Brazilian Butt Lift: Behind the World’s Most Dangerous Cosmetic Surgery

IN FOCUS, 15 Feb 2021

Sophie Elmirst | The Guardian - TRANSCEND Media Service

The BBL is the fastest growing cosmetic surgery in the world, despite the mounting number of deaths resulting from the procedure. What is driving its astonishing rise?

9 Feb 2021 – The quest was simple: Melissa wanted the perfect bottom. In her mind, it resembled a plump, ripe peach, like the emoji. She was already halfway there. In 2018, she’d had a Brazilian butt lift, known as a BBL, a surgical procedure in which fat is removed from various parts of the body and then injected back into the buttocks. Melissa’s bottom was already rounder and fuller than before, and she was delighted by the effect, with how it made her feel and how it made her look. But it could be better. It could always be better.

On a recent afternoon, Melissa visited the British aesthetic surgeon Dr Lucy Glancey for a consultation. Glancey had performed Melissa’s first BBL at her clinic on the Essex-Suffolk borders, a suite of rooms boasting shining white cupboards, a full-length mirror and drawers stuffed with syringes. As she waited for Melissa to arrive, Glancey showed me a picture of Melissa on the beach in Dubai, wearing a palm-print bikini and posing in a kind of provocative crouch – arms, breasts, thighs and buttocks all arranged for optimum effect. “Look how good she looks,” said Glancey, admiring Melissa and her own work. “I said to her, I don’t see what else we can do.”

When Melissa walked into the room, she didn’t exactly resemble her digital self, but then, who does? She’d swapped Dubai-luxe for Suffolk-casual – blue jeans and a pink sweater. After a quick chat, Glancey – dark blue scrubs, coral toenails – asked Melissa to take off her clothes. Together, doctor and patient stood in front of the mirror and stared.

“OK,” said Glancey. “Which side do you prefer?”

“This side,” said Melissa, indicating her left flank.

Glancey proceeded to work her way round Melissa’s figure, considering its contours with bracing candour.

“You’ve kind of gained here,” she said, pointing at Melissa’s midriff.

“But here,” said Melissa, pressing the dip she could see in her right buttock, a flaw she’d noticed while on holiday. “Can you see?”

Like anyone inspecting their own body, Melissa could see things no one else could see. She wasn’t seeing just its current form in the mirror, but multiple versions: her former body, her desired body, her digital body. In her teens, nearly a decade ago, when Cara Delevingne’s thigh gap had its own Twitter account, Melissa had wanted to be thin and flat like everyone else. Then fashions changed. Explaining why she got her first BBL, Melissa, who is white, said she had wanted to fill out a pair of jeans and appeal to the kind of men she liked. “I felt attracted to black men and mixed-race men, and they liked curvier women,” she told me.

The surgery, which can cost up to £8,000, also helps her earning potential. Most of the time, Melissa works in a gym, but she also makes money on the side modelling clothes on Instagram. “When you’re looking at what gets the most attention and what gets the most likes, they’re always girls of this shape,” she said.

Melissa’s digital body, enhanced by the photo-editing app Facetune, acts as a kind of blueprint for her future physical body. She told me that her friends sometimes edit their pictures on dating apps to the point where they’re unable to meet up with anyone, as the version of themselves they’ve advertised is too far removed from reality. “If you’ve had a BBL, it’s like you’ve already edited your body in real life,” Melissa said, “so you don’t have to edit your pictures.”

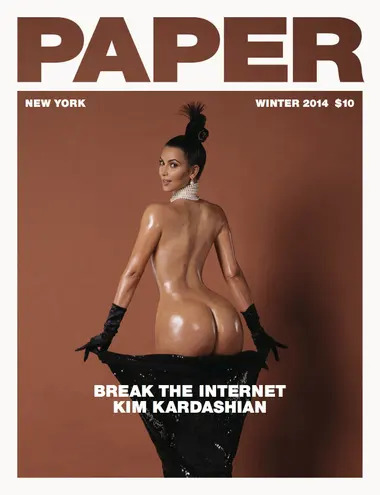

A decade ago, Glancey rarely performed BBLs. Now, in the course of a week, she does two or three and receives about 30 inquiries. Since 2015, the number of butt lifts performed globally has grown by 77.6%, according to a recent survey by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. It is the fastest-growing cosmetic surgery in the world. When Glancey scrolls through Instagram, she sees it everywhere: beach-ball buttocks mimicking the most famous bottom in the world, a bottom so scrutinised, so emulated, so monetised, that it no longer feels like a body part, but its own high-concept venture, its own startup turned major IPO. (It will probably sue me.) The popularity of the BBL, Glancey told me, is down to one woman: “Her impact,” she said of Kim Kardashian West, “really is her body.”

