Freeing “Hotel Rwanda” Hero Paul Rusesabagina

AFRICA, 19 Oct 2020

Ann Garrison | Black Agenda Report – TRANSCEND Media Service

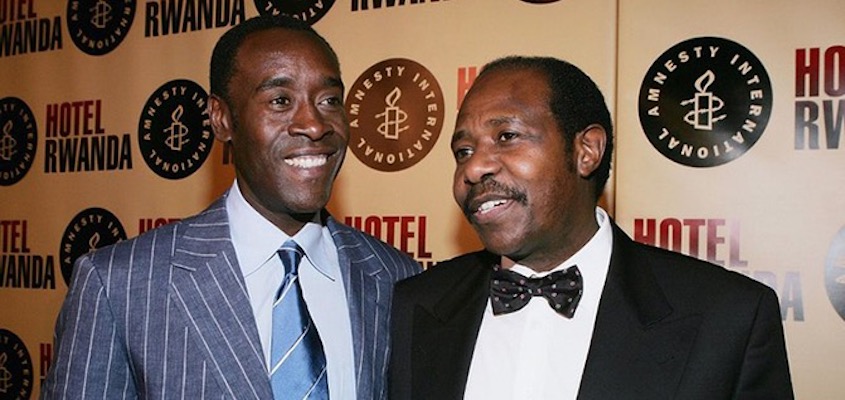

The man portrayed by Don Cheadle in the movie about mass slaughter in Rwanda was kidnapped and jailed by the country’s dictator.

14 Oct 2020 – Paul Rusesabagina, the real life hero whose story is the basis of the movie “Hotel Rwanda,” was kidnapped in Dubai and illegally rendered to Rwanda to stand trial on terrorism charges at the end of August. I spoke to Dan Kovalik, University of Pittsburgh Law School Professor, about possibilities for setting him free. Kovalik is an expert in labor and international human rights law and the author of No More War: How the West Violates International Law by Using ‘Humanitarian’ Intervention to Advance Economic and Strategic Interests .

****************

Ann Garrison: Dan Kovalik, what have you been able to determine about Paul Rusesabagina’s legal situation?

Dan Kovalik: Well, it’s pretty clear that he was kidnapped while he was visiting in Dubai, and then illegally rendered to Rwanda to be tried on what clearly are trumped up charges that he allegedly was supporting some armed militia accused of attacking civilians, which just seems outlandish.

AG: Outlandish indeed. It’s hard to think of a gentler person than Paul Rusesabagina, or to think of one who would be more opposed to any sort of attack on civilians.

DK: I believe he was living in Texas.

AG: San Antonio.

DK: And he had been there because he feared that he would be arrested if he were in Rwanda because he questions the official narrative of the 1994 genocide, and that in itself is illegal in Rwanda. You can’t question the legally codified narrative, but that’s a travesty in any country that claims to guarantee freedom of expression.

AG: As Rwanda does.

DK: Rwanda was no doubt determined to go after him because he has to be the most prominent Rwandan challenging the official narrative of the genocide.

AG: Which is the foundational justification of Kagame’s brutal totalitarian rule and occupation of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“He questions the official narrative of the 1994 genocide, and that in itself is illegal in Rwanda.”

DK: Exact. But even if there were bonafide charges against him in Rwanda, you can’t just go around kidnapping people. That is unquestionably illegal under international law. If they had charges against him, they should have gone into court and tried to have him legally extradited either from the United States or from Dubai. And that would have required them to show some cause to those countries, for arresting him.. So there has to be some sort of concerted effort to get him out of Rwanda.

“You can’t just go around kidnapping people.”

AG: Where is the codification that makes this illegal under international law?

DK: Well, this would violate a number of UN conventions. The one that first comes to mind is the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights , which lays out very specific due process requirements that countries have to follow in an extradition case. That’s a binding covenant, and the US is even signatory to it. As you know, the US rarely signs international human rights conventions, but they have signed, ratified, acceded, and thereby become a “state party” to this one.

AG: As has Rwanda.

DK: Then I think it could be challenged under that treaty for starters, in a United States court because he has those rights under the covenant, but he also has rights as a US resident. I don’t fully know his status in the US but he has Constitutional protections as a legal resident, which I believe he could claim in any US courts.

AG: He has permanent resident status, and I think he was applying for citizenship.

DK: Then he has significant Constitutional rights, at least to all those rights that do not mention citizenship, but simply mention persons, and a lot of Constitutional rights are worded in that fashion. So I think he could bring a case here in the US to challenge his incarceration in Rwanda. That would be the best place to start, not only legally but also for political reasons, because that would be a case of great interest to people who know his story, whether it’s the movie version or his own more complex account.

AG: So you think his legal team should go to a US court to argue that he has been illegally extradited and that the US should demand his return.

