A Brief History of US Military Poisoning of Hawai’i

MILITARISM, 14 Dec 2020

Ann Wright, Kyle Kajihiro and Jim Albertini | Popular Resistance - TRANSCEND Media Service

7 Dec 2020 – Poisoning the Pacific: The US Military’s Secret Dumping of Plutonium, Chemical Weapons, and Agent Orange, a new book by Japan-based journalist Jon Mitchell, is a detailed investigation and documentation of U.S. and Japanese military chemical and biological poisoning and pollution across the Pacific, Asia and South East Asia. Mitchell’s work doesn’t cover the U.S. military poisoning of Hawai’i as that would require a separate volume due to the concentration of the U.S. military bases and their pollution in the state. But, his book of military poisons found in the rest of the Pacific is an excellent guide for an investigation into the pollution and contamination in and around the military bases in Hawai’i. This article is a start in that direction.

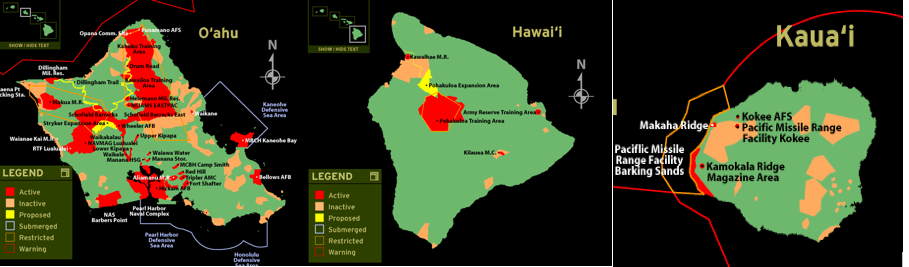

U.S. military contamination in Hawai’i comes from the many major military bases on four of the islands of Hawai’i. On Oahu the U.S. military bases include Pearl Harbor Naval Base, Hickam Air Force Base, Schofield Barracks Army Base, U.S. Army’s Fort Shafter, Tripler Army Hospital and Kaneohe Marine Base. The island of Kauai has the large Pacific Missile Test Facility. The Big Island of Hawai’i has the massive 130,000 acre firing range at Pohakuloa Training Area. The island of Kahoʻolawe is still contaminated from being bombed for decades. About 43,000 active duty members, 9,600 Guard and Reserve, 60,000 dependents and 20,000 military employees live in Hawai’i, mostly on Oahu. The military complex population of 132,600 comprises 10% of the 1.4 million population of the state.

Mitchell’s book begins with the World War II story of Japanese Unit 713 that developed chemical weapons on the Okinawan island of Okunashima and supervised their brutal, inhumane use in China during World War II. After the war ended, the U.S. gave immunity to the Japanese scientists and military medical officers responsible for the anthrax, botulism and supervised freezing to death of prisoners and allowed Japanese officials to go on to positions in prestigious medical and academic positions in Japan rather facing than prosecution as war criminals (as was done in Germany) in exchange for the data of the biological and chemical “experiments” done on tens of thousands Chinese.

While there were no experiments with anthrax in Hawai’i that we know of, there were other chemical and biological experiments with potentially lethal consequences conducted in the islands. On the Big Island of Hawai’i in the watershed of Hilo, the island’s largest town, in April and May 1967, in an experiment named “Red Oak Phase 1,” the U.S. Army detonated 155-mm artillery shells and 115-mm rocket warheads filled with deadly sarin gas in the dense rain forest of the Upper Waiakea Forest Reserve. Sarin, a highly toxic nerve agent is absorbed through the nose, mouth, eyes and, to a lesser extent, the skin, and can block breathing, dim vision and, in sufficient doses, bring on coma and death. While the U.S. military claims that the sarin gas was away from populated areas and would not be a danger to people, 53 years later, hunters are hesitant to go into that part of the forest reserve as nothing grows there according to long time Big Island resident Jim Albertini. A wide range of chemical and biological weapons were tested in the Waiakea forest.

In the 1960s, in a project called Shipboard Hazard and Defense or SHAD, the U.S. military conducted six tests in the Pacific using nerve or chemical agents that were sprayed on ships and their crews to determine how quickly the poisons could be detected and how rapidly they would disperse, as well as to test the effectiveness of protective gear and decontamination procedures in use at the time. Of the six tests, three used sarin, a nerve agent, or VX, a nerve gas; one used staphylococcal enterotoxin B, known as SEB, a biological toxin; one used a simulant believed to be harmless but subsequently found to be dangerous; and one used a nonpoisonous simulant.