Dr Mark Mofid, a leading American BBL surgeon, also noted the influence of Jennifer Lopez and Nicki Minaj, alongside a glut of imagery on social media that “had really popularised the beauty of feminine curves”. But achieving such beauty can be risky. In 2017, Mofid published a paper in the Aesthetic Surgery Journal which revealed that 3% of the 692 surgeons he had surveyed had experienced the death of a patient after performing the surgery. Overall, one in 3,000 BBLs resulted in death, making it the world’s most dangerous cosmetic procedure.

From left: Melissa Kerr, Abimbola Ajoke Bamgbos and Leah Cambridge, who all died as a result of having BBL surgery.

Photograph: Various

In the past three years, three British women – Abimbola Ajoke Bamgbose, Leah Cambridge and Melissa Kerr – have died as a result of complications arising from BBLs in Turkey, the most popular destination for UK patients seeking cheaper aesthetic surgery. Elsewhere, there have been many others: Joselyn Cano in Colombia, Gia Romualdo-Rodriguez, Heather Meadows, Ranika Hall and Danea Plasencia in Miami. According to local reports, in recent years, 15 women have died after BBLs in south Florida alone.

Melissa knew the risks. When she had her first BBL, in 2018, it happened to be the week of Leah Cambridge’s death. That same year, the British Association of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery recommended that British surgeons refrain from performing the surgery altogether. Not being a regulatory body, it couldn’t enforce a ban, though some surgeons voluntarily stopped. Still, Melissa felt safer having the operation in the UK. She trusted Glancey and, after all, she’d been through the process before – she knew what to expect. She’d have to take a few weeks off work to recover, but it would be worth it. Soon there would be no asymmetries, no dips, no flaws; she’d have a Facetuned bottom made real. A body edited. Perfection.

While the fashion holds, the perfect bottom is a taut orb, like a bauble wrapped in skin. “Sticky-outy” is Glancey’s preferred term. Working in concert with the perfect breasts, the perfect bottom turns the body into the shape of an S. “It’s the classic hourglass figure,” said Melissa. “That’s what you go after.”

The perfect bottom is also an angle: 45 degrees from the base of the spine to the top of the buttocks. In that sense, the perfect bottom is really the result of having the perfect spine, the kind that naturally protrudes at its base. According to a paper by a group of evolutionary psychologists published in the journal Evolution and Human Behaviour in 2015, “lumbar curvature” apparently signified a woman’s ability to bear children, and so made her attractive as a mate. As the authors tenderly put it: “Men tended to prefer women exhibiting cues to a degree of vertebral wedging closer to optimum.”

For those lacking the optimum degree of vertebral wedging, there are options. In the 18th century, you’d have been yanked into a corset; a little later, a bustle. Now, you can buy padded knickers or create homemade inserts. (When one of Glancey’s patients recently undressed in her clinic, two wads of rolled-up fabric fell out of her pants.) You can have implants or inject filler. Or you can have a BBL, which fulfils two briefs in one mission, removing fat from places where you don’t want it and putting it where you do. The BBL, like Robin Hood, takes from the rich – the wobbly belly – and gives to the poor: the flat, bony bum.

The BBL began in Brazil, birthplace of aesthetic surgery and the myth of the naturally “sticky-outy” bottom, the kind seen in countless tourist board images of bikini-clad women on Copacabana beach. “In the global imagination, we think Brazilians are obsessed with butts,” said the anthropologist Alvaro Jarrin, author of The Biopolitics of Beauty, which examines the culture of cosmetic surgery in Brazil. In reality, needless to say, not every Brazilian woman has the idealised Brazilian bottom. Nor, added Jarrin, does every Brazilian woman even want this kind of bottom. While researching his book, he found that the BBL’s popularity depended on the class and race of the women he was talking to. If rich and white, “they would say, ‘I don’t want the body of the ‘mulatta’ [an often derogatory term meaning biracial], I want the body of the European supermodel’.”

