While in her 20s in New York City, Day got an abortion for a pregnancy conceived during an ill-fated relationship, from an ex-boyfriend of anarchist Emma Goldman, which she wrote about in a semi-autobiographical work of fiction called The Eleventh Virgin. Soon after, she also went through a divorce. She also reflected on these choices, which flew in the face of established church doctrine, in her extensive non-fiction writing. Day’s complicated relationship with her faith endured as she aged, and by her late life, she became a dogmatic follower of church rules. “Religion for her had to be life-transforming and disruptive of your life if it was going to mean anything,” says Loughery.

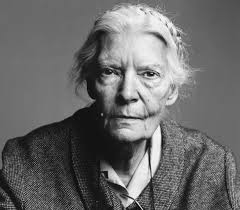

Dorothy Day in 1916 – Wikipedia

Day sought to force the church to be accountable to living in Christ’s name, focusing on the marginalized and anti-poverty work, instead of on specific practices like abortion. Ultimately, Day committed herself fully to Catholicism as an organizing principle for her political beliefs. In 1933, during the height of the Great Depression, Day founded the Catholic Worker Movement, with Peter Maurin, with the release of their first periodical, sold for a penny (which is still in circulation, still for a penny). Day began to open Catholic Worker “houses of hospitality,” maintained completely by volunteers, which sought to provide food, shelter, clothing, and any other needed resources for those impacted by poverty. Their practice was to refuse no one.

“If we are thinking in terms of personal responsibility, to those who sit around and say, ‘Why don’t the priests do this or that?’ or ‘Why don’t they [that indefinite they] do this or that?’ we should reply, ‘Why don’t we all?’” Day wrote in Commonweal magazine, in 1938.

While the Catholic Worker houses were practicing direct service, Day made clear that structural injustices must also be fought. In addition to providing immediate relief to those suffering, the Catholic Worker houses were a space for activism. In the 1950s, Day and other anti-war protesters organized against civilian drills during the Cold War. “We will not obey this order to pretend, to evacuate, to hide,” read the pamphlet distributed by Catholic Worker activists. “In view of the certain knowledge the administration of this country has that there is no defense in atomic warfare, we know this drill to be a military act in a cold war to instill fear, to prepare the collective mind for war.”

Throughout her life, Day lent her support and voice to a variety of social movements, including joining Cesar Chavez’s labor strikes on behalf of California farmworkers in 1973 at age 76. She was arrested and jailed for her civil disobedience.

To this day, Catholic Worker houses across America remain engaged in the social activism that Dorothy Day promoted throughout her life. In 2019, the Iowa City Catholic Worker house provided asylum-seekers with safe harbor after working for their release from immigration detention. Day’s influence is seen within the broader Catholic social justice community. One of Day’s granddaughters, Martha Hennessy, 65, was sentenced to prison on November 13 for her involvement with the Kings Bay Plowshares 7, a group of Catholic pacifists and Catholic Worker members that broke into a naval base in 2018 in protest of its stockpile of nuclear weapons.

And as mutual aid organizing has swept the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic, these community-oriented support systems carry on the tradition Day promoted of taking direct responsibility for other humans. “[Day believed] government programs, while they might be necessary and very useful, they’re not a substitute for the dignity that she was saying was essential for humans to give to one another,” says sociologist Sharon Erickson Nepstad, author of Catholic Social Activism: Progressive Movements in the United States.

“[Day] looked upon American society as a monumentally ego-driven society…. Most of her life was spent in trying to figure out how to get away from that sense of ego,” says Loughery.

In 2015, Pope Francis mentioned Day in a speech, which popularized the campaign for her sainthood, which Day herself may have resisted. “What we know about [Martin Luther King Jr.], once he became a civil saint, people began using his life and his legacy for purposes that aren’t always in line with what he advocated,” says Nepstad. “I think one of the reasons that she’s so appealing to many people is precisely because of her humanity, not her sainthood. She was someone who had a history that didn’t fit neatly within the Catholic Church, and was someone who I think demonstrated the value of being both really committed to ideals, but always embracing critical thinking.”

Go to Original – teenvogue.com