Vincent van Gogh on Art and the Power of Love in Letters to His Brother

INSPIRATIONAL, 14 Dec 2020

Maria Popova | Brain Pickings – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Whosoever loves much performs much, and can accomplish much, and what is done in love is well done!”

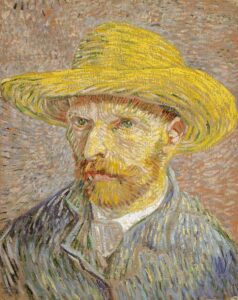

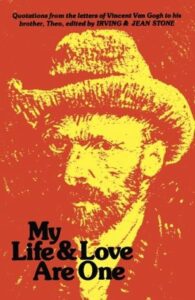

“You can only go with loves in this life,” Ray Bradbury memorably proclaimed. Whether love be bewitching or tormenting, whether pondered by the poets or scrutinized by the scientists, one thing is for certain — it is art’s most powerful and enduring muse, fuel for the creative process more potent than anything the world has known. A poignant testament to this, and a fine addition to history’s most beautiful reflections on love, comes from the visionary Vincent van Gogh (March 30, 1853–July 29, 1890) in My Life & Love Are One (public library) — a slim 1976 treasure that traces “the magic and melancholy of Vincent van Gogh” by culling his thoughts on love, art, and turmoil from his letters to his brother Theo, which were originally published in 1937 as the hefty tome Dear Theo: The Autobiography of Vincent van Gogh. The title comes from a specific letter written during one of the painter’s periods of respite from mental illness, in which he professes to his brother: “Life has become very dear to me, and I am very glad that I love. My life and my love are one.”

“You can only go with loves in this life,” Ray Bradbury memorably proclaimed. Whether love be bewitching or tormenting, whether pondered by the poets or scrutinized by the scientists, one thing is for certain — it is art’s most powerful and enduring muse, fuel for the creative process more potent than anything the world has known. A poignant testament to this, and a fine addition to history’s most beautiful reflections on love, comes from the visionary Vincent van Gogh (March 30, 1853–July 29, 1890) in My Life & Love Are One (public library) — a slim 1976 treasure that traces “the magic and melancholy of Vincent van Gogh” by culling his thoughts on love, art, and turmoil from his letters to his brother Theo, which were originally published in 1937 as the hefty tome Dear Theo: The Autobiography of Vincent van Gogh. The title comes from a specific letter written during one of the painter’s periods of respite from mental illness, in which he professes to his brother: “Life has become very dear to me, and I am very glad that I love. My life and my love are one.”

In one letter, Van Gogh extols the grounding, self-soothing quality of love’s intrinsic wisdom:

Everyone who works with love and with intelligence finds in the very sincerity of his love for nature and art a kind of armor against the opinions of other people.

It was certainly an armor he needed — he lived his life in poverty, and the residents of the town where he settled in his final years petitioned to have him evicted from the artist commune he shared with Paul Gauguin and two other artists, on account of his madness. He soon moved into an asylum, where he continued to paint. Another letter to Theo rings with the paradoxical poignancy of desperation and resilience:

What am I in the eyes of most people? A good-for-nothing, an eccentric and disagreeable man, somebody who has no position in society and never will have. Very well, even if that were true, I should want to show by my work what there is in the heart of such an eccentric man, of such a nobody.

And what a heart it was. In a different letter, Vincent relays to Theo the consciousness-expanding capacity of love — which Kierkegaard so eloquently captured — at the dawn of a new love affair:

Since the beginning of this love I have felt that unless I gave myself up to it entirely, without any restriction, with all my heart, there was no chance for me whatever, and even so my chance is slight. But what is it to me whether my chance is slight or great? I mean, must I consider this when I love? No, no reckoning; one loves because one loves. Then we keep our heads clear, and do not cloud our minds, nor do we hide our feelings, nor smother the fire and light, but simply say: Thank God, I love.

To be sure, Van Gogh has the prudence to recognize that friendship is at least as great a gift as romantic love. In another letter, he tells Theo:

Do you know what frees one from this captivity? It is every deep serious affection. Being friends, being brothers, love, these open the prison by supreme power, by some magic force. Where sympathy is renewed, life is restored.

And in another still:

Love a friend, love a wife, something, whatever you like, but one must love with a lofty and serious intimate sympathy, with strength, with intelligence, and one must always try to know deeper, better, and more.

This all-inclusive approach to love — this casting of a wide net of affections — is something Van Gogh believed wholeheartedly, and something Ray Bradbury would come to echo a century and a half later in telling aspiring writers, “I want your loves to be multiple.” Vincent writes to Theo:

It is good to love many things, for therein lies the true strength, and whosoever loves much performs much, and can accomplish much, and what is done in love is well done!

And later:

The best way to know God is to love many things.

Van Gogh sees the human capacity for love as integral to the creative process:

In order to work and to become an artist one needs love. At least, one who wants sentiment in his work must in the first place feel it himself, and live with his heart.

Indeed, it is this capacity for love — for living from one’s heart — that sustains the artist through struggle and rejection. In another letter, Van Gogh writes:

I believe more and more that to work for the sake of the work is the principle of all great artists: not to be discouraged even though almost starving, and though one feels one has to say farewell to all material comfort.

For Van Gogh, this heart-first approach to art and life was the root of all that is worthy. In another letter to Theo, he articulates what might well be his deepest underlying credo:

Do you know that it is very, very necessary for honest people to remain in art? Hardly anyone knows that the secret of beautiful work lies to a great extent in truth and sincere sentiment.

Though long out of print, surviving copies of My Life & Love Are One are still findable and very much worth the hunt. Complement it with a peek inside Van Gogh’s never-before-revealed sketchbooks, then revisit Susan Sontag on love.

_______________________________________

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors. Email: brainpicker@brainpickings.org

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors. Email: brainpicker@brainpickings.org

Go to Original – brainpickings.org

Tags: Art, Inspirational, Psychology, Vincent Van Gogh

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.