The surgery itself was pioneered by the Brazilian doctor Ivo Pitanguy. In a country rich in plastic surgeons, Pitanguy was known as “the pope”. He performed a variety of procedures, and was rumoured to have prettified celebrities from Frank Sinatra to Sophia Loren while offering poorer patients subsidised treatment in his Rio clinic. Beauty, Pitanguy believed, was a human right, though he recognised that its pursuit could be a troubling process. “The most important thing is to have a good ego,” Pitanguy was often quoted as saying, “and then you don’t need an operation.” A nice principle, but not the one that made him enough cash to buy himself a private island, Ilha dos Porcos Grande, or Big Pigs’ Island, off the coast of Rio.

In 1960, Pitanguy founded the world’s first plastic surgery academy, teaching his techniques to a new generation of surgeons. “He had a gift for sharing knowledge,” I was told by Dr Marcelo Daher, a leading Rio plastic surgeon who trained with Pitanguy. “And his students spread all around the world.” As surgeons learned the art of the BBL, the practice gradually travelled north. “It started to reach the southern part of North America first,” said Mark Mofid, who works in San Diego, in southern California, and has been performing BBLs for 20 years.

One of Pitanguy’s proteges was another Brazilian, Dr Raul Gonzalez, now the leading international expert on buttock enhancement. He in turn trained Glancey, who travelled to São Paulo for the experience. “That must have been at least 17 years ago,” Glancey told me. “He was the best.” She recalled how, back then in Brazil, butt lifts were “normal, whereas here it wasn’t heard of”.

Brazil remains the global centre of cosmetic surgery, in part because of Pitanguy’s legacy: free or low-cost cosmetic procedures are still available in the public health system. Not being a luxury commodity, the practice of cosmetic surgery saturates society at every level. Such accessibility has a darker side – Brazilian surgeons are “known worldwide for producing new techniques,” Jarrin told me, because “they have these low-income bodies to practise on”.

In the UK, by contrast, purely cosmetic surgery is only practised privately. Glancey’s clinic occupies a floor above an NHS GP surgery. Entering the building, then, are two very different sets of patients: those who pay and those who don’t. Glancey’s patients are making a consumer’s choice: they want something, and provided it’s possible and safe, she sells it to them. Still, Glancey insists on calling them patients rather than clients: “Yes, it’s voluntary,” she said to me, a little fiercely. “But it’s still medical, it’s still surgery.”

Sitting in her clinic on a break between patients, Glancey scrolled through Instagram messages from potential patients. “Look,” she said, as the feed of messages updated itself endlessly. “This is just the last 24 hours!” Each contained pictures the women had taken of themselves in their underwear. Glancey needs to see what she’s dealing with before she even agrees to a consultation; she can tell how successful surgery might be, or how unrealistic their desires are, simply by looking at a body.

She also requires vital statistics: age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI). “If it’s above 30 [which indicates clinical obesity], I don’t operate, I just tell them to lose weight,” she said, bluntly. “It’s liposuction, it’s not a cure for obesity.” She showed me a picture of a black woman who wanted her body turned into a “figure of 8”. Glancey shook her head: the woman was overweight, but in any case, the shape of an 8 was pushing the hourglass ideal to a physiologically impossible extreme. “You don’t need to be an expert to say to her what I’ve said to her”, Glancey told me, which was a firm and repeated, “No”.

Not everyone can achieve the Kardashian body. As with much of the Kardashian West oeuvre, her bottom has its own attendant controversies, not least because it appears to want to be an idealised version of a black woman’s bottom. Kardashian West, who has Armenian heritage and has always denied having had bottom surgery, has long been accused of “blackfishing” – mimicking and appropriating black culture to enhance her brand. “It’s completely constructed, a kind of fiction,” said Alisha Gaines, professor of English at Florida State University, and the author of Black for a Day: White Fantasies of Race and Empathy. “She’s made an empire on appropriating blackness and selling it to all types of people, including black folks.”