The SHAD tests were a part of 134 biological and chemical warfare vulnerability tests from 1962 to 1973 planned by the Department of Defense’s Deseret Test Center in Fort Douglas, Utah. The Project 112 and Project SHAD tests consisted of both land-based and sea-based tests at different locations, including at least six in Hawai’i.

One of these tests, a test named Flower Drum Phase I, was conducted in 1964 off the coast of Hawaii, which involved spraying sarin gas and a chemical simulant onto the George Eastman, a Navy cargo ship and into its ventilation system while the crew wore various levels of protective gear. In phase 2 of the test, VX gas was sprayed onto a barge to examine the ship’s water wash-down system and other decontamination measures.

In August and September 1965, a test named ”Fearless Johnny” was carried out southwest of Honolulu in which the George Eastman and her crew were sprayed again, this time with VX nerve agent and a simulant to ”evaluate the magnitude of exterior and interior contamination levels” and to study ”the shipboard wash-down system.” VX gas, like all nerve agents, penetrates the skin or lungs to disrupt the body’s nervous system and stop breathing. In small quantities, exposure causes death.

Additionally, in 1965, in an operation named “Big Tom,” the U.S. military sprayed bacteria over Oahu to simulate a biological attack. The test used Bacillus globigii, a bacterium believed at the time to be harmless but researchers later discovered it was a relative of the bacterium that causes anthrax and could cause infections in people with weakened immune systems.

In April and May 1966, bacillus globigii was again used in Hawaii when it was exploded from bomblets. From April to June 1969, another experiment Deseret Test Center Test 69-32, was conducted southwest of Oahu, when a U.S. Air Force F-4 Phantom jet sprayed five Navy tugboats with Serratia marcescens and Escherichia coli, two germs that were thought to be harmless but Serratia marcescens in time turned out to be dangerous.

In another part of the Pacific, in September and October 1968 in the Marshall Islands, Deseret Test Center Test 68-50, was intended to determine the casualty levels from an F-4 Phantom jet spraying SEB, a crippling germ toxin. The jet sprayed the mist over part of Eniwetok Atoll and five Army light tugs. SEB is an incapacitating agent that can knock out people for one or two weeks with fever, chills, headache and coughing. The SEB came from a bacteria that causes a common type of food poisoning.

DoD Investigators identified 5,842 U.S. military who were involved in one or more of these tests. Civilians living in areas where the tests took place were not notified of the tests.

Veterans who have health concerns regarding their participation these experiments could contact the VA’s Helpline toll (800) 749-8387, but civilians cannot use the VA contact even though they may have been injured by the same experiments.

Mitchell’s book continues with the horrific human consequences of the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the trail of poison and pollution from the past 75 years after World War II from U.S. military bases on Okinawa, Japan, Guam, South Korea, Johnston Island, the Philippines and from the nuclear testing contamination on the Marshall Islands.

Extraordinarily researched and documented by more than 12,000 pages of documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) over the past two decades, Mitchell’s describes Okinawa, an island he has visited many times as an investigative journalist, as “The Junk Heap of the Pacific” for all the munitions and equipment that the U.S. military buried and dumped at sea from the more than 30 U.S. military bases located on the small island, which contains over 70 percent of all U.S. military bases in Japan.

But, Okinawa was not the only “Junk Heap” in the Pacific. In Hawai’i, according the 2007 Congressional Research report “U.S. Disposal of Chemical Weapons in the Ocean: Background and Issues for Congress,” over the decades since World War II, the U.S. military has dumped tens of thousands of bombs, some filled with deadly chemicals, off Oahu, all of which still could be accidently dredged up.

In 1944, 4,220 tons of unspecified toxics and hydrogen cyanide and approximately 16,000 M47A2 100-pound mustard bombs were dumped about five miles off Pearl Harbor. From October 17- November 2, 1945, 20 M79 1000-pound hydrogen cyanide bombs 1,100 M79 1000-pound cyanogen chloride bombs, 125 M78 500-pound cyanogen chloride bombs, 14,956 M70 114-pound mustard bombs, and 30,917 4.2-inch mortar mustard shells were dumped off Waianae, the west coast of Oahu.

