Conspiracy theories have a long history, but the actual term “conspiracy theory” emerged much more recently. It was only a few decades ago that the term took on the derogatory connotations it has today, where to call someone a conspiracy theorist functions as an insult.

So it may come as no surprise that there is even a conspiracy theory about the origins of the label. This conspiracy theory claims that the CIA invented the term in 1967 to disqualify those who questioned the official version of John F Kennedy’s assassination and doubted that his killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, had acted alone.

There are even two versions of this conspiracy theory. The more extreme version claims that the CIA literally invented the term in the sense that the words “conspiracy” and “theory” had never been used before in combination. A more moderate version acknowledges that the term existed before, but claims that the CIA intentionally created its negative connotations and so turned the label into a tool of political propaganda.

This article is part of a series tied to the Expert guide to conspiracy theories, a series by The Conversation’s The Anthill podcast. Listen here, on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, or search for The Anthill wherever you get your podcasts.

The more moderate version has been particularly popular in recent years for two reasons. First, it is very easy to disprove the more extreme claim that the CIA actually invented the term. As a search on Google Books quickly reveals, the term “conspiracy theory” emerged around 1870 and began to be more frequently used during the 1950s. Even die-hard conspiracy theorists have a hard time trying to ignore this. Second, the more moderate version received a big boost in popularity a few years ago when American political scientist Lance DeHaven-Smith propagated it in a book published by a renowned university press.

Smoking gun

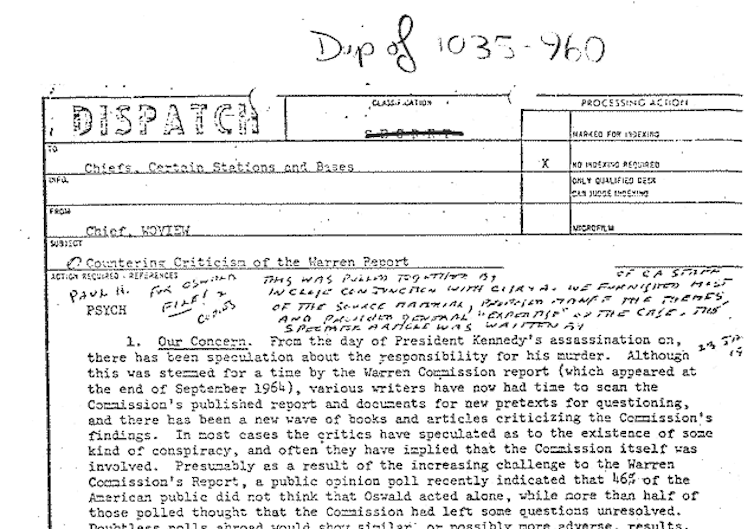

Although they make differing claims about the origin and development of the term, the proponents of both versions invariably point to an official CIA document called Concerning Criticism of the Warren Report as their smoking gun. It was released in 1976 after The New York Times requested it under the Freedom of Information Act.

The document expresses concern about the considerable number of people who doubted the official investigation into Kennedy’s murder, the Warren Commission, which found that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. It also aims to equip CIA contacts with arguments against those who challenge the findings and the official version of the event. For example, it emphasises that nobody in their right mind would have chosen someone as unstable as Oswald as a pawn in a larger plot. And it points out the logical fallacies of these alternative accounts.

One may find the CIA’s attempt to influence public opinion problematic. But there is not a single sentence in the document that indicates the CIA intended to weaponise, let alone introduce the term “conspiracy theory” to disqualify criticism. In fact, “conspiracy theory” in the singular is never used in the document. “Conspiracy theories” in the plural is only used once, matter-of-factly in the third paragraph:

Conspiracy theories have frequently thrown suspicion on our organisation, for example, by falsely alleging that Lee Harvey Oswald worked for us.

The authors of the document deploy the term in a very casual manner and obviously do not feel the need to define it. This indicates that it was not a new term but already widely used at the time to describe alternative accounts. At no time do the authors recommend using the label “conspiracy theory” to stigmatise alternative explanations of Kennedy’s assassination. This suggests that the term had not yet acquired the same level of negativity it possesses today.

Why people believe it

The far more interesting issue, for me, is why this conspiracy theory emerged and why so many people believe in it. No scholar has yet fully charted the course of this particular theory, so it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when it emerged. But it is safe to assume that it was during the 1980s or 1990s based on cursory investigations.

It was only in the 1980s that the term “conspiracy theory” began to really have the negative connotations we associate with it today. So the conspiracy theory about the term’s origins was likely a reaction to this growing negativity.

The reason why so many people believe in the idea that the CIA invented the term “conspiracy theory” relates to the role of the Kennedy assassination in the larger history of the concept and their popularity. It may seem that we are living in an age of conspiracy theory, but such theories were even more popular in the past.

From at least the 17th century to the 1950s, conspiracy theories were a widely accepted way of understanding the world and often the official versions of events. They were articulated by elites and usually targeted external enemies or subversives who were allegedly trying to undermine the state. It was only during the late 1950s and early 1960s that conspiracy theories started to become a stigmatised way of explaining big events.

One side-effect of this move from the mainstream to the margins of society was that conspiracy theories started to primarily target societal and political elites. They are no longer concerned with alleged plots against the state but with those orchestrated by the state.

Another side-effect of this new stigma was that the label conspiracy theory or theorist became a pejorative term. The Kennedy assassination was the first major instance in which conspiracy theorists accused the state of secretly plotting evil and provided alternative accounts that were then labelled conspiracy theories, as in the 1967 CIA document. So it is hardly surprising that conspiracy theorists – who blame events on the intentional actions of evil people – retrospectively see the emergence of the term as a deliberate attempt to uphold the official version of the Kennedy assassination.

_________________________________________

Professor of American Literary and Cultural History, University of Tübingen

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons license.

Go to Original – theconversation.com