Aesthetic surgery has always been inseparable from the politics of race. Gaines traces the fetishisation of black women’s bottoms back to the toxic legacy of slavery and colonialism, and more specifically to the case of Saartjie Baartman, a South African woman who was brought to London in 1810 by a British doctor and exhibited in Piccadilly, and then around the country, as the “Hottentot Venus”. Crowds would pay to examine her body, and her buttocks in particular. (When Kardashian West posed for Paper magazine in 2014, a champagne glass balanced on her bottom, disconcerted observers compared the image to pictures of Baartman used to advertise her “performances”.)

In Brazil, meanwhile, the culture of cosmetic surgery emerged from the country’s history of eugenics. Dr Renato Kehl, who founded the Eugenics Society of São Paulo in 1918, expressed his support for surgery in his book The Cure of Ugliness. His aim was simple: to “perfect” Brazil’s population through “the extinction of the black and the rainforest-dwelling races”. “Beautification, for Kehl,” writes Jarrin, “was unequivocally associated with whitening.”

In its imitation of a perceived feature of blackness, rather than whiteness, the BBL might appear to go in the other direction. (Melissa told me that after her first BBL, a black friend of hers had told her how rare it was for a white girl to have a proper bum. “And I was like, ‘Yeah, so rare,” she said, pleased by her subterfuge. “But it happens.”) But the aspiration, suggested Gaines, is for a kind of cherrypicked, tokenistic black aesthetic, while retaining the societal privilege of being white. “I think what Kim Kardashian explicitly knows is that folks love black culture, and blackness, but not necessarily black people,” she added. “It’s part of a long history of white folks taking pieces of black culture, but without any of the consequences of having to be or live black.”

Glancey told me that around half of the inquiries she receives about BBLs are from black women. “They feel ugly not having the curve of the back,” she said. Following the chain of cultural appropriation that has led to this point is bewildering. The notion of the idealised Brazilian bottom, which some rich white Brazilian women disdain because of its stereotypical associations with biracial women, has become the desired shape among certain white women in the US and Europe, who are in turn emulating a body shape artificially constructed and popularised by an Armenian-American woman, who is often accused of appropriating a black aesthetic, which some black women then feel compelled to copy, not having the idealised body shape they believe they’re supposed to have naturally. “You steal a version of what a black woman’s body should be, repackage it, sell it to the masses, and then if I’m black and I don’t look like that? That’s a mindfuck,” summarised Gaines.

Glancey eventually told the woman who wanted to look like a figure 8 that even if all her fat was sucked out, she would be left with huge folds of excess skin. Finally, the woman stopped messaging. The gulf was simply too wide: not just between image and reality, but between image and possibility – the desire to look like something that wasn’t just an improved version of yourself, or an idealised version of someone else, but was out of the realm of human form, the shape of a number.

Just before Melissa’s second appointment with Glancey, a few weeks after the first, we met in a local pub, and she told me she had a new plan for her surgery. As well as having fat removed from her stomach, she also wanted Glancey to take fat from beneath her chin and her upper arms before inserting it into her bottom.

During the appointment later that afternoon, Glancey had to check whether this was possible. Sometimes patients want imagined fat removed from places where they barely have any: it’s just bone, muscle, skin.

Back in front of the full-length mirror, Glancey pinched the flesh around Melissa’s bicep. “It’s doable,” she said, cheerfully brisk, the bedside manner of a doctor with an endlessly renewing queue of eager patients.

Then she moved up to Melissa’s chin. “What bothers you here?”

Melissa made a face, as if to say, what doesn’t bother me here.

“Like, why is it here? Why is this all like this?” Melissa said, pointing to a tiny cushion of fat beneath her jaw-line. (Glancey described it as “a little bit of natural padding”.)

Glancey said she would remove the fat manually, with a syringe, and probably wouldn’t get more than 20 cubic cm out. She reminded Melissa that she would have to wear a compression bandage beneath her chin, as well as a garment around her stomach and bottom after the operation, to aid healing. Recovering from a BBL is painful. Melissa told me that she hadn’t felt much discomfort in her bottom in the weeks immediately after her first BBL, because it was cushioned by the new fat, but the areas where she had liposuction had been so sensitive that when someone brushed past her a few weeks after the operation, she cried out in pain.