From 1964-1978, 2189 steel drums of radioactive waste, including clothing, tools and other materials contaminated from radioactive nuclear refueling of nuclear submarines at Pearl Harbor, were dumped 55 miles off Oahu. During this period 4,843,000 gallons of low-level radioactive waste liquid was discharged into Pearl Harbor.

A 2016 Department of Defense study for the U.S. Congress entitled “Research Related to Effect of Ocean Disposal of Munitions in U.S. Coastal Waters” surveyed Ordnance Reef and the Hawaii Undersea Military Munitions Assessment (HUMMA) Study Site which are both off the island of Oahu.

Ordnance Reef is located from the shoreline to approximately 1.5 nautical miles off Oahu’s Waianae coast and contains conventional sea-disposed munitions at depths from 30 to over 300 feet. Because a number of sea-disposed munitions at Ordnance Reef are at depths less than 120 feet, this area is considered a shallow-water site. The nearby shore property is used for residential and recreational purposes with maritime recreational activities and subsistence fishing just off-shore.

Fishers and divers who use the 120-foot shallow waters of Waianae on the west coast of Oahu are probably not reassured by the DOD conclusion that the munitions do not pose significant harm and that the health effects appear to be minimal.

The HUMMA Study Site is located approximately five miles south of Pearl Harbor in waters in excess of 900 feet deep. Based on vague historical records, the Army believed this site potentially contains sea-disposed chemical warfare material such as chemical munitions or bulk containers of chemical agents. As a result, the researchers designed their research effort to investigate both conventional and chemical munitions.

The study concluded that “sea-disposed munitions, which have become part of the ocean environment and also provide critical habitat to marine life, do not pose significant harm when left in place; removing or cleaning up munitions sea-disposal sites would have more serious effects on marine life and the ocean environment than would leaving them in place; and the potential health effects from sea-disposed munitions in U.S. coastal waters appear to be minimal.”

Mitchell’s heart-wrenching details of the U.S. chemical attack on Viet Nam, Laos and Cambodia as it sprayed millions of gallons of cancer-causing chemical agents, including Agent Orange, on local populations and the huge amounts the chemical agents the U.S. left on Okinawa and Guam are almost beyond belief. Millions of Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians were killed or disabled by these chemicals as were thousands of U.S. military service members and their offspring who came into contact with the chemicals during the war on Viet Nam.

In Hawai’i, the University of Hawai’i has acknowledged extensive testing of Agent Orange on behalf of the Department of Defense with mixtures of Agent Orange on Kauai Island at the Kauai Agriculture Research Station in 1967–68 and on Hawaii Island in 1966. In 1997, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Hawai’i state Department of Health discovered that the University of Hawai’i had failed to dispose properly of these hazardous materials and fined the University $1.8 million for violations in Kauai and on the island of Hawai’i. In April 2000, barrels of these materials were finally shipped out of the state.

In the chapter titled “Toxic Territories: Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas and Johnston Island” Mitchell describes the ongoing challenge brought by the U.S. militarization of Guam and the Northern Marianas. He identifies environmental degradation from U.S. nuclear ships and submarines discharging radioactive contaminated coolant water from leaks in their nuclear propulsion systems and the use of Agent Orange as a defoliant on the three major military bases.

In 2012, the EPA removed approximately 320 TONS of soil contaminated by PCBs from a military pump station on Guam when the U.S. military refused to take responsibility for it. Mitchell also details the dramatic increase in the number of U.S. military on the island with the transfer of 5,000 Marines and tens of thousands of family members from Okinawa to a new base on Guam without an increase in off-base infrastructure. This has resulted in a dramatic increase pressure on the water table used by everyone on Guam and has impacted daily life on Guam with increased road usage by the increase in population. These issues have mobilized substantial citizen activism on Guam challenging the increased militarization of the small U.S. territory that has a population of only 169,500.

In Hawai’i, military contamination hazards, such as unexploded ordnance,14 various types of fuels and petroleum products; organic solvents such as perchloroethylene and trichloroethylene; dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB); explosives and propellants such as cyclotrimethylenetrin-itramine (RDX), trinitrotoluene (TNT), octogen (HMX) and perchlorate; heavy metals such as lead and mercury; napalm, chemical weapons, and radioactive waste from nuclear powered ships, and Cobalt 60, a radioactive waste product from nuclear powered ships, have been found in sediment at the massive naval base Pearl Harbor, near Honolulu, the island of Oahu’s largest city and the capital of the state.