DK: Yes. And of course the US has a lot of influence over the current government of Rwanda, so I think there could be a lot of power in that type of lawsuit. I’d bring it in the Ninth Circuit, which is in the West. More specifically, I’d bring it in California to make the point that he was the hero of the Hollywood movie “Hotel Rwanda,” and in hopes of getting some Hollywood interest in his case. Don Cheadle was nominated for an Oscar for playing him in the movie, and Paul consulted with him while it was being made. The movie was a great success, so I think Paul is owed support from people in Hollywood.

AG: That’s an interesting idea that hadn’t occurred to me. The George and Amal Clooney Foundation have, in collaboration with the American Bar Association’s International Human Rights Committee, said that they’re sending a monitor to make sure that Paul gets a fair trial in Rwanda, but you and I know it’s preposterous to think he will. So if they want to get serious, they need to support a challenge to his kidnapping and illegal rendition.

DK: Agreed.

AG: George Clooney’s activism in this part of the world has typically been consistent with US foreign policy objectives, most notably separating South Sudan from Sudan and getting former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir rendered to the International Criminal Court, which is commonly known as the International Caucasian Court for trying Africans.

However, Paul is a vastly more sympathetic character than Omar al-Bashir, so perhaps he will feel inclined to depart from longstanding US support for Rwandan President Paul Kagame and his totalitarian government.

DK: We can hope so. And if I were filing a complaint on Paul’s behalf, I would consider naming some key Rwandan officials, maybe even Paul Kagame himself, and you could do that because, while Kagame has some sovereign immunity, heads of state are typically not immune from a suit for an injunction.

That is to say, if you’re not asking for damages, you could bring a suit against Kagame to free Paul. You would have to get personal jurisdiction over him or some key Rwandan official, which could be done if you could serve them in the US while they were visiting here or something like that, which has been done before. There was a famous case of a Guatemalan military leader who was served with papers at his Harvard commencement for crimes he committed in Guatemala.

“If you’re not asking for damages, you could bring a suit against Kagame to free Paul.”

So I think that that would be the way to go. And, as you know, Kagame regularly comes to the US because he’s so close to various people in the US State Department and to former State Department personnel, people like Susan Rice and Samantha Power, who may be back in the State Department soon if Joe Biden is elected.

AG: Not to mention Ben Affleck. Kagame commonly visits Affleck on his trips to Boston, which is jarring if you consider Kagame’s crimes in Congo and Affleck’s charity, Eastern Congo Initiative , which describes itself as “U.S. based advocacy and grant-making initiative wholly focused on working with and for the people of eastern Congo.”

When not inhibited by the danger of contracting COVID-19, Kagame lives a celebrity lifestyle, jet-setting off to basketball games and international racing car events. The National Basketball Association (NBA) has been cluelessly making him the face of basketball’s growth in Africa.

He’s also on the university speaking circuit, and especially popular at fundamentalist Christian universities.

DK: He was in Pittsburgh just last year at Carnegie Mellon . If I were on his legal team—and I would be happy to serve on his legal team if asked—I would first file a complaint against the illegal extradition and then look into serving Kagame here. That would be a very powerful gesture.

AG: What about serving him when he comes to the UN?

DK: Well, he would have diplomatic immunity inside the walls of the UN, but not at the Trump Tower in UN Plaza, or the Hilton, or any other hotel or street in New York.

AG: Attorneys Peter Erlinder and Kurt Kerns managed to serve him in the US in a suit alleging crimes in the Rwandan Genocide and Congo Wars, but the Obama Administration requested immunity and brought out the heavy guns, including Bush administration War Crimes Ambassador Pierre Prosper, who has a history of supporting Kagame at the International Criminal Tribunal on Rwanda. Then the Supreme Court refused to review the case.

But this is a far simpler, less sweeping complaint about the persecution of one individual admired for saving lives in Rwanda in 1994.

DK: And kidnapping is a crime throughout the world. Again, you don’t have to look very hard to find international prohibitions on kidnapping. They include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights .

I would start by saying that the kidnapping violated Paul’s Constitutional rights. But then I would also say that it violated Paul’s rights under international law. I might be getting into the weeds here, but Congress has not passed implementing legislation on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, meaning you can’t actually go into the court and just sue under the covenant, but once you’re in court arguing for Paul’s Constitutional rights, you can cite the covenant as binding international law, giving you binding international rights.

Paul’s legal team might even think about the Alien Tort Claims Act as a means of getting injunctive relief ordering Rwanda to return him to the US.

AG: US courts have a long history of unjustly extraditing Rwandan exiles to Rwanda, notably including the cases of Professor Léopold Munyakazi and Pastor Elizaphan Ntakirutimana , but neither of those men were nearly so well-known and admired as Paul. Do you think Rwanda could have obtained a warrant for Paul in a proper extradition hearing?

DK: No, I don’t. I think Rwanda kidnapped Paul because they know that they lacked sufficient evidence that he had committed crimes in Rwanda, and no US court would have granted them a warrant to arrest him.