For the operation itself, scheduled for a few weeks’ time, Glancey would follow her usual process. First, she marks up the patient with a pen – black ink for where she’s removing fat, red for where it’s going back in. She does this with the patient and takes photos, so there’s no post-operative dispute about what was planned. Then the patient is anaesthetised, and a saline solution including local anaesthetic and adrenaline is pumped through their body to help shrink the blood vessels, control the bleeding, and to create a “wetting” effect so the fat can be removed more easily. Without it, Glancey said, liposuction would be a bit like trying to scrape dried food off a plate without any water.

Glancey then makes another small incision and inserts a blunt cannula under the skin to “harvest” the fat. As the fat is sucked out of the body, it travels down a plastic tube to a closed canister where it is washed of blood and local anaesthetic. Once removed, the fat only survives for an hour or two. It’s still “alive” – fat is often described as an “endocrine organ” because of its ability to secrete hormones – and can change colour in front of your eyes, starting a sort of yellowy or orange hue, if it’s mixed with blood, before gradually turning brown. (“Not a good sign,” said Glancey.)

For the fat to stand the greatest chance of survival in the body, it has to be quickly inserted back into the buttocks, once again using a blunt cannula and aided by a foot-controlled pump. Here, the surgeon becomes a kind of combination of a blind sculptor and one of those musicians who can play multiple instruments simultaneously by strapping them to different parts of their body. While the foot controls the pace of the fat coming back up into the body, Glancey’s right hand guides the cannula, and her left hand – which she calls the “seeing hand” – strokes the surface of the skin to feel where the fat should be placed. “It’s not an open wound,” she said. “You can’t see anything.”

In a series of videos Glancey sent me of her performing the procedure, the sheer vigour required was striking. She pumped the cannula forwards and backwards repeatedly, like a particularly involved handheld vacuum cleaning session. An operation can last anywhere between three to six hours, and the thrusting motion is necessary for fat removal and insertion. By the end, Glancey is often exhausted. The patient’s body, meanwhile, like any anaesthetised body undergoing a serious operation, resembled a lifeless slab of flesh, which Glancey handled with that odd surgical balance of delicacy and force.

A patient has to wait weeks before they know what their bottom will ultimately look like. The fat takes time to settle, and Glancey has to remind her patients that at best, only about 50% of the fat “takes”. The rest is absorbed by the body and ejected through the lymphatic system. To optimise the amount of fat that survives in the body requires a surgeon’s skill. Glancey compares it to creating a garden: you can’t put plants too close together, they need space to thrive. “When I say this to patients, they just say put more in,” she said. “And I say, well, it doesn’t work like that.” Glancey sticks to the UK guidelines and limits how much she will insert – 300cc per buttock, a little less than a can of Coke. She tells her patients to complete the BBL over more than one operation, adding a little at a time.

In Turkey, the most popular destination for cosmetic surgery patients travelling abroad in Europe – and the third most popular in the world, after Thailand and Mexico – the limits are less conservative. Some surgeons openly advertise on social media that they will insert more than 1,000cc into a patient’s buttocks. Glancey says that she regularly sees patients who have returned from Turkey unhappy with the results, often because a significant quantity of fat has died and left them lopsided or misshapen.

The risk involved in performing a BBL is not only about the quantity of fat, but how it is inserted. (Also, whether it is fat being inserted at all: a number of recent deaths associated with buttock augmentation occurred because the patient was being injected with silicone.) During the operation, the danger occurs at a very precise moment: the insertion of the cannula into the buttock. As it goes under the skin, the cannula has to remain above the gluteal muscle. If it goes below, and fat enters the bloodstream, fat droplets can then coalesce, travel through the blood and cause a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in the lungs – the cause of death in the case of the British woman, Leah Cambridge, who had a BBL at a private clinic in Izmir in 2018.

On her phone, Melissa showed me pictures of women on Instagram she knew who’d had BBLs at Turkish clinics, pointing out telltale signs like an art dealer spotting fakes. The belly button, for example. When so much fat is taken from the waist, the belly button can end up distorted, said Melissa. The proportions also tend to be more extreme, the waist carved inwards and buttocks inflated to cartoonish proportions.

