on his blog, GatesNotes.

When the Gates foundation has faced criticism in regard to its endowment—including investments in prisons, fast food, the arms industry, pharmaceutical companies, and fossil fuels—conflicting with its charitable mission to improve health and well-being, Gates has pushed back in black-and-white terms, calling divestment a “false solution” that will have “zero” impact.

The Gates Foundation’s investments are not an insignificant part of its charitable efforts. Its $50 billion endowment has generated $28.5 billion in investment income over the last five years. During the same period, the foundation has given away only $23.5 billion in charitable grants.

In 2007, in one of the few investigative journalism series ever published about the foundation, the Los Angeles Times profiled the foundation’s investments in mortgage lenders involved in subprime loans and for-profit hospitals accused of performing unneeded surgeries. The Times also noted the foundation’s investments in chocolate companies that depend on cocoa production using child labor.

The Gates Foundation spokesperson says it “does not comment on specific investment decisions or holdings,” but did note that the “sole purpose” of its endowment is “to provide income to support the Foundation’s mission and to be capable to do so over the long term.”

The Gates Foundation’s endowment currently has an $11.5 billion stake in Berkshire Hathaway, which in turn has $32 million invested in the chocolate company Mondelez, which has been criticized in relation to the use of child labor. The foundation made $32.5 million in charitable donations to the World Cocoa Foundation, an industry group whose members include Mondelez, for a project to improve farmer livelihoods. The project doesn’t appear to address child labor.

The tax reform act of 1969 created special rules to limit the influence that wealthy philanthropists could exercise through private foundations—in theory ensuring they produce public benefits rather than serve private interests.

In practice, these rules give wealthy donors like Bill and Melinda Gates enormous latitude in their philanthropic activities. For example, when it comes to self-dealing, the IRS prohibits only the most egregious conflicts of interest, such as foundations awarding grants to companies controlled by board members. Likewise, IRS rules broadly allow charitable donations to for-profit companies, as long as the foundations keep paperwork showing that the money was used to advance their charitable missions.

But because the Gates Foundation views market-based solutions and private-sector innovation as public goods, the line between charity and business can be indistinguishable. Sociologist Linsey McGoey says, “They’ve defined their charitable mission so broadly and loosely that literally any for-profit company could be said to be meeting the Gates Foundation’s general goal of improving social and global well-being.”

The IRS’s oversight of private foundations is constrained by recent budget cuts and its limited mandate to collect taxes from nonprofits like the Gates Foundation, which are largely free from paying them.

“If you’re the IRS commissioner and you’re given a finite sum to spend on the agency, and your job is to make sure the US Treasury has money in it, you are going to give a token nod to tax-exempt organizations,” says Marc Owens, a former director of the IRS’s tax-exempt division who is now in private practice. “One [IRS] agent looking at restaurants in Washington or New York City is going to generate a lot of money…. One agent looking at private foundations will probably pay their salary, but it’s not going to bring in tax dollars.”

According to IRS statistics, there are around 100,000 private foundations in the United States, housing close to $1 trillion in assets. However, foundations generally pay a tax rate of only 1 or 2 percent, and the IRS reports auditing, at most, 263 foundations in 2018.

State attorneys general can exercise oversight of private foundations, as the New York attorney general’s office did in 2018 when it investigated Donald Trump’s private foundation, which shut down amid allegations that he used it for his personal benefit. The Gates Foundation’s location in Seattle gives the state of Washington purview over its charitable work, but the state attorney general’s office there says it did not have full-time staff dedicated to investigating charitable activities until 2014, a decade after the foundation became the largest philanthropy in the world. The Washington AG’s office would not comment on whether it has ever investigated the Gates Foundation.

Bill Gates’s outsize charitable giving—$36 billion to date—has created a blinding halo effect around his philanthropic work, as many of the institutions best placed to scrutinize his foundation are now funded by Gates, including academic think tanks that churn out uncritical reviews of its charitable efforts and news outlets that praise its giving or pass on investigating its influence.

In the absence of outside scrutiny, this private foundation has had far-reaching effects on public policy, pushing privately run charter schools into states where courts and voters have rejected them, using earmarked funds to direct the World Health Organization to work on the foundation’s global health agenda, and subsidizing Merck’s and Bayer’s entry into developing countries. Gates, who routinely appears on the Forbes list of the world’s most powerful people, has proved that philanthropy can buy political influence.

Gates’s personal wealth is greater today than ever before, around $100 billion, and at only 64 years of age, he may have decades left to donate this money, picking up a Nobel Prize along the way or—who knows?—a presidential nomination. The same could be said of Melinda Gates, who, at 55, recently took a big step into public life with a highly publicized book tour.

But it’s also possible that a day of reckoning is coming for Big Philanthropy, Bill Gates, and the growing number of billionaires following his footsteps into charity.

Economists, politicians, and journalists continue to put a spotlight on billionaires who aren’t paying their fair share of taxes but who shape politics through campaign contributions and lobbying. Charity is seldom regarded as a tax-avoiding tool of influence, but if income inequality continues to gain attention, there is simply no way to avoid asking tough questions of Big Philanthropy. Do billionaire philanthropists have too much power, with too little public accountability or transparency? Should the wealthiest Americans have carte blanche to spend their wealth any way they want?

It may seem like a radical proposition to challenge the ability or desire of multibillionaires to give away their fortunes, but such scrutiny has a historical precedent in mainstream politics. One hundred years ago, when oil baron John D. Rockefeller asked Congress to provide him with a charter to start a private foundation, his ambitions were soundly rejected as an anti-democratic power grab. As Theodore Roosevelt said at the time, “No amount of charities in spending such fortunes can compensate in any way for the misconduct in acquiring them.”

__________________________________________