AG: Canadian lawyer John Philpot told me that he thought extradition treaties with the US and Rwanda might be relevant.

DK: I’m not familiar with extradition treaties between the US and Rwanda, but there may be some possibilities there. A lawsuit along the lines I mentioned, beginning with the violation of Paul’s Constitutional rights, could be done in tandem.

But in the end, look, this is a political case and political pressure needs to be brought to bear on Rwanda to free Paul, and a high profile lawsuit could help.

AG: I like your idea of filing the case in California because a Hollywood movie based on his story made him famous and caused a lot of Hollywood human rights activista to embrace him. It’s easy to find pictures of him with Angelina Jolie and, of course, Don Cheadle. Why else would you recommend filing in the Ninth Circuit?

DK: Well, at least historically, it’s been a bit more liberal. And again, I do think that the symbolism of bringing it in Los Angeles County would be helpful. The courts in Texas, where Paul is resident, are a little more conservative and possibly less sympathetic to him.

AG: What about the significance of him having been kidnapped in Dubai? Is it significant that he was kidnapped there instead of the US?

DK: This would have been far easier if he had been kidnapped in the US, but he would still have a viable claim because he’s a US resident being held against his will and unable to return to the US.

AG: He can’t even choose his own lawyers. They’ve assigned him Rwandan lawyers.

DK: That is also a violation of his Constitutional rights and his international rights under the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights.

AG: He’s also a Belgian citizen. His life was threatened there and he survived at least one assassination attempt when the car he was driving was hit and flipped over and he miraculously survived.

DK: Well that may be another good jurisdiction for him, maybe even better because he’s got citizenship there. That means he has all rights guaranteed to citizens by the Belgian Constitution, and Belgium also considers itself a place of universal jurisdiction. So that may be a great place to bring a case. At the very least it’s another option.

“Belgium also considers itself a place of universal jurisdiction.”

AG: Could cases conceivably be brought in both countries?

DK: If that were done, the courts would probably make a determination as to which court made most sense, and they would be consolidated in either Belgium or the US.

AG: Having observed quite a few of these trials, my guess is that it would be best to argue solely on the merits of the case within the law, and not mount a political trial based on Paul’s disagreements with Kagame about the Rwandan Genocide narrative and his crimes in DRC.

DK: I agree. It would be best not to raise those issues, which are irrelevant in this particular case. The key is to get him out and then he can continue to speak out for Rwandans and Congolese, as he has for many years now.

Challenging the genocide narrative would also be difficult because of how powerful it has become, ironically because of that movie.

AG: Again, I recommend that Black Agenda Report readers read your 2013 conversation with Paul in Counterpunch, Hotel Rwanda Revisited: an Interview with Paul Rusesabagina , where he says that the movie rightly depicted his effort to take a moral stand in “a sea of fire,” but that it also required the simplification of complex events and that the film’s producers wanted a happy Hollywood ending.

DK: I’m glad that’s relevant these many years later.

AG: What about the International Court of Justice? Any legal hope there?

DK: Well, the big problem with the International Court of Justice is that it’s reserved for disputes between states, so you would have to get the US or Belgium to bring a case against Rwanda. Paul could not just go into the International Court of justice on his own behalf.

The European Court of Human Rights does allow individuals to bring cases and there may be a similar court created by the African Union.

AG: There is—the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights —which is, for one, supposed to be an alternative to the International Criminal Court. However, Rwanda withdrew from that court’s jurisdiction after it ruled that Rwanda had violated political prisoner Victoire Ingabire’s rights.

DK: The European Court of Human Rights is the most vibrant of all those types of courts that I know of, but again, the problem would be jurisdictional. How does Europe have any jurisdiction over Rwanda or over Rwanda and its officials? I think, however, that if you could serve Paul Kagame in Europe, you might be able to get jurisdiction. You saw this happen with, for example, Augusto Pinochet.

AG: Is there anything else you’d like to say about this?

DK: Yes. This is a very important case for people who care about justice and human rights. Paul’s kidnapping is a huge miscarriage of justice against a man who has done a lot of good for Rwandans, Congolese, and people of the wider African Great Lakes region by speaking out and enlightening the rest of us willing to listen. He is also 66 years old and his health is challenged. This persecution should really anger people, and there has to be a political campaign, not just a legal case, to get him free.

_______________________________________________

Ann Garrison is an independent journalist based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She attended Stanford University and is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. In 2014 she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes region. She can be reached at @AnnGarrison, ann@kpfa.org, ann@anngarrison.com.

Ann Garrison is an independent journalist based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She attended Stanford University and is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. In 2014 she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes region. She can be reached at @AnnGarrison, ann@kpfa.org, ann@anngarrison.com.

Go to Original – blackagendareport.com

Tags: Africa, Genocide, Rwanda

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.