“It just doesn’t look human,” said Melissa, pointing to a woman whose belly button looked like it had been steamrolled, then stretched. Melissa shook her head knowingly. “That’s badly done,” she said. “And there are so many girls like this.”

One of the most popular Turkish clinics, which advertises its £3,000 BBL package heavily on Instagram, is called Comfort Zone. Its timeline is a carnival of teeth, breasts, noses and bottoms, with more intimate body parts – nipples, anuses – tastefully covered with a star-shaped “CZ” logo. Visit the Comfort Zone website and cosmetic surgery appears to resemble a spa retreat. There are photographs of villas and pools, and happy-looking people sitting round a breakfast table laden with tropical fruits arranged in the shape of flowers. Mysteriously, there are also images of empty meeting rooms, perhaps to signal that executive professionalism happens here, just not at the moment the picture was taken.

Comfort Zone was founded 10 years ago by British-Turkish businessman Engin Yesilirmak, who previously ran a freight transportation company. Yesilirmak told me he had the idea for his new venture when he arranged cosmetic surgery in Istanbul for friends and family and realised that it was easy to do and much cheaper than the UK: an ideal business model. Surgeons at Comfort Zone now perform 200 surgeries a month, and the company houses 40 patients at any one time in its five “recovery villas”.

Comfort Zone offers everything – rhinoplasty, BBL, breast implants, contouring and the “mommy makeover”, a surgery that aims to correct the aesthetic ruin of reproduction. Yesilirmak suggested that women were drawn to Comfort Zone not just by their cheap BBL package but because of the freedom a Turkish surgeon enjoys. “The doctors are braver here than in Europe,” said Yesilirmak. “Here we will take four litres of fat.” In some of the clinic’s Instagram posts, they proudly state the precise quantities of fat next to images of a transformed body: “4200 cc removed 1200cc in.”

Also “brave”, according to Yesilirmak, were the young women who regularly visit his clinic alone. Yesilirmak, perhaps aware of the many tales of women returning from Turkey with complications, was keen to emphasise that, as with any surgery, there were risks. “It’s the law of averages,” he told me. In Yesilirmak’s estimate, 2% of surgeries at Comfort Zone involve minor complications (an improvement on 3% last year), but they’d never had a major incident. If something does go wrong, he said, they offer a free “revision” after three months. (There are at least two Instagram accounts that claim to document botched surgeries carried out at Comfort Zone. “Unfortunately, some patients, instead of coming back for revision surgery, start a campaign of hate,” said Yesilirmak.) He also maintained that they were honest with women who they felt they couldn’t help. “Like if they’re really overweight and want to become really tiny in one go,” he said. “It’s just not possible.”

Yesilirmak wasn’t forcing anyone to have surgery, he said. Comfort Zone simply advertises its services, and it’s up to the clients if they come or not. “We never do a hard sell,” he told me. Its marketing mostly takes place through Instagram personalities such as the model Holly Deacon, the one-time X Factor contestant turned cosmetically transformed influencer Chloe Khan and the enduring reality veteran Katie Price. Occasionally they’ll throw in the odd gimmick. Recently, to celebrate reaching 100,000 Instagram followers, Comfort Zone invited its fans to leave a comment on a post and tag five friends. It would then select a winner and give them a free surgery of their choice, hopefully having multiplied their followers along the way. (“The irresponsible marketing, the glamorisation, the trivialisation, the incentivisation,” said Mary O’Brien, president of the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. “These are all things that our organisation is trying to highlight as areas of concern.”)

“The giveaways are not so effective,” said Yesilirmak. The best strategy was always influencer promotion: that’s how you attract new clients, such as Katrina Harrison, who told the Mirror in 2019 how she’d gone to Comfort Zone for a BBL having seen Katie Price promoting the clinic. Harrison claimed she almost died from sepsis after her surgery. When she returned to the UK, Harrison reportedly collapsed at Manchester airport, and was admitted to hospital for nine days. (Yesilirmak said her claims were “totally fabricated”. Nonetheless, as a result of similar cases, the Turkish ministry of health introduced a stricter accreditation process for Turkish medical tourism companies in 2018.)