Potentially deadly nuclear accidents have occurred in and near Hawai’i. In 1960, there was a fire aboard the nuclear-powered submarine USS Sargo (SSN 583) in Pearl Harbor, killing one crew member. The captain submerged the sub and flooded it to put out the fire which prevented a possible nuclear meltdown.

However, Hawai’i does not escape Mitchell’s reminder of U.S. Navy nuclear powered vessel operations some of which have been riddled with carelessness and have resulted in deadly collisions including three in 2017. Even earlier, in February 2001, the Ehime Maru, a Japanese prefecture fishery high-school training ship, was departing from Honolulu and was sailing off the coast of Oahu when a nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Greeneville, suddenly surfaced directly beneath the Ehime Maru breaking her hull and sinking the ship. Nine on ship, including four teenage students, died in the collision. Among the reasons for the collision was the distracting presence of civilian VIPs aboard the submarine, two of whom were negligently allowed to operate the system that surfaced the submarine beneath the Ehime Maru. The submarine’s commanding officer only received a minor punishment. Senior flag officer retired Admiral Richard Macke had arranged the VIP trip. Mitchell writes that Macke had lost a previous job for his comments following the 1995 gang rape on Okinawa.

Mitchell alerts us that the stationing of nuclear aircraft carriers and submarines at the mouth of Tokyo Bay is “a disaster waiting to happen.” The distance between the bottom of the hulls of these vessels and the seabed in the bay is very small and a massive earthquake such as the magnitude 9.0 Tohoku earthquake and the resulting tsunami could leave nuclear aircraft carriers and submarines high and dry disabling the nuclear reactors cooling systems and igniting fires in the nuclear reactors that could send plumes of highly enriched uranium—”far more toxic than that of Fukushima Daiichi”—across Tokyo Bay and into the densely populated city of Tokyo.

This bit of information should make us in Hawai’i ask, “How deep is Pearl Harbor and what is in the West Loch munitions storage facilities and could a tsunami have the same results here”? The current proposed expansion of the West Loch munitions facilities and lack of information of what type of munitions would be stored from the U.S. military has created community concerns in the suburban areas that now surround the West Loch area which was built during World War II when few people lived in the area. Construction is slated to begin in 2022 on the 62-acre site would include 35 earth-covered reinforced concrete storage magazines and operational support facilities within the 4,092 acre West Loch ammunition depot.

In a nearby Pacific area, from 1958-1963, the U.S. exploded 12 US nuclear weapons in the atmosphere on Johnston Island, 700 miles south of Hawai’i. A 1962 atmospheric thermonuclear blast produced a fireball visible in Honolulu, where it knocked out traffic lights. Two nuclear weapons blew up on the launch pad and plutonium from the bombs was bulldozed into the lagoon. Johnston Island was also the site of chemical weapon storage and burning on an industrial level. A large toxic pit of debris covered in dirt remains on the island with a sign “Wildlife Refuge.” The island has been hit with severe storms in recent years and currents can transport military toxins from Johnston Island to Hawaii and around the Pacific.

Mitchell’s main observation about military contamination in Hawai’i is in a single, long paragraph: “Crossing the Pacific Ocean, we arrive at Hawaii, home to approximately 142 military properties and multiple polluted sites. At its Pearl Harbor Naval Complex, contamination has emanated from underground fuel tanks, dry cleaners, and spills from electrical transformers containing cancer-causing polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).”

Mitchell continued in his important book, “In 2014, one hundred thousand liters (24,000 gallons) of jet fuel spilled from the navy’s storage tanks at Red Hill, Honolulu. On Kaneohe Marine Corps Base, more than a thousand homes were built on land polluted with high levels of pesticides; residents had not been warned of the dangers. In the military, families are housed in moldy, lead-painted, radon-emitting properties that if used for civilian tenants, landlords would be punished for multiple health code violations.”

The twenty massive 20 story fuel tanks dug 75 years ago into the hillside of Red Hill located above Pearl Harbor hold 250 million gallons of jet fuel. These ancient leaking tanks are only 100 feet above the drinking water aquifer of Honolulu and have been a source of citizen concern for decades. Underground jet fuel tanks in California and the State of Washington have been closed down, but the U.S. Navy refuses to consider shutting down the 20 tanks despite the danger to Honolulu’s water supply.