In late 2019, after her latest round of operations, Price made a promotional video for the company, which included a scene of her in the back of a limo rapping along to 50 Cent’s In Da Club with her own lyrics: “Comfort Zone, it’s where you wanna be! Smaller boobs and my eyelids!” Sitting in a lush garden, she declared that her recent surgeries were the start of a process in which she was going to gradually morph into a “human doll”. “Comfort Zone have said they’re going to give me the perfect body,” said Price, with a certain zeal. “But it takes time, you can’t have it all done at once. This is just the beginning!”

Beauty has always been a matter of cruel chance: you’re born that way. We all perform appearance-enhancing tricks that we’d haughtily never place in the same category as cosmetic surgery – teeth-straightening, eyebrow-threading, Spanx. Recently, I found myself staring into the mirror, wondering how much it would cost to laser into oblivion a constellation of brown sunspots on my cheek. (Too much.) Wrestling nature can be a life’s expensive work, and so perhaps the cheapening and therefore democratising of cosmetic surgery is a middle finger up to evolution. We can all be beautiful now, and reap the associated aesthetic and financial rewards.

The commercial effects of a BBL are straightforward: “It brings you more work,” said Glancey to Melissa, back in the clinic. “And more money,” agreed Melissa. Her BBL body triumphs in the algorithmic beauty pageant: she gets more likes, and the likes win her more gigs.

“It’s an investment,” said Glancey. “It’s like, if I build a new [operating] theatre, I’m investing in my business … It should be tax deductible!” (Melissa charges £50 for an Instagram post and gets a lot of free clothes: the £8,000 investment will take a while to recoup.)

Another of Glancey’s clients, called Jema, told me that since she’d had her first BBL, her job as a glamour model had become significantly easier. An old-timer in the trade, Jema used to appear regularly in the Sunday Sport, then segued to social media, and now mostly operates on OnlyFans, a vastly successful online platform dominated by glamour models and porn actors who share content privately with paying subscribers. She used to have to strip or rub cream in her breasts for her fans, and now all she has to do is wear a vest and a pair of shorts and jiggle her new bottom in front of a camera.

Jema calculated she was earning £5,000-£6,000 a month on OnlyFans: good money, though not as much as her porn-star friends who earn up to £15,000 every month on the platform. And not as much as the cash being made off the back of these women’s bodies by OnlyFans founder Tim Stokely or its majority stakeholder, the porn entrepreneur Leonid Radvinsky. (Estimates have put the platform’s annual net sales at $400m.)

After her second BBL, and all the benefits it would bring, Melissa liked to think she’d be content. But once you start having surgery, she told me, it can be hard to stop. She finds herself on surgery websites, browsing. “I’m in love with the ski-slope nose now,” she said. “Like, where did that come from?”

Melissa was mystified by her own desire, but it came to her the way desires usually do: you see something you like, and you want it for yourself. Surgery can change the way you see your body. No longer is it a gradually decaying biological event, but a project that can be constantly improved, like a kitchen. The problem is, what happens when you’ve built the perfect kitchen, which is blue, and then everyone decides that the perfect kitchen should actually be red?

“When someone requests extremely large buttocks,” Glancey told me on the phone one evening, “I always explain to them that fashions could change.” She tells them to opt for a more conservative look, otherwise when the coveted body shape does inevitably switch again, they’ll just need more surgery.

In any case, no matter how much work you do to it, the body remains alive, organic, unpredictable. Even the Kardashian West bottom might not for ever look as it does today, swathed as it was recently in a dress printed with an image of Kardashian West’s own face (2.1m likes). However hard we try, no one can inhibit nature entirely. Gravity and time will have their way with an ageing BBL, as they do with everything else. Even the perfect bottom will sag; even the perfect body will die.

• Melissa’s name has been changed.

____________________________________________________

Sophie Elmirst is a contributing editor to Harper’s Bazaar and writes regularly on books for the Financial Times. She lives in London.

Go to Original – theguardian.com

Tags: Emotional Health, Fashion industry, Health, Mental Health, Modernity, Public Health

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.