Not only does jet fuel leak into Honolulu’s drinking water aquifer, but PFAS (per- and poly fluoroalkyl substances) used in firefighting foams on Air Force bases contaminate the seafood taken from surrounding waters. The toxic foams have been allowed to seep into the ground and surface water to poison aquatic life. One variety of PFAS, known as PFOS (Perfluoro Octane Sulfonic Acid) present in aircraft firefighting foams, is the most toxic of all 6,000 or so PFAS chemicals on the market. PFOS is linked to a host of cancers, fetal abnormalities, and childhood diseases. PFOS is bio-accumulative in fish and other seafood. Just one part per trillion is enough to trigger a bio-accumulative process in seafood that is a danger to human health.

According to a March 2018 study by the Pentagon, the water at or around at least 126 military installations contains potentially harmful levels of perfluorinated compounds. However, the Environment Working Group has identified 175 military installations and sites nationwide that are known to be contaminated by PFAS, including 44 civilian airports that are also used by Air National Guard units.

No military bases in Hawai’i are listed in the study, but the community should be alert for possible PFAS contamination in the future in areas around Hickam Air Base, Pearl Harbor Naval Base, Wheeler Airfield, Kaneohe Marine Air Station and the Pohakuloa Airfield.

In March 2020 the Secretary of Defense issued a policy requiring all DoD-owned water systems, where DoD supplies drinking water to the installation, to test for PFAS, at installations world-wide, using the most recent U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) test method. The quarterly EPA report on Joint Base Hickam-Pearl Harbor is here.

Other information on contamination at military sites over the years is documented in Propublica’s report “Bombs in your Backyard”.

Radioactive materials were brought into Hawai’i by the U.S. military. Depleted uranium, a radioactive heavy metal, was used in aiming rounds for the Davy Crockett, a 1960s nuclear device intended as a last-ditch weapon against masses of Soviet soldiers in the event of war. A military shipping list showed 298 pounds of deplete uranium were sent to Hawai’i in 714 spotting rounds for the Davy Crockett between 1962 and 1968. The 7-inch aiming rounds were launched by a gas piston which was attached to a recoilless rifle that could fire a 76-pound nuclear bomb. The aiming rounds were fired at Schofield Barracks Army base on Oahu and in 1994, two DU rounds were accidentally fired by the USS Lake Erie while the ship was in Pearl Harbor. The rounds went up into the Koʻolau mountains above the Honolulu suburb of ʻAiea and were never recovered.

An unknown number of depleted uranium rounds were also fired at the 130,000 acre Pohakuloa Training Area (PTA), located at 6,000 feet on the plateau between the Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa volcanos on the Big Island of Hawai’i. On June 13, 2017, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) denied a hearing request about radiation dangers of inhaling Depleted Uranium (DU) oxide dust particles dispersed by winds and high explosives at Pohakuloa. Remarkably, the NRC ruled that citizens that could be affected by the DU had “No Standing.” Citizen radiation monitors, on numerous occasions, had detected radiation levels 3-4 times background levels in public areas around PTA. However, the U.S. military claims there is no danger from DU particles remaining.

The U.S. Army calls Pohakuloa Training Area the “Pacific’s premier training area” with a 51,000-acre “impact area,” that is used by Hawaii-based and visiting international military forces. It is the largest live-fire range in Hawaii and supports full-scale combined arms field training from the squad to brigade (approximately 3,500 soldiers) level. Hundreds of thousands of munitions including from small weapons as well as artillery and large bombs dropped by B-52s and other bombers flown from the mainland of the U.S. and Guam have been fired into the earth at PTA for over 75 years since World War II. In 2019, in response to a lawsuit brought by Hawai’i elders on the use of 23,000 acres of State land in the training area, the Hawai’i Supreme Court said the State of Hawai’i has a duty to “mālama ʻāina,” called two Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) inspection reports “grossly inadequate” and ordered the state to develop and potentially execute a plan to obtain adequate funding for a comprehensive cleanup of the land.

The Hawaiian island of Kaho’olawe was used for U.S. military bombing practice for 49 years from 1941 until 1990 during World War II, the Korean War and the war on Viet Nam. A huge quantity of artillery, bombs, missiles and torpedoes were fired into the island, including three massive 500-ton TNT explosions named “Sailor’s Hat” to test the simulated nuclear blast effects on ships. The explosions created a crater in the lava which filled in with brackish water. The Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana, a Native Hawaiian group that formed in 1976, employed non-violent direct action, lawsuits, and political pressure, to end the bombing in 1990 and secured the return of the island to the State of Hawaiʻi as a Native Hawaiian cultural reserve in 2003. After $400 million spent on clean-up, Kahoʻolawe is still widely contaminated with unexploded ordnance (UXO) buried in the ground and in nearshore waters.

This article identifies many of the poisons caused by the U.S. military in Hawai’i. As residents of Hawai’i, the home of the headquarters of the Indo-Pacific Command, the U.S. military command responsible for U.S. military operations in Asia and the Pacific, we should know about the poisoning and pollution that has been caused for decades by units under its command.

We should listen to the students at the University of Hawai’i, Hawai’i Pacific University and the East-West Center who come from many of the polluted and poisoned islands and countries who can provide testimony to the levels of pollution in their lands. No doubt the senior military officers and civilian defense officials from countries all over Asia and the Pacific who attend the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, the U.S. military’s regional military educational institution which is located in Waikiki, could confirm the poisons and pollution identified by Mitchell in his book, and perhaps add even more.

_________________________________________________

Ann Wright served 29 years in the U.S. Army/Army Reserves and retired as a Colonel. She was a U.S. diplomat for 16 years and following her resignation from the U.S. government in 2003 in opposition to the U.S. war on Iraq, she has lived in Honolulu for 17 years. She is the co-author of “Dissent: Voices of Conscience.”

Ann Wright served 29 years in the U.S. Army/Army Reserves and retired as a Colonel. She was a U.S. diplomat for 16 years and following her resignation from the U.S. government in 2003 in opposition to the U.S. war on Iraq, she has lived in Honolulu for 17 years. She is the co-author of “Dissent: Voices of Conscience.”

Kyle Kajihiro has researched the militarization of Hawai’i for decades and received his Ph.D. from the University of Hawai’i in 2020 with a dissertation titled “Kahoʻolawe Is Not An Island: Political-Ecological Assemblages, Spaces of Indigenous (Re)Emergence, and the Logic of Counterinsurgency.” He is a lecturer in the Department of Geography and Environment and Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa and is the former Hawai’i Area Program Director of the American Friends Service Committee.

Kyle Kajihiro has researched the militarization of Hawai’i for decades and received his Ph.D. from the University of Hawai’i in 2020 with a dissertation titled “Kahoʻolawe Is Not An Island: Political-Ecological Assemblages, Spaces of Indigenous (Re)Emergence, and the Logic of Counterinsurgency.” He is a lecturer in the Department of Geography and Environment and Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa and is the former Hawai’i Area Program Director of the American Friends Service Committee.

Jim Albertini is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment, a former Catholic School teacher, and long-time social justice activist since the US war on Vietnam. He has done research on the use of depleted uranium at Pohakuloa Military Training Area and is the author of “The Dark Side of Paradise: Hawai’i in a Nuclear World.” Jim is the founder and director of Malu ‘Aina Center for Non-violent Education & Action, a spiritual community based on peace, justice and sustainable organic farming on Big Island, Hawai’i – P.O. Box 489 Ola’a (Kurtistown), Hawai’i 96760. Phone (+ 808) 966-7622 Email: ja@malu-aina.org – website: malu-aina.org

Jim Albertini is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment, a former Catholic School teacher, and long-time social justice activist since the US war on Vietnam. He has done research on the use of depleted uranium at Pohakuloa Military Training Area and is the author of “The Dark Side of Paradise: Hawai’i in a Nuclear World.” Jim is the founder and director of Malu ‘Aina Center for Non-violent Education & Action, a spiritual community based on peace, justice and sustainable organic farming on Big Island, Hawai’i – P.O. Box 489 Ola’a (Kurtistown), Hawai’i 96760. Phone (+ 808) 966-7622 Email: ja@malu-aina.org – website: malu-aina.org

Go to Original – popularresistance.org

Tags: Anglo America, Arms Industry, Arms Race, Conflict, Geopolitics, Hawaii, Hawaiian Culture, Hegemony, History, Human Rights, Imperialism, International Relations, Invasion, Military, Military Industrial Complex, Military Intervention, Military Supremacy, NATO, Occupation, Politics, Power, US Military, USA, Violence, War, War on Terror, West